Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (Italian: Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

Italian Communist Party Partito Comunista Italiano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | PCI |

| General Secretaries | Palmiro Togliatti Luigi Longo Enrico Berlinguer Alessandro Natta Achille Occhetto |

| Founded | 21 January 1921 (as Communist Party of Italy) 15 May 1943 (as Italian Communist Party) |

| Dissolved | 3 February 1991 |

| Preceded by | Italian Socialist Party |

| Succeeded by | Democratic Party of the Left[1][2] (main successor) Communist Refoundation Party (split) |

| Headquarters | Via delle Botteghe Oscure 4, Rome |

| Newspaper | l'Unità |

| Youth wing | Communist Youth Federation |

| Membership | 989,708 (1991) 2,252,446 (1947)[3] |

| Ideology | Communism Marxism–Leninism[4][5][6] in the late years also: Revisionism[7] Democratic socialism |

| Political position | Before 1940s: Left-wing to far-left[8][9] After 1940s: Left-wing |

| National affiliation | National Liberation Committee (1943–47) Popular Democratic Front (1947–56) |

| International affiliation | Comintern (1921–1943) Cominform (1947–1956) |

| European Parliament group | Communists and Allies (1973–1989) European United Left (1989–1991) |

| Colours | Red |

| Party flag | |

| |

The PCI was founded as the Communist Party of Italy on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). Amadeo Bordiga and Antonio Gramsci led the split. Outlawed during the Fascist regime, the party played a major role in the Italian resistance movement. It changed its name in 1943 to PCI and became the second largest political party of Italy after World War II, attracting the support of about a third of the vote share during the 1970s. At the time, it was the largest communist party in the West, with peak support reaching 2.3 million members, in 1947,[10] and peak share being 34.4% of the vote (12.6 million votes) in the 1976 general election.

The PCI travelled from doctrinaire communism to democratic socialism by the 1970s or the 1980s.[11][12][13][14][15][16] In 1991, it was dissolved and re-launched as the Democratic Party of the Left (PDS), which joined the Socialist International and the Party of European Socialists. The more radical members of the organization formally departed to establish the Communist Refoundation Party (PRC).

History

Early years

The roots of the Italian Communist Party date back to 1921, when the Communist Party of Italy (Partito Comunista d'Italia, PCd'I) was founded in Livorno on 21 January, following a split in the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) on their 17th Congress. The split occurred after the socialist Congress of Livorno refused to expel the reformist group as required by the Comintern. The main factions of the new party were L'Ordine Nuovo, based in Turin and led by Antonio Gramsci, and the "maximalist" faction led by Nicola Bombacci. Amedeo Bordiga was elected Secretary of the new party.[17]

In the same year, PCd'I participated to its first general election, obtaining 4.6% of the vote and 15 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. At the time, it was an active yet small faction within Italian political left, which was strongly led by the Socialist Party, while on the international plane it was part of Soviet-led Comintern.

In 1926, the Fascist government of Benito Mussolini outlawed the Communist Party. Although forced underground, the PCd'I maintained a clandestine presence within Italy during the years of the Fascist regime. Many of its leaders were also active in exile. During its first year as a banned party, Antonio Gramsci defeated the party's left-wing which was led by Amadeo Bordiga, becoming the new Secretary during the party's congress in Lyon and issued a manifesto expressing the programmatic basis of the party. However, Gramsci soon found himself jailed by Mussolini's regime and the leadership of the party passed to Palmiro Togliatti. In 1930, Bordiga was expelled from the party on the charge of Trotskyism. The same fate had already occurred to members of the party's right-wing.

On 15 May 1943, the party changed its official name in Partito Comunista Italiano (Italian Communist Party), often shortened PCI.

World War II

After the fall of Mussolini's regime on 25 July 1943, the Communist Party returned formally legal, playing a major role during the national liberation, known in Italy as Resistenza ("Resistance") and forming many partisan groups.

In the April 1944 after the so-called svolta di Salerno (Salerno's turn), Togliatti agreed to cooperate with King Victor Emmanuel III and his Prime Minister, the Marshal Pietro Badoglio. After the turn, Communists took part in every government during the national liberation and constitutional period from June 1944 to May 1947.[18] The Communists' contribution to the new Italian democratic constitution was decisive. The so-called "Gullo decrees" of 1944, for instance, sought to improve social and economic conditions in the countryside.[19] During Badoglio and Ferruccio Parri's cabinets, Togliatti served as Deputy Prime Minister.

During the Resistance, the PCI became increasingly popular, as the majority of partisans were communists. The Garibaldi Brigades, promoted by the PCI, were among the more numerous partisan forces.[20]

Post-war years

The PCI took part in the 1946 Italian general election and referendum, campaigning for the "republic". In the election, the Communists arrived third, behind the Christian Democracy (DC) and the Socialist Party, gaining almost 19% of votes and electing 104 members of the Constituent Assembly.[21] While the popular referendum resulted in the replacement of the monarchy with a republic,[22] with the 54% of votes in favour and 46% against.[23][24]

In May 1947, the PCI was excluded from the government. The Christian democratic Prime Minister, Alcide De Gasperi, was losing popularity, and feared that the leftist coalition would take power. While the PCI was growing particularly fast due to its organizing efforts supporting sharecroppers in Sicily, Tuscany and Umbria, movements which were also bolstered by the reforms of Fausto Gullo, the Communist Minister of Agriculture.[25] On 1 May, the nation was thrown into crisis by the murder of eleven leftist peasants (including four children) at an International Workers' Day parade in Palermo by Salvatore Giuliano and his gang. In the political chaos which ensued, the president engineered the expulsion of all left-wing ministers from the cabinet on 31 May. The PCI would not have a national position in government again. De Gasperi did this under pressure from US Secretary of State George Marshall, who'd informed him that anti-communism was a pre-condition for receiving American aid,[26][25] and Ambassador James C. Dunn who had directly asked de Gasperi to dissolve the parliament and remove the PCI.[27]

In the general election of 1948, the party joined the PSI in the Popular Democratic Front (FDP), but it was defeated by the Christian Democracy party. The United States spent over $10 million to support anti-PCI groups in the election.[28] Fearful of the possible FDP's electoral victory, the British and American governments also undermined the quest for justice by tolerating the efforts made by Italy's top authorities to prevent any of the alleged Italian war criminals from being extradited and taken to court.[29][30] The denial of Italian war crimes was backed up by the Italian state, academe, and media, re-inventing Italy as only a victim of the German Nazism and the post-war Foibe massacres.[29]

The party gained considerable electoral success during the following years and occasionally supplied external support to centre-left governments, although it never directly joined a government. It successfully lobbied Fiat to set up the AvtoVAZ (Lada) car factory in the Soviet Union (1966). The party did best in Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany and Umbria, where it regularly won the local administrative elections; and in some of the industrialized cities of Northern Italy. At the city government level during the course of the post-war period, the PCI demonstrated (in cities like Bologna and Florence) their capacity for uncorrupt, efficient and clean government.[31] After the elections of 1975, the PCI was the strongest force in nearly all of the municipal councils of the great cities.[32]

From the 1950s to 1960s

The Soviet Union's brutal suppression of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 created a split within the PCI. The party leadership, including Palmiro Togliatti and Giorgio Napolitano (who in 2006 became President of the Italian Republic), regarded the Hungarian insurgents as counter-revolutionaries as reported at the time in l'Unità, the official PCI newspaper. However, Giuseppe Di Vittorio, chief of the communist trade union Italian General Confederation of Labour (CGIL), repudiated the leadership position as did prominent party member Antonio Giolitti and Italian Socialist Party national secretary Pietro Nenni, a close ally of the PCI. Napolitano later hinted at doubts over the propriety of his decision.[33] He would eventually write in From the Communist Party to European Socialism. A Political Autobiography (Dal Pci al socialismo europeo. Un'autobiografia politica) that he regretted his justification of the Soviet intervention, but quieted his concerns at the time for the sake of party unity and the international leadership of Soviet Communism.[34] Giolitti and Nenni went on to split with the PCI over this issue. Napolitano became a leading member of the miglioristi faction within the PCI which promoted a social-democratic direction in party policy.[35]

In the mid-1960s, the United States State Department estimated the party membership to be approximately 1,350,000 (4.2% of the working age population, proportionally the largest communist party in the capitalist world at the time and the largest party at all in whole Western Europe with the German Social Democratic Party).[36] United States government sources have claimed that the party was receiving $40–50 million per year from the Soviets while the United States investment in Italy was $5–6 million.[37] However, declassified information shows this to be exaggerated,[38] although the PCI relied on Soviet financial assistance more than any other communist party supported by Moscow.[38]

According to the former KGB archivist Vasili Mitrokhin, Longo and other PCI leaders became alarmed at the possibility of a coup in Italy after the Athens Colonel Coup in April 1967. These fears were not completely unfounded as there had been two attempted coups in Italy, Piano Solo in 1964 and Golpe Borghese in 1970, by military and neo-fascist groups. The PCI’s Giorgio Amendola formally requested Soviet assistance to prepare the party in case of such an event. The KGB drew up and implemented a plan to provide the PCI with its own intelligence and clandestine signal corps. From 1967 through 1973, PCI members were sent to East Germany and Moscow to receive training in clandestine warfare and information gathering techniques by both the Stasi and the KGB. Shortly before the May 1972 elections, Longo personally wrote to Leonid Brezhnev asking for and receiving an additional $5.7 million in funding. This was on top of the $3.5 million that the Soviet Union gave the PCI in 1971. The Soviets also provided additional funding through the use of front companies providing generous contracts to PCI members.[39]

Enrico Berlinguer

In 1969, Enrico Berlinguer, PCI deputy national secretary and later secretary general, took part in the international conference of the Communist parties in Moscow, where his delegation disagreed with the "official" political line and refused to support the final report. Unexpectedly to his hosts, his speech challenged the Communist leadership in Moscow. He refused to "excommunicate" the Chinese Communists and directly told Leonid Brezhnev that the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact countries (which he called the "tragedy in Prague") had made clear the considerable differences within the communist movement on fundamental questions such as national sovereignty, socialist democracy and the freedom of culture. At the time the PCI, which had absorbed the PSI's left-wing, the Italian Socialist Party of Proletarian Unity, so strengthening its leadership over the Italian left, was the largest communist party in a capitalist state, garnering 34.4% of the vote in the 1976 general election.

Relationships between the PCI and the Soviet Union gradually fell apart as the party moved away from Soviet obedience and Marxist–Leninist orthodoxy in the 1970s and 1980s and toward Eurocommunism and the Socialist International. The PCI sought a collaboration with Socialist and Christian Democracy parties (the Historic Compromise). However, Christian Democrat party leader Aldo Moro's kidnapping and murder by the Red Brigades in May 1978 put an end to any hopes of such a compromise. The compromise was largely abandoned as a PCI policy in 1981. The Proletarian Unity Party merged into the PCI in 1984.

During the Years of Lead, the PCI strongly opposed the terrorism and the Red Brigades, who in turn murdered or wounded many PCI members or trade unionists close to the PCI. According to Mitrokhin, the party asked the Soviets to pressure the Czechoslovakian State Security (StB) to withdraw their support to the group, which Moscow was unable or unwilling to do.[39] This as well as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan led to a complete break with Moscow in 1979. In 1980, the PCI refused to participate in the international conference of communist parties in Paris although cash payments to the PCI continued until 1984.[38]

Dissolution

Achille Occhetto became general secretary of the PCI in 1988. At a 1989 conference in a working-class section of Bologna, Occhetto stunned the party faithful with a speech heralding the end of Communism, a move now referred to in Italian politics as the svolta della Bolognina (Bolognina turning point). The collapse of the Communist governments in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe led Occhetto to conclude that the era of Eurocommunism was over. Under his leadership, the PCI dissolved and refounded itself as the Democratic Party of the Left, which branded itself as a progressive left-wing and democratic socialist party. A third of the PCI membership, led by Armando Cossutta, refused to join the PDS and instead seceded to form the Communist Refoundation Party.[40]

Popular support

In all its history, the PCI was particularly strong in Central Italy, in the so-called "Red Regions" of Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria and Marche, as well as in the industrialized cities of Northern Italy. However, Communists' municipal showcase was Bologna, which was held continuously by the PCI from 1945 onwards. Amongst other measures, the local PCI administration tackled urban problems with successful programmes of health for the elderly, nursery education and traffic reform[41] while also undertaking initiatives in housing and school meal provisions.[42] From 1946 to 1956, the Communist city council built 31 nursery schools, 896 flats and 9 schools. Health care improved substantially, street lighting was installed, new drains and municipal launderettes were built and 8,000 children received subsidised school meals. In 1972, the then-mayor of Bologna, Renato Zangheri, introduced a new and innovative traffic plan with strict limitations for private vehicles and a renewed concentration on cheap public transport. Bologna's social services continued to expand throughout the early and mid-1970s. The city centre was restored, centres for the mentally sick were instituted to help those who had been released from recently closed psychiatric hospitals, handicapped persons were offered training and found suitable jobs, afternoon activities for schoolchildren were made less mindless than the traditional doposcuola (after-school activities) and school programming for the whole day helped working parents.[32] Communists administrations at a local level also helped to aid new businesses while also introducing innovative social reforms.

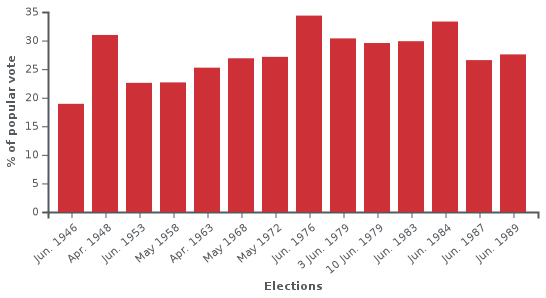

The electoral results of the PCI in general (Chamber of Deputies) and European Parliament elections since 1946 are shown in the chart below.

Election results

Italian Parliament

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||

| Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 304,719 (7th) | 4.6 | 15 / 535 |

||

| 1924 | 268,191 (6th) | 3.6 | 19 / 535 |

||

| 1929 | banned | - | 0 / 400 |

||

| 1934 | banned | - | 0 / 400 |

- | |

| 1946 | 4,356,686 (3rd) | 18.9 | 104 / 556 |

||

| 1948 | 8,136,637 (2nd)[lower-alpha 1] | 31.0 | 130 / 574 |

||

| 1953 | 6,120,809 (2nd) | 22.6 | 143 / 590 |

||

| 1958 | 6,704,454 (2nd) | 22.7 | 140 / 596 |

||

| 1963 | 7,767,601 (2nd) | 25.3 | 166 / 630 |

||

| 1968 | 8,557,404 (2nd) | 26.9 | 177 / 630 |

||

| 1972 | 9,072,454 (2nd) | 27.1 | 179 / 630 |

||

| 1976 | 12,622,728 (2nd) | 34.4 | 228 / 630 |

||

| 1979 | 11,139,231 (2nd) | 30.4 | 201 / 630 |

||

| 1983 | 11,032,318 (2nd) | 29.9 | 198 / 630 |

||

| 1987 | 10,254,591 (2nd) | 26.6 | 177 / 630 |

||

| Senate of the Republic | |||||

| Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 6,969,122 (2nd)[lower-alpha 1] | 30.8 | 50 / 237 |

||

| 1953 | 6,120,809 (2nd) | 22.6 | 56 / 237 |

||

| 1958 | 6,704,454 (2nd) | 22.2 | 60 / 246 |

||

| 1963 | 6,933,842 (2nd) | 25.2 | 84 / 315 |

||

| 1968 | 8,583,285 (2nd) | 30.0 | 101 / 315 |

||

| 1972 | 8,475,141 (2nd) | 28.1 | 94 / 315 |

||

| 1976 | 10,640,471 (2nd) | 33.8 | 116 / 315 |

||

| 1979 | 9,859,004 (2nd) | 31.5 | 109 / 315 |

||

| 1983 | 9,579,699 (2nd) | 30.8 | 107 / 315 |

||

| 1987 | 9,181,579 (2nd) | 28.3 | 101 / 315 |

||

- Into the Popular Democratic Front.

European Parliament

| European Parliament | |||||

| Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 10,361,344 (2nd) | 29.6 | 24 / 81 |

||

| 1984 | 11,714,428 (1st) | 33.3 | 27 / 81 |

||

| 1989 | 9,598,369 (2nd) | 27.6 | 22 / 81 |

||

Leadership

- Secretary: Antonio Gramsci (1926), Camilla Ravera (1927–1930), Palmiro Togliatti (1930–1934), Ruggero Grieco (1934–1938), Palmiro Togliatti (1938–1964), Luigi Longo (1964–1972), Enrico Berlinguer (1972–1984), Alessandro Natta (1984–1988), Achille Occhetto (1988–1991)

- President: Luigi Longo (1972–1980), Alessandro Natta (1989–1990), Aldo Tortorella (1990–1991)

- Leader in the Chamber of Deputies: Luigi Longo (1946–1947), Palmiro Togliatti (1947–1964), Pietro Ingrao (1964–1972), Alessandro Natta (1972–1979), Fernando Di Giulio (1979–1981), Giorgio Napolitano (1981–1986), Renato Zangheri (1986–1990), Giulio Quercini (1990–1991)

- Leader in the Senate: Mauro Scoccimarro (1948–1958), Umberto Terracini (1958–1973), Edoardo Pema (1973–1986), Gerardo Chiaromonte (1983–1986), Ugo Pecchioli (1986–1991)

- Leader in the European Parliament: Giorgio Amendola (1979–1980), Guido Fanti (1980–1984), Giovanni Cervetti (1984–1989), Luigi Alberto Colajanni (1989–1991)

Symbols

1921–1945

1921–1945 1945–1951

1945–1951 1951–1991

1951–1991

References

- Ignazi, Pietro (1992). Il mulino (ed.). Dal PCI al PDS. ISBN 9788815034137.

- Bellucci, Paolo; Maraffi, Marco; Segatti, Paolo (2000). Donzelli (ed.). PCI, PDS, DS: la trasformazione dell'identità politica della sinistra di governo. ISBN 9788879895477.

- "Iscritti". Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- De Rosa, Gabriele; Monina, Giancarlo (2003). Rubbettino (ed.). L'Italia repubblicana nella crisi degli anni Settanta: Sistema politico e istitutzioni. p. 79. ISBN 9788849807530.

- Cortesi, Luigi (1999). FrancoAngeli (ed.). Le origini del PCI: studi e interventi sulla storia del comunismo in Italia. p. 301. ISBN 9788846413000.

- La Civiltà Cattolica. 117. 1966. pp. 41–43. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Morando, Enrico (2010). Donzelli (ed.). Riformisti e comunisti?: dal Pci al Pd : I "miglioristi" nella politica italiana. pp. 54–57. ISBN 9788860364821.

- Tobagi, Walter (2009). Il Saggiatore (ed.). La rivoluzione impossibile: l'attentato a Togliatti, violenza politica e reazione popolare. p. 35. ISBN 9788856501124.

- Robbe, Federico (2012). FrancoAngeli (ed.). L'impossibile incontro: gli Stati Uniti e la destra italiana negli anni Cinquanta. p. 203. ISBN 9788856848304.

- "Iscritti ai partiti". Archived 1 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Guide to the Italian Communist Party Collection, 1969-1971 1613". libraries.psu.edu.

- Joan Barth Urban (1986). Moscow and the Italian Communist Party: From Togliatti to Berlinguer. I.B.Tauris. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-85043-027-8.

- Enrico Morando (2010). Riformisti e comunisti?: dal Pci al Pd : i "miglioristi" nella politica italiana nella politica italiana. Donzelli Editore. p. 42. ISBN 978-88-6036-482-1.

- "Il socialismo democratico abita a Botteghe Oscure".

- "European Socialist Question Communist Party Independence".

- "Correnti interne al PCI".

- Paolo Spriano, Storia del Partito comunista italiano, Einaudi, 1967

- Monanelli, Cervi Storia d'Italia Rcs Quotidiani 2003

- Paul Ginsborg. A History of Contemporary Italy: Society and Politics, 1943-1988. Google Books. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- G. Bianchi, La Resistenza, Storia d'Italia, vol. 8, p. 368

- Ministry of the Interior – 1946 Election Result

- "Dipartimento per gli Affari Interni e Territoriali". elezionistorico.interno.gov.it.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Savoia - Nuovi Dizionari Online Simone - Dizionario Storico del Diritto Italiano ed Europeo Indice H". simone.it.

- Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy, pp. 106–113

- James Ciment, Encyclopedia of Conflicts Since World War II (Routledge, 2015)

- Corke, Sarah-Jane (12 September 2007). US Covert Operations and Cold War Strategy: Truman, Secret Warfare and the CIA, 1945-53. Routledge. pp. 47–48. ISBN 9781134104130.

- Corke, Sarah-Jane (12 September 2007). US Covert Operations and Cold War Strategy: Truman, Secret Warfare and the CIA, 1945-53. Routledge. pp. 49–58. ISBN 9781134104130.

- Italy's bloody secret (Archived by WebCite®), written by Rory Carroll, Education, The Guardian, June 2001

- Effie Pedaliu (2004) Britain and the 'Hand-over' of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48. Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 39, No. 4, Special Issue: Collective Memory, pp. 503–529 JSTOR 4141408

- David Robertson (1993; 2nd edition). The Penguin Dictionary of Politics.

- Paul Ginsborg. A History of Contemporary Italy: Society and Politics, 1943-1988.

- The Italian Communists: foreign bulletin of the P.C.I., No. 4. Rome. October–December 1980. p. 103.

- Napolitano, Giorgio (2005). Dal Pci al socialismo europeo. Un'autobiografia politica (in Italian). Laterza. ISBN 978-88-420-7715-2.

- Paolo Cacace. "Napolitano e l'"utopia mite" dell'Europa" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- Benjamin, Roger W. and Kautsky, John H. (March 1968). Communism and Economic Development in the American Political Science Review. Vol. 62. No. 1 pp. 122.

- Carl Colby (director) (September 2011). The Man Nobody Knew: In Search of My Father, CIA Spymaster William Colby (Motion picture). New York City: Act 4 Entertainment. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

Edward Luttwak, interview: "[W]e estimated at the time they were getting $40–50 million a year at a time when we were putting $5–6 million into Italian politics.

- Richard Drake (Summer 2004). The Soviet Dimension of Italian Communism. Journal of Cold War Studies. Vol. 6. No. 3. pp. 115–119.

- Andrew, Christopher and Mitrokhin, Vasili (2001). The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. Basic Books.

- Kertzer, David I. (1998). Politics and Symbols: The Italian Communist Party and the Fall of Communism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07724-7.

- Library of Nations: Italy, Time Life Books (1985).

- Cyrille Guiat. The French and Italian Communist Parties: Comrades and Culture. Google Books. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Partito Comunista Italiano. |