Tiananmen Square

Tiananmen Square or Tian'anmen Square (天安门, Pinyin: Tiān'ānmén; Wade–Giles: Tʻien1-an1-mên2) is a city square in the centre of Beijing, China, named after the Tiananmen ('Gate of Heavenly Peace') located to its north, separating it from the Forbidden City. The square contains the Monument to the People's Heroes, the Great Hall of the People, the National Museum of China, and the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong. Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China in the square on October 1, 1949; the anniversary of this event is still observed there.[1] Tiananmen Square is within the top ten largest city squares in the world (440,500 m2 – 880×500 m or 109 acres – 960×550 yd).[2] It has great cultural significance as it was the site of several important events in Chinese history.

| Tian'anmen Square | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Groups of people wander around Tian'anmen Square in the late afternoon. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 天安门广场 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 天安門廣場 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Tiān'ānmén Guǎngchǎng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡝᠯᡥᡝ ᠣᠪᡠᡵᡝ ᡩᡠᡴᠠ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | elhe obure duka | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Outside China, the square is best known for the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests that ended with a military crackdown, which is also known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre or June Fourth Massacre.[3][4][5]

History

The Tiananmen ("Gate of Heavenly Peace"), a gate in the wall of the Imperial City, was built in 1415 during the Ming dynasty. In the 17th century, fighting between Li Zicheng's rebel forces and the forces of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty caused heavy damage to, or even destroyed, the gate. Tiananmen Square was designed and built in 1651, and was enlarged fourfold in the 1950s.[6][7]

Near the centre of the square stood the "Great Ming Gate", the southern gate to the Imperial City, renamed "Great Qing Gate" during the Qing dynasty, and "Gate of China" during the Republican era. Unlike the other gates in Beijing, such as the Tiananmen and the Zhengyangmen, this was a purely ceremonial gateway, with three arches but no ramparts, similar in style to the ceremonial gateways found in the Ming tombs. This gate had a special status as the "Gate of the Nation", as can be seen from its successive names. It normally remained closed, except when the Emperor passed through. Commoner traffic was diverted to side gates at the western and eastern ends of the square, respectively. Because of this diversion in traffic, a busy marketplace, called "Chess Grid Streets", was developed in the big, fenced square to the south of this gate.

In 1860, during the Second Opium War, when British and French troops invaded Beijing, they pitched camp near the gate and briefly considered burning down the gate and the entire Forbidden City. They decided ultimately to spare the Forbidden City and instead burn down the Old Summer Palace. The Xianfeng Emperor eventually agreed to let the foreign powers barrack troops – and later establish diplomatic missions – in the area, hence there was the Legation Quarter immediately to the east of the square. When the forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance besieged Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, they badly damaged the office complexes and burnt down several ministries. After the Boxer Rebellion ended, the area became a space for the foreign powers to assemble their military forces.

In 1954, the Gate of China was demolished, allowing for the enlargement of the square. In November 1958, a major expansion of Tiananmen Square started, which was completed after only 11 months, in August 1959. This followed the vision of Mao Zedong to make the square the largest and most spectacular in the world, and intended to hold over 500,000 people. In that process, a large number of residential buildings and other structures have been demolished.[8] On its southern edge, the Monument to the People's Heroes has been erected. Concomitantly, as part of the Ten Great Buildings constructed between 1958 and 1959 to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of the People's Republic of China (PRC), the Great Hall of the People and the Revolutionary History Museum (now the National Museum of China) were erected on the western and eastern sides of the square.[8]

For the first decade of the PRC, each National Day (October 1) was marked by a large military parade in Tiananmen Square, in conscious emulation of the annual Soviet celebrations of the Bolshevik Revolution. After the disaster of the Great Leap Forward, the CCP decided to cut costs and have only smaller annual National Day celebrations in addition to a large celebration with a military parade every 10 years. However, the chaos of the Cultural Revolution almost prevented such an event from taking place on National Day, 1969, which did take place (parades were also held there in 1966 and 1970). Ten years later, in 1979, the CCP again decided against a large scale celebration, coming at a time when Deng Xiaoping was still consolidating power and China had suffered a rebuff in a border war with Vietnam early in the year. By 1984, with the situation much improved and stabilized, the PRC held a military parade for the first time since 1959. The aftermath of the Tiananmen Square massacre prevented any such activities in October 1989, but military parades have been held in 1999 and 2009, on the 50th and 60th anniversaries of the PRC's founding. On May 8, 2015, a military parade was also held to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II.

In 1971, large portraits of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Sun Yat-sen, and Mao Zedong were erected in the square, painted by artist Ge Xiaoguang, who is also responsible for producing the famous portrait of Mao that hangs over the Gate of Heavenly Peace. In 1980, with the downgrading of political ideology following Mao's death, the portraits were taken down and thenceforth only brought out on Labor Day (May 1) and National Day. In 1988, the CCP leadership decided to display only the portraits of Sun and Mao on national holidays.

The year after Mao's death in 1976, a mausoleum was built near the site of the former Gate of China, on the main north–south axis of the square. In connection with this project, the square was further increased in size to become fully rectangular and being able to accommodate 600,000 people.[8]

The urban context of the square was altered in the 1990s with the construction of National Grand Theatre in its vicinity and the expansion of the National Museum.[8]

Panorama

Configuration

.jpg)

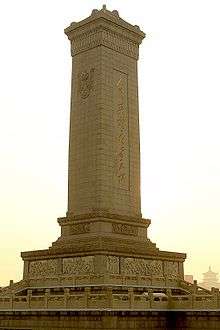

Used as a massive meeting place since its creation, its flatness is contrasted by the 38-metre (125 ft) high Monument to the People's Heroes, and the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong.[6] The square lies between two ancient, massive gates: the Tiananmen to the north and the Zhengyangmen (better known as Qianmen) to the south. Along the west side of the square is the Great Hall of the People. Along the east side is the National Museum of China (dedicated to Chinese history predating 1919). Erected in 1989, Liberty, a statue representing the western icon holds her torch over the square.[9] Chang'an Avenue, which is used for parades, lies between the Tian'anmen and the square.Trees line the east and west edges of the Square, but the square itself is open, with neither trees nor benches. The square is lit with large lamp posts which are fitted with video cameras. It is heavily monitored by uniformed and plain-clothes police officers.

Events

Tiananmen Square has been the site of a number of political events and student protests.

Perhaps the most notable events are protests during the May Fourth Movement in 1919, the proclamation of the People's Republic of China by Mao Zedong on October 1, 1949, the Tiananmen Square protests in 1976 after the death of Zhou Enlai, and the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 after the death of Hu Yaobang. The latter resulted in military suppression and the deaths of hundreds, if not thousands, of civilian protestors.[10] One of the most famous images that appears during these protests was when a man stood in front of a line of moving tanks and refused to move, which was captured on Chang'an Avenue near the square.

Other notable events include annual mass military displays on each anniversary of the 1949 proclamation until 1 October 1959; the 1984 military parade for the 35th anniversary of the People's Republic of China which coincided with the ascendancy of Deng Xiaoping; military displays and parades on the 50th anniversary of the People's Republic of China in 1999; the Tiananmen Square self-immolation incident in 2001; military displays and parades on the 60th anniversary of the People's Republic of China in 2009, and an incident in 2013 involving a vehicle that plowed into pedestrians.

Access

The square, located in the center of the city, is readily accessible by public transport. Line 1 of the Beijing Subway has stops at Tiananmen West and Tiananmen East, respectively, to the northwest and northeast of the square on Chang'an Avenue. Line 2's Qianmen Station is directly south of the square.

City bus routes 1, 5, 10, 22, 52, 59, 82, 90, 99, 120, 126, 203, 205, 210 and 728 stop north of the Square. Buses 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 17, 20, 22, 44, 48, 53, 54, 59, 66, 67, 72, 82, 110, 120, 126, 301, 337, 608, 673, 726, 729, 901, 90, 特2, 特4 and 特7 stop to the south of the Square.

The square is normally open to the public, but remains under heavy security. Before entry, visitors and their belongings are searched, a common practice at many Chinese tourist sites, although the square is somewhat unusual in that domestic visitors often have their identification documents checked and the purpose of their visit questioned. Both plain-clothes and uniformed police officers patrol the area. There are numerous fire extinguishers placed in the area to put out flames should a protester attempt self-immolation.

Image gallery

Tiananmen gate to the north of Tiananmen Square

Tiananmen gate to the north of Tiananmen Square National Museum of China on the east side of the Square

National Museum of China on the east side of the Square The Great Hall of the People on the west side of the Square

The Great Hall of the People on the west side of the Square Zhengyangmen Gate Tower marking the south end of Tiananmen Square

Zhengyangmen Gate Tower marking the south end of Tiananmen Square Monument to the People's Heroes and the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong occupy the center of the Square

Monument to the People's Heroes and the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong occupy the center of the Square

Mausoleum of Mao Zedong

Mausoleum of Mao Zedong Monument in front of Mao's Mausoleum on Tiananmen Square

Monument in front of Mao's Mausoleum on Tiananmen Square Students attending the founding ceremony of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949.

Students attending the founding ceremony of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949. A temporary monument in Tiananmen Square marking the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2011

A temporary monument in Tiananmen Square marking the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2011 National mourning on May 19, 2008 for the victims of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake

National mourning on May 19, 2008 for the victims of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake Students gather for a demonstration in Tiananmen Square, ca. 1917–1919.

Students gather for a demonstration in Tiananmen Square, ca. 1917–1919.

References

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed

- "Tiananmen Square". Britannica. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- Miles, James (2 June 2009). "Tiananmen killings: Were the media right?". BBC News. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- Wong, Jan (1997) Red China Blues, Random House, p. 278, ISBN 0385482329.

- "Tiananmen Square protest death toll 'was 10,000'". BBC News. 23 December 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Safra, J. (Ed.). (2003). Tiananmen Square. In New Encyclopædia Britannica, The (15th ed., Chicago: Vol. 11). Encyclopædia Britannica INC. p. 752. Britannica Online version

- "Tiananmen Square". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- Li, M. Lilliam; Dray-Novey, Alison J.; Kong, Haili (2007) Beijing: From Imperial Capital to Olympic City, Palgrave, ISBN 978-1-4039-6473-1

- Roberts, J. M. (John Morris), 1928-2003. (1993). History of the world. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-521043-3. OCLC 28378422.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Wong, Jan (1997). Red China Blues. Random House. p. 278.

External links