University of Salamanca

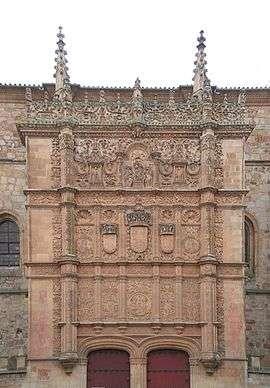

The University of Salamanca (Spanish: Universidad de Salamanca) is a Spanish higher education institution, located in the city of Salamanca, west of Madrid, in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It was founded in 1134 and given the Royal charter of foundation by King Alfonso IX in 1218. It is the world's third oldest university still in operation and the oldest university in the Hispanic world. The formal title of "University" was granted by King Alfonso X in 1254 and recognized by Pope Alexander IV in 1255.

Universidad de Salamanca | |

Seal of the University of Salamanca | |

| Latin: Universitas Studii Salamanticensis | |

| Motto | Omnium scientiarum princeps Salmantica docet (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | The principles of all sciences are taught in Salamanca |

| Type | Public |

| Established | Unknown; teaching existed since at least 1130. It was chartered by the pope Alexander IV in 1255.[1] |

| Rector | Ricardo Rivero Ortega |

Academic staff | 2,453[2] |

Administrative staff | 1,252[2] |

| Students | ca. 28,000[3] |

| 2,240[3] | |

| Location | , |

| Campus | Urban/College Town |

| Colours | Carmine |

| Affiliations | EUA, Coimbra Group |

| Website | www.usal.es |

| |

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| Global – Overall | |

| ARWU World[4] | 601-700 (2019) |

| CWTS World[5] | 699 (2019) |

| THE World[6] | 601–800 (2020) |

| USNWR Global[7] | 651 (2020) |

| QS World[8] | 601-650 (2020) |

History

Its origin, like all older universities, was a cathedral school, whose existence can be traced back to 1130. The university was founded in 1134 and recognized as a "General School of the Kingdom" by the Leonese King Alfonso IX in 1218. Granted Royal Chart by King Alfonso X, dated 8 May 1254, as the University of Salamanca this established the rules for organization and financial endowment.

On the basis of a papal bull by Alexander IV in 1255, which confirmed the Royal Charter of Alfonso X,[9] the school obtained the title of University.

The historical phrases Quod natura non dat, Salmantica non praestat (what nature does not give, Salamanca does not lend, in Latin) and Multos et doctissimos Salmantica habet (many and very versed Salamanca has) give an idea of the prestige the institution rapidly acquired.[10]

In the reign of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, the Spanish government was revamped. Contemporary with the Spanish Inquisition, the expulsion of the Jews and Muslims, and the conquest of Granada, there was a certain professionalization of the apparatus of the state. This involved the massive employment of "letrados", i.e., bureaucrats and lawyers, who were "licenciados" (university graduates), particularly, of Salamanca, and the newly founded University of Alcalá. These men staffed the various councils of state, including, eventually, the Consejo de Indias and Casa de Contratacion, the two highest bodies in metropolitan Spain for the government of the Spanish Empire in the New World.

While Columbus was lobbying the King and Queen for a contract to seek out a western route to the Indies, he made his case to a council of geographers at the University of Salamanca. In the next century, the morality of colonization in the Indies was debated by the School of Salamanca, along with questions of economics, philosophy and theology.

By the end of the Spanish Golden Age (c. 1550–1715), the quality of academics in Spanish universities declined. The frequency of the awarding of degrees dropped, the range of studies shrank, and there was a sharp decline in the number of its students. The centuries-old European wide prestige of Salamanca declined.

Like Oxford and Cambridge, Salamanca had a number of colleges (Colegios Mayores). These were founded as charitable institutions to enable poor scholars to attend the university. By the eighteenth century they had become closed corporations controlled by the families of their founders, and dominated the university between them. Most were destroyed by Napoleon's troops. Today some have been turned into faculty buildings while others survive as halls of residence.

In the 19th century, the Spanish government dissolved the university's faculties of canon law and theology. They were later reestablished in the 1940s as part of the Pontifical University of Salamanca.

Related affairs

The faculty of this university discussed the feasibility of Christopher Columbus's project and the effects his claims brought. Once America was discovered, they discussed the rights of indigenous people as being recognized with full plenitude, which was revolutionary for that period, economic processes were analyzed for the first time and they developed the science of law as it became a classical scholarly focus. It was the period when some of the brightest minds attended the university and it was known as the School of Salamanca. The school's members renovated theology, laid the foundation for modern-day law, international law, modern economic science and actively participated in the Council of Trent. The school's mathematicians studied the calendar reform, commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII and proposed the solution that was later implemented. By 1580, 6,500 new students had arrived at Salamanca each year, amongst the graduates were state officials of the Spanish monarchy administration were nourished. It was also during this period when the first female university students were probably admitted, Beatriz Galindo and Lucía de Medrano, the latter being the first woman ever to give classes at a university.

Present day

Salamanca draws undergraduate and graduate students from across Spain and the world; it is the top-ranked university in Spain based on the number of students coming from other regions.[11] It is also known for its Spanish courses for non-native speakers, which attract more than two thousand foreign students each year.[12]

Today the University of Salamanca is an important center for the study of humanities and is particularly noted for its language studies, as well as in laws and economics. Scientific research is carried out in the university and research centers associated with it, such as at the Centro de Investigación del Cáncer [Cancer Research Centre],[13] Instituto de Neurociencias de Castilla y León or INCyL [Institute of Neuroscience of Castile and León],[14] Centro de Láseres Pulsados Ultracortos Ultraintensos [Ultrashort Ultraintense Pulse Lasers Centre].

In conjunction with the University of Cambridge, the University of Salamanca co-founded the Association of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE) in 1989.

In 2018, the institution will celebrate its eighth centennial, for which preparations are currently being made.[15]

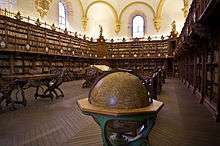

Library

The library holds about 906,000 volumes.[16]

Notable people

Notable staff

- Juan de Galavís, professor of theology; later became Archbishop of Santo Domingo and Archbishop of Bogotá

- Francisco Elías de Tejada y Spínola, professor of Philosophy of Law and Natural Law

- Enrique Gil Robles, professor of Natural Law

- Paul Nuñez Coronel (d.1534), professor of Hebrew

- Miguel de Unamuno, writer

- Beatriz Galindo, (d. 1534), professor of Latin and rhetoric

Notable students

- Miguel de Cervantes, author

- Luis de Góngora

- Hernán Cortés

- Fray Luis de León

- Francisco de Vitoria

- Pedro Calderón de la Barca

- Bartolomé de Las Casas

- Beatriz Galindo

- Miguel de Unamuno

Other notable students and academic teachers include:

- Aristides Royo, President of Panama

- Francisco J. Ayala

- Susana Marcos Celestino

- Abraham Zacuto

- Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate

- Esteban de Bilbao Eguía

- Domingo de Soto

- Melchor Cano

- Francisco Suárez

- St. John of the Cross

- Antonio de Nebrija

- Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares

- Gaspar Sanz

- Pedro Gómez Labrador, Marquis of Labrador

- Cardinal Mazarin

- Mateo Alemán

- Diego de Torres Villarroel

- Pedro Salinas

- Adolfo Suárez

- Juan Zarate

- Manuel Belgrano

- Luis de Onís

- Pedro Nunes

- Simón de Rojas

- Antonio Tovar

- Gaspar Cervantes de Gaeta

Notes and references

- ÁLVAREZ VILLAR, Julián (1993), La Universidad de Salamanca: arte y tradiciones, ISBN 847481751X

- University of Salamanca. "Personal" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- University of Salamanca. "Estudiantes" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities - University of Salamanca". Shanghai Ranking. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- "CWTS Leiden Ranking 2019". Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- "World University Rankings - University of Salamanca". THE World University Rankings. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- "Best Global Universities - University of Salamanca". U.S. News Education (USNWR). Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- "QS World University Rankings - University of Salamanca". Top Universities. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- University of Salamanca, A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF SALAMANCA.

- VIII Centenario de la Universidad de Salamanca - Reseña Histórica de la Universidad de Salamanca:. Centenario.usal.es. Retrieved on 2013-09-05.

- http://www.usal.es/webusal/files/Discurso_rector_Inauguracion_09_10_0.pdf

- La USAL inaugura los cursos de verano con 2.000 estudiantes extranjeros. elmundo.es. Retrieved on 2013-09-05.

- http://www.cicancer.org/

- (in Spanish) INCyL. INCyL. Retrieved on 2013-09-05.

- VIII Centenario de la Universidad de Salamanca - VIII Centenario de la Universidad de Salamanca. Centenario.usal.es. Retrieved on 2013-09-05.

- Spain – Libraries and museums

Literature

- Manuel Fernández Álvarez, Luis E. Rodríguez San Pedro & Julián Álvarez Villar, The University of Salamanca, Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 1992. ISBN 84-7481-701-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to University of Salamanca. |

- University website

- VIII Centenario website

- University of Salamanca language courses. Official spanish courses website

- Language courses in Salamanca University, marketed by a private company, Accom Consulting Spain S. L., an authorized University agent

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.