South Yemen Civil War

The South Yemeni Civil War, colloquially referred to as The Events of '86 or The Events of January 13, or more simply as The Events, was a failed coup d'etat and armed conflict which took place on January 13, 1986 in South Yemen. The civil war developed as a result of ideological differences, and later tribal tensions, between two factions of the ruling Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP), centred on Abdul Fattah Ismail's faction, al-Toghmah, and Ali Nasir Muhammad's faction, al-Zomrah, for the leadership of the YSP and the PDRY. The conflict quickly escalated into a costly civil war that lasted eleven days and resulted in thousands of casualties. Additionally, the conflict resulted in the demise of much of the Yemeni Socialist Party's most experienced socialist leadership cadre, contributing to a much weaker government and the country's eventual unification with North Yemen in 1990.

| South Yemeni Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Cold War | |||||||

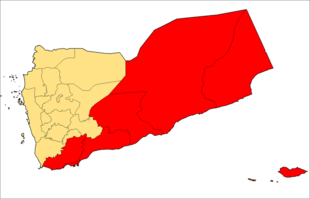

Governorates which previously formed the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen in red | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Mobilized tribal militias |

Mobilized tribal militias | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

4,000 – 10,000 dead[1] 60,000 refugees | |||||||

Background

Following the end of the Aden Emergency and the achievement of South Yemeni independence in 1967, the National Liberation Front (NLF) was handed power over the country following negotiations with the British government in Geneva. A broadly left-wing nationalist insurgent organization, the NLF had sought to unite the forces of the Aden petroleum and port workers' trade unions, Nasserites, and Communists. The last of these factions was led by Abdul Fattah Ismail, a founding member of the NLF and its chief Marxist ideologue. During the Emergency, Ismail had led the armed cadres of the NLF in Aden, and was supported by many of the insurgents who had seen action against the British. In 1969, with support from the Soviet Union, Ismail used this popularity among the nascent South Yemeni army to seize control of the NLF, and in June he was declared its General Secretary.

Ismail pursued aggressive and revolutionary domestic and foreign policies. At home, the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen adopted a Marxist-Leninist scientific socialism as the official state ideology. All major industries were nationalized and collectivized, universal suffrage was implemented, and a quasi-cult of personality was developed around Ismail and the NLF, renamed the Yemeni Socialist Party in 1978. His government helped establish Marxist paramilitary organizations around the Arabian Peninsula, PFLOAG and PFLO, which used political activism and violence to campaign against the Western-aligned Arab monarchies on the Persian Gulf. Under Ismail, South Yemen gave its most direct support to the later of these two groups during the Dhofar Rebellion in neighbouring Oman, providing advisors to the insurgent forces there, in addition to ensuring the transit of Warsaw Pact and Chinese weapons to the rebels. He also encouraged Communist guerrillas in North Yemen, seeking to destabilize the regime of Ali Abdullah Saleh and bring about Yemeni unification under a Communist government based in the South. This antagonism toward the North would stoke tensions between the two Yemens, eventually culminating in a brief series of border skirmishes in 1972.

Following the failure of the insurgency in Oman in 1978 and simmering hostilities with North Yemen, Ismail had lost favour with much of the Yemeni Socialist Party's rank and file and alienated his country from much of the region and the West. This, combined with Ismail's economic policies had devastated the small nation's hitherto low standard of living. The Soviet Union, upon which South Yemen relied for the vast majority of its trade and financial aid, had also lost confidence in the General Secretary, policymakers within the Brezhnev administration regarding him as a loose cannon and a liability. As a result, Moscow began to encourage moderates within the YSP to remove him from power. In 1980, believing that his political rivals within the YSP were preparing to assassinate him, Ismail resigned and went into exile. His successor, Ali Nasir Muhammad, took a less interventionist stance toward both North Yemen and neighbouring Oman. The Yemeni Socialist Party was increasingly polarised between Ismail's supporters, who espoused a hard-line leftist ideology, and those of Ali Nasir Muhammad who espoused more pragmatic domestic policies and friendlier relations with other Arab states and the West.

In June 1985, the YSP politburo adopted a resolution stating that anyone who resorted to violence in settling internal political disputes is considered a criminal and a betrayer of the homeland.[2]

War

On January 13, 1986, bodyguards of Ali Nasir Muhammad opened fire on members of the Yemeni Socialist Party politburo as the body was due to meet. As most of the politburo members were armed and had their own bodyguards, a firefight broke out. Ali Nasir's supporters were not in the meeting room at the time. Vice-president Ali Ahmad Nasir Antar, Defense minister Saleh Muslih Qassem and the YSP disciplinary chief Ali Shayi' Hadi were killed in the shootout. Abdul Fattah Ismail survived the attack but was apparently killed later on that day as naval forces loyal to Ali Nasir shelled the city.[2][3]

Fighting lasted for 12 days and resulted in thousands of casualties, the ouster of Ali Nasir's, and the deaths of Abdul Fattah Ismail, Ali Antar, Saleh Muslih, and Ali Shayi'. Some 60,000 people, including Ali Nasir and his brigade, fled to the YAR. In the conflict that took the lives of anywhere from 4,000 to 10,000 people, al-Beidh was one of the few high-ranking officials of Abdul Fattah's faction on the winning side who survived.[1]

Succession

A former Politburo member, al-Beidh took the top position in the YSP following a 12-day 1986 civil war between forces loyal to former chairman Abdul Fattah Ismail and then-chairman Ali Nasir Muhammad. An Ismail ally, he took control after Mohammad's defeat and defection, and Ismail's death.[4][5]

Aftermath

Unification of Yemen and 1994 civil war

Suffering a loss of more than half its aid from the Soviet Union from 1986 to 1989,[6] and an interest in possible oil reserves on the border between the countries, al-Beidh's government worked toward unification with North Yemen officials.[7][8]

Efforts toward unification proceeded from 1988. Although the governments of the PDRY and the YAR declared that they approved a future union in 1972, little progress was made toward unification, and relations were often strained.

In 1990, North Yemen and South Yemen united into one country, but in February 1994, clashes between northern and southern forces started and quickly developed into a full-scale civil war. As northern forces advanced on Aden, al-Beidh declared the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Yemen on 21 May.[9] The southern resistance however failed. Saleh enlisted Salafi and Jihadist forces to fight against Southern forces of the Yemeni Socialist Party. Forces loyal to Ali Nasir also took part. Northern forces entered Aden on 7 July.

Southern Movement

In 2007 southern army officers and security officials who had been forced into retirement after the 1994 war started demonstrations calling for their reinstatement or compensation. The protests gradually developed into a movement for autonomy or independence of the former PDRY.

In 2009 prominent Southern Islamist leader Tariq al-Fadhli, who had fought for the Mujahideen in the Soviet–Afghan War, broke his alliance with President Saleh to join the secessionist South Yemen Movement, which gave a new thrust to the Southern movement, in which al-Fadhli for some time became a prominent figure. That same year, on 28 April, a revolt in the South started again, with massive demonstrations in most major towns.[10]

See also

- South Yemen Movement

- List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

References

- Halliday, Fred (2002). Revolution and Foreign Policy: The Case of South Yemen, 1967–1987. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-521-89164-7.

- Kifner, John (9 February 1986). "Massacre with Tea: Southern Yemen at War". New York Times. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- Brehony, Noel (2011). Yemen Divided: The Story of a Failed State in South Arabia. London: I. B. Tauris. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-84885-635-6.

- Busky, Donald (2002). Communism in History and Theory: Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Greenwood. p. 74. ISBN 0-275-97733-1.

- Ramazani, Rouhollah K.; Kechichian, Joseph A. (1988). The Gulf Cooperation Council: Record and Analysis. University of Virginia Press. p. 125. ISBN 0-8139-1148-6.

- Hurd, Robert; Noakes, Greg (July–August 1994). "North and South Yemen Lead Up to the Break Up". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. p. 48.

- Jonsson, Gabriel (2006). Towards Korean Reconciliation: Socio-cultural Exchanges and Cooperation. Ashgate. pp. 38–40. ISBN 0-7546-4864-8.

- Coswell, Alan (October 20, 1989). "2 Yemens Let Animosity Fizzle into Coziness". New York Times.

- Brehony, Noel (2011). Yemen Divided: The Story of a Failed State in South Arabia. London: I. B. Tauris. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-1-84885-635-6.

- Yemen: Behind Al-Qaeda Scenarios, an unfolding stealth agenda [Voltaire Network]