League of Communists of Yugoslavia

The League of Communists of Yugoslavia (Serbo-Croatian: Savez komunista Jugoslavije / Савез комуниста Југославије),[lower-alpha 1] known until 1952 as the Communist Party of Yugoslavia,[lower-alpha 2] was the founding and ruling party of SFR Yugoslavia. It was formed in 1919 as the main communist opposition party in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and after its initial successes in the elections, it was proscribed by the royal government and was at times harshly and violently suppressed. It remained an illegal underground group until World War II when, after the Invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941, the military arm of the party, the Yugoslav Partisans, became embroiled in a bloody civil war and defeated the Axis powers and their local auxiliaries. After the liberation from foreign occupation in 1945, the party consolidated its power and established a one-party state, which existed until the 1990 breakup of Yugoslavia.

League of Communists of Yugoslavia Serbo-Croatian: Савез комуниста Југославије, Savez komunista Jugoslavije Slovene: Zveza komunistov Jugoslavije Macedonian: Сојуз на комунистите на Југославија, Sojuz na komunistite na Jugoslavija | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Leader | Josip Broz Tito (most prominent, see list of leaders) |

| Founded | 1919 Vukovar Congress in 1920 |

| Dissolved | 1990 |

| Succeeded by | SPS SDP SDP BiH SD SDSM DPS SK - PJ SRSJ |

| Headquarters | Building of Socio-Political Organizations (1965–90), Belgrade, SFR Yugoslavia |

| Newspaper | Borba |

| Youth wing | League of Communist Youth of Yugoslavia Union of Pioneers of Yugoslavia |

| Military wing | Yugoslav Partisans (1941–1945) |

| Ideology | Communism Marxism–Leninism Titoism Anti-fascism Yugoslavism Yugoslav irredentism[1] |

| Political position | Left-wing[2] to far-left |

| International affiliation | none Comintern until 1943, Cominform until 1948 |

| Colours | Red |

| Party flag | |

| |

| |

The party, which was led by Josip Broz Tito from 1937 to 1980, was the first communist party in power in the history of the Eastern Bloc that openly opposed the Soviet Union and thus was expelled from the Cominform in 1948 in what is known as the Tito–Stalin split. After internal purges of pro-Soviet members, the party renamed itself the League of Communists in 1952 and adopted the politics of workers' self-management and independent communism, known as Titoism.

Founding

-Beograd.jpg)

When the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was created after World War I, the different social democratic parties that had existed in Austria-Hungary, Serbia and Montenegro called for a unification of their parties. The idea was widely accepted by parties and organizations from all over the country and in April 1919 a Congress of Unification was held in Belgrade, attended by 432 delegates representing 130,000 organized supporters of the workers’ class movement from all parts of the Kingdom except Slovenia. The ministerial branch of the Social democrat party of Slovenia was minorized in April 1920, when the Slovenes joined ranks with other social-democrats turned Marxist–Leninist revolutionaries. Slovenes joined officially at the Second Congress, held in Vukovar in late April 1920.

The congress was marked by opposing positions towards the concepts of the revolutionary and reformist currents. Bolshevik influence was introduced by soldiers who during the war had been captured by Russian forces and had experienced the October Revolution. The Congress decided to form a single political party (not a federation of parties) named Socialist Labor Party of Yugoslavia (of Communists) (Socijalistička radnička partija Jugoslavije (komunista)) which would be a member of Comintern. Its highest organs, to which all other organs were subordinate, were the Congress and the Central Committee, headed by Filip Filipović and Živko Topalović as political secretaries and Vladimir Ćopić as organizational secretary. The party program, the Basis of Unification, was a "synthesis of the Social Democratic ideological heritage with the experiences of the October Revolution", spoke in terms of an imminent revolution, while the Practical Program of Action was oriented to a long-term political struggle within the capitalist system. The party considered the national question to be solved by the events of 1918, supported a unitarian state merging the different "tribes" into one "nation" as the best basis of class struggle, and opposed ″federalism".

In the wake of the Congress, the United Socialist (Communist) Woman Movement (Jedinstveni ženski socijalistički (komunistički) pokret), and the Central Workers’ Trade-Union Council (Centralno radničko sindikalno vijeće) were also founded, while the Young Communist League of Yugoslavia was formed later that year.

Period of legal activity

The newly formed party organized several protests against political situations in the country and rallies of support for Soviet Russia and the Hungarian Soviet Republic, while the Central Workers’ Trade-Union Council organized many strikes and demonstrations against employers and state authority.

The party achieved gains in many towns and villages during the local elections of March 1920 in Croatia and Montenegro (the latter being an entity inside Serbia at this stage), where Communists won majority in several cities (including big cities like Zagreb, Osijek, Slavonski Brod, Križevci and Podgorica) resulted in the anxious government using pressure against the party: it refused to confirm Communist administrations of these districts and imprisoned the party leadership, which however was subsequently released after a hunger strike. These early successes convinced other groups, including Social Democrats in Slovenia, to join the party.

Success continued in local elections in Serbia (including the Macedonia region which it then included) in the summer of 1920, in which the Communists won majorities in many districts (including Belgrade, Skoplje and Niš). Again, Communist administrations were suspended by the government.

Finally, in elections to the Constitutional Assembly, held on November 28, 1920, the Communist Party received 198,736 votes (12.36% of all votes) and 58 of 419 seats in the assembly.

Split with the Centrists

But the growth of the party also incited arguments about party's agenda and resulted in a split between two currents: The reformist Centrists, stressing that the Kingdoms was an industrially underdeveloped state and not ripe for revolution, opposed an emphasis on class struggle and a close connection between the party and the trade-unions and favored participating in the political life by legal means and working towards social reforms. The decidedly Communist Revolutionaries, arguing that the prerequisites for a revolution already existed, favored a centralized party, a close alliance with the unions and the seizing of power by force, including terrorist tactics.

The 2nd party congress, held in June 1920 in Vukovar, saw the revolutionaries led by Filipović prevail. The party changed its name to Communist Party of Yugoslavia (Komunistička partija Jugoslavije) and elected Filipović and Sima Marković as political secretaries. The Congress also supported to the idea of a Balkan Communist Federation. The Centrists objected to their marginalization and in September published their Manifesto, in which they denounced the October Revolution as "irrational" and as "violence on the course of history" and the Bolsheviks as using the Comintern as an instrument of their foreign policy, using "all foreign parties as their own blind agents"[3] The manifesto was signed by 53 leading party members, which all were expelled from the leadership, while 62 members who had expressed solidarity with them were given party punishments. The centrists for a time formed their own party before they united with the Social Democrats in the Socialist Party of Yugoslavia.

Ban of the Communist party

The government, already anxious about a destabilization of the Kingdom but also encouraged by the demise of the Communist regime in Hungary, took measures against the revolutionary Communist Party after a policeman and four miners had been killed in a miners' strike near Tuzla, Bosnia: On the night from 29 to 30 December 1920, the government issued the Obznana (literally "announcement") decree, which prohibited all Communist activities until the adoption of the new constitution, excluding only the Communist deputies involvement in the Constitutional Assembly. The party's property was seized and several leaders arrested. The Assembly approved of the Constitution on 28 June 1921, against the votes of the Communist deputies.

The Communist Party reacted to the Obznana preparing a transition to illegal operation. In June 1921, it formed an Alternative Central Party Leadership, which would assume control of the Party if the Party leadership was arrested.

Some Communists reacted to the oppression by founding the terrorist group Crvena Pravda ("The Red Justice"), which organized assassination attempts: during the official proclamation of the constitution, they unsuccessfully tried to kill Prince Regent Alexander, but on 21 July 1921 they succeeded in assassinating Milorad Drašković, minister of the interior and author of the Obznana. This act was widely condemned and resulted in a lasting drop of the party's popularity. The Assembly passed the Law of protection of public security and state order (Zakon o zaštiti javne bezbednosti i poretka u državi), which indefinitely banned the Communist Party and all Communist activity. The ban was not lifted until the demise of the Kingdom in 1941.

At the same time all the Communist deputies were arrested and at the end of the year, some 70,000 Communists and trade-unions members had been arrested, while many members ceased activities altogether.

Underground organization

As the party continued underground and abroad, the Alternative Central Party Leadership was headed by Kosta Novaković, Triša Kaclerović and Moša Pijade. However, soon conflict flared up on the issue whether the party should attempt to reconstruct legal forms of its work or devote itself entirely to illegal activity. A group of party leaders, led by former party secretary Sima Marković, formed the Executive Committee of the Communist Party in Emigration in September 1921, thus establishing a double leadership. The two factions reunited at the 1st state Conference, held at Vienna in July 1922: Marković argued for postponing the revolution and aiming at constitutional changes, while Novaković wanted to aim for "rapid revolutionary change". Marković persuaded the majority and the Comintern confirmed the "right-wing" majority but also appealed to the "left-wing" by criticizing the former leadership. The Communists succeeded in reestablishing re-opening for itself a way into public political life via the Independent Trade Unions and organizations like the Union of Workers' Youth of Yugoslavia and the Independent Workers' Party of Yugoslavia, which however won only 1% of the votes and no seats in the parliamentary elections of March 1923.

The 2nd state conference held at Vienna in May 1923 saw a victory of the left wing, with Triša Kaclerović assuming leadership. The conference also decided that to create an illegal centralized cadre party, locate the leadership inside the country, infiltrate workers' organizations and set up combat units.

National question and factional strife

In 1923, the party also began to rethink its position on the national question and distanced itself from its former view, that 1918 had created a unified Yugoslav nation. Communists began to question the structure of the Yugoslav state and supported a Danubian–Balkan Federation. Debates were summed up by the 3rd state conference held at Belgrade in January 1924 which supported the concept of a federative republic with fully developed local self-management.

However, the Comintern denounced any federative organization and instead demanded the breaking up of the so-called "Versailles Yugoslavia", with Slovenia, Croatia and Macedonia forming independent republics. The Comintern, perceiving that the unsolved national question could be used to foster a new revolution, focused on Yugoslavia as the least stable of Balkan states.

The 3rd state conference also decided to strengthen the illegal party organization by the creation of party cells among industrial workers (instead of skilled craftsmen), the schooling party cadres and a united front with the trade-unions. This led to the increase of membership from 1,000 to 2,500 at the end of 1924.

The 3rd conference's decisions were accepted in a party referendum but rejected by the local Belgrade organization, led by trade union functionaries and Sima Marković, who refused to recognize the leadership under Kaclerović. They especially opposed the Comintern's policy of dissolving Yugoslavia, seeing no chance for a revolution and hence no need to foster it by such a move. The conflict was heightened by Croatian Communists open support for nationalist groups like the Croatian Peasant Party or the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO), and their directing complaints against Serbian hegemony not against the Serbian bourgeoisie but against the Serbian people. The Belgrade opposition was defeated in a renewed debate in autumn 1924 and subsequently left the party. The conflict was reviewed by the Comintern, which condemned Marković's views as "Social Democratic and opportunistic".

The 3rd party congress held at Vienna in May 1926, convoked to overcome the internal conflict, agreed with Comintern's evaluation and confirmed the 3rd state conference's as "the foundations for its ideological and political Bolshevization″. The Comintern's program was made binding on any party member and the party's name supplemented by "Section of the Communist International". The Congress also defined Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia, Montenegro and Vojvodina as non-Serb territories that should secede from the remaining "area of the Serbian Nation". Members of both party wings practiced "self-criticism", expressed their desire for unity and were subsequently elected into the Central Committee, with Marković returning as political secretary.

But the conflict was not truly resolved and began to spread into the lower party organizations, to which the party responded by anti-factional campaigns among the cadres. In January 1928, Đuro Đaković appealed to the Comintern, denounced both wings as blocking party work and marginalizing the party in the political life of Yugoslavia. He received the support of the local Zagreb organization, led by Josip Broz Tito and Andrija Hebrang. In April, after conferring with Moscow, the Comintern replaced the Central Committee with a temporary leadership in and call on party members to liquidate factionalism. Convoked in this atmosphere, the 4th party congress, held at Dresden in November 1928, saw sharp criticism of the factions, and especially of Marković, who submitted to party discipline and called upon to the Belgrade party to return to party discipline. The congress reaffirmed the centralism principles and demanded that the leadership must be composed of industrial workers educated in the spirit of Leninism. Jovan Mališić was elected political secretary and Đuro Đaković organizational secretary. The congress also predicted an imminent bourgeois revolution, adopted the Comintern's theory of Social fascism, which regarded social democracy as a form of fascism, and reaffirmed the policy of breaking up Yugoslavia. Both the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and the Comintern would support these views until 1935.

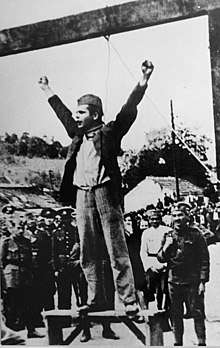

Armed revolt of 1929

On 6 January 1929, King Alexander dispensed with the constitution and introduced a royal dictatorship. The Communist party, encouraged by the Dresden congress, in response called upon workers and peasants to start an armed revolt, considerably overestimating their influence. The majority of Communists observed this appeal but their actions remained isolated and only resulted in an increase of repression by the government: the top leaders of the Young Communist League and of the party, including Đuro Đaković, were killed, numerous members arrested and the party's organization destroyed. In April 1930, the Central Committee moved to Vienna and lost contact with the remaining organizations in the country.

Reconstruction of the party

The experience of the failed revolt helped the Communist Party of Yugoslavia to gradually liberate itself from ideological concepts, sectarianism and the dictate of the Comintern. After 1932, the party began reconstructing its cadres, who could work independently from their superiors in exile. The parliamentary crisis also led to numerous intellectuals joining the Marxist movement. Membership increased from 300 in January 1932 to almost three thousand in December 1934, when the Central Committee finally reestablished contact with the organization inside the country.

At the 4th state conference, held at Ljubljana, in December 1934, the party still clung to the concept of breaking up Yugoslavia and demanded the liberation of Montenegro from Serbian occupation — despite the opposition of Montenegrin Communists against such a declaration. However, the year 1935 saw the reversal of that position: In June, the Central Committee no longer insisted on a division of Yugoslavia but emphasized each nation's right to self-determination, which could be implemented within the framework of a federative Yugoslavia. In August, the party (in conjunction with the Comintern) adopted a plan for a preservation of reconstructed and federalized Yugoslavia under the slogan "Weak Serbia — Strong Yugoslavia".

In the same year, Yugoslavia's Communists also followed the Comintern, when it abandoned the theory of social fascism in favor of a popular front in cooperation with Social Democrats.

Under the conditions of Yugoslavia, such a cooperation helped to break the limitations of illegality and sped up the organizational reconstruction of the party, but also made differences between the leadership in exile and the party in the country more visible. The Central Committee therefore decided in mid-1935 to create a National Bureau (Zemaljski biro) to lead the Party from within the country. Some voices demanded a return of the Central Committee but the large numbers of party members living as political emigrants and the difficulties in running such a stretched party prevented this.

The party's increased activity provoked the authorities to sharp measures and during 1936 about two thousand members were arrested, including most of the members of the National Bureau and many regional leaders and some members of the Central Committee. The Comintern, during consultations in Moscow in August, severely criticized the Yugoslavian leadership and decided to nominate a new leadership and transfer the Central Committee's seat back inside the country.

In November, the leadership was installed with Milan Gorkić as general secretary and Josip Broz as organizational secretary, and in December Broz and other leaders returned to Yugoslavia, where they pursued an anti-fascist policy and initiated a campaign for solidarity with Spanish republicans, which channeled help through the Paris branch of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

Those leaders remaining in Moscow were hit by Stalin's Great Purge, in which many party members were arrested and shot, including the most prominent former leaders of Yugoslavia's Communists: Filip Filipović, Sima Marković, Kosta Novaković, as well as the current general secretary Milan Gorkić, who was deposed and shot in 1937.

Tito's early leadership

The party work was further hampered by factional struggles within the Paris branch, irregular contacts with the Comintern and the cessation of financial aid and the unclear position of the party's representative within the country, Josip Broz. However, Josip Broz (using the pseudonyms of "Walter" and "Tito") was able to unite the party and won the confidence of the Comintern. In May 1938, he set up a temporary leadership inside the country. In August he went to Moscow, through the mediation of Georgi Dimitrov, leader of the Bulgarian Communists, reached an agreement with the Comintern. Tito was authorized to reform the Central Committee within the country, which was accomplished in March 1939 with Tito as general secretary. Tito succeeded in removing the centers of "factionalism" and also lessened the party's financial problems.

The party was also faced with the controversy created by Stalin's purges and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, which both disturbed and alienated many intellectuals. Tito responded by trying to focus on Yugoslavian issues. Such controversy however gradually ceased due to the independent policy towards the Comintern.

With World War II on the horizon, the issue of war became prominent. Yugoslavian Communists accepted the Comintern's evaluation of the "imperialistic character of war" but at the same time insisted on the right of a country to defend itself against aggression.

Economic difficulties and political oppression strengthened the Communist party's appeal; prompting the government to respond with a crack-down on trade-unions in December 1939.

After various regional party conferences analyzing the situation, the 5th state conference was held in October 1940 at Zagreb, which stressed two tasks: the defense of Yugoslavia's independence and the mobilization of the masses in the struggle to solve the most acute internal social and national problems. Regarding the national question, the conference espoused self-determination and cultural autonomy of all peoples, including smaller groups like Albanians, Germans, Hungarians, Romanians.

Invasion and armed resistance

For the South Slav communists were profoundly idealist; they believed in the self-healing properties of society, in the basic regeneration of mankind by works—and in proposing the death of Fascism and the birth of federal democracy with all its concomitants of citizenship and education they saw sufficient stimulus of what they held to be the natural virtues of man. A just society would be its own reward.[4]

In March 1941, after a coup d'état with British support, a group of military officers ousted the pro-Axis Prince Regent Paul and declared the 17-year-old King Peter II of age. In April 1941, Nazi Germany invaded Yugoslavia and quickly defeated the Yugoslav army. The Communist Party decided to organize resistance against the invaders and on 10 April set up a war committee in Zagreb to prepare a war for "national and social liberation".

When Hitler began his invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June, the Communists considered the moment opportune and issued a proclamation calling to the nations of Yugoslavia to resistance. Assisted by the British and the Americans, the Communist-led Partisans used guerrilla tactics to establish territories under their control, where they also introduced elements of socialist revolution, and used propaganda to popularize their aims. At the end of the Yugoslav People's Liberation War in 1945, the Partisans consisted of 800,000 soldiers under the leadership of 14,000 members of the Communist party.

Ruling party of Socialist Yugoslavia

The other parties formed before the war were banned by the Communists. Eight of them entered the coalition with the Communists and founded the People's Front of Yugoslavia (Narodna fronta Jugoslavije), while the Democratic Party of Milan Grol boycott the first post-war elections of 1945 because the elections were held under undemocratic conditions.

The elections were held in the form of a referendum: the People's Front candidate list received 91% of the vote while the option of "no list" won 9%. Yugoslavia became a republic and the other parties were banned. The People's Front (later called the Socialist Alliance of Working People of Yugoslavia, Socijalistički Savez Radnog Naroda Jugoslavije) remained open to those who did not consider themselves to be communists, such as members of the clergy.

In 1948, the party held its fifth Congress. The meeting was held shortly after Stalin accused Tito of being a nationalist and moving to the right branding his heresy Titoism. This resulted in a break with the Soviet Union known as the Informbiro period. Initially the Yugoslav communists, despite the break with Stalin, remained as hard line as before but soon began to pursue a policy of independent socialism that experimented with self-management of workers in state-run enterprises, with decentralization and other departures from the Soviet model of a Communist state.

Under the influence of reformers such as Boris Kidrič and Milovan Đilas, Yugoslavia experimented with ideas of workers self-management where workers influenced the policies of the factories in which they worked and shared a portion of any surplus revenue. This resulted in a change in the party's role in society from holding a monopoly of power to being an ideological leader. As a result, the party name was changed to the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (Savez komunista Jugoslavije, SKJ) in 1952 during its sixth Congress. Likewise, the names of the regional branches were changed accordingly. LCY consisted of the following regional bodies:

- League of Communists of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- League of Communists of Croatia

- League of Communists of Macedonia

- League of Communists of Montenegro

- League of Communists of Serbia

- League of Communists of Slovenia

Dissidents

The Communists had a number of dissidents within its ranks at various periods:

- From 1948 to 1953 during the conflict with Stalin, cf. Informbiro, a number of party members were accused of being pro-Moscow and jailed at Goli Otok.

- Adil Zulfikarpašić, post-war federal Minister of Trade, was in self-imposed exile between 1946 and 1990.

- In 1954, Milovan Đilas was expelled from the party due to his criticisms and his proposals for a multi-party system with a decentralized economy.

- Aleksandar Ranković argued for a highly centralized system more akin to the Soviet model and was expelled from the party in 1966.

- In the course of the Croatian spring of 1971, some of the Croatian party members were disciplined due to accusations of liberalism and nationalism, along with Serbian communists accused of liberalism. Many of their ideas were ultimately adopted in the new 1974 Yugoslav Constitution.

- The Praxis School — a Marxist humanist philosophical movement that originated in Zagreb and Belgrade. Its members were critical towards the version of self-management socialism implemented by the LCY and were removed from their university jobs for their views.

Crisis and dissolution

In the 1960s, the centralized command structure of the League of Communists began to be dismantled with the fall of the hardline OZNA and UDBA chief Aleksandar Ranković in 1966,[5] culminating in the social and political movements that would lead to the de-centralized and regionalized Federal Yugoslavia of the Constitution of 1974.

After Tito's death in 1980 the party adopted a collective leadership model, with the party presidency rotating annually. The party's influence declined and the party moved to a federal structure giving more power to party branches in Yugoslavia's constituent republics. Party membership continued to grow reaching two million in the mid-1980s but membership was considered less prestigious than in the past.

Slobodan Milošević became President of the League of Communists of Serbia in 1987 and combined certain Serbian nationalist ideologies with opposition to liberal reforms. The growing rift among the branches of the Communist Party and their respective republics came to a head at the LCY's 14th Congress, held in January 1990. The LCY renounced its monopoly of power, and agreed to allow opposition parties to take part in elections. However, rifts between Serbian and Slovenian Communists led the LCY to dissolve into different parties for each republic.[6]

The Communist associations in each republic shortly changed their names to Socialist or Social-Democratic parties, transmuting into movements which were left-oriented, but no longer strictly communist.

The remnants of the local branches were transformed:

- the League of Communists of Serbia in 1990 into the Socialist Party of Serbia

- the League of Communists of Croatia in 1990 into the Party of Democratic Changes of Croatia (later merged in 1994 with the Social Democrats of Croatia and renamed party to Social Democratic Party of Croatia)

- the League of Communists of Macedonia in 1990 into the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia

- the League of Communists of Slovenia in 1990 into the Party of Democratic Reforms of Slovenia (in 1993 with smaller extra-parliamentary parties to become the United List of Social Democrats, renamed to Social Democrats in 2005)

- the League of Communists of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1991 into the Social Democratic Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- the League of Communists of Montenegro in 1991 into the Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro

Party leaders

Ethnic composition

| Nationality | Total members | Percent of membership | Percent of total population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serb | 541,526 | 51.77 | 42.08 |

| Croat | 189,605 | 18.13 | 23.15 |

| Slovene | 70,516 | 6.74 | 8.57 |

| Macedonian | 67,603 | 6.46 | 5.64 |

| Montenegrin | 65,986 | 6.31 | 5.24 |

| Muslim | 37,433 | 3.58 | 5.24 |

| Albanian | 31,780 | 3.04 | 4.93 |

| Hungarian | 12,683 | 1.21 | 2.72 |

| Others | 28,886 | 2.76 | 4.90 |

| Total | 1,046,018 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Notes

- Serbo-Croatian: Савез комуниста Југославије (СКЈ), Savez komunista Jugoslavije (SKJ)

Slovene: Zveza komunistov Jugoslavije

Macedonian: Сојуз на комунистите на Југославија, Sojuz na komunistite na Jugoslavija - Serbo-Croatian: Комунистичка партија Југославије (КПЈ), Komunistička partija Jugoslavije (KPJ)

Slovene: Komunistična partija Jugoslavije

Macedonian: Комунистичка партија на Југославија, Komunistička partija na Jugoslavija

References

- Ramet 2006, pp. 172–173.

- Silvio Pons; Robert Service (2012). A Dictionary of 20th-Century Communism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15429-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ""Republika"". www.yurope.com. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- Basil Davidson: Partisan Picture

- The Specter of Separatism, TIME Magazine, February 07, 1972

- Rome Tempest (January 23, 1990). "Communists in Yugoslavia Split Into Factions". Los Angeles Times.

- Tomasevich, Jozo; Vucinich, Wayne S. (1969). Contemporary Yugoslavia: Twenty Years of Socialist Experiment. University of California Press. p. 256.

Further reading

- Geoffrey Swain, "Tito and the Twilight of the Comintern," in Tim Rees and Andrew Thorpe (eds.), International Communism and the Communist International, 1919-43. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to League of Communists of Yugoslavia. |

- Avgust Lešnik, The Development of the Communist Movement in Yugoslavia during the Comintern Period

- History of the SKJ (Serbo-Croatian)