Yemenite War of 1979

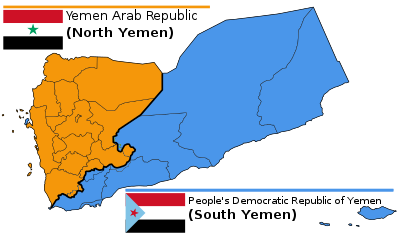

The Yemenite War of 1979 was a short military conflict between the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR; North Yemen) and the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY; South Yemen).[1] The war developed out of a breakdown in relations between the two countries after the president of North Yemen, Ahmad al-Ghashmi, was killed on 24 June 1978 and Salim Rubai Ali, a moderate Marxist who had been working on a proposed merger between the two Yemens, was murdered two days later.[2] The hostility of the rhetoric from the new leadership of both countries escalated, leading to small scale border fighting, which then in turn escalated into a full blown war in February 1979. North Yemen appeared on the edge of a decisive defeat after a three-front invasion by South Yemeni combined arms formation,[3] however this was prevented by a successful mediation in the form of the Kuwait Agreement of 1979, which resulted in Arab League forces being deployed to patrol the North-South border. An agreement to unite both countries was also signed, although was not implemented.[4]

Conflict

The Marxist government of South Yemen was alleged to be supplying aid to rebels in the north through the National Democratic Front and crossing the border.[5]

On 24 February, forces from North and South Yemen began firing at each other across the border.[4] Force from North Yemen, led by some radical army officers, crossed the border into South Yemen and attacked a number of villages.[4] The PDRY, with support from the Soviet Union, Cuba, and East Germany, responded by invading the north using 3 regular divisions and a Tactical Air Force regiment.[4] The PDRY was also supported by the NDF,[6] who were in the midst of fighting their own rebellion against the government of North Yemen. Within 3 days of the invasion, the numerically smaller South Yemeni forces had established complete air superiority over the theater, thus forcing the North Yemeni Ground Forces on the back foot for the rest of the War.

The South Yemeni attack carried the advantage of surprise and was spearheaded by the an Artillery barrage and groups of Sappers, who were effectively able to blow up the early warning air defences and radars and thus help the Air Force establish air superiority within days over much of Taizz and Dhale Governorates and parts of Al Bayda Governorate, after getting the better off the weak resistance put up by a North Yemeni Air Force squadron in a dogfight that saw most of the North Yemeni planes being downed. After the initial Air Force attack, a South Yemeni Armoured Division composed of T-55 and T-62 Tanks spearheaded the ground assault on a Yemeni Armoured Division stationed near Taizz city, followed by an Infantry Division covered by an Artillery Brigade providing fire support with BM-21 Grad rockets and M-46 field howitzers. This was soon followed by the South Yemeni Air Force further destroying several North Yemeni MiG-21 fighter jets and helicopters on the ground in airfields and airbases in Dhamar, thus preventing any chance of a Northern aerial counter-attack. The war dragged on for nearly a month, with North Yemen being unable to send reinforcement units from Sana'a down to Taizz due to the constant Southern airstrikes and aggressive air patrolling hitting reinforcement convoys on difficult and winding mountain roads as far north as Dhamar. Although Northern forces vastly outnumbered Southern forces overall, they were outnumbered and overwhelmed within the theater of operations in and around Taizz and Dhale, since a single Division had to face an attack from three enemy Divisions without any reinforcement or close air support due to the Southern air patrolling and airstrikes on Northern roads throughout the month. On 8 March, the South Yemeni Air Force managed to carry out an attack on Sana'a City, with 3 Su-22 bombers with 5 MiG-21 fighters flying top cover, dropping 500-pound bombs on a Mechanized Infantry base and strafing the Judges' Court and Central Prison, causing mass panic among civilians. North Yemeni Air Defences operating the SA-3 engaged and managed to shoot down one of the bombers and one MiG-21, capturing the pilots. Another deep raid on 10th March saw 4 South Yemeni MiG-21s strafe an Airbase and the Sea port near Hodeidah, sinking a civilian Egyptian cargo ship, but being met with sudden interception from a squadron of North Yemeni MiG-21s with the result that one of the South Yemeni MiGs were shot down and crashed into the Sea, killing the Pilot. With losses escalating, Northern forces appearing on the verge of exhaustion, and Southern forces capturing a wide range of Northern territory and besieging the cities of Taizz and Al Bayda within two weeks, and a South Yemeni Infantry Brigade maanging to capture some suburbs of Taizz, Saudi Arabia and the United States rushed arms to bolster the government of North Yemen by 9-10 March. Citing the alleged Soviet-backed PDRY aggression against the YAR, and the threat this could pose to U.S. ally Saudi Arabia, the United States greatly stepped up military assistance to the YAR government.[6]

As part of this the U.S. shipped 18 F-5E planes to the YAR in order to strengthen the government. However, there were no YAR pilots trained in flying the F-5E, and as a result the U.S. and Saudi Arabia arranged to have 80 Taiwanese pilots plus ground crew and Iraqi anti-air defense units sent to North Yemen.[7] A U.S. Navy task force was also sent to the Arabian Sea in response to the escalating violence.[4] The War showed the weakness and lacunae in the North Yemeni Military training and equipment, and soon its allies started an aggressive re-armament and training programme for the YAR Army to enable it to regain strategic balance and parity against superior trained PDRY forces. The North Yemen allies, led by Egypt, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, soon provided much military aid, equipment and training in order to plug the shortage caused due to the losses in the War, and by 1983-84, the North had regained its strength [8][9]

Aftermath

Kuwait Agreement of 1979

On 20 March the leaders of North and South Yemen called a bilateral ceasefire met in Kuwait for a reconciliation summit, in part at the strong insistence of Iraq.[3] The talks were mediated by the Arab League. Under the Kuwait Agreement, both parties reaffirmed their commitment to the goal and process of Yemeni Unification, as had been spelled out in the Cairo Agreement of 1972. This agreement to unify was particularly the result of pressure from Iraq, Syria, and Kuwait, all of whom advocated for a unified Arab world in order to best respond to the issues arising from the Camp David accords, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the Iranian Revolution. POWs were exchanged within the next two months, and work for a draft constitution for a united Yemen proceeded over the next two years, however most attempts to implement the spirit and letter of the agreement were put on hold until 1982, and the end of the rebellion by the South Yemen supported National Democratic Front.[10]

References

- Burrowes, Robert, Middle East dilemma: the politics and economics of Arab integration, Columbia University Press, 1999, pages 187 to 210

- Kohn, George (2013). Dictionary of Wars. Routledge. ISBN 1135955018.

- Burrowes, Robert D. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Yemen. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 190.

- Kohn, George C. (2006). "Dictionary of Wars". Infobase Publishing. p. 615.

- Hermann, Richard, Perceptions and behavior in Soviet foreign policy, University of Pittsburgh Pre, 1985, page 152

- Burrowes, Robert D. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Yemen. Rowman & Littlefield. p. XXXII Chronology.

- "'Never' a wake-up call". Taipei Times. 15 May 2010.

- Hoagland, Edward, Balancing Acts,Globe Pequot, 1999, page 218

- Interview with Al-Hamdani Middle East Research and Information Reports, February 1985

- Burrowes, Robert D. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Yemen. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 219.