Chechen Republic of Ichkeria

The Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (/ɪtʃˈkɛriə/; Chechen: Nóxçiyn Respublik Içkeri; Russian: Чеченская Республика Ичкерия; abbreviated as "ChRI" or "CRI") was a partially recognized secessionist government of the Checheno-Ingush ASSR. On November 30, 1991 Ingushetia would have an referendum in which the results dictated its separation from the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, joining the Russian Federation instead as a constituent republic.[3]

Chechen Republic (1991–1992) Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (1992–2000) Nóxçiyn Respublik Içkeri Чеченская Республика Ичкерия | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–2000[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

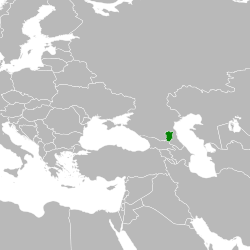

Location of Chechnya | |||||||||||

| Status | Soviet autonomy (1991) Independent state (1991–2000) Government-in-exile (2000–07) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Grozny[lower-alpha 2] | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Chechen · Russian[1] | ||||||||||

| Religion | State secularism[1] (1991–96) Sunni Islam (1996–2000) | ||||||||||

| Government | Republic (1991–96) Islamic republic[2] (1996–2000) | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1991–96 | Dzhokhar Dudayev † | ||||||||||

• 1996–97 | Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev † | ||||||||||

• 1997–2000 | Aslan Maskhadov | ||||||||||

| President-in-exile | |||||||||||

• 2000–05 | Aslan Maskhadov † | ||||||||||

• 2005–06 | Abdul-Halim Sadulayev † | ||||||||||

• 2006–07 | Dokka Umarov | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 1 November 1991 | |||||||||||

• Dissolution of the Soviet Union | 26 December 1991 | ||||||||||

| 11 December 1994 | |||||||||||

• Moscow Peace Treaty signed | 12 May 1997 | ||||||||||

| 1 May 2000[lower-alpha 3] | |||||||||||

• Emirate proclaimed | 31 October 2007 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 2002 | 15,300 km2 (5,900 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 2002 | 1,103,686 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Russian ruble Chechen naxar[lower-alpha 4] | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Chechnya | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Prehistory | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Ancient | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Medieval | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Early modern | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Modern | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

The First Chechen War of 1994–96 resulted in the victory of the separatist forces.[4] After achieving de facto independence from Russia in 1996, the Chechen government failed to establish order.[5] In November 1997 Chechnya was proclaimed an Islamic republic.[6][7] A Second Chechen War began in August 1999 and ended in May 2000, with Chechen rebels continuing attacks as an insurgency.[8]

History

Declaration of Independence

In November 1990, Dzhokhar Dudayev was elected head of the Executive Committee of the unofficial opposition All-National Congress of the Chechen People (NCChP), which advocated sovereignty for Chechnya as a separate republic within the Soviet Union.

The Soviet coup d'état attempt on 19 August 1991 became the spark for the so-called Chechen revolution.[9] On 21 August the NCChP called for the overthrow of the Supreme Soviet of the Chechen-Ingush Republic.[9] In September 1991, NCChP squads seized the local KGB headquarters, and took over the building of the Supreme Soviet.[10] The NCChP declared itself the only legitimate authority in the region.[10] In October 1991, Dudayev was elected president of the Chechen-Ingush Republic.[11] Dudayev, in his new position as president, issued a unilateral declaration of independence on 2 November 1991.[12] Initially, his stated objective was for Checheno-Ingushetia to become a union republic within Russia.[13]

The separatist Interior Minister promised amnesty to any prison inmates who would join pro-independence rallies.[14] Among the prisoners was Ruslan Labazanov, who was serving a sentence for armed robbery and murder in Grozny and later headed a pro-Dudayev militia.[15] As crowds of armed separatists gathered in Grozny, President Yeltsin sought to declare a state of emergency in the region, but his efforts were thwarted by the Russian parliament.[13] An early attempt by Russian authorities to confront the pro-independence forces in November 1991 ended after just three days.[16][17]

In early 1992 Dudayev signed a decree outlawing the extradition of criminals to any country which did not recognize Chechnya.[18] After being informed that the Russian government would not recognize Chechnya's independence, he declared that he would not recognize Russia.[12] Grozny became an organized crime haven, as the government proved unable or unwilling to curb criminal activities.[12]

Dudayev's government created the constitution of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, which was introduced on March 1992.[19] In the same month, armed clashes occurred between pro and anti-Dudayev factions, leading Dudayev to declare a state of emergency.[20] Chechnya and Ingushetia separated on 4 June 1992.[21] Relationship between Dudayev and the parliament deteriorated, and in June 1992 he dissolved the parliament, establishing direct presidential rule.[20]

In late October 1992, federal forces were dispatched to end the Ossetian-Ingush conflict. As Russian troops sealed the border between Chechnya and Ingushetia to prevent arms shipments, Dudayev threatened to take action unless the Russians withdrew.[22] Russian and Chechen forces mutually agreed to a withdrawal, and the incident ended peacefully.[23]

Clashes between supporters and opponents of Dudayev occurred in April 1993. The President fired Interior Minister Sharpudin Larsanov after he refused to disperse the protesters.[24] The opposition planned a no-confidence referendum against Dudayev for 5 June 1993.[25] The government deployed army and riot police to prevent the vote from taking place, leading to bloodshed.[25]

After staging another coup attempt in December 1993, the opposition organized a Provisional Council as a potential alternative government for Chechnya, calling on Moscow for assistance.

First war

The general feeling of lawlessness in Chechnya increased during the first seven months in 1994, when four hijacking accidents occurred, involving people trying to flee the country.[26] In May 1994 Labazanov changed sides, establishing the anti-Dudayev Niyso Movement.[15] In July 1994, 41 passengers aboard a bus near Mineralniye Vody were held by kidnappers demanding $15 million and helicopters.[27] After this incident, the Russian government started to openly support opposition forces in Chechnya.[28]

In August 1994 Umar Avturkhanov, leader of the pro-Russian Provisional Council, launched an attack against pro-Dudayev forces.[29] Dudayev ordered the mobilization of the Chechen military, threatening a jihad against Russia as a response to Russian support for his political opponents.[30]

In November 1994 Avturkanov's forces attempted to storm the city of Grozny, but they were defeated by Dudayev's forces.[31] Dudayev declared his intention to turn Chechnya into an Islamic state, stating that the recognition of sharia was a way to fight Russian 'aggression'.[32] He also vowed to punish the captured Chechen rebels under Islamic law, and threatened to execute Russian prisoners.[33]

The First Chechen War began in December 1994, when Russian troops were sent to Chechnya to fight the separatist forces.[34] During the Battle of Grozny (1994–95), the city's population dropped from 400,000 to 140,000.[35] Most of the civilians stranded in the city were elderly ethnic Russians, as many Chechens had support networks of relatives living in villages who took them in.[35]

Salambek Khadzhiyev was appointed leader of the officially recognized Chechen government in early 1995.[36] The conflict ended after the Russian defeat in the Battle of Grozny of August 1996.[34]

Interwar period (1996–1999)

After the Russian withdrawal crime became rampant, with kidnappings and murders multiplying as rival rebel factions fought for territory.[37] In December 1996 six Red Cross workers were killed, leading most foreign aid workers to leave the country.[37]

Parliamentary and presidential elections took place in January 1997 in Chechnya and brought to power Aslan Maskhadov. The elections were deemed free and fair, but no government recognized Chechnya's independence, except for the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.[38] Ethnic Russian refugees were prevented from returning to vote by threats and intimidation, and Chechen authorities refused to set up polling booths outside the republic.[39]

Maskhadov sought to maintain Chechen sovereignty while pressing Moscow to help rebuild the republic, whose formal economy and infrastructure were virtually destroyed.[40]

In May 1997 the Russia–Chechen Peace Treaty was signed by Maskhadov and Yeltsin.[41] Russia continued to send money for the rehabilitation of the republic; it also provided pensions and funds for schools and hospitals. Most of these transfers were stolen by corrupt Chechen authorities and divided between themselves and favoured warlords.[42] Nearly half a million people (40% of Chechnya's prewar population) have been internally displaced and lived in refugee camps or overcrowded villages.[43] The economy was destroyed. Two Russian brigades were stationed in Chechnya and did not leave.[43] Maskhadov made efforts to rebuild the country and its devastated capital Grozny by trading oil in countries such as the United Kingdom.[44]

Chechnya had been badly damaged by the war and the economy was in shambles.[45] Aslan Maskhadov tried to concentrate power in his hands to establish authority, but had trouble creating an effective state or a functioning economy. As part of the peace negotiations, Maskhadov demanded $260 billion in reparations from Russia, an amount equivalent to 60% of the Russian GDP.[46]

The war ravages and lack of economic opportunities left numbers of armed former guerrillas with no occupation but further violence. Machine guns and grenades were sold openly and legally in Grozny's central bazaar.[47] The years of independence had some political violence as well. On 10 December Mansur Tagirov, Chechnya's top prosecutor, disappeared while returning to Grozny. On 21 June the Chechen security chief and a guerrilla commander fatally shot each other in an argument. The internal violence in Chechnya peaked on 16 July 1998, when fighting broke out between Maskhadov's National Guard force led by Sulim Yamadayev (who joined pro-Moscow forces in the second war) and militants in the town of Gudermes; over 50 people were reported killed and the state of emergency was declared in Chechnya.[48]

Maskhadov proved unable to guarantee the security of the oil pipeline running across Chechnya from the Caspian Sea, and illegal oil tapping and acts of sabotage deprived his regime of crucial revenues and agitated his allies in Moscow. In 1998 and 1999 Maskhadov survived several assassination attempts, which he blamed on foreign intelligence services.[49] The attacks were seen as more likely to originate from within Chechnya, as the Kremlin deemed Maskhadov an acceptable negotiating partner for the Chechen conflict.[49]

In December 1998, the supreme Islamic court of Chechnya suspended the Chechen Parliament, asserting that it did not conform to the standards of sharia.[50] After the Chechen Vice-President Vakha Arsanov defected to the opposition, Maskhadov abolished his post, leading to a power struggle.[51] In February 1999 President Maskhadov removed legislative powers from the parliament and convened an Islamic State Council.[52] At the same time several prominent former warlords established the Mehk-Shura, a rival Islamic government.[52] The Shura advocated the creation of an Islamic confederation in the North Caucasus, including the Chechen, Dagestani and Ingush peoples.[53]

On 9 August 1999, Islamist fighters from Chechnya infiltrated Russia's Dagestan region, declaring it an independent state and calling for a jihad until "all unbelievers had been driven out".[54] This event prompted Russian intervention, and the beginning of the Second Chechen War. As more people escaped the war zones of Chechnya, President Maskhadov threatened to impose sharia punishment on all civil servants who moved their families out of the republic.[55]

Second war and postwar period

Since the fall of Grozny in 2000 some of the Ichkerian government was based in exile, including in Poland and the United Kingdom. On 23 January 2000 a diplomatic representation of Ichkeria was based in Kabul during the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. In June 2000 Akhmed Kadyrov was appointed as head of the official administration of Chechnya.[56]

On 31 October 2007, the separatist news agency Chechenpress reported that Dokka Umarov had announced the Caucasus Emirate and declared himself its Emir. He integrated the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria as Vilayat Nokhchicho. This change of status was rejected by some Chechen politicians and military leaders who continue to support the existence of the republic. Since November 2007, Akhmed Zakayev says he is now the Prime Minister of Ichkeria's government in exile.

Military

Dudayev spent the years from 1991 to 1994 preparing for war, mobilizing men aged 15–55 and seizing Russian weapons depots. The Chechen National Guard counted 10,000 troops in December 1994, rising to 40,000 soldiers by early 1996.[57]

Major weapons systems were seized from the Russian military in 1992, and on the eve of the First Chechen War they included 23 air defense guns, 108 APC/tanks, 24 artillery pieces, 5 MiG-17/15, 2 Mi-8 helicopters, 24 multiple rocket launchers, 17 surface to air missile launchers, 94 L-29 trainer aircraft, 52 L-39 trainer aircraft, 6 An-22 transport aircraft, 5 Tu-134 transport aircraft.[57]

Politics

Since the declaration of independence in 1991, there has been an ongoing battle between secessionist officials and federally appointed officials. Both claim authority over the same territory.

In late 2007, the President of Ichkeria, Dokka Umarov, declared that he had renamed the republic to Noxçiyc̈ó and converted it into a province of the much larger Caucasus Emirate, with himself as Emir. This change was rejected by some members of the former Chechen government-in-exile.

Foreign relations

Ichkeria was a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. Former president of Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, deposed in a military coup of 1991 and a leading participant in the Georgian Civil War, recognised the independence of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria in 1993.[58]

Diplomatic relations with Ichkeria were also established by the partially recognized Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan under the Taliban government on 16 January 2000. This recognition ceased with the fall of the Taliban in 2001.[59] However, despite Taliban recognition, there were no friendly relations between the Taliban and Ichkeria—Maskhadov rejected their recognition, stating that the Taliban were illegitimate.[60] In June 2000, the Russian government claimed that Maskhadov had met with Osama bin Laden, and that the Taliban supported the Chechens with arms and troops.[61] In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, the Bush administration called on Maskhadov to cut all links with the Taliban.[62]

Ichkeria also received vocal support from the Baltic countries, a group of Ukrainian nationalists and Poland; Estonia once voted to recognize, but the act never was consummated due to pressure applied by both Russia and the pro-Russian elements within the EU.[60][63][64] Dudayev also had contacts with Islamist movements and guerrillas in Jordan, Lebanon and Iran.[65]

Human rights

War crimes

Throughout the span of the First Chechen War several war crimes were committed on both sides. Infamous among them was the Samashki massacre, which the United Nations Commission on Human Rights had this to say regarding the massacre:

It is reported that a massacre of over 100 people, mainly civilians, occurred between 7 and 8 April 1995 in the village of Samashki, in the west of Chechnya. According to the accounts of 128 eye-witnesses, Federal soldiers deliberately and arbitrarily attacked civilians and civilian dwellings in Samashki by shooting residents and burning houses with flame-throwers. The majority of the witnesses reported that many OMON troops were drunk or under the influence of drugs. They wantonly opened fire or threw grenades into basements where residents, mostly women, elderly persons and children, had been hiding.[66]

Kidnappings

Kidnappings, robberies, and killings of fellow Chechens and outsiders weakened the possibilities of outside investment and Maskhadov's efforts to gain international recognition of its independence effort. There was some evidence that the Federal Security Service was behind the kidnappings and financed them.[67][68]

Kidnappings became common in Chechnya, procuring over $200 million during the three year independence of the chaotic fledgling state,[69] but victims were rarely killed.[70] Kidnappers would at times mutilate their captives and send video recordings to their families, to encourage the payment of ransoms.[71]

Some of the kidnapped were supposedly sold into indentured servitude to Chechen families. They were openly called slaves and had to endure starvation, beating, and often maiming according to Russian sources.[42][72][73][74] In 1998, 176 people had been kidnapped, and 90 of them had been released during the same year according to official accounts. There were several public executions of criminals.[75][76]

In 1998, four western engineers working for Granger Telecom were abducted and beheaded after a failed rescue attempt.[77] Gennady Shpigun, the Interior Ministry liaison to Chechen officials, was kidnapped in March 1999 as he was leaving Grozny Airport; his remains were found in Chechnya in March 2000.[78]

President Maskhadov started a major campaign against hostage-takers, and on 25 October 1998, Shadid Bargishev, Chechnya's top anti-kidnapping official, was killed in a remote controlled car bombing. Bargishev's colleagues then insisted they would not be intimidated by the attack and would go ahead with their offensive. Other anti-kidnapping officials blamed the attack on Bargishev's recent success in securing the release of several hostages, including 24 Russian soldiers and an English couple.[79] Maskhadov blamed the rash of abductions in Chechnya on unidentified "outside forces" and their Chechen henchmen, allegedly those who joined Pro-Moscow forces during the second war.[80]

Sharia

After the First Chechen War, the country won de facto independence from Russia, and Islamic courts were established.[81] In September 1996 a Sharia-based criminal code was adopted, which included provisions for banning alcohol and punishing adultery with death by stoning.[82] Sharia was supposed to apply to Muslims only, but in fact it was also applied to ethnic Russians who violated Sharia provisions.[82] In one of the first rulings under sharia law, in January 1997 an Islamic court ordered the payment of blood money to the family of a man who was killed in a traffic accident.[81] In November 1997 the Islamic dress code was imposed on all female students and civil servants in the country.[83] In December 1997, the Supreme Sharia Court banned New Year celebrations, considering them "an act of apostasy and falsity".[84]

Conceding to an armed and vocal minority movement in the opposition led by Movladi Udugov, in February 1999, Maskhadov declared The Islamic Republic of Ichkeria, and the Sharia system of justice was introduced. Maskhadov hoped that this would discredit the opposition, putting stability before his own ideological affinities. However, according to former Foreign Minister Ilyas Akhmadov, the public primarily supported Maskhadov, his Independence Party, and their secularism. This was exemplified by the much greater numbers in political rallies supporting the government than those supporting the Islamist opposition.[85] Akhmadov notes that the parliament, which was dominated by Maskhadov's own Independence Party, issued a public statement that President Maskhadov did not have the constitutional authority to proclaim sharia law, and also condemning the opposition for "undermining the foundations of the state".[86]

Minorities

Ethnic Russians made up 29% of the Chechen population before the war,[87] and they generally opposed independence.[14] Due to the mounting anti-Russian sentiment following the declaration of independence and the fear of an upcoming war, by 1994 over 200,000 ethnic Russians decided to leave the independence-striving republic.[88][89]

Ethnic Russians left behind faced constant harassment and violence.[90] The separatist government acknowledged the violence, but did nothing to address it, blaming it on Russian provocateurs.[90] Russians became soft target for criminals, as they knew the Chechen police would not intervene in their defence.[90] The start of the First Chechen War in 1994 and the first bombing of Grozny created a second wave of ethnic Russian refugees. By the end of the conflict in 1996, the Russian community had nearly vanished.[90]

Chechnya was not the only area of the former Soviet Union where the number of the Russian minority decreased after the collapse. In-fact, most subjects that gained independence through this saw a big decrease among the Russian diaspora in their country.[91]

See also

- Secession in Russia

- Borz

- Chechenpress

- Caucasus Emirate

- Dokka Umarov

- History of Chechnya

- List of unrecognized countries

- Shamil Basayev

References

- In exile until 2007.

- Renamed Ƶovxar-Ġala in 1996.

- In exile until 2007.

- Planned; never entered circulation.

- "The Constitution of Chechen Republic Ichkeria". Waynakh Online. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- "Конституция Чеченской Республики » Zhaina — Нахская библиотека". zhaina.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- Evloev, Musa. "Как принималась Конституция Республики Ингушетия".

- "Still growling". The Economist. 22 January 1998. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Chechen president cracks down on crime". BBC News. 20 July 1998. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Chechnya's chop-chop justice". The Economist. 18 September 1997. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Chechnya proclaimed Islamic republic". UPI. 5 November 1997. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Chechnya profile". BBC News. 11 August 2015. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Yevsyukova, Mariya (1995). "The Conflict Between Russia And Chechnya - Working Paper #95-5(1)". University of Colorado, Boulder. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Первая война". Коммерсантъ. 13 December 2014. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Dobbs, Michael (29 October 1991). "Ethnic Strife Splintering Core of Russian Republic". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Defiance of the wolf baying at Yeltsin's door". The Guardian. 8 September 1994. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013.

- Trevelyan, Mark (13 November 1991). "Breakaway leader challenges Russia". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Bohlen, Celestine (12 November 1991). "Legislators Block Yeltsin Rule of Breakaway Area". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Forces of Rusland Labazanov". Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Hockstader, Lee (12 December 1994). "Russia Pours Troops Into Breakaway Region". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 3 September 2000. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Steele, Jonathan (11 November 1991). "Yeltsin fails to bring rebels to heel". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Baranovski, I. (12 June 1992). "Mob Rule in Moscow". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Pike, John. "Chechen Leadership In Exile Seeks To Salvage Legitimacy". Archived from the original on 17 February 2008.

- "1992-1994: Independence in all but name". The Telegraph. 1 January 2001. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Bombers threaten Ingush Duma hopeful". UPI. 1 July 2000. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Schmemann, Serge (11 November 1992). "Russian Troops Arrive As Caucasus Flares Up". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Jenkinson, Brett C. (2002). "Tactical Observations From The Grozny Combat Experience" (PDF). United States Military Academy, West Point. p. 29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Chechens in bloody protest". The Independent. 26 April 1993. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Armed standoff in breakaway Russian province". UPI. 17 June 1993. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Smith, Duane “Mike”; Hodges, Frederick “Ben”. "War as a Continuation of Policy". Archived from the original on 10 December 2017.

- "Russians show photos that 'prove Chechen beheadings'". The Independent. 2 August 1994. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Russia loses patience with Chechen rebels". The Independent. 1 August 1994. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Efron, Sonni (3 August 1994). "Opposition Reports Toppling Chief of Breakaway Russian Republic". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015.

- Meek, James (12 August 1994). "Dudayev threatens holy war". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "The savagery of war: A soldier looks back at Chechnya". The Independent. 10 November 2007. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "President of Chechnya Backs Islamic State". The New York Times. 21 November 1994. Archived from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Airstrike hits Chechen separatist region". UPI. 29 November 1994. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Russian troops begin pullout in Chechnya". CNN. 25 August 1996. Archived from the original on 29 April 2005.

- Erlanger, Steven (9 April 1995). "In Fallen Chechen Capital, Medical Care Is in Ruins". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Erlanger, Steven (29 March 1995). "Grozny Journal; Picking Up, After Guns Have Done Their Worst". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Stanley, Alessandra (24 January 1997). "Chechen Voters' Key Concerns: Order and Stability". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Reynolds, Maura (28 September 2001). "Envoys of Russia, Chechnya Discuss Options for Peace". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Little Hope in Poll for Ethnic Russians". The Moscow Times. 23 January 1997. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Freedomhouse.org". Archived from the original on 8 February 2011.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Stanley, Alessandra (13 May 1997). "Yeltsin Signs Peace Treaty With Chechnya". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010.

- Leon Aron. Chechnya, New Dimensions of the Old Crisis Archived 12 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine . AEI, 1 February 2003

- Alex Goldfarb and Marina Litvinenko. "Death of a Dissident: The Poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko and the Return of the KGB." Free Press, New York, 2007. Archived 29 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-1-4165-5165-2.

- London Sunday Times on Mashkadov visit Archived 12 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- The International Spectator 3/2003, The Afghanisation of Chechnya, Peter Brownfeld Archived 11 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Habeas corpus". The Economist. 21 August 1997. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "War racketeers plague Chechnya". BBC News. 14 December 2004. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Further emergency measures in Chechnya Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Chechen leader survives assassination attempt". BBC News. 23 July 1998. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- France-Presse, Agence (25 December 1998). "A Chechen Islamic Ruling". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Islamist vice-president defies Chechen leader". BBC News. 7 February 1999. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Chechnya power struggle". BBC News. 9 February 1999. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Russia's violent southern rim". The Economist. 25 March 1999. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Dagestan moves to state of holy war". The Independent. 11 August 1999. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Uzelac, Ana (7 October 1999). "In ruins of one war, Grozny prepares for the second". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Russia appoints Chechen leader". BBC News. 12 June 2000. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Lutz, Raymond R. (April 1997). "Russian Strategy In Chechnya: a Case Study in Failure". Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- in 1993, ex-President of Georgia Zviad Gamsakhurdia recognized Chechnya ` s independence.. Archived 21 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine,

- Are Chechens in Afghanistan? – By Nabi Abdullaev, 14 December 2001 Moscow Times Archived 7 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Kullberg, Anssi. "The Background of Chechen Independence Movement III: The Secular Movement". The Eurasian politician. 1 October 2003

- "What Moscow wants from 'summit'". Christian Science Monitor. 2 June 2000. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Chechens in talks as deadline passes". BBC News. 27 September 2001. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Kari Takamaa and Martti Koskenneimi. The Finnish Yearbook of International Law. p147

- Kuzio, Taras. "The Chechen crisis and the 'near abroad'". Central Asian Survey, Volume 14, Issue 4 1995, pages 553–572

- Boudreaux, Richard (9 February 1995). "Faith Fuels Chechen Fighters". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- The situation of human rights in the Republic of Chechnya of the Russian Federation - Report of the Secretary-General UNCHR Archived February 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Chechnya's hard path to statehood". BBC News. 1 October 1999. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "J. Littell – The Security Organs of the Russian Federation. A Brief History 1991-2005". Post-Soviet Armies Newsletter. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Tishkov, Valery. Chechnya: Life in a War-Torn Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. Page 114.

- Four Western hostages beheaded in Chechnya Archived 3 December 2002 at the Wayback Machine

- Dixon, Robyn (18 September 2000). "Chechnya's Grimmest Industry". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- RF Ministry of Justice information. Chechnya violates basic legal norms Archived 14 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 8 December 1999

- RFERL, Russia: RFE/RL Interviews Chechen Field Commander Umarov Archived 14 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 27 July 2005; Doku Umarov who was the head of the Security Council of Ichkeria in 1997–1999 accused Movladi Baisarov and one of Yamadayev brothers of engaging in slave trade in the inter-war period

- Соколов-Митрич, Дмитрий (2007). Нетаджикские девочки, нечеченские маьлчики (in Russian). Moscow: Яуза-Пресс. ISBN 978-5-903339-45-7. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011.

- Document Information | Amnesty International Archived 21 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- "Latest News – MFA of Latvia". Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "Hostages 'beheaded at roadside'". BBC News. 9 December 1998. Archived from the original on 1 March 2015.

- Wines, Michael (15 June 2000). "Russia Says Remains Are Those Of Envoy Abducted in Chechnya". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- The Michigan Daily Online Archived 30 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Police tried to silence GfbV – Critical banner against Putin´s Chechnya policies wars Archived 12 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Chechen court applies Islamic law". The Independent. 3 January 1997. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Stanley, Alessandra (1997). "Islam Gets the Law and Order Vote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Islamic dress code for Chechnya". BBC News. 12 November 1997. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Chechen Islamic court bans all New Year celebrations". BBC News. 11 December 1997. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Akhmadov, Ilyas. The Chechen Struggle: Independence Won and Lost. Page 144. "The size of the rallies indicated that the public was behind Maskhadov and the secular state... and, in autumn, that they [the opposition] could not summon public support either on the street or in the parliament."

- Akhmadov, Ilyas. The Chechen Struggle: Independence Won and Lost. Page 143.

- Bristol, Lela; Gutterman, Steve (22 November 1991). "Soviet Union: Mother Russia". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Goldberg, Carey; Efron, Sonni (30 December 1994). "Russia Bombs Chechen Oil Plant; Dudayev Seeks Talks". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017.

200,000 ethnic Russians have also fled Chechnya in the three years since it declared a unilateral independence [...] These people, propelled from their homes by growing anti-Russian sentiment, will probably never go back and will require resettlement

- Smith, Sebastian (23 January 1997). "Little Hope in Poll for Ethnic Russians". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Smith, Sebastian (2006). Allah's Mountains: The Battle for Chechnya, New Edition. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 133–134. ISBN 9781850439790.

- "Population Change in the Former Soviet Republics Between 1989 & 2018".

External links

- Official website of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, archived June 2000