Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan (English: /miːkoʊˈjɑːn/; Russian: Анаста́с Ива́нович Микоя́н; Armenian: Անաստաս Հովհաննեսի Միկոյան; 25 November 1895 – 21 October 1978) was an Armenian Communist revolutionary, Old Bolshevik and Soviet statesman during the mandates of Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev. He was the only Soviet politician who managed to remain at the highest levels of power within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, as that power oscillated between the Central Committee and the Politburo, from the latter days of Lenin's rule, throughout the eras of Stalin and Khrushchev, until his peaceful retirement after the first months of Brezhnev's rule.

Anastas Mikoyan Анаста́с Микоя́н Անաստաս Միկոյան | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 15 July 1964 – 9 December 1965 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Leonid Brezhnev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Podgorny | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 28 February 1955 – 15 July 1964 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Nikolai Bulganin Nikita Khrushchev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Nikolai Bulganin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Pervukhin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan 25 November 1895 Sanahin, Yelizavetpol Governorate, Russian Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 21 October 1978 (aged 82) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Citizenship | Soviet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Armenian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | RSDLP (Bolsheviks) (1915-1918) Russian Communist Party (1918-1966) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Ashkhen Mikoyan (née Tumanyan) (1896–1962) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Sergo, Stepan, Vano, Aleksei, Vladimir1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Civil servant, statesman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 Vladimir was killed in the fighting during the Battle of Stalingrad. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mikoyan became an early convert to the Bolshevik cause. He was a strong supporter of Stalin during the immediate post-Lenin years. During Stalin's rule, Mikoyan held several high governmental posts, including that of Minister of Foreign Trade. By the end of Stalin's rule, Mikoyan began to lose favour with him, and in 1949, Mikoyan lost his long-standing post of minister of foreign trade. In October 1952 at the 19th Party Congress Stalin even attacked Mikoyan viciously. When Stalin died in 1953, Mikoyan again took a leading role in policy-making. He backed Khrushchev and his de-Stalinization policy and became First Deputy Premier under Khrushchev. Mikoyan's position under Khrushchev made him the second most powerful figure in the Soviet Union at the time.

Mikoyan made several key trips to communist Cuba and to the United States, acquiring an important stature on the international diplomatic scene, especially with his skill in exercising soft power to further Soviet interests. In 1964 Khrushchev was forced to step down in a coup that brought Brezhnev to power. Mikoyan served as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, the nominal Head of State, from 1964 until his forced retirement in 1965.

Early life and career

Mikoyan was born to Armenian parents in the village of Sanahin, then part of the Yelizavetpol Governorate of the Russian Empire (currently part of Alaverdi in Armenia's Lori Province) in 1895. His father, Hovhannes, was a carpenter and his mother, a rug weaver. He had one younger brother, Artem Mikoyan, who would be the co-founder of the MiG aviation design bureau, which became one of the primary design bureaus of fast jets in Soviet military aviation.[1]

Mikoyan received his education at the Nersisian School in Tiflis and the Gevorgian Seminary in Vagharshapat (Echmiadzin), both affiliated with the Armenian Apostolic Church.[2] Religion, however, played an increasingly insignificant role in his life. He would later remark that his continued studies in theology drew him closer to atheism: "I had a very clear feeling that I didn't believe in God and that I had in fact received a certificate in materialist uncertainty; the more I studied religious subjects, the less I believed in God." Before becoming active in politics Mikoyan had already dabbled in the study of liberalism and socialism.[3]

At the age of twenty, he formed a workers' soviet in Echmiadzin. In 1915 Mikoyan formally joined the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (later known as the Bolshevik Party) and became a leader of the revolutionary movement in the Caucasus.[2] His interactions with Soviet revolutionaries led him to Baku, where he became the co-editor for the Armenian-language newspaper Sotsyal-Demokrat and later for the Russian-language paper Izvestia Bakinskogo Soveta.[2] During this time, he is said to have robbed a bank in Tiflis with TNT and had his nose broken in street fighting.[4]

Russian Revolution

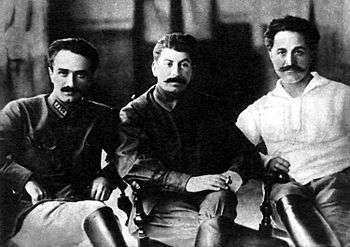

After the February 1917 revolution that toppled the Tsarist government, Mikoyan and other Bolsheviks fought against anti-Bolshevik elements in the Caucasus.[2] Mikoyan became a commissar in the newly formed Red Army and continued to fight in Baku against anti-Bolshevik forces. He was wounded in the fighting and was noted for saving the life of fellow Party-member Sergo Ordzhonikidze.[5] Afterwards, he continued his Party work, becoming one of the co-founders of the Baku Soviet, which lasted until 1918, when he and twenty-six other commissars fled Baku and were captured by the Transcaspian Government. Known as the Baku 26, all the commissars were executed with the sole exception of Mikoyan; the circumstances of his survival are shrouded in mystery.[6] In February 1919 Mikoyan returned to Baku and resumed his activities there, helping to establish the Baku Bureau of the Caucasus Regional Committee (Kraikom).[7][8]

Politburo member

Mikoyan supported Stalin, whom he had first met in 1919, in the power struggle that followed Lenin's death in 1924;[9] he had become a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee in 1923. As People's Commissar for External and Internal Trade from 1926, he imported ideas from the West, such as the manufacture of canned goods.[2] In 1935 he was elected to the Politburo and was one of the first Soviet leaders to pay goodwill trips to the United States in order to boost economic cooperation. Mikoyan spent three months in the United States, where he not only learned more about its food industry but also met and spoke with Henry Ford and inspected Macy's in New York. When he returned, Mikoyan introduced a number of popular American consumer products to the Soviet Union, including American hamburgers, ice cream, corn flakes, popcorn, tomato juice, grapefruit and corn on the cob.[10]

Mikoyan spearheaded a project to produce a home cookbook, which would encourage a return to the domestic kitchen. The result, The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food (Книга о вкусной и здоровой пище, Kniga o vkusnoi i zdorovoi pishche), was published in 1939, and the 1952 edition sold 2.5 million copies.[11] Mikoyan helped initiate the production of ice cream in the USSR and kept the quality of ice cream under his own personal control until he was dismissed. Stalin made a joke about this, stating, "You, Anastas, care more about ice cream, than about communism."[12] Mikoyan also contributed to the development of meat production in the USSR (particularly, the so-called Mikoyan cutlet), and one of the Soviet-era sausage factories was named after him.[13]

In the late 1930s Stalin embarked upon the Great Purge, a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated against members of the Communist Party, as well as the peasantry and unaffiliated persons. In assessing Mikoyan's role in the purges, historian Simon Sebag-Montefiore states that he "enjoyed the reputation of one of the more decent leaders: he certainly helped the victims later and worked hard to undo Stalin's rule after the Leader's death." Mikoyan tried to save some close-knit companions from being executed. However, in 1936 he enthusiastically supported the execution of Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, claiming it to be a "just verdict." As with other leading officials in 1937, Mikoyan signed death-lists given to him by the NKVD.[14] The purges were often accomplished by officials close to Stalin, giving them the assignment largely as a way to test their loyalty to the regime.

In September 1937 Stalin dispatched Mikoyan, along with Georgy Malenkov and Lavrentiy Beria, with a list of 300 names to Yerevan, the capital of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR), to oversee the liquidation of the Communist Party of Armenia (CPA), which was largely made up of Old Bolsheviks. Mikoyan tried, but failed, to save one from being executed during his trip to Armenia. That person was arrested during one of his speeches to the CPA by Beria. Over a thousand people were arrested and seven of nine members of the Armenian Politburo were sacked from office.[15] In several instances, he intervened on behalf of his colleagues; this leniency towards the persecuted may have been one reason why he was selected by Stalin to oversee the purges in the ASSR.[14]

World War II and de-Stalinization

In September 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union each carved out their own spheres of influence in Poland and Eastern Europe via the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The Soviets arrested 26,000 Polish officers in the eastern portion of Poland and in March 1940, after some deliberation, Stalin and five other members of the Politburo, Mikoyan included, signed an order for their execution as "nationalists and counterrevolutionaries".[16] When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Mikoyan was placed in charge of organizing the transportation of food and supplies. His son Vladimir, a pilot in the Red Air Force, died in combat when his plane was shot down over Stalingrad.[17] Mikoyan's main assignment throughout the war was supplying the Red Army with materials, food and other necessities.[18]

Mikoyan is also credited for his large role in the 1941 relocation of Soviet industry from the threatened western cities such as Moscow and Leningrad, eastward to the Urals, Western Siberia, the Volga region, and other safer zones.[19]

Mikoyan became a Special Representative of the State Defense Committee in 1941 by Stalin's orders; he was until that point not a member because Beria believed he would be of better use in government administration.[20] Mikoyan was decorated with a Hero of Socialist Labor in 1943 for his efforts. In 1946 he became the Vice-Premier of the Council of Ministers.[21]

Shortly before his death in 1953, Stalin considered launching a new purge against Mikoyan, Vyacheslav Molotov, and several other Party leaders. Mikoyan and others gradually began to fall out of favor and, in one instance, were accused of plotting against Stalin.[22] Stalin's plans never came to fruition, however, as he died before he could put them into motion.[5] Mikoyan originally argued in favor of keeping Stalin's right-hand man Beria from punishment but later gave in to popular support among Party members for his arrest. Mikoyan remained in the government after Stalin's death, in the post of Minister of Trade, under Malenkov.[23] He supported Nikita Khrushchev in the power struggle to succeed Stalin, and became First Deputy Premier in recognition of his services.[24]

In 1956 Mikoyan helped Khrushchev organize the Secret Speech, which Khrushchev delivered to the 20th Party Congress, that denounced Stalin's personality cult.[25] It was he, and not Khrushchev, who made the first anti-Stalinist speech at the 20th Congress.[26] Along with Khrushchev, he helped roll back some of the stifling restrictions on nationalism and culture imposed during Stalin's time. In 1954, he visited his native Armenia and gave a speech in Yerevan, where he encouraged Armenians to republish the works of Raffi and the purged writer Yeghishe Charents.[27]

In 1957 Mikoyan refused to back an attempt by Malenkov and Molotov to remove Khrushchev from power; he thus secured his position as one of Khrushchev's closest allies. He backed Khrushchev because of his strong support for de-Stalinization and his belief that a triumph by the plotters might have given way to purges similar to the ones in the 1930s.[28] In recognition of his support and his economic talents, Khrushchev appointed Mikoyan First Deputy Premier and liked to playfully describe him as "My rug merchant."

Foreign diplomacy

China

Mikoyan was the first Politburo member to make direct contact with the Chinese communist party chairman, Mao Zedong. He arrived at Mao's headquarters on 30 January 1949, one day before the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek was forced to abandon Nanjing, which was then China's capital, and move to Canton. Mikoyan reported that Mao was proclaiming Stalin to be the supreme leader of world communism and 'teacher of the Chinese people', but in his report he added that Mao did not genuinely believe what he was saying.[29] It was at Mikoyan's insistence that the Chinese communists arrested the US journalist Sidney Rittenberg.[30]

Czechoslovakia

On 11 November 1951, Mikoyan made a sudden visit to Prague to deliver a message from Stalin to President Klement Gottwald insisting that the Rudolf Slansky, former Secretary-General of the Czechoslovak communist party, should be arrested. When Gottwald demurred, Mikoyan broke off the interview to ring Stalin, before repeating the demand, after which Gottwald capitulated. This was the biggest single step towards the preparation of the Slansky Trial.[31] Mikoyan's role in the repression in Czechoslovakia was kept secret until the Prague Spring of 1968.

Hungary

In October 1956 Mikoyan was sent to the People's Republic of Hungary to gather information on the developing crisis caused by the revolution against the communist government there. Together with Mikhail Suslov, Mikoyan traveled to Budapest in an armored personnel carrier, in view of the shooting in the streets. He sent a telegram to Moscow reporting his impressions of the situation. "We had the impression that Ernő Gerő especially, but the other comrades as well, are exaggerating the strength of the opponent and underestimating their own strength," he and Suslov wrote.[32] Mikoyan strongly opposed the decision by Khrushchev and the Politburo to use Soviet troops, believing it would destroy the Soviet Union's international reputation, instead arguing for the application of "military intimidation" and economic pressure.[33] The crushing of the revolution by Soviet forces nearly led to Mikoyan's resignation.[34]

United States

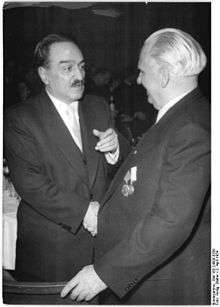

Khrushchev's liberalization of hard-line policies led to an improvement in relations between the Soviet Union and the United States during the late 1950s. As Khrushchev's primary emissary, Mikoyan visited the United States several times. Despite the volatility of the Cold War between the two superpowers, many Americans received Mikoyan amiably, including Minnesota Democrat Hubert Humphrey, who characterized him as someone who showed a "flexibility of attitude" and New York governor Averell Harriman, who described him as a "less rigid" Soviet politician.[35]

During November 1958 Khrushchev made an unsuccessful attempt to turn all of Berlin into an independent, demilitarized "free city", giving the United States, Great Britain, and France a six-month ultimatum to withdraw their troops from the sectors they still occupied in West Berlin, or he would transfer control of Western access rights to the East Germans. Mikoyan disapproved of Khrushchev's actions, claiming they violated "Party principle." Khrushchev had proposed the ultimatum to the West before discussing it with the Central Committee. Ruud van Djik, a historian, believed Mikoyan was angry because Khrushchev didn't consult him about the proposal. When asked by Khrushchev to ease tension with the United States, Mikoyan responded, "You started it, so you go!"[36]

However, Mikoyan eventually left for Washington, which was the first time a senior governing member of the USSR's Council of Ministers visited the United States on a diplomatic mission to its leadership. Furthermore, Mikoyan approached the mission with an unprecedented informality, beginning with phrasing his visa request to US Embassy as "a fortnight's holiday" to visit his friend, Mikhail Menshikov, the then Soviet Ambassador to the United States. While the White House was taken off guard by this seemingly impromptu diplomatic mission, Mikoyan was invited to speak to numerous elite American organizations such as the Council on Foreign Relations and the Detroit Club in which he professed his hopes for the USSR to have a more peaceful relationship with the US. In addition to such well received engagements, Mikoyan indulged in more informal opportunities to meet the public such as having breakfast at a Howard Johnson's restaurant on the New Jersey Turnpike, visiting Macy's Department Store in New York City and meeting celebrities in Hollywood like Jerry Lewis and Sophia Loren before having an audience with President Dwight Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles.[37] Although Mikoyan failed to alter the US's Berlin policy,[38] he was hailed in the US for easing international tensions with an innovative emphasis on soft diplomacy that largely went over well with the American public.[39]

Mikoyan disapproved of Khrushchev's walkout from the 1960 Paris Summit over the U-2 Crisis of 1960, which he believed kept tension in the Cold War high for another fifteen years. However, throughout this time, he remained Khrushchev's closest ally in the upper echelons of the Soviet leadership. As Mikoyan later noted, Khrushchev "engaged [in] inexcusable hysterics".[40]

In November 1963 Mikoyan was asked by Khrushchev to represent the USSR at President John F. Kennedy's funeral.[41] At the funeral ceremony, Mikoyan appeared visibly shaken by the president's death and was approached by Jacqueline Kennedy, who took his hand and conveyed to him the following message: "Please tell Mr. Chairman [Khrushchev] that I know he and my husband worked together for a peaceful world, and now he and you must carry on my husband's work."[42]

Cuba and the Missile Crisis

The Soviet government welcomed the overthrow of Cuban President Fulgencio Batista by Fidel Castro's pro-socialist rebels in 1959. Khrushchev realized the potential of a Soviet ally in the Caribbean and dispatched Mikoyan as one of the top diplomats in Latin America. He was the first Soviet official (discounting Soviet intelligence officers) to visit Cuba after the revolution, and secured important trade agreements with the new government.[38] He left Cuba with a very positive impression, saying that the atmosphere there made him feel "as though I had returned to my childhood."[43]

Khrushchev told Mikoyan of his idea of shipping Soviet missiles to Cuba. Mikoyan was opposed to the idea, and was even more opposed to giving the Cubans control over the Soviet missiles.[38] In early November 1962, after the United States and the Soviet Union agreed to a framework to remove Soviet nuclear missiles from Cuba, Khrushchev dispatched Mikoyan to Havana to help persuade Castro to cooperate in the withdrawal.[44][45] Just prior to beginning negotiations with Castro, Mikoyan was informed about the death of his wife, Ashkhen, in Moscow; rather than return there for the funeral, Mikoyan opted to stay and sent his son Sergo there instead.[46]

Castro was adamant that the missiles remain but Mikoyan, seeking to avoid a full-fledged confrontation with the United States, attempted to convince him otherwise. He told Castro, "You know that not only in these letters but today also, we hold to the position that you will keep all the weapons and all the military specialists with the exception of the 'offensive' weapons and associated service personnel, which were promised to be withdrawn in Khrushchev's letter [of October 27]."[47] Castro balked at the idea of further concessions, namely the removal of the Il-28 bombers and tactical nuclear weapons still left in Cuba. But after several tense and grueling weeks of negotiations, he finally relented and the missiles and the bombers were removed in December of that year.[48]

Head of state and coup involvement

On 15 July 1964, Mikoyan was appointed as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, replacing Leonid Brezhnev, who received a promotion within the Party. Mikoyan's new position was largely ceremonial; it was noted that his declining health and old age were being considered.[49]

Some historians are convinced that by 1964 Mikoyan believed that Khrushchev had turned into a liability to the Party, and that he was involved in the October 1964 coup that brought Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin to power.[50] However, William Taubman disputes this, as Mikoyan was the only member of the Presidium (the name for the Politburo at this time) to defend Khrushchev. Mikoyan, however, did vote to force Khrushchev's retirement (so as, in traditional Soviet style, to make the vote unanimous). Alone among Khrushchev's colleagues, Mikoyan wished the former leader well in his retirement, and he, alone, visited Khrushchev at his dacha a few years later. Mikoyan laid a wreath and sent a letter of condolence at Khrushchev's funeral in 1971.[51]

Due to his partial defense of Khrushchev during his ouster, Mikoyan lost his high standing with the new Soviet leadership. The Politburo forced Mikoyan to retire from his seat in the Politburo due to old age. Mikoyan quickly also lost his post as head of state and was succeeded in this post by Nikolai Podgorny on 9 December 1965.[52] Upon his retirement, Mikoyan was awarded the Order of Lenin.[53]

Death, personality, and legacy

As with Khrushchev and other companions, Mikoyan in his last days wrote a frank but selective memoirs from his political career during Stalin's rule.[54] Mikoyan died on 21 October 1978, at the age of 82, from natural causes and was buried at Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. He received six commendations of the Order of Lenin.[2] Mikoyan, in a description by Simon Sebag-Montefiore, was "slim, circumspect, wily and industrious". He has been described as an intelligent man, understanding English, having learned German on his own by translating the German version of Karl Marx's Das Kapital into Russian. Unlike many others, Mikoyan was not afraid to get into a heated argument with Stalin. "One was never bored with Mikoyan", Artyom Sergeev notes, while Khrushchev called him a true cavalier. However, Khrushchev warned of trusting "that shrewd fox from the east."[55] In a close conversation with Vyacheslav Molotov and Nikolai Bukharin, Stalin referred to Mikoyan as a "duckling in politics"; he noted, however, that if Mikoyan ever took a serious shot he would improve.[56] Mikoyan had so many children, five boys and the two sons of the late Bolshevik leader Stepan Shahumyan, that he and his wife faced economic problems. His wife Ashkhen would borrow money from Politburo wives who had fewer children. If Mikoyan had discovered this he would, according to his children, have become furious.[57]

Mikoyan was defiantly proud of his Armenian identity, pointing out: "I am not a Russian. Stalin is not a Russian." He and Stalin were said to share a toast: "To hell with all these Russians!"[4] However, in post-Soviet Armenia he is a divisive and controversial figure like some other Soviet-era Armenian officials.[58] His critics argue that he, as a loyal servant to Stalin, is responsible for the deaths of thousands during the 1930s purges when many Armenian intellectuals were assassinated.[59] According to academician Hayk Demoyan, he "symbolizes evil, mass murders, and an atmosphere of fear."[60] His supporters argue that he was a major figure on global political stage and usually point to his role in the Cuban missile crisis.[59]

Dubbed the Vicar of Bray of politics and known as the "Survivor" during his time, Mikoyan was one of the few Old Bolsheviks who was spared from Stalin's purges and was able to retire comfortably from political life. This was highlighted in a number of popular sayings in Russian, including "From Ilyich [Lenin] to Ilyich [Brezhnev] ... without heart attack or stroke!"(Ot Ilyicha do Ilyicha bez infarkta i paralicha).[55] One veteran Soviet official described his political career in the following manner: "The rascal was able to walk through Red Square on a rainy day without an umbrella [and] without getting wet. He could dodge the raindrops."[55]

Portrayals

Paul Whitehouse played Mikoyan in the 2017 satirical film The Death of Stalin.[61]

Decorations and awards

Notes

- Mikoyan, Stepan Anastasovich (1999). Stepan Anastasovich Mikoyan: An Autobiography. Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing. p. 522. ISBN 978-1-85310-916-4. LCCN 99488415. OCLC 41594812.

- Միկոյան, Անաստաս Հովհաննեսի [Mikoyan, Anastas Hovhannesi] (in Armenian). vii. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences. 1981. p. 542.

- Staff writer (16 September 1957). "Russia: The Survivor". Time: 2. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Staff writer (23 December 1958). "Mikoyan: Soviet Union's Shrewd Trader". Milwaukee Sentinel. p. 7. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Staff writer (16 September 1957). "Russia: The Survivor". Time: 4. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 214.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918–1919. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 401. ISBN 978-0-520-01984-3. LCCN 72129613. OCLC 797273730.

- Mikoyan's activities in Baku are treated in passim in Ronald Grigor Suny, The Baku Commune, 1917-1918: Class and Nationality in the Russian Revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972.

- For more on Mikoyan's and Stalin's first encounter see Stephen Kotkin, Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928. New York: Penguin Press, 2014, p. 465.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 192–193n.

- Russell, Polly; The history cook; The Financial Times (FT Weekend Magazine), 17/18 August 2013, p36.

- (in Russian) Bogdanov, Igor A. Лекарство от скуки, или, История мороженого. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2007, p. 100.

- (in Russian) "Цены на ассортимент ТД Агроторг."

- Montefiore 2005, p. 256.

- Tucker, Robert C. (1992). Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928–1941. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 488–489. ISBN 978-0-393-30869-3. LCCN 89078047. OCLC 26298147.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 333.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 463.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 373.

- Keegan, John (2005). The Second World War. New York: Penguin Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-14-303573-2. LCCN 2005274899. OCLC 60327493.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 383.

- Vasilyevich, Ufarkinym Nikolai. Анастас Иванович, Микоян [Mikoyan, Anastas Ivanovich] (in Russian). warheroes.ru. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Service, Robert, Stalin: A Biography. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press, 2005, pp. 533, 577-80.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 662.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 666.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 652.

- Staff writer (16 September 1957). "Russia: The Survivor (page 5)". Time. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Matossian, Mary Kilbourne. The Impact of Soviet Policies in Armenia. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1962, p. 201.

- Laqueur, Walter (1990) [1965]. Russia and Germany: A Century of Conflict. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-88738-349-6. LCCN 89020685. OCLC 20932380.

- Chang, Jung; Halliday, Jon (2007) [2005]. Mao, the Unknown Story. London: Vintage Books. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-0-09-950737-6. OCLC 774136780.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chang & Halliday 2007, p. 418.

- Komunistická Strana C̆eskoslovenska. Komise pro Vyr̆izování Stranických Rehabilitací. (1971). Pelikán, Jiří (ed.). The Czechoslovak Political Trials, 1950-1954: The Suppressed Report of the Dubcek Government's Commission of Inquiry, 1968. London: MacDonald & Co. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-356-03585-7. LCCN 72877920. OCLC 29358222.

- Mikoyan, Anastas; Suslov, Mikhail (24 October – 4 November 1956). Soviet Documents on the Hungarian Revolution, 24 October – 4 November 1956. Cold War International History Project Bulletin. Government of the Soviet Union. pp. 22–23 and 29–34. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Note: See the Mikoyan-Suslov Report of 24 October in Johanna Granville.

- Gati, Charles (2003). "Foreword". In Békés, Csaba; Byrne, Malcolm; Ranier, János M. (eds.). The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: A History in Documents. Budapest: Central European University Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-963-9241-66-4. OCLC 847476436.

- Taubman 2004, p. 312.

- Staff writer (26 January 1959). "Foreign Relations: Down to Hard Cases". Time. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Taubman 2004, p. 409.

- Kaplan, Fred (2009). 1959: The Year Everything Changed ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: J. Wiley & Sons. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-470-38781-8.

- Van Djik, Ruud (2008). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. 1. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 586. ISBN 978-0-415-97515-5.

- Kaplan (2009). 1959. p. 13.

- Newman, Kitty (2007). Macmillan, Khrushchev and the Berlin Crisis 1958–1960. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-415-35463-9.

- Leffler, Melvyn P. (2007). For the Soul of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Cold War. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-8090-9717-3.

- According to then Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Jacqueline Kennedy's message was much shorter and to the point: "My husband's dead. Now peace is up to you": Douglass, James W (2008). JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 380. ISBN 978-1-4391-9388-4.

- Taubman 2004, pp. 532–533.

- See Mikoyan, Sergo; Svetlana Savranskaya (ed.) The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis: Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Missiles of November. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012.

- Taubman 2004, pp. 580ff.

- Khrushchev, Sergei; Benson, Shirley (2008). Nikita Khrushchev and the Creation of a Superpower. 1. University Park, PA: Penn State Press. pp. 652–653. ISBN 978-0-271-02170-6.

- Savranskaya, Svetlana. "The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis: Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Missiles of November." George Washington University.

- Matthews, Joe. "Cuban Missile Crisis: The Other, Secret One." BBC News Magazine. 12 October 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- Staff writer (24 July 1964). "Russia: Successor Confirmed". Time: 1. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- Taubman 2004, pp. 3–17.

- Khrushchev, Nikita (2006). Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev: Reformer, 1945–1964. 2. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State Press. p. 700. ISBN 978-0-271-02332-8.

- Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise and Fall of Communism. New York: Ecco. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-06-113879-9.

- Staff writer (17 December 1965). "Russia: Kicks, Upstairs & Down". Time: 1. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 669.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 83n.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 52.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 12n., 43–44.

- "Controversial Soviet Leader's Statue in Yerevan an Exercise in Rewriting History?". Hetq. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- Poghosyan, Yekaterina (29 May 2014). "Stalin's Man Mikoyan to Get Statue in Yerevan". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- Jebeyan, Hripsime (4 June 2014). ""'Mikoyan's statue will not be erected, I am more than confident.' Hayk Demoyan"". Aravot. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- "The Death of Stalin".

Further reading

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anastas Mikoyan |

- Miklós, Kun. Stalin: An Unknown Portrait. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2003.

- Mikoyan, Anastas I. Memoirs of Anastas Mikoyan: The Path of Struggle, Vol 1. Trans. Katherine T. O'Connor and Diana L. Burgin. Madison, CT: Sphinx Press, 1988. ISBN 0-943071-04-6.

- Mikoyan, Stepan A. Memoirs of Military Test-Flying And Life with the Kremlin's Elite. Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 1999. ISBN 1-85310-916-9.

- Sebag-Montefiore, Simon (2005). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-7678-9.

- Taubman, William (2004). Khrushchev: The Man and His Era. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32484-6.

- Mikoyan family history Stas Namin site

External links

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Leonid Brezhnev |

Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet 1964–1965 |

Succeeded by Nikolai Podgorny |