International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is an international humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide[2] which was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and to prevent and alleviate human suffering.

The Movement logo in the six official languages: English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese and Russian | |

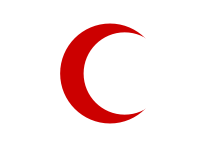

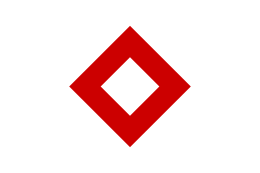

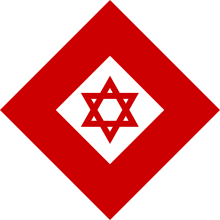

The Geneva Conventions' three emblems in use: Red Cross, Red Crescent, Red Crystal | |

| Founded |

Geneva, Switzerland |

|---|---|

| Founders | Henry Dunant, Gustave Moynier, Théodore Maunoir, Guillaume-Henri Dufour, Louis Appia |

| Type | Non-governmental organization, Non-profit organization |

| Focus | Humanitarianism |

| Location | |

Area served | Worldwide |

| Method | Aid |

Volunteers | Around 17 million[1] |

| Website | www media |

The movement consists of several distinct organizations that are legally independent from each other, but are united within the movement through common basic principles, objectives, symbols, statutes and governing organisations. The movement's parts are:

- The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is a private humanitarian institution founded in 1863 in Geneva, Switzerland, in particular by Henry Dunant and Gustave Moynier. Its 25-member committee has a unique authority under international humanitarian law to protect the life and dignity of the victims of international and internal armed conflicts. The ICRC was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on three occasions (in 1917, 1944 and 1963).[3]

- The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) was founded in 1919 and today it coordinates activities between the 190 National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies within the Movement. On an international level, the Federation leads and organizes, in close cooperation with the National Societies, relief assistance missions responding to large-scale emergencies. The International Federation Secretariat is based in Geneva, Switzerland. In 1963, the Federation (then known as the League of Red Cross Societies) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize jointly with the ICRC.[3]

- National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies exist in nearly every country in the world. Currently 190 National Societies are recognized by the ICRC and admitted as full members of the Federation. Each entity works in its home country according to the principles of international humanitarian law and the statutes of the international Movement. Depending on their specific circumstances and capacities, National Societies can take on additional humanitarian tasks that are not directly defined by international humanitarian law or the mandates of the international Movement. In many countries, they are tightly linked to the respective national health care system by providing emergency medical services.

History

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

Solferino, Jean-Henri Dunant and foundation.

Until the middle of the 19th century, there were no organized and/or well-established army nursing systems for casualties and no safe and protected institutions to accommodate and treat those who were wounded on the battlefield. A devout Reformed Christian, the Swiss businessman Jean-Henri Dunant, in June 1859, traveled to Italy to meet French emperor Napoléon III with the intention of discussing difficulties in conducting business in Algeria, at that time occupied by France.[4] He arrived in the small town of Solferino on the evening of 24 June after the Battle of Solferino, an engagement in the Austro-Sardinian War. In a single day, about 40,000 soldiers on both sides died or were left wounded on the field. Jean-Henri Dunant was shocked by the terrible aftermath of the battle, the suffering of the wounded soldiers, and the near-total lack of medical attendance and basic care. He completely abandoned the original intent of his trip and for several days he devoted himself to helping with the treatment and care for the wounded. He took point in organizing an overwhelming level of relief assistance with the local villagers to aid without discrimination.

Back in his home in Geneva, he decided to write a book entitled A Memory of Solferino which he published using his own money in 1862. He sent copies of the book to leading political and military figures throughout Europe, and people he thought could help him make a change. In addition to penning a vivid description of his experiences in Solferino in 1859, he explicitly advocated the formation of national voluntary relief organizations to help nurse wounded soldiers in the case of war, an idea that was inspired by Christian teaching regarding social responsibility, as well as his experience after the battlefield of Solferino.[5][6][4] In addition, he called for the development of an international treaty to guarantee the protection of medics and field hospitals for soldiers wounded on the battlefield.

In 1863, Gustave Moynier, a Geneva lawyer and president of the Geneva Society for Public Welfare, received a copy of Dunant's book and introduced it for discussion at a meeting of that society. As a result of this initial discussion the society established an investigatory commission to examine the feasibility of Dunant's suggestions and eventually to organize an international conference about their possible implementation. The members of this committee, which has subsequently been referred to as the "Committee of the Five," aside from Dunant and Moynier were physician Louis Appia, who had significant experience working as a field surgeon; Appia's friend and colleague Théodore Maunoir, from the Geneva Hygiene and Health Commission; and Guillaume-Henri Dufour, a Swiss Army general of great renown. Eight days later, the five men decided to rename the committee to the "International Committee for Relief to the Wounded". In October (26–29) 1863, the international conference organized by the committee was held in Geneva to develop possible measures to improve medical services on the battlefield. The conference was attended by 36 individuals: eighteen official delegates from national governments, six delegates from other non-governmental organizations, seven non-official foreign delegates, and the five members of the International Committee. The states and kingdoms represented by official delegates were: Austrian Empire, Grand Duchy of Baden, Kingdom of Bavaria, French Empire, Kingdom of Hanover, Grand Duchy of Hesse, Kingdom of Italy, Kingdom of the Netherlands, Kingdom of Prussia, Russian Empire, Kingdom of Saxony, Kingdom of Spain, United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, and United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.[7]

Among the proposals written in the final resolutions of the conference, adopted on 29 October 1863, were:

- The foundation of national relief societies for wounded soldiers;

- Neutrality and protection for wounded soldiers;

- The utilization of volunteer forces for relief assistance on the battlefield;

- The organization of additional conferences to enact these concepts;

- The introduction of a common distinctive protection symbol for medical personnel in the field, namely a white armlet bearing a red cross.

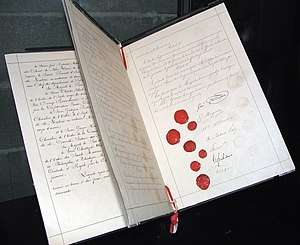

Only one year later, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States of America, the Empire of Brazil, and the Mexican Empire, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field". Representatives of 12 states and kingdoms signed the convention:[8]

The convention contained ten articles, establishing for the first time legally binding rules guaranteeing neutrality and protection for wounded soldiers, field medical personnel, and specific humanitarian institutions in an armed conflict.[9]

Directly following the establishment of the Geneva Convention, the first national societies were founded in Belgium, Denmark, France, Oldenburg, Prussia, Spain, and Württemberg. Also in 1864, Louis Appia and Charles van de Velde, a captain of the Dutch Army, became the first independent and neutral delegates to work under the symbol of the Red Cross in an armed conflict. Three years later in 1867, the first International Conference of National Aid Societies for the Nursing of the War Wounded was convened.

Also in 1867, Jean-Henri Dunant was forced to declare bankruptcy due to business failures in Algeria, partly because he had neglected his business interests during his tireless activities for the International Committee. The controversy surrounding Dunant's business dealings and the resulting negative public opinion, combined with an ongoing conflict with Gustave Moynier, led to Dunant's expulsion from his position as a member and secretary. He was charged with fraudulent bankruptcy and a warrant for his arrest was issued. Thus, he was forced to leave Geneva and never returned to his home city.

In the following years, national societies were founded in nearly every country in Europe. The project resonated well with patriotic sentiments that were on the rise in the late-nineteenth-century, and national societies were often encouraged as signifiers of national moral superiority.[10] In 1876, the committee adopted the name "International Committee of the Red Cross" (ICRC), which is still its official designation today. Five years later, the American Red Cross was founded through the efforts of Clara Barton.[11] More and more countries signed the Geneva Convention and began to respect it in practice during armed conflicts. In a rather short period of time, the Red Cross gained huge momentum as an internationally respected movement, and the national societies became increasingly popular as a venue for volunteer work.

When the first Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in 1901, the Norwegian Nobel Committee opted to give it jointly to Jean-Henri Dunant and Frédéric Passy, a leading international pacifist. More significant than the honor of the prize itself, this prize marked the overdue rehabilitation of Jean-Henri Dunant and represented a tribute to his key role in the formation of the Red Cross. Dunant died nine years later in the small Swiss health resort of Heiden. Only two months earlier his long-standing adversary Gustave Moynier had also died, leaving a mark in the history of the Committee as its longest-serving president ever.

In 1906, the 1864 Geneva Convention was revised for the first time. One year later, the Hague Convention X, adopted at the Second International Peace Conference in The Hague, extended the scope of the Geneva Convention to naval warfare. Shortly before the beginning of the First World War in 1914, 50 years after the foundation of the ICRC and the adoption of the first Geneva Convention, there were already 45 national relief societies throughout the world. The movement had extended itself beyond Europe and North America to Central and South America (Argentine Republic, the United States of Brazil, the Republic of Chile, the Republic of Cuba, the United Mexican States, the Republic of Peru, the Republic of El Salvador, the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, the United States of Venezuela), Asia (the Republic of China, the Empire of Japan and the Kingdom of Siam), and Africa (Union of South Africa).

World War I

With the outbreak of World War I, the ICRC found itself confronted with enormous challenges that it could handle only by working closely with the national Red Cross societies. Red Cross nurses from around the world, including the United States and Japan, came to support the medical services of the armed forces of the European countries involved in the war. On 15 August 1914, immediately after the start of the war, the ICRC set up its International Prisoners-of-War (POW) Agency, which had about 1,200 mostly volunteer staff members by the end of 1914. By the end of the war, the Agency had transferred about 20 million letters and messages, 1.9 million parcels, and about 18 million Swiss francs in monetary donations to POWs of all affected countries. Furthermore, due to the intervention of the Agency, about 200,000 prisoners were exchanged between the warring parties, released from captivity and returned to their home country. The organizational card index of the Agency accumulated about 7 million records from 1914 to 1923. The card index led to the identification of about 2 million POWs and the ability to contact their families. The complete index is on loan today from the ICRC to the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum in Geneva. The right to access the index is still strictly restricted to the ICRC.

During the entire war, the ICRC monitored warring parties' compliance with the Geneva Conventions of the 1907 revision and forwarded complaints about violations to the respective country. When chemical weapons were used in this war for the first time in history, the ICRC vigorously protested against this new type of warfare. Even without having a mandate from the Geneva Conventions, the ICRC tried to ameliorate the suffering of civil populations. In territories that were officially designated as "occupied territories", the ICRC could assist the civilian population on the basis of the Hague Convention's "Laws and Customs of War on Land" of 1907.[12] This convention was also the legal basis for the ICRC's work for prisoners of war. In addition to the work of the International Prisoner-of-War Agency as described above this included inspection visits to POW camps. A total of 524 camps throughout Europe were visited by 41 delegates from the ICRC until the end of the war.

Between 1916 and 1918, the ICRC published a number of postcards with scenes from the POW camps. The pictures showed the prisoners in day-to-day activities such as the distribution of letters from home. The intention of the ICRC was to provide the families of the prisoners with some hope and solace and to alleviate their uncertainties about the fate of their loved ones. After the end of the war, between 1920 and 1922, the ICRC organized the return of about 500,000 prisoners to their home countries. In 1920, the task of repatriation was handed over to the newly founded League of Nations, which appointed the Norwegian diplomat and scientist Fridtjof Nansen as its "High Commissioner for Repatriation of the War Prisoners". His legal mandate was later extended to support and care for war refugees and displaced persons when his office became that of the League of Nations "High Commissioner for Refugees". Nansen, who invented the Nansen passport for stateless refugees and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922, appointed two delegates from the ICRC as his deputies.

A year before the end of the war, the ICRC received the 1917 Nobel Peace Prize for its outstanding wartime work. It was the only Nobel Peace Prize awarded in the period from 1914 to 1918. In 1923, the International Committee of the Red Cross adopted a change in its policy regarding the selection of new members. Until then, only citizens from the city of Geneva could serve in the Committee. This limitation was expanded to include Swiss citizens. As a direct consequence of World War I, a treaty was adopted in 1925 which outlawed the use of suffocating or poisonous gases and biological agents as weapons. Four years later, the original Convention was revised and the second Geneva Convention "relative to the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" was established. The events of World War I and the respective activities of the ICRC significantly increased the reputation and authority of the Committee among the international community and led to an extension of its competencies.

As early as in 1934, a draft proposal for an additional convention for the protection of the civil population in occupied territories during an armed conflict was adopted by the International Red Cross Conference. Unfortunately, most governments had little interest in implementing this convention, and it was thus prevented from entering into force before the beginning of World War II.

World War II

The Red Cross' response to the Holocaust has been the subject of significant controversy and criticism. As early as May 1944, the ICRC was criticized for its indifference to Jewish suffering and death—criticism that intensified after the end of the war, when the full extent of the Holocaust became undeniable. One defense to these allegations is that the Red Cross was trying to preserve its reputation as a neutral and impartial organization by not interfering with what was viewed as a German internal matter. The Red Cross also considered its primary focus to be prisoners of war whose countries had signed the Geneva Convention.[13]

The legal basis of the work of the ICRC during World War II were the Geneva Conventions in their 1929 revision. The activities of the Committee were similar to those during World War I: visiting and monitoring POW camps, organizing relief assistance for civilian populations, and administering the exchange of messages regarding prisoners and missing persons. By the end of the war, 179 delegates had conducted 12,750 visits to POW camps in 41 countries. The Central Information Agency on Prisoners-of-War (Agence centrale des prisonniers de guerre) had a staff of 3,000, the card index tracking prisoners contained 45 million cards, and 120 million messages were exchanged by the Agency. One major obstacle was that the Nazi-controlled German Red Cross refused to cooperate with the Geneva statutes including blatant violations such as the deportation of Jews from Germany and the mass murders conducted in the Nazi concentration camps. Moreover, two other main parties to the conflict, the Soviet Union and Japan, were not party to the 1929 Geneva Conventions and were not legally required to follow the rules of the conventions.

During the war, the ICRC was unable to obtain an agreement with Nazi Germany about the treatment of detainees in concentration camps, and it eventually abandoned applying pressure in order to avoid disrupting its work with POWs. The ICRC was also unable to obtain a response to reliable information about the extermination camps and the mass killing of European Jews, Roma, et al. After November 1943, the ICRC achieved permission to send parcels to concentration camp detainees with known names and locations. Because the notices of receipt for these parcels were often signed by other inmates, the ICRC managed to register the identities of about 105,000 detainees in the concentration camps and delivered about 1.1 million parcels, primarily to the camps Dachau, Buchenwald, Ravensbrück, and Sachsenhausen.

Maurice Rossel was sent to Berlin as a delegate of the International Red Cross; he visited Theresienstadt in 1944. The choice of the inexperienced Rossel for this mission has been interpreted as indicative of his organization's indifference to the "Jewish problem", while his report has been described as "emblematic of the failure of the ICRC" to advocate for Jews during the Holocaust.[15] Rossel's report was noted for its uncritical acceptance of Nazi propaganda.[lower-alpha 1] He erroneously stated that Jews were not deported from Theresienstadt.[16] Claude Lanzmann recorded his experiences in 1979, producing a documentary entitled A Visitor from the Living.[18]

On 12 March 1945, ICRC president Jacob Burckhardt received a message from SS General Ernst Kaltenbrunner allowing ICRC delegates to visit the concentration camps. This agreement was bound by the condition that these delegates would have to stay in the camps until the end of the war. Ten delegates, among them Louis Haefliger (Mauthausen-Gusen), Paul Dunant (Theresienstadt) and Victor Maurer (Dachau), accepted the assignment and visited the camps. Louis Haefliger prevented the forceful eviction or blasting of Mauthausen-Gusen by alerting American troops.

Friedrich Born (1903–1963), an ICRC delegate in Budapest who saved the lives of about 11,000 to 15,000 Jewish people in Hungary. Marcel Junod (1904–1961), a physician from Geneva was one of the first foreigners to visit Hiroshima after the atomic bomb was dropped.

In 1944, the ICRC received its second Nobel Peace Prize. As in World War I, it received the only Peace Prize awarded during the main period of war, 1939 to 1945. At the end of the war, the ICRC worked with national Red Cross societies to organize relief assistance to those countries most severely affected. In 1948, the Committee published a report reviewing its war-era activities from 1 September 1939 to 30 June 1947. The ICRC opened its archives from World War II in 1996.

After World War II

On 12 August 1949, further revisions to the existing two Geneva Conventions were adopted. An additional convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea", now called the second Geneva Convention, was brought under the Geneva Convention umbrella as a successor to the 1907 Hague Convention X. The 1929 Geneva convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" may have been the second Geneva Convention from a historical point of view (because it was actually formulated in Geneva), but after 1949 it came to be called the third Convention because it came later chronologically than the Hague Convention. Reacting to the experience of World War II, the Fourth Geneva Convention, a new Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War", was established. Also, the additional protocols of 8 June 1977 were intended to make the conventions apply to internal conflicts such as civil wars. Today, the four conventions and their added protocols contain more than 600 articles, a remarkable expansion when compared to the mere 10 articles in the first 1864 convention.

.jpg)

In celebration of its centennial in 1963, the ICRC, together with the League of Red Cross Societies, received its third Nobel Peace Prize. Since 1993, non-Swiss individuals have been allowed to serve as Committee delegates abroad, a task which was previously restricted to Swiss citizens. Indeed, since then, the share of staff without Swiss citizenship has increased to about 35%.

On 16 October 1990, the UN General Assembly decided to grant the ICRC observer status for its assembly sessions and sub-committee meetings, the first observer status given to a private organization. The resolution was jointly proposed by 138 member states and introduced by the Italian ambassador, Vieri Traxler, in memory of the organization's origins in the Battle of Solferino. An agreement with the Swiss government signed on 19 March 1993, affirmed the already long-standing policy of full independence of the Committee from any possible interference by Switzerland. The agreement protects the full sanctity of all ICRC property in Switzerland including its headquarters and archive, grants members and staff legal immunity, exempts the ICRC from all taxes and fees, guarantees the protected and duty-free transfer of goods, services, and money, provides the ICRC with secure communication privileges at the same level as foreign embassies, and simplifies Committee travel in and out of Switzerland.

At the end of the Cold War, the ICRC's work actually became more dangerous. In the 1990s, more delegates lost their lives than at any point in its history, especially when working in local and internal armed conflicts. These incidents often demonstrated a lack of respect for the rules of the Geneva Conventions and their protection symbols. Among the slain delegates were:

- Frédéric Maurice. He died on 19 May 1992 at the age of 39, one day after a Red Cross transport he was escorting was attacked in the Bosnian city of Sarajevo.

- Fernanda Calado (Spain), Ingeborg Foss (Norway), Nancy Malloy (Canada), Gunnhild Myklebust (Norway), Sheryl Thayer (New Zealand), and Hans Elkerbout (Netherlands). They were murdered at point-blank range while sleeping in the early hours of 17 December 1996 in the ICRC field hospital in the Chechen city of Nowije Atagi near Grozny. Their murderers have never been caught and there was no apparent motive for the killings.

- Rita Fox (Switzerland), Véronique Saro (Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly known as Zaire), Julio Delgado (Colombia), Unen Ufoirworth (DR Congo), Aduwe Boboli (DR Congo), and Jean Molokabonge (DR Congo). On 26 April 2001, they were en route with two cars on a relief mission in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo when they came under fatal fire from unknown attackers.

- Ricardo Munguia (El Salvador). He was working as a water engineer in Afghanistan and travelling with local colleagues on 27 March 2003 when their car was stopped by unknown armed men. He was killed execution-style at point-blank range while his colleagues were allowed to escape. He was 39 years old. The killing prompted the ICRC to temporarily suspend operations across Afghanistan.[19]

- Vatche Arslanian (Canada). Since 2001, he worked as a logistics coordinator for the ICRC mission in Iraq. He died when he was travelling through Baghdad together with members of the Iraqi Red Crescent. On 8 April 2003 their car accidentally came into the cross fire of fighting in the city.

- Nadisha Yasassri Ranmuthu (Sri Lanka). He was killed by unknown attackers on 22 July 2003 when his car was fired upon near the city of Hilla in the south of Baghdad.

Afghanistan War

ICRC is active in the Afghanistan conflict areas and has set up six physical rehabilitation centers to help land mine victims. Their support extends to the national and international armed forces, civilians and the armed opposition. They regularly visit detainees under the custody of the Afghan government and the international armed forces, but have also occasionally had access since 2009 to people detained by the Taliban.[20] They have provided basic first aid training and aid kits to both the Afghan security forces and Taliban members because, according to an ICRC spokesperson, "ICRC's constitution stipulates that all parties harmed by warfare will be treated as fairly as possible".[21]

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC)

History

In 1919, representatives from the national Red Cross societies of Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and the US came together in Paris to found the "League of Red Cross Societies". The original idea was Henry Davison's, then president of the American Red Cross. This move, led by the American Red Cross, expanded the international activities of the Red Cross movement beyond the strict mission of the ICRC to include relief assistance in response to emergency situations which were not caused by war (such as man-made or natural disasters). The ARC already had great disaster relief mission experience extending back to its foundation.

The formation of the League, as an additional international Red Cross organization alongside the ICRC, was not without controversy for a number of reasons. The ICRC had, to some extent, valid concerns about a possible rivalry between both organizations. The foundation of the League was seen as an attempt to undermine the leadership position of the ICRC within the movement and to gradually transfer most of its tasks and competencies to a multilateral institution. In addition to that, all founding members of the League were national societies from countries of the Entente or from associated partners of the Entente.[22] The original statutes of the League from May 1919 contained further regulations which gave the five founding societies a privileged status and, due to the efforts of Henry P. Davison, the right to permanently exclude the national Red Cross societies from the countries of the Central Powers, namely Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey, and in addition to that the national Red Cross society of Russia. These rules were contrary to the Red Cross principles of universality and equality among all national societies, a situation which furthered the concerns of the ICRC.

The first relief assistance mission organized by the League was an aid mission for the victims of a famine and subsequent typhus epidemic in Poland. Only five years after its foundation, the League had already issued 47 donation appeals for missions in 34 countries, an impressive indication of the need for this type of Red Cross work. The total sum raised by these appeals reached 685 million Swiss francs, which were used to bring emergency supplies to the victims of famines in Russia, Germany, and Albania; earthquakes in Chile, Persia, Japan, Colombia, Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Turkey; and refugee flows in Greece and Turkey. The first large-scale disaster mission of the League came after the 1923 earthquake in Japan which killed about 200,000 people and left countless more wounded and without shelter. Due to the League's coordination, the Red Cross society of Japan received goods from its sister societies reaching a total worth of about $100 million. Another important new field initiated by the League was the creation of youth Red Cross organizations within the national societies.

A joint mission of the ICRC and the League in the Russian Civil War from 1917 to 1922 marked the first time the movement was involved in an internal conflict, although still without an explicit mandate from the Geneva Conventions. The League, with support from more than 25 national societies, organized assistance missions and the distribution of food and other aid goods for civil populations affected by hunger and disease. The ICRC worked with the Russian Red Cross society and later the society of the Soviet Union, constantly emphasizing the ICRC's neutrality. In 1928, the "International Council" was founded to coordinate cooperation between the ICRC and the League, a task which was later taken over by the "Standing Commission". In the same year, a common statute for the movement was adopted for the first time, defining the respective roles of the ICRC and the League within the movement.

During the Abyssinian war between Ethiopia and Italy from 1935 to 1936, the League contributed aid supplies worth about 1.7 million Swiss francs. Because the Italian fascist regime under Benito Mussolini refused any cooperation with the Red Cross, these goods were delivered solely to Ethiopia. During the war, an estimated 29 people lost their lives while being under explicit protection of the Red Cross symbol, most of them due to attacks by the Italian Army. During the civil war in Spain from 1936 to 1939 the League once again joined forces with the ICRC with the support of 41 national societies. In 1939 on the brink of the Second World War, the League relocated its headquarters from Paris to Geneva to take advantage of Swiss neutrality.

In 1952, the 1928 common statute of the movement was revised for the first time. Also, the period of decolonization from 1960 to 1970 was marked by a huge jump in the number of recognized national Red Cross and Red Crescent societies. By the end of the 1960s, there were more than 100 societies around the world. On December 10, 1963, the Federation and the ICRC received the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1983, the League was renamed to the "League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies" to reflect the growing number of national societies operating under the Red Crescent symbol. Three years later, the seven basic principles of the movement as adopted in 1965 were incorporated into its statutes. The name of the League was changed again in 1991 to its current official designation the "International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies". In 1997, the ICRC and the IFRC signed the Seville Agreement which further defined the responsibilities of both organizations within the movement. In 2004, the IFRC began its largest mission to date after the tsunami disaster in South Asia. More than 40 national societies have worked with more than 22,000 volunteers to bring relief to the countless victims left without food and shelter and endangered by the risk of epidemics.

Activities

Organization

Altogether, there are about 97 million people worldwide who serve with the ICRC, the International Federation, and the National Societies, the majority with the latter.

The 1965 International Conference in Vienna adopted seven basic principles which should be shared by all parts of the Movement, and they were added to the official statutes of the Movement in 1986.

Fundamental principles

At the 20th International Conference in Neue Hofburg, Vienna, from 2–9 October 1965, delegates "proclaimed" seven fundamental principles which are shared by all components of the Movement, and they were added to the official statutes of the Movement in 1986. The durability and universal acceptance is a result of the process through which they came into being in the form they have. Rather than an effort to arrive at agreement, it was an attempt to discover what successful operations and organisational units, over the past 100 years, had in common. As a result, the Fundamental Principles of the Red Cross and Red Crescent were not revealed, but found – through a deliberate and participative process of discovery.

That makes it even more important to note that the text that appears under each "heading" is an integral part of the Principle in question and not an interpretation that can vary with time and place.

Humanity

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, born of a desire to bring assistance without discrimination to the wounded on the battlefield, endeavours, in its international and national capacity, to prevent and alleviate human suffering wherever it may be found. Its purpose is to protect life and health and to ensure respect for the human being. It promotes mutual understanding, friendship, cooperation and lasting peace amongst all peoples.

Impartiality

It makes no discrimination as to nationality, race, religious beliefs, class or political opinions. It endeavours to relieve the suffering of individuals, being guided solely by their needs, and to give priority to the most urgent cases of distress.

Neutrality

In order to continue to enjoy the confidence of all, the Movement may not take sides in hostilities or engage at any time in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature.

Independence

The Movement is independent. The National Societies, while auxiliaries in the humanitarian services of their governments and subject to the laws of their respective countries, must always maintain their autonomy so that they may be able at all times to act in accordance with the principles of the Movement.

Voluntary Service

It is a voluntary relief movement not prompted in any manner by desire for gain.

Unity

There can be only one Red Cross or one Red Crescent Society in any one country. It must be open to all. It must carry on its humanitarian work throughout its territory.

Universality

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, in which all Societies have equal status and share equal responsibilities and duties in helping each other, is worldwide.

Activities and organization of the International Conference and the Standing Commission

The International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, which occurs once every four years, is the highest institutional body of the Movement. It gathers delegations from all of the national societies as well as from the ICRC, the IFRC and the signatory states to the Geneva Conventions. In between the conferences, the Standing Commission of the Red Cross and Red Crescent acts as the supreme body and supervises implementation of and compliance with the resolutions of the conference.[23] In addition, the Standing Commission coordinates the cooperation between the ICRC and the IFRC. It consists of two representatives from the ICRC (including its president), two from the IFRC (including its president), and five individuals who are elected by the International Conference. The Standing Commission convenes every six months on average. Moreover, a convention of the Council of Delegates of the Movement takes place every two years in the course of the conferences of the General Assembly of the International Federation. The Council of Delegates plans and coordinates joint activities for the Movement.

Activities and organization

The mission of the ICRC and its responsibilities within the Movement

The official mission of the ICRC as an impartial, neutral, and independent organization is to stand for the protection of the life and dignity of victims of international and internal armed conflicts. According to the 1997 Seville Agreement, it is the "Lead Agency" of the Movement in conflicts. The core tasks of the Committee, which are derived from the Geneva Conventions and its own statutes, are the following:

- to monitor compliance of warring parties with the Geneva Conventions

- to organize nursing and care for those who are wounded on the battlefield

- to supervise the treatment of prisoners of war

- to help with the search for missing persons in an armed conflict (tracing service)

- to organize protection and care for civil populations

- to arbitrate between warring parties in an armed conflict

Legal status and organization

The ICRC is headquartered in the Swiss city of Geneva and has external offices in about 80 countries. It has about 12,000 staff members worldwide, about 800 of them working in its Geneva headquarters, 1,200 expatriates with about half of them serving as delegates managing its international missions and the other half being specialists like doctors, agronomists, engineers or interpreters, and about 10,000 members of individual national societies working on site.

According to Swiss law, the ICRC is defined as a private association. Contrary to popular belief, the ICRC is not a non-governmental organization in the most common sense of the term, nor is it an international organization. As it limits its members (a process called cooptation) to Swiss nationals only, it does not have a policy of open and unrestricted membership for individuals like other legally defined NGOs. The word "international" in its name does not refer to its membership but to the worldwide scope of its activities as defined by the Geneva Conventions. The ICRC has special privileges and legal immunities in many countries, based on national law in these countries or through agreements between the Committee and respective national governments.

According to its statutes it consists of 15 to 25 Swiss-citizen members, which it coopts for a period of four years. There is no limit to the number of terms an individual member can have although a three-quarters majority of all members is required for re-election after the third term.

The leading organs of the ICRC are the Directorate and the Assembly. The Directorate is the executive body of the Committee. It consists of a general director and five directors in the areas of "Operations", "Human Resources", "Resources and Operational Support", "Communication", and "International Law and Cooperation within the Movement". The members of the Directorate are appointed by the Assembly to serve for four years. The Assembly, consisting of all of the members of the Committee, convenes on a regular basis and is responsible for defining aims, guidelines, and strategies and for supervising the financial matters of the Committee. The president of the Assembly is also the president of the Committee as a whole. Furthermore, the Assembly elects a five-member Assembly Council which has the authority to decide on behalf of the full Assembly in some matters. The Council is also responsible for organizing the Assembly meetings and for facilitating communication between the Assembly and the Directorate.

Due to Geneva's location in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, the ICRC usually acts under its French name Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (CICR). The official symbol of the ICRC is the Red Cross on white background with the words "COMITE INTERNATIONAL GENEVE" circling the cross.

Funding and financial matters

The 2009 budget of the ICRC amounts to more than 1 billion Swiss francs. Most of that money comes from the States, including Switzerland in its capacity as the depositary state of the Geneva Conventions, from national Red Cross societies, the signatory states of the Geneva Conventions, and from international organizations like the European Union. All payments to the ICRC are voluntary and are received as donations based on two types of appeals issued by the Committee: an annual Headquarters Appeal to cover its internal costs and Emergency Appeals for its individual missions.

The ICRC is asking donors for more than 1.1 billion Swiss francs to fund its work in 2010. Afghanistan is projected to become the ICRC's biggest humanitarian operation (at 86 million Swiss francs, an 18% increase over the initial 2009 budget), followed by Iraq (85 million francs) and Sudan (76 million francs). The initial 2010 field budget for medical activities of 132 million francs represents an increase of 12 million francs over 2009.

Activities and organization of the International Federation

Mission and responsibilities

The IFRC coordinates cooperation between national Red Cross and Red Crescent societies throughout the world and supports the foundation of new national societies in countries where no official society exists. On the international stage, the IFRC organizes and leads relief assistance missions after emergencies such as natural disasters, manmade disasters, epidemics, mass refugee flights, and other emergencies. As per the 1997 Seville Agreement, the IFRC is the Lead Agency of the Movement in any emergency situation which does not take place as part of an armed conflict. The IFRC cooperates with the national societies of those countries affected – each called the Operating National Society (ONS) – as well as the national societies of other countries willing to offer assistance – called Participating National Societies (PNS). Among the 187 national societies admitted to the General Assembly of the International Federation as full members or observers, about 25–30 regularly work as PNS in other countries. The most active of those are the American Red Cross, the British Red Cross, the German Red Cross, and the Red Cross societies of Sweden and Norway. Another major mission of the IFRC which has gained attention in recent years is its commitment to work towards a codified, worldwide ban on the use of land mines and to bring medical, psychological, and social support for people injured by land mines.

The tasks of the IFRC can therefore be summarized as follows:

- to promote humanitarian principles and values

- to provide relief assistance in emergency situations of large magnitude, such as natural disasters

- to support the national societies with disaster preparedness through the education of voluntary members and the provision of equipment and relief supplies

- to support local health care projects

- to support the national societies with youth-related activities

Legal status and organization

The IFRC has its headquarters in Geneva. It also runs five zone offices (Africa, Americas, Asia Pacific, Europe, Middle East-North Africa), 14 permanent regional offices and has about 350 delegates in more than 60 delegations around the world. The legal basis for the work of the IFRC is its constitution. The executive body of the IFRC is a secretariat, led by a secretary general. The secretariat is supported by five divisions including "Programme Services", "Humanitarian values and humanitarian diplomacy", "National Society and Knowledge Development" and "Governance and Management Services".

The highest decision making body of the IFRC is its General Assembly, which convenes every two years with delegates from all of the national societies. Among other tasks, the General Assembly elects the secretary general. Between the convening of General Assemblies, the Governing Board is the leading body of the IFRC. It has the authority to make decisions for the IFRC in a number of areas. The Governing Board consists of the president and the vice presidents of the IFRC, the chairpersons of the Finance and Youth Commissions, and twenty elected representatives from national societies.

The symbol of the IFRC is the combination of the Red Cross (left) and Red Crescent (right) on a white background surrounded by a red rectangular frame.

Funding and financial matters

The main parts of the budget of the IFRC are funded by contributions from the national societies which are members of the IFRC and through revenues from its investments. The exact amount of contributions from each member society is established by the Finance Commission and approved by the General Assembly. Any additional funding, especially for unforeseen expenses for relief assistance missions, is raised by "appeals"[24] published by the IFRC and comes for voluntary donations by national societies, governments, other organizations, corporations, and individuals.

Internal national societies

Official recognition

National Red Cross and Red Crescent societies exist in nearly every country in the world. Within their home country, they take on the duties and responsibilities of a national relief society as defined by International Humanitarian Law. Within the Movement, the ICRC is responsible for legally recognizing a relief society as an official national Red Cross or Red Crescent society. The exact rules for recognition are defined in the statutes of the Movement. Article 4 of these statutes contains the "Conditions for recognition of National Societies."

- In order to be recognized in terms of Article 5, paragraph 2 b) as a National Society, the Society shall meet the following conditions:

- Be constituted on the territory of an independent State where the Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field is in force.

- Be the only National Red Cross and-or Red Crescent Society of the said State and be directed by a central body which shall alone be competent to represent it in its dealings with other components of the Movement.

- Be duly recognized by the legal government of its country on the basis of the Geneva Conventions and of the national legislation as a voluntary aid society, auxiliary to the public authorities in the humanitarian field.

- Have an autonomous status which allows it to operate in conformity with the Fundamental Principles of the Movement.

- Use the name and emblem of the Red Cross or Red Crescent in conformity with the Geneva Conventions.

- Be so organized as to be able to fulfill the tasks defined in its own statutes, including the preparation in peace time for its statutory tasks in case of armed conflict.

- Extend its activities to the entire territory of the State.

- Recruit its voluntary members and its staff without consideration of race, sex, class, religion or political opinions.

- Adhere to the present Statutes, share in the fellowship which unites the components of the Movement and co-operate with them.

- Respect the Fundamental Principles of the Movement and be guided in its work by the principles of international humanitarian law.

Once a National Society has been recognized by the ICRC as a component of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (the Movement), it is in principle admitted to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies in accordance with the terms defined in the Constitution and Rules of Procedure of the International Federation.

There are today 190 National Societies recognized within the Movement and which are members of the International Federation.

The most recent National Societies to have been recognized within the Movement are the Maldives Red Crescent Society (9 November 2011), the Cyprus Red Cross Society, the South Sudan Red Cross Society (12 November 2013) and, the last, the Tuvalu Red Cross Society (on 1 March 2016).[25]

Activities of national societies on a national and international stage

Despite formal independence regarding its organizational structure and work, each national society is still bound by the laws of its home country. In many countries, national Red Cross and Red Crescent societies enjoy exceptional privileges due to agreements with their governments or specific "Red Cross Laws" granting full independence as required by the International Movement. The duties and responsibilities of a national society as defined by International Humanitarian Law and the statutes of the Movement include humanitarian aid in armed conflicts and emergency crises such as natural disasters through activities such as Restoring Family Links.

Depending on their respective human, technical, financial, and organizational resources, many national societies take on additional humanitarian tasks within their home countries such as blood donation services or acting as civilian Emergency Medical Service (EMS) providers. The ICRC and the International Federation cooperate with the national societies in their international missions, especially with human, material, and financial resources and organizing on-site logistics.

History of the emblems

Emblems in use

The Red Cross

.svg.png)

The Red Cross emblem was officially approved in Geneva in 1863.[26]

The Red Cross flag is not to be confused with the Saint George's Cross depicted on the flag of England, Barcelona, Georgia, Freiburg im Breisgau, and several other places. In order to avoid this confusion the protected symbol is sometimes referred to as the "Greek Red Cross" (now Hellenic Red Cross); that term is also used in United States law to describe the Red Cross. The red cross of the Saint George cross extends to the edge of the flag, whereas the red cross on the Red Cross flag does not.

The Red Cross flag is the colour-switched version of the Flag of Switzerland. In 1906, to put an end to the argument of the Ottoman Empire that the flag took its roots from Christianity, it was decided to promote officially the idea that the Red Cross flag had been formed by reversing the federal colours of Switzerland, although no clear evidence of this origin had ever been found.[27]

The Red Crescent

The Red Crescent emblem was first used by ICRC volunteers during the armed conflict of 1876–8 between the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire. The symbol was officially adopted in 1929, and so far 33 states in the Muslim world have recognized it. In common with the official promotion of the red cross symbol as a colour-reversal of the Swiss flag (rather than a religious symbol), the red crescent is similarly presented as being derived from a colour-reversal of the flag of the Ottoman Empire.

The Red Crystal

On 8 December 2005, in response to growing pressure to accommodate Magen David Adom (MDA), Israel's national emergency medical, disaster, ambulance and blood bank service, as a full member of the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement, a new emblem (officially the Third Protocol Emblem, but more commonly known as the Red Crystal) was adopted by an amendment of the Geneva Conventions known as Protocol III.

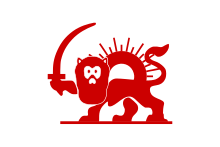

Recognized emblems in disuse

The Red Lion and Sun

The Red Lion and Sun Society of Iran was established in 1922 and admitted to the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement in 1923.[28] However, some report the symbol was introduced at Geneva in 1864[29] as a counter example to the crescent and cross used by two of Iran's rivals, the Ottoman and the Russian empires. Although that claim is inconsistent with the Red Crescent's history, that history also suggests that the Red Lion and Sun, like the Red Crescent, may have been conceived during the 1877–1878 war between Russia and Turkey.

Due to the emblem's association with the Iranian monarchy, the Islamic Republic of Iran replaced the Red Lion and Sun with the Red Crescent in 1980, consistent with two existing Red Cross and Red Crescent symbols. Although the Red Lion and Sun has now fallen into disuse, Iran has in the past reserved the right to take it up again at any time; the Geneva Conventions continue to recognize it as an official emblem, and that status was confirmed by Protocol III in 2005 even as it added the Red Crystal.[30]

Unrecognized emblems

The Red Star of David (Magen David Adom)

For over 50 years, Israel requested the addition of a red Star of David, arguing that since Christian and Muslim emblems were recognized, the corresponding Jewish emblem should be as well. This emblem has been used by Magen David Adom (MDA), or Red Star of David, but it is not recognized by the Geneva Conventions as a protected symbol.[31] The first use of the ″Magen David Adom″ was during the Anglo Boer War in South Africa (1899–1902) when it was used by the Ambulance Corps founded by Ben Zion Aaron in Johannesburg as a first aid corps to assist the Boer forces. Permission was given by President Paul Kruger of the South African Republic for the Star of David to be used as its insignia, rather than the conventional red cross.[32]

The Red Cross and Red Crescent movement repeatedly rejected Israel's request over the years, stating that the Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems were not meant to represent Christianity and Islam but were colour reversals of the Swiss and the Ottoman flags, and also that if Jews (or another group) were to be given another emblem, there would be no end to the number of religious or other groups claiming an emblem for themselves. They reasoned that a proliferation of red symbols would detract from the original intention of the Red Cross emblem, which was to be a single emblem to mark vehicles and buildings protected on humanitarian grounds.

Certain Arab nations, such as Syria, also protested against the entry of MDA into the Red Cross movement, making consensus impossible for a time. However, from 2000 to 2006 the American Red Cross withheld its dues (a total of $42 million) to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) because of IFRC's refusal to admit MDA;[33] this ultimately led to the creation of the Red Crystal emblem and the admission of MDA on June 22, 2006.

The Red Star of David is not recognized as a protected symbol outside Israel; instead the MDA uses the Red Crystal emblem during international operations in order to ensure protection. Depending on the circumstances, it may place the Red Star of David inside the Red Crystal, or use the Red Crystal alone.

1996 hostage crisis allegations

The Australian TV network ABC and the indigenous rights group Rettet die Naturvölker released a documentary called Blood on the Cross in 1999. It alleged the involvement of the Red Cross with the British and Indonesian military in a massacre in the Southern Highlands of Western New Guinea during the World Wildlife Fund's Mapenduma hostage crisis of May 1996, when Western and Indonesian activists were held hostage by separatists.[34][35]

Following the broadcast of the documentary, the Red Cross announced publicly that it would appoint an individual outside the organization to investigate the allegations made in the film and any responsibility on its part. Piotr Obuchowicz was appointed to investigate the matter.[36] The report categorically states that the Red Cross personnel accused of involvement were proven not to have been present; that a white helicopter was probably used in a military operation, but the helicopter was not a Red Cross helicopter, and must have been painted by one of several military organizations operating in the region at the time. Perhaps the Red Cross logo itself was also used, although no hard evidence was found for this; that this was part of the military operation to free the hostages, but was clearly intended to achieve surprise by deceiving the local people into thinking that a Red Cross helicopter was landing; and that the Red Cross should have responded more quickly and thoroughly to investigate the allegations than it did.[37]

See also

- Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement

- First Aid Convention Europe

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC)

- List of National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

- World Red Cross and Red Crescent Day

- Red Swastika Society

Notes

-

- Livia Rothkirchen: "In contrast to those of the Danish delegates, Rossel’s report was phrased in positive terms, falling in line with German propaganda."[16]

- Lucy Dawidowicz: "[Rossel's] acceptance of everything he had seen... and everything he had been told... was total and complacent. The report which he prepared for his superiors in the Red Cross was exactly what the Germans had hoped for... a totally uncritical, even approving affirmation of their propaganda."[17]

References

- Citations

- "IFRC annual report 2015" (PDF).

- "Take a Class". Red Cross. Archived from the original on June 26, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- "Nobel Laureates Facts — Organizations". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- Young, John; Hoyland, Greg (14 July 2016). Christianity: A Complete Introduction. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 354. ISBN 978-1-4736-1577-9.

- Sending, Ole Jacob; Pouliot, Vincent; Neumann, Iver B. (20 August 2015). Diplomacy and the Making of World Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-316-36878-7.

- Stefon, Matt (2011). Christianity: History, Belief, and Practice. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-61530-493-6.

- Bennett, Angela (2006). The Geneva Convention. The Hidden Origins of the Red Cross. Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0752495828.

- "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 22 August 1864". Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross ICRC. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- Telò, Mario (2014). Globalisation, Multilateralism, Europe: Towards a Better Global Governance?. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781409464495.

- Dromi, Shai M. (2016). "For good and country: nationalism and the diffusion of humanitarianism in the late nineteenth century". The Sociological Review. 64 (2): 79–97. doi:10.1002/2059-7932.12003.

- "The Story of My Childhood". World Digital Library. 1907. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- "Understanding the Hague Convention". US Department of State. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Farré & Schubert 2009, p. 72.

- Schur 1997.

- Farré & Schubert 2009, p. abstract.

- Rothkirchen 2006, p. 258.

- Dawidowicz 1975, p. 138.

- "VIVANT QUI PASSE. AUSCHWITZ 1943 – THERESIENSTADT 1944. R: Lanzmann [FR, 1997]". Cine-holocaust.de. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- "Swiss ICRC delegate murdered". www.irinnews.org. IRIN. 28 March 2003. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

Ricardo Munguia, a Swiss citizen of Salvadorian origin was travelling with Afghan colleagues on an assignment to improve the water supply to the district. He was shot in cold blood on Thursday by a group of unidentified assailants who stopped the vehicles transporting them ... the assailants had shot the 39-year-old water and habitat engineer in the head and burned one car, warning two Afghans accompanying him not to work for foreigners ... Asked what action ICRC was taking, Bouvier explained that 'for the time being, the ICRC has decided to temporarily freeze all field trips in Afghanistan, calling all staff to the main delegation's offices.'

- "Afghanistan: first ICRC visit to detainees in Taliban custody". ICRC. 15 December 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "Red Cross in Afghanistan gives Taliban first aid help". BBC News. 26 May 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Dromi, Shai M. (2020). Above the fray: The Red Cross and the making of the humanitarian NGO sector. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0226680101.

- "Role and Mandate of the Standing Commission". Standing Commission of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- "Appeals". IFRC. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "Tuvalu Red Cross Society becomes 190th member of the IFRC". IFRC. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "The history of the emblems". ICRC. 14 January 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- Boissier, Pierre (1985). From Solferino to Tsushima. Henry Durant Institute. p. 77. ISBN 978-2-88044-012-1. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "History of the Iranian Red Crescent Society". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem (Protocol III), 8 December 2005 Article 1 – Respect for and scope of application of this Protocol". ICRC. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "About Us". American Friends of Magen David Adom. Archived from the original on 1 March 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- South African Jewish Year Book. South African Jewish Historical Society. 1929. pp. 105–110.

- "American Red Cross Welcomes Israel's Magen David Adom and Palestine Red Crescent Society to International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement" (Press release). American Red Cross. 21 June 2006. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009.

- "Blood On the Cross". Engagemedia. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- Leith, Denise (2002). The politics of power: Freeport in Suharto's Indonesia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2566-9.

- "ICRC steps up probe into Irian Jaya case". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Barber, Paul, TAPOL, the Indonesia Human Rights Campaign, Irian Jaya: The Record, April 20–30, 2000.

- Print sources

- Dawidowicz, Lucy S. (1975). "Bleaching the Black Lie: The Case of Theresienstadt". Salmagundi (29): 125–140. JSTOR 40546857.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farré, Sébastien; Schubert, Yan (2009). "L'illusion de l'objectif" [The Illusion of the Objective]. Le Mouvement Social (in French). 227 (2): 65–83. doi:10.3917/lms.227.0065.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rothkirchen, Livia (2006). The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia: Facing the Holocaust. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0502-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schur, Herbert (1997). "Review of Karny, Miroslav, ed., Terezinska pametni kniha". Retrieved 16 September 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

Books

- Bennett, Angela. The Geneva Convention: The Hidden Origins of the Red Cross. Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire, England, 2005. ISBN 0-7509-4147-2

- Boissier, Pierre. History of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Volume I: From Solferino to Tsushima. Henry Dunant Institute, Geneva, 1985. ISBN 2-88044-012-2

- Bugnion, François. The International Committee of the Red Cross and the Protection of War Victims. ICRC & Macmillan (ref. 0503), Geneva, 2003. ISBN 0-333-74771-2

- Dunant, Henry. A Memory of Solferino. ICRC, Geneva 1986. ISBN 2-88145-006-7

- Durand, André. History of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Volume II: From Sarajevo to Hiroshima. Henry Dunant Institute, Geneva, 1984. ISBN 2-88044-009-2

- Farmborough, Florence. With the Armies of the Tsar: A Nurse at the Russian Front 1914–1918. Stein and Day, New York, 1975. ISBN 0-8128-1793-1

- Favez, Jean-Claude. The Red Cross and the Holocaust, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Forsythe, David P. Humanitarian Politics: The International Committee of the Red Cross. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1978. ISBN 0-8018-1983-0

- Forsythe, David P. The Humanitarians: The International Committee of the Red Cross. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005. ISBN 0-521-61281-0

- Haug, Hans. Humanity for All: The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Henry Dunant Institute, Geneva in association with Paul Haupt Publishers, Bern, 1993. ISBN 3-258-04719-7

- Handbook of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. 13th edition, International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, 1994. ISBN 2-88145-074-1

- Hutchinson, John F. Champions of Charity: War and the Rise of the Red Cross. Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado, 1997. ISBN 0-8133-3367-9

- Moorehead, Caroline. Dunant's Dream: War, Switzerland and the History of the Red Cross. HarperCollins, London, 1998. ISBN 0-00-255141-1 (Hardcover edition); HarperCollins, London 1999, ISBN 0-00-638883-3 (Paperback edition)

- Willemin, Georges; Heacock, Roger. International Organization and the Evolution of World Society. Volume 2: The International Committee of the Red Cross. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Boston, 1984. ISBN 90-247-3064-3

Journal articles

- Bugnion, François. The emblem of the Red Cross: a brief history. ICRC (ref. 0316), Geneva, 1977.

- Bugnion, François. Towards a comprehensive Solution to the Question of the Emblem. Revised 4th edition. ICRC (ref. 0778), Geneva, 2006.

- Forsythe, David P. "The International Committee of the Red Cross and International Humanitarian Law." In: Humanitäres Völkerrecht – Informationsschriften. The Journal of International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict. 2/2003, German Red Cross and Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict, p. 64–77. ISSN 0937-5414

- Lavoyer, Jean-Philippe; Maresca, Louis. The Role of the ICRC in the Development of International Humanitarian Law. In: International Negotiation. 4(3)/1999. Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 503–527. ISSN 1382-340X

- Walters, William C. (2004). An assessment of the capacity of the Red Cross National Societies to address the psychological and social needs of survivors of disasters and complex emergencies in Central and South America (M.S.W. thesis). Wilfrid Laurier University.

- Wylie, Neville. The Sound of Silence: The History of the International Committee of the Red Cross as Past and Present. In: Diplomacy and Statecraft. 13(4)/2002. Routledge/ Taylor & Francis, pp. 186–204, ISSN 0959-2296

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. |

- The International RCRC Movement – Who we are

- The magazine of the international RCRC Movement

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC)

- Standing Commission of the Red Cross and Red Crescent

- International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent

- International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in the Dodis database of the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland