Aftermath of the Cuban Revolution

During its first decade in power, the Castro government introduced a wide range of progressive social reforms. Laws were introduced to provide equality for black Cubans and greater rights for women, and there were attempts to improve communications, medical facilities, health, housing, and education. In addition, there were touring cinemas, art exhibitions, concerts, and theatres. By the end of the 1960s, all Cuban children were receiving some education (compared with less than half before 1959), unemployment and corruption were reduced, and great improvements were made in hygiene and sanitation.[1] Fidel dedicated many of his years to the equality among Afro-Cubans and the wealthy white people of Cuba. His anti-discrimination legislation was his first and major attempt to give equality to the people of Cuba. His many reforms (healthcare, education, and equality) gave opportunities to those Afro-Cubans who lived in poverty because of the racial discrimination in Cuba.[2]

The equal right of all citizens to health, education, work, food, security, culture, science, and wellbeing – that is, the same rights we proclaimed when we began our struggle, in addition to those which emerge from our dreams of justice and equality for all inhabitants of our world – is what I wish for all.

— Fidel Castro[3]

| Part of the Cold War | |

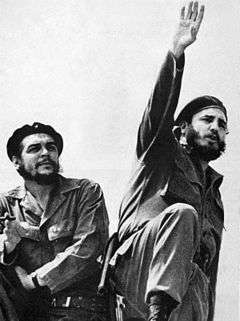

Che Guevara (left) and Fidel Castro (right) in 1961. | |

| Date | 1960s |

|---|---|

| Location | Cuba |

| Outcome | Series of events including... |

Background

The Cuban Revolution (Spanish: Revolución cubana) was a guerrilla campaign by Fidel Castro's revolutionary 26th of July Movement and others against the dictatorship of Cuban President Fulgencio Batista. The revolution started in July 1953,[4] and continued to varying degrees until the rebels finally ousted Batista on 31 December 1958, creating a new revolutionary government.[5]

After learning of Batista's flight the rebels immediately started negotiations to take over Santiago de Cuba. On 2 January, Cuban Colonel Rubido, ordered his soldiers to stand down, and the rebels took the city. The rebel forces under Guevara and Cienfuegos entered Havana at about the same time. The rebels met no opposition on their way from Santa Clara to Havana. Castro arrived in Havana on 8 January after a victory march. His first choice of president, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, took office on 3 January.[6]

1959: Rebel victory

Our revolution is endangering all American possessions in Latin America. We are telling these countries to make their own revolution.

— Che Guevara, October 1962[7]

Events after victory

On 11 January 1959 Ed Sullivan would interview Fidel Castro in Matanzas and broadcast it on The Ed Sullivan Show. In the interview Ed Sullivan refers to the Castro and other rebels as "a wonderful group of revolutionary youngsters" and point out their admiration for Catholicism. Fidel Castro would deny the rebels affiliation with communism. Hours after the interview Fidel Castro would ride on captured tanks into the capital in Havana.[8]

Revolutionary tribunals

Hundreds of Batista-era agents, policemen and soldiers were put on public trial, accused of human rights abuses, war crimes, murder, and torture. About 200 of the accused people were convicted of political crimes by revolutionary tribunals and then executed by firing squad; others received long sentences of imprisonment. A notable example of revolutionary justice occurred after the capture of Santiago, where Raúl Castro directed the execution of more than seventy Batista POWs.[9] For his part in taking Havana, Che Guevara was appointed supreme prosecutor in La Cabaña Fortress. This was part of a large-scale attempt by Fidel Castro to cleanse the security forces of Batista loyalists and potential non-Communist opponents (including high-ranking rebels such as Pedro Luis Díaz Lanz and Huber Matos) of the new revolutionary government. Though many were killed or imprisoned, others were dismissed from the army and police without prosecution, and some high-ranking officials of the Batista administration were exiled as military attachés.[9] It is widely believed that those executed were guilty of the crimes of which they were accused, but that the trials did not follow due process.[10]

Racial integration campaign

Starting in March 1959 Fidel Castro announced in a speech he would attempt to end racial discrimination in Cuban society. He detailed a plan to bring black and white Cubans together in shared schools and other institutions, via equal opportunity. In a later televised discussion Castro claimed his plans were mostly to improve economic conditions for black Cubans and that he is not encouraging total social integration. Social clubs were to be totally integrated, private beaches opened, and schools totally nationalized. Revolutionary leaders would also decry to the white supremacist terrorism of the U.S. South in an attempt to gain a moral high ground and defame Cuban exiles living in the United States.

Private schools that once had majority white student bodies were now nationalized and faced an influx of new black and mulatto students. Social clubs were told to integrate as early as January 1959. White and black social clubs began to dissolve. Racism became branded as counterrevolutionary and critics of the government were often branded as racists.[11]

Some white Cubans were fearful of integration, while some black Cubans were fearful of the closing of black social clubs and its affects on Afro-Cuban cultural life.[11]

Diplomatic visit to the United States

On 15 April 1959, Castro began an 11-day visit to the United States, at the invitation of the American Society of Newspaper Editors.[12] Fidel Castro made the visit in hopes of securing U.S. aid for Cuba. While there he openly spoke of plans to nationalize Cuban lands and at the United Nations he declared Cuba was neutral in the Cold War.[13] He said during his visit: "I know the world thinks of us, we are Communists, and of course I have said very clear that we are not Communists; very clear."[14]

Land reform

According to geographer and Cuban Comandante Antonio Núñez Jiménez, 75% of Cuba's best arable land was owned by foreign individuals or foreign (mostly American) companies at the time of the revolution. One of the first policies of the newly formed Cuban government was eliminating illiteracy and implementing land reforms. Land reform efforts helped to raise living standards by subdividing larger holdings into cooperatives. Comandante Sori Marin, who was nominally in charge of land reform, objected and fled, but was eventually executed when he returned to Cuba with arms and explosives, intending to overthrow the Castro government.[15][16]

In March 1959, Castro had already ordered rents for those who paid less than $100 a month to be halved. Productivity in the country would later decreased, and the country's financial reserves were drained within only two years.[17]

After appointing himself president of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agraria – INRA), on 17 May 1959, Castro made law the First Agrarian Reform, limiting landholdings to 993 acres (4.02 km2) per owner. Cuba would also forbid further foreign land-ownership. Large land-holdings were broken up and redistributed; an estimated 200,000 peasants received title deeds. To Castro, this was an important step that broke the control of the well-off landowning class over Cuba's agriculture. Though popular among the working class, it alienated many middle-class supporters.[18]

Although Castro refused to initially categorize his government as 'socialist' and repeatedly denied specifically being a 'communist', Castro appointed advocates of Marxism-Leninism to senior government and military positions. Most notably, Che Guevara became Governor of the Central Bank and then Minister of Industries. Appalled, Air Force commander Pedro Luis Díaz Lanz defected to the U.S.[19]

1960: Developments in Cuba

Censorship

Journalists and editors began to criticize Castro's left-ward turn, the pro-Castro printers' trade union began to harass and disrupt press actions. In January 1960, the government proclaimed that each newspaper need to publish a "clarification" by the printers' union at the end of every article that criticized the government. These "clarifications" signaled the start of press censorship in Castro's Cuba.[20][21]

La Coubre explosion

Cuba-United States relations were heavily strained after the explosion of a French vessel, the La Coubre, in Havana harbor in March 1960. The ship carried weapons purchased from Belgium, and the cause of the explosion was never determined, but Castro publicly insinuated that the U.S. government was guilty of sabotage. He ended this speech with "¡Patria o Muerte!" ("Fatherland or Death"), a proclamation that he made much use of in ensuing years.[22]

The United States was already suspicious of Fidel Castro after he enacted the Agrarian Reform Law banning foreigners from owning land and his appointment of communist Nuñez Jimenez as head of the reform program. U.S. President Eisenhower refused any aggressive action against Cuba knowing it would push Cuba towards an alliance with the Soviet Union in the Cold War.[13]

Castro's visit to New York City

Fidel Castro made a trip to New York City starting September 18 to attend the United Nations general assembly. While there international tensions were much higher than during his 1959 trip and he was restricted to only staying on Manhattan island. Castro checked in to the Shelbourne Hotel then checking out a few hours later, complaining that the Shelbourne had asked for a $10,000 cash advance. Castro would then threaten the United Nations that he would camp in Central Park if he couldn't find lodging, eventually checking into the Hotel Theresa in Harlem. While there Castro would meet with various interviewers with African-American newspapers, and other notable people such as Malcolm X, Langston Hughes, Nikita Khrushchev and Allen Ginsberg. During his stay various Castro supporters and opponents would crowd the outside of the hotel, often fighting. Various sensationalist stories came out about Castro at the time, rumors claimed his entourage were harboring prostitutes in the hotel and that Castro was originally kicked out of the Shelbourne for keeping live chickens in the room. By September 26 Castro would finally speak at the U.N. and would speak for over four hours in denouncing United States foreign policy. Two days later Castro would return to Cuba in a soviet jet, after his jets were repossessed at the airport.[23]

Foundation of CDRs

Shortly after taking power, Castro also founded a revolutionary militia to expand his power base among the former rebels and the supportive population. Castro also founded the informant Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) in late September 1960. Local CDRs were tasked with keeping "vigilance against counter-revolutionary activity", keeping a detailed record of each neighborhood's inhabitants' spending habits, level of contact with foreigners, work and education history, and any "suspicious" behavior.[24] Among the increasingly persecuted groups were homosexual men.[25]

United States embargo and nationalizations

On 13 October 1960, the US government then prohibited the majority of exports to Cuba – the exceptions being medicines and certain foodstuffs – marking the start of an economic embargo. In retaliation, the Cuban National Institute for Agrarian Reform took control of 383 private-run businesses on 14 October, and on 25 October a further 166 US companies operating in Cuba had their premises seized and nationalized, including Coca-Cola and Sears Roebuck.[26][27] On 16 December, the US then ended its import quota of Cuban sugar.[28]

By the end of 1960, the revolutionary government had nationalized more than $25 billion worth of private property owned by Cubans.[29] The Castro government formally nationalized all foreign-owned property, particularly American holdings, in the nation on 6 August 1960.[30]

1961: Continuing tensions

Bay of Pigs Invasion

In January 1961, Castro ordered Havana's U.S. Embassy to reduce its 300 staff, suspecting many to be spies. The U.S. responded by ending diplomatic relations, and increasing CIA funding for exiled dissidents; these militants began attacking ships trading with Cuba, and bombed factories, shops, and sugar mills.[31] Both Eisenhower and his successor John F. Kennedy supported a CIA plan to aid a dissident militia, the Democratic Revolutionary Front, to invade Cuba and overthrow Castro; the plan resulted in the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961. On 15 April, CIA-supplied B-26's bombed three Cuban military airfields; the U.S. announced that the perpetrators were defecting Cuban air force pilots, but Castro exposed these claims as false flag misinformation.[32] Fearing invasion, he ordered the arrest of between 20,000 and 100,000 suspected counter-revolutionaries,[33] publicly proclaiming that "What the imperialists cannot forgive us, is that we have made a Socialist revolution under their noses". This was his first announcement that the government was socialist.[34]

The CIA and Democratic Revolutionary Front had based a 1,400-strong army, Brigade 2506, in Nicaragua. At night, Brigade 2506 landed along Cuba's Bay of Pigs, and engaged in a firefight with a local revolutionary militia. Castro ordered Captain José Ramón Fernández to launch the counter-offensive, before taking personal control himself. After bombing the invader's ships and bringing in reinforcements, Castro forced the Brigade's surrender on 20 April.[35] He ordered the 1189 captured rebels to be interrogated by a panel of journalists on live television, personally taking over questioning on 25 April. 14 were put on trial for crimes allegedly committed before the revolution, while the others were returned to the U.S. in exchange for medicine and food valued at U.S. $25 million.[36] Castro's victory was a powerful symbol across Latin America, but it also increased internal opposition primarily among the middle-class Cubans who had been detained in the run-up to the invasion. Although most were freed within a few days, many left Cuba for the United States and established themselves in Florida.[37]

Education reforms

In 1961, the Cuban government nationalized all property held by religious organizations, including the dominant Roman Catholic Church. Hundreds of members of the church, including a bishop, were permanently expelled from the nation, as the new Cuban government declared itself officially atheist. Education also saw significant changes – private schools were banned and the progressively socialist state assumed greater responsibility for children.[38]

Mafia expropriations

The Cuban government also began to expropriate from mafia leaders and taking millions in cash. Before Meyer Lansky fled Cuba, he was said to be worth an estimated $20M ($163,685,121 in 2016, accounting for inflation). When he died in 1983, his family was shocked to find out that his estate was worth about $57,000. Before he died, Lansky said that Cuba "ruined" him.[39]

Political solidification

In July 1961, the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (IRO) was formed by the merger of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement, the People's Socialist Party led by Blas Roca, and the Revolutionary Directorate of 13 March led by Faure Chomón.[40] On 26 March 1962, the IRO became the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution (PURSC) which, in turn, became the modern Communist Party of Cuba on 3 October 1965, with Castro as First Secretary. Castro remained the ruler of Cuba, first as Prime Minister and, from 1976, as President, until his retirement on February 20, 2008.[41] His brother Raúl officially replaced him as president later that same month.[42]

Effects

Opposition to Fidel Castro

In the wake of the revolution, thousands of disaffected anti-Batista rebels, former Batista supporters, and campesinos (peasants) fled to Cuba's Las Villas province, where an anticommunist underground had been forming since early 1960. Operating out of the Escambray Mountains, these counterrevolutionary rebels, also known as Alzados, made a number of unsuccessful attempts to overthrow the Cuban government, including the abortive, United States-backed Bay of Pigs Invasion of 1961.[43]

Luis Posada and CORU are widely considered responsible for the 1976 bombing of a Cuban airliner that killed 73 people.[44][45]

In January 1961 the U.S. cut off diplomatic relations with Cuba. The U.S. feared Soviet influence in Cuba and backed the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion of April 1961. By December 1961 Fidel Castro for the first time openly expressed his communist sympathies. Castro's fears of another invasion and his new Soviet allies influenced his decision to put nuclear missiles in Cuba, triggering the Cuban Missile Crisis.[13]

In the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, the United States promised not to invade Cuba in the future; in compliance with this agreement, the U.S. withdrew all support from the Alzados, effectively crippling the resource-starved resistance.[46] The counterrevolutionary conflict, known abroad as the Escambray Rebellion, lasted until about 1965, and has since been branded the War Against the Bandits by the Cuban government.[46]

Luis Posada and CORU are widely considered responsible for the 1976 bombing of a Cuban airliner that killed 73 people.[44][45]

Cuban exile

Between 1959 and 1980, an estimated 500,000 Cubans left the island for the United States, for both political and economic reasons; 125,000 left in 1980 alone, when the Cuban government briefly permitted any Cubans who wished to leave to do so.[47] By 2010, the Cuban American community numbered over 1.9 million, 67% of whom lived in the state of Florida.[48] As a voting bloc, Cuban Americans have traditionally been strongly opposed to ending the U.S. embargo of Cuba, but in recent years there has been growing support for diplomatic engagement among the younger generations.[49]

New racial policies

Castro's government was entirely based on his ideologies of equality and fair measures for the people of Cuba. After he considered to have done everything in his power toward equality, he passed a legislation that counter-attacked his past anti-discrimination legislation. This law made it illegal to even mention discrimination or the topic of equality.[2]

References

- Mastering Modern World History by Norman Lowe, second edition.

- Espina, Rodrigo (March 2006). "Raza y desigualdad en Cuba actual" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2017.

- "Fidel Castro Quotes".

- Faria, Miguel A., Jr. (27 July 2004). "Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement". Newsmax Media. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Cuba Marks 50 Years Since 'Triumphant Revolution'" Archived 27 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Jason Beaubien. NPR. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- Thomas (1998), pp. 691–93

- "Attack us at your Peril, Cocky Cuba Warns US" Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Henry Brandon. The Sunday Times. 28 October 1962. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "When Fidel Castro Charmed the United States". Smithsonian.com.

- Clark (1992), pp. 53–70

- Chase, Michelle (2010). "The Trials". In Greg Grandin; Joseph Gilbert (eds.). A Century of Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 163–98. ISBN 978-0822347378. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- Benson, Devyn (2012). "Owning the Revolution: Race, Revolution, and Politics from Havana to Miami, 1959–1963" (PDF).

- Glass, Andrew (15 April 2013). "Fidel Castro visits the U.S., April 15, 1959". Politico. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Stanley, John. "What impact did the Cuban Revolution have on the Cold War?" (PDF).

- "Cuban Revolution". 1959 Year in Review. United Press International. 1959. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Font (1995), pp. 80–81

- Lazo (1968), pp. 288

- Bourne 1986, p. 186.

- Bourne 1986, pp. 177–178; Quirk 1993, p. 280; Coltman 2003, pp. 159–160, "First Agrarian Reform Law (1959)". Retrieved August 29, 2006..

- Bourne 1986, pp. 176–177; Quirk 1993, p. 248; Coltman 2003, pp. 161–166.

- Bourne 1986. p. 197.

- Coltman 2003. pp. 165–66.

- Bourne 1986, pp. 201–202

- Andrews, Evan (August 31, 2018). "Fidel Castro's Wild New York Visit". History.com.

- Clark (1992), pp. 131–158

- Young, Allen (1982). Gays under the Cuban revolution. Grey Fox Press. ISBN 0-912516-61-5.

- Bourne 1986. p. 214.

- Coltman 2003. p. 177.

- Bourne 1986. p. 215.

- Lazo, Mario (1970). American Policy Failures in Cuba – Dagger in the Heart. Twin Circle Publishing Co.: New York. pp. 198–200, 204. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 68-31632.

- Gary B. Nash, Julie Roy Jeffrey, John R. Howe, Peter J. Frederick, Allen F. Davis, Allan M. Winkler, Charlene Mires and Carla Gardina Pestana. The American People, Concise Edition: Creating a Nation and a Society, Combined Volume (6th edition, 2007). New York: Longman.

- Bourne 1986, pp. 215–216; Quirk 1993, pp. 353–354, 365–366; Coltman 2003, p. 178.

- Bourne 1986, pp. 217–220; Quirk 1993, pp. 363–367; Coltman 2003, pp. 178–179.

- Bourne 1986, pp. 221–222; Quirk 1993, p. 371.

- Bourne 1986, pp. 221–222; Quirk 1993, p. 369; Coltman 2003, pp. 180, 186.

- Bourne 1986, pp. 222–225; Quirk 1993, pp. 370–374; Coltman 2003, pp. 180–184.

- Bourne 1986, pp. 226–227; Quirk 1993, pp. 375–378; Coltman 2003, pp. 180–184.

- Coltman 2003, pp. 185–186.

- Faria (2002), pp. 215–28

- "Fidel Castro a mixed legacy that includes fighting the mafia". 26 November 2016. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Kantor, Myles B. (14 June 2002). "Interview With Dr. Miguel Faria (Part I)". Newsmax Media. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Fidel Castro Resigns as Cuba's President". New York Times. 20 February 2008. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Raúl Castro becomes Cuban president". New York Times. 24 February 2008. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Ahead Of Bay Of Pigs, Fears Of Communism". NPR. 17 April 2011. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- Bardach, Ann Louis; Rohter, Larry (July 13, 1998). "A Bomber's Tale: Decades of Intrigue" Archived 3 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. The New York Times Company.

- Lettieri, Mike (June 1, 2007). "Posada Carriles, Bush's Child of Scorn". Washington Report on the Hemisphere. 27 (7/8).

- "Cuba: Intelligence and the Bay of Pigs". Stanford University. 26 September 2002. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Cuban Exile Community". LatinAmericanStudies.org. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "Hispanics of Cuban Origin in the United States, 2010". Pew Research. 27 June 2012. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "Latino millennials want to end Cuba embargo". CNN. 24 October 2012. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

Sources

- Bourne, Peter G. (1986). Fidel: A Biography of Fidel Castro. New York City: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 978-0-396-08518-8.