North Borneo dispute

The North Borneo dispute, also known as the Sabah dispute, is the territorial dispute between Malaysia and the Philippines over much of the eastern part of the state of Sabah. Sabah is previously known as North Borneo prior to the formation of the Malaysian federation. The Philippines, presenting itself as the successor state of the Sultanate of Sulu, retains a "dormant claim" on Eastern Sabah on the basis that the territory was only leased to the British North Borneo Company in 1878, with the sovereignty of the Sultanate (and subsequently the Republic) over the territory never having been relinquished.[2] However, Malaysia considers this dispute as a "non-issue" as it interprets the 1878 agreement as that of cession[3] and that it deems that the residents of Sabah (including Eastern Sabah) had exercised their right to self-determination when they joined to form the Malaysian federation in 1963.[4]

1878 Agreement

_Sulu_(right)_Overbeck.jpg)

(Right) The second concession treaty was signed by Sultan Jamal ul-Azam of Sulu on 22 January 1878 also appointing Baron de Overbeck as Dato Bendahara and Raja Sandakan, approximately three weeks after signature of the first treaty.[6]

On 22 January 1878, the Sultanate of Sulu and a British commercial syndicate made up of Alfred Dent and Baron von Overbeck signed an agreement, which, depending on the translation used, stipulated that North Borneo was either ceded or leased to the British syndicate in return for a payment of 5,000 Malayan dollars per year.[7][8]

The 1878 agreement was written in Malay using the Jawi script, in which the contentious wordings are as follows:

sudah kuredhai pajakan dengan keredhaan dan kesukaan kita sendiri kepada tuan Gustavus Baron von Overbeck yang tinggal dalam negeri Hong Kong dan kepada Alfred Dent Esquire yang tinggal dalam negeri London... sampai selama-lamanya sekalian perintah dan kuasa yang kita punya yang takluk kepada kita di tanah besar Pulau Borneo dari Sungai Pandasan di sebelah barat sampai sepanjang semua tanah di pantai sebelah timur sejauh Sungai Sibuku di sebelah selatan.[9]

The keyword in the agreement is the ambiguous term pajakan, a Malay term which was translated by Spanish linguists in 1878 and by American anthropologists H. Otley Beyer and Harold Conklin in 1946 as "arrendamiento" or "lease".[10][11][12] However, the British used the interpretation of historian Najeeb Mitry Saleeby in 1908 and William George Maxwell and William Summer Gibson in 1924, which translated pajak as "grant and cede".[13][14][15][16]

It can be argued however, that "pajakan" means "mortgage" or "pawn" or even "wholesale", as per the contemporary meaning of "pajakan" in Sulu and Malay, which essentially means that the land is pawned in perpetuity for the annual cession money, and the sultanate would need to repay the entire infinite value of the territory to redeem it back.[17][18] Furthermore, the term "selama-lama" which means "forever" or "in perpetuity" indicate a binding effect beyond the lifetime of the then Sultan.

The ambiguity led to the different interpretation of the original Malay text, as shown in two versions below:

|

|

Throughout the British administration of North Borneo, the British government continued to make the annual "cession money" payment to the Sultan and its heir and these payments were expressly shown in the receipts as "cession money".[19] In a 1961 conference in London, during which a Philippine and British panel met to discuss on the Philippine claim of North Borneo, the British panel informed the Congressman Salonga that the wording of the receipts has not been challenged by the Sultan or its heir. [20]

During a meeting of Maphilindo between the Philippine, Malayan and Indonesian governments in 1963, the Philippine government said the Sultan of Sulu wanted the payment of 5,000 from the Malaysian government.[21] The first Malaysian Prime Minister at the time, Tunku Abdul Rahman said he would go back to Kuala Lumpur and get on the request.[21] Since then, the Malaysian Embassy in the Philippines had issued a check in the amount of 5,300 ringgit (US$1710 or about 77,000 Philippine pesos) to the legal counsel of the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu. These payments however have been stopped as of 2013.[22] Malaysia considers the amount an annual "cession" payment for the land, while the sultan’s descendants consider it "rent".[23]

The foregoing Sulu claim rests on the treaty signed by Sultan Jamalul Alam of Sulu appointing Baron de Overbeck as Dato Bendahara and Raja Sandakan on 22 January 1878. However, a further, earlier treaty signed by Sultan Abdul Momin of Brunei appointed Baron de Overbeck as the Maharaja Sabah, Rajah Gaya and Sandakan. This was signed on 29 December 1877, and granted the territories of Paitan as far as the Sibuco River,[24] which overlaps the Sulu Sultanate's claim of their dominion in Sabah. In 1877, the Brunei Sultanate still believed and maintained that the territory was under its control.[6]

Madrid Protocol

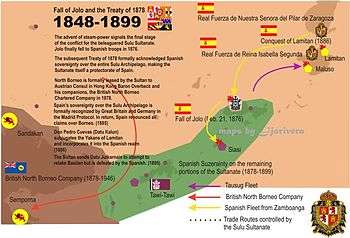

As attested to by the International Court of Justice, the Sultan of Sulu relinquished the sovereign rights over all his possessions in favour of Spain, based on the "Bases of Peace and Capitulation" signed by the Sultan of Sulu and the crown of Spain in Jolo on 22 July 1878.[25] The Sultan stayed on as ruler in protectorate status.[26]

In 1885, Great Britain, Germany and Spain signed the Madrid Protocol to cement Spanish influence over the islands of the Philippines. In the same agreement, Spain relinquished all claims to North Borneo which had belonged to the Sultanate in the past in favour of Great Britain.[27]

The Spanish Government renounces, as far as regards the British Government, all claims of sovereignty over the territories of the continent of Borneo, which belong, or which have belonged in the past to the Sultan of Sulu (Jolo), and which comprise the neighbouring islands of Balambangan, Banguey, and Malawali, as well as all those comprised within a zone of three maritime leagues from the coast, and which form part of the territories administered by the Company styled the "British North Borneo Company".

— Article III, Madrid Protocol of 1885

1903 Confirmation of Cession of certain island

On 22 April 1903, the successor of Sultan Jamalul Alam, Sultan Jamalul Kiram II, signed a document known as "Confirmation of cession of certain islands", under which he grant and ceded additional islands, in addition to the land agreed upon in 1878, in the vicinity of the mainland of North Borneo from Banggi Island to Sibuku Bay to British North Borneo Company.[28]

In the 1903 agreement, the ambiguous term "pajakan" was no longer used, but instead the phrase "kita telah keredhai menyerahkan kepada pemerintah British North Borneo" which literally means "we have willingly surrendered to the Government of British North Borneo" was used in the agreement, asserting the understanding of the Sulu Sultanate of that time of the meaning of the earlier agreement in 1878.[29]

The confirmatory deed of 1903 makes it known and understood between the two parties that the islands mentioned were included in the cession of the districts and islands mentioned on 22 January 1878 agreement. Additional cession money was set at 300 dollars a year with arrears due for past occupation of 3,200 dollars. The originally agreed 5,000 dollars increased to 5,300 dollars per year payable annually.[30][31][32][note 1]

Macaskie decision of 1939

_01.jpg)

In 1939, propriety claimants Dayang Dayang Hadji Piandao and eight other heirs filed a civil suit regarding the "cession money" payable to the heirs of Sultan of Sulu—the then incumbent Jamalul Kiram II having died childless in June 1936. Chief Justice C. F. C. Macaskie of the High Court of North Borneo ruled on the share entitlement of each claimant.[33]

This ruling has often been quoted by proponents of the Sulu Sultanate's claim as proof of North Borneo's acknowledgment of the sultan's ownership of the territory, although it was made solely to determine who as heir was entitled to the "cession money" of 5,300 Malaysian ringgit per year.

Philippine claim

The Sultanate of Sulu was granted the north-eastern part of the territory as a prize for helping the Sultan of Brunei against his enemies in 1658. However, on 22 July 1878, the Sultanate of Sulu relinquished the sovereign rights over all his possessions in favour of Spain, based on the "Bases of Peace and Capitulation" signed by the Sultan of Sulu and Spain in Jolo. The Spanish then claimed the area in northern Borneo but ending its claim soon under the Madrid Protocol of 1885 after the United Kingdom and Germany recognised its presence in the Philippine archipelago in return for the Spanish to stop interfering the British affairs in northern Borneo.[27] Once the protocol had been ratified, the British North Borneo Chartered company proceeded with the administration of North Borneo, and in 1888, North Borneo became a British protectorate.[35]

On 15 July 1946, the North Borneo Cession Order in Council, 1946, declared that the State of North Borneo is annexed to the British Crown, hence becoming a British colony.[36] In September 1946, F. B. Harrison, former American Governor-General of the Philippines, urged the Philippine Government to protest this proclamation. America posited the claim on the premise that Spain had never acquired sovereignty over North Borneo, and thus did not have the right to transfer claims of sovereignty over North Borneo to the United Kingdom in the Madrid Protocol of 1885.[37] This argument however, contradicts the treaty made between Spain and the Sultanate of Sulu in 1878, which expressly states that all of the territory of the Sultanate of Sulu is relinquished to Spain. Furthermore, the American view may be based on an erroneous interpretation of that part of the 1878 and the earlier 1836 treaties, that excluded North Borneo from the Sulu transfer to Spanish sovereignty (when in fact the exclusion merely referred to Spanish protection offered to the Sultan of Sulu in case he was attacked). The United States based government also refused to intervene in the dispute, officially maintaining a neutral stance on the matter and continuing to recognise Sabah as part of Malaysia. [38]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On 12 September 1962, during President Diosdado Macapagal's administration, the Philippine government claimed the territory of North Borneo, and the full sovereignty, title and dominion over it were "ceded" by the heirs of Sultan of Sulu, Muhammad Esmail E. Kiram I, to the Philippines.[40] The Philippines broke off diplomatic relations with Malaysia after the federation was formed with Sabah in 1963, but probably resumed relations unofficially through the Manila Accord, in which the Philippines made it clear that its position on the inclusion of North Borneo in the Federation of Malaysia was subject to the final outcome of the Philippine claim to North Borneo. The representatives of Indonesia and the Federation of Malaya seconded that the inclusion of North Borneo into the aforementioned Federation "would not prejudice either the claim or any right thereunder".[41] It was revealed later in 1968 that President Ferdinand Marcos was training a team of militants on Corregidor known as Operation Merdeka for infiltration into Sabah.[42] The plan failed as a result of the Jabidah massacre.[43][44] Diplomatic ties were resumed in 1989 and succeeding Philippine administrations have placed the claim in abeyance in the interests of pursuing cordial economic and security relations with Kuala Lumpur.

Republic Act 5446 in the Philippines, which took effect on 18 September 1968, regards Sabah as a territory "over which the Republic of the Philippines has acquired dominion and sovereignty".[45] On 16 July 2011, the Philippine Supreme Court ruled that the Philippine claim over Sabah is retained and may be pursued in the future.[46] To date, Malaysia maintains that the Sabah claim is a non-issue and non-negotiable, thereby rejecting any calls from the Philippines to resolve the matter in ICJ. Sabah authorities stated in 2009 that they see the claim made by the Philippines' Moro leader Nur Misuari to take Sabah to International Court of Justice (ICJ) as a non-issue and that they dismiss the claim.[47]

Attempts at withdrawing claim

At the ASEAN Summit on 4 August 1977, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos announced that the Philippines would take "definite steps to eliminate one of the burdens of ASEAN — the claim of the Philippine Republic to Sabah".[48][49] The statement, however was not followed through,[50] despite negotiations[51] and reassurances made by Marcos again in 1984 with Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad.[49]

A bill to repeal Republic Act 5446 was filed by Leticia Ramos Shahani in the Philippine Senate in 1987.[51] The bill was widely criticised for effectively dropping the country's claim over the territory. Muslim members of Congress also voiced their strong opposition to the measure for fears it would "endanger" the proprietary rights of the Sultanate of Sulu. This eventually led Shahani to not pursue the bill's passage.[52][53]

Formation of Malaysia

.djvu.jpg)

Prior to the formation of the Malaysia, two commissions of enquiry visited North Borneo, along with neighbouring Sarawak, to establish the state of public opinion there regarding merger with Malaya (and Singapore). The commission was mandated to address self-determination of the people of Sabah, i.e., the right of the people of Sabah to freely determine their own political status and freely pursue their own economic, social and cultural development. The first commission, usually known as the Cobbold Commission was established by the Malayan and British governments and was headed by Lord Cobbold, along with two representatives of Malaya and Britain (but neither of the territories under investigation). The Commission found that 'About one third of the population of each territory [i.e. of North Borneo and of Sarawak] strongly favours early realisation of Malaysia without too much concern over terms and conditions. Another third, many of them favourable to the Malaysia project, ask, with varying degrees of emphasis, for conditions and safeguards. The remaining third is divided between those who insist upon independence before Malaysia is considered and those who would strongly prefer to see British rule continue for some years to come'.[55] The Commission published its report on 1 August 1962 and had made several recommendations. Unlike in Singapore, however, no referendum was ever conducted in North Borneo and Sarawak.[56]

Indonesia and the Philippines rejected the findings of the Cobbold Commission. In 1963, a tripartite meeting was held in Manila between Indonesian president Sukarno, Philippines president Diosdado Macapagal and Malayan Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman. The three heads of state signed an agreement known as the Manila Accord, which stipulated that the inclusion of North Borneo as part of Malaysia would not prejudice either the claim or any right thereunder by the Philippines to the territory. It was further agreed to petition the UN to send another commission of enquiry and the Philippines and Indonesia agreed to drop their objection to the formation of Malaysia if the new commission found popular opinion in the territories in favour.

The UN Mission to Borneo was thus established, comprising members of the UN Secretariat from Argentina, Brazil, Ceylon, Czechoslovakia, Ghana, Pakistan, Japan and Jordan.[57] The Mission's report, authored by UN Secretary-General U Thant found ‘a sizeable majority of the people' in favour of joining Malaysia.[58][59] Indonesia and the Philippines subsequently rejected the report's findings – and Indonesia continued its semi-military policy of konfrontasi towards Malaysia.[60][61] The "referendum" did not involve the entire population of North Borneo and Sarawak at that time, but only representative consultations.[62] The UN mission report noted "(t)here was no reference to a referendum or plebiscite in the request..." and that "(t)he Mission accordingly arranged for consultations with the population through the elected representatives of the people, leaders of political parties and other groups and organisations, and with all persons who were willing to express their views".[63][64]

Related events

Sovereignty over Ligitan and Sipadan islands case

In 2002, in a case concerning sovereignty over Ligitan and Sipadan islands between Indonesia and Malaysia, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled in favour of Malaysia.[65] The two islands are located in the Celebes Sea off the northeast coast of Borneo. The case was decided based on Malaysia's effectivités (evidence of possession and use by a particular state that is effective to claim title) on the two islands as both Indonesia and Malaysia did not possess treaty-based titles on Ligitan and Sipadan.[66]

The Philippines applied to intervene in the case based on its territorial claim to North Borneo. Indonesia objected to the application and stated that the "Philippines raises no claim with respect to [the two islands] and maintains that the legal status of North Borneo is not a matter on which the Court has been asked to rule". Malaysia further contended that "the issue of sovereignty over Ligitan and Sipadan is completely independent of that of the status of North Borneo" and that "the territorial titles are different in the two cases".[66] The application was ultimately rejected by the ICJ because of the non-existence of an "interest of legal nature" such that the Court did not find how the decision on the case concerning the two islands would affect the Philippines' territorial claim to North Borneo.[67][68]

2013 Standoff

On 11 February 2013, a group of approximately 100–200 individuals, some of them armed, arrived by boat in Lahad Datu, Sabah from Simunul island, Tawi-Tawi in the southern Philippines.[69] They were sent by Jamalul Kiram III, one of the claimants to the throne of the Sultanate of Sulu. Their objective was to assert their unresolved territorial claim to North Borneo. During the ensuing standoff, 56 of his followers were killed, along with 6 civilians and 10 Malaysian soldiers.[70][71][72][73]

Diplomatic spat

Teddy Locsin Jr. @teddyboylocsin Replying to @USEmbassyPH

Sabah is not in Malaysia if you want to have anything to do with the Philippines.

July 27, 2020

Hishammuddin Hussein @HishammuddinH2O Replying to @Teddy Locsin Jr.

This is an irresponsible statement that affects bilateral ties. @MalaysiaMFA will summon the Philippines Ambassador on Monday to explain. Sabah is, and will always be, part of Malaysia.

July 29, 2020

On July 27, 2020, Philippine Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr. posted a tweet replying to a post from the US Embassy in Manila saying that Sabah does not belong to Malaysia. In response, the Malaysian Foreign Minister Hishammuddin Hussein rebuked the Philippine Foreign Secretary's tweet as an irresponsible statement that affects bilateral ties, and on July 30, 2020 summoned the Philippine ambassador. Locsin then summoned the Malaysian ambassador in a tit-for-tat move. [74]

In addition, former Sabah chief minister, Musa Aman, told the Philippines to back off from continuing its claim over the state, and stop using this type of narrative for its internal political purposes. Similarly, former Malaysia foreign minister, Anifah Aman, who is also a Sabahan, criticised Locsin for his statement. [75]

See also

References

- "British North Borneo company charter (page 4)". OpenLibrary.org. 1878. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- "East and Southeast Asia: the Philippines". CIA Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Campbell, Charlie (26 February 2013). "Sabah Standoff: Diplomatic Drama After Filipino Militants Storm Malaysia". TIME. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- James W. Gould (1969). The United States and Malaysia. Harvard University Press. pp. 106–. ISBN 978-0-674-92615-8.

- Rozan Yunos (21 September 2008). "How Brunei lost its northern province". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- Rozan Yunos (7 March 2013). "Sabah and the Sulu claims". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- International Court of Justice (2003). Summaries of Judgments, Advisory Opinions, and Orders of the International Court of Justice, 1997-2002. United Nations Publications. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-92-1-133541-5.

- Keat Gin Ooi (1 January 2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1163–. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- Hamdan Aziz (2016). "Tuntutan Kesultanan Sulu terhadap Sabah: Soroton dari Perspektif Sejarah dan Perundangan (The Claim Over Sabah by the Sultanate of Sulu: A Revision from Historical and Legal Perspective)" (PDF). Jurnal Antarabangsa Dunia Melayu (in Malay). 9: 284–285 – via Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

- "Translation by Professor Conklin of the Deed of 1878 in Arabic characters found by Mr. Quintero in Washington (Philippine Claim to North Borneo)". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 1. 1963. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- "Contrato de Arrendo de Sandacan en Borneo, con el Baron de Overbeck" (in Spanish). Philippine Claim to North Borneo, Vol. I. 13 July 1878. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- "Brief memorandum on the government of the Sultanate of Sulu and powers of the Sultan during the 19th century (The Philippine Claim to a Portion of North Borneo)". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 8 December 1946. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- British Government (1878). "British North Borneo Treaties. (British North Borneo, 1878)" (PDF). Sabah State Government (State Attorney-General's Chambers). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- Najeeb Mitry Saleeby (1908). The History of Sulu. Ethnological Survey for Philippine Islands (Illustrated ed.). Bureau of Printing, Harvard University. pp. 225–233. OCLC 3550427. Retrieved 31 March 2013 – via Internet Archive.

- Maxwell, Willian George & Gibson, Willian Summer (1998). Treaties and Engagements Affecting the Malay States and Borneo. J. Truscott & Son, Limited. p. 205. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- "1878 Grant of Lease by the Sultan of Sulu to Britain: Profession Conklin Translation vis a vis Maxwell and Gibson Translation". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- Mohamed Ariff (1991). The Muslim Private Sector in Southeast Asia: Islam and the Economic Development of Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-981-3016-09-5.

- K.J. Allison (1979). "English Pilipino Sama Sibutu', BASIC VOCABULARY" (PDF). SUMMER INSTITUTE OF LINGUISTICS-Philippines, Inc., TRANSLATORS. p. 59. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- "Philippine Claim to North Borneo, Volume 2". Bureau of Printing. 1967. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Philippine Claim to North Borneo, Volume 2". Bureau of Printing. 1967. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Why 'Sultan' is dreaming". Daily Express. 27 March 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- "Malaysia stopped paying cession money to Sulu Sultanate in 2013". New Straits Times. 23 July 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "WHAT WENT BEFORE: Sultan of Sulu's 9 principal heirs". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 23 February 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- British Government (1877). "British North Borneo Treaties. (British North Borneo, 1877)" (PDF). Sabah State Government (State Attorney-General's Chambers). Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- International Court of Justice (2003). Summaries of Judgments, Advisory Opinions, and Orders of the International Court of Justice, 1997-2002. United Nations Publications. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-92-1-133541-5.

- • "Protocol between Spain and Sulu confirming the Bases of Peace and Capitulation etc., signed at Jolo". Oxford Historical Treaties. 22 July 1878. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

• "Case Concerning of Sovereignty of Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan (Indonesia/Malaysia) [Memorial of Malaysia]" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 2 November 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

• Raymond Tombung (8 March 2013). "Sabah claim: A tale of two versions". Free Malaysia Today. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

• "The last treaty between the Sultanate of Sulu and Spain, the Treaty of July 1878". Kahimyang. 21 July 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

• British and Foreign State Papers. H.M. Stationery Office. 1888. pp. 1106–. - British Government (1885). "British North Borneo Treaties. (British North Borneo, 1885)" (PDF). Sabah State Government (State Attorney-General's Chambers). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- R. Haller-Trost (1 January 1998). The Contested Maritime and Territorial Boundaries of Malaysia: An International Law Perspective. Kluwer Law International. ISBN 978-90-411-9652-1.

- Haller-Trost, R (1998). The Contested Maritime and Territorial Boundaries of Malaysia: An International Law Perspective. University of Michigan: Kluwer Law International. p. 155. ISBN 9789041196521.

- Guenther Dahlhoff (June 2012). Bibliographic Set (2 Vol Set). International Court of Justice, Digest of Judgments and Advisory Opinions, Canon and Case Law 1946 - 2011. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 1133–. ISBN 978-90-04-23062-0.

- British Government (1903). "British North Borneo Treaties. (British North Borneo, 1903)" (PDF). Sabah State Government (State Attorney-General's Chambers). Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- Office of the President of the Philippines (2013). "CONFIRMATION by Sultan of Sulu of Cession of Certain Islands". Government of the Philippines. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Rodolfo Severino (2011). Where in the World is the Philippines?: Debating Its National Territory. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-981-4311-71-7.

- Mohamad, Kadir (2009). "Malaysia's territorial disputes – two cases at the ICJ : Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore), Ligitan and Sipadan [and the Sabah claim] (Malaysia/Indonesia/Philippines)" (PDF). Institute of Diplomacy and Foreign Relations (IDFR), Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Malaysia: 46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

Map of British North Borneo, highlighting in yellow colour the area covered by the Philippine claim, presented to the Court by the Philippines during the Oral Hearings at the ICJ on 25 June 2001

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Olson, James Stuart; Shadle, Robert (1996). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 192–. ISBN 978-0-313-29366-5.

- "The North Borneo Cession Order in Council 1946". Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines. 10 July 1946 – via gov.ph. (effective as of 15 July 1946)

- Severino, Rodolfo (2011). Where in the World is the Philippines?: Debating Its National Territory. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-981-4311-71-7.

- Hawkins, Michael Gary (2008). Co-producing the Postcolonial: U.S.-Philippine Cinematic Relations, 1946--1986. pp. 350–. ISBN 978-0-549-89836-8.

- "PHILIPPINES and MALAYSIA" (PDF). UN.org. United Nations. 1967. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- "Cession and transfer of the territory of North Borneo by His Highness, Sultan Mohammad Esmail Kiram, Sultan of Sulu, acting with the consent and approval of the Ruma Bechara, in council assembled, to the Republic of the Philippines". gov.ph. Government of the Philippines. 24 April 1962. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Treaties and international agreements registered or filed and recorded with the Secretariat of the United Nations" (PDF). United Nations. 1967. p. 362. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- "Marcos order: Destabilize, take Sabah". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 2 April 2000. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Whitman, Paul F. (2002). "The Corregidor Massacre - 1968". Corregidor Historic Society. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Latiph, Acram (13 March 2013). "Sabah – the question that won't go away". New Mandala. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- "An Act to Amend Section One of Republic Act Numbered Thirty Hundred and forty-six, Entitled "An Act to Define the Baselines of the Territorial Sea of the Philippines" [Approved: 18 September 1968]". Philippine Laws and Jurisprudence Databank. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- "G.R No. 187167". Supreme Court of the Philippines. 16 July 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- "Call for ICJ arbitration dismissed". The Star. 29 May 2008. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- Richardson, Michael (5 August 1977). "Marcos drops Philippine claim to Sabah". The Age. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- "President Ferdinand Marcos said today he had proposed talks..." United Press International. 24 February 1984. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- Francisco Tatad (15 February 2017). "KL may now agree to talk, shall we go for it?". The Manila Times. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Quezon, Manuel L. III (2 March 2013). "North Borneo (Sabah): An annotated timeline 1640s-present". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Tordesillas, Ellen (19 February 2013). "'Bizarre' standoff in Sabah". Yahoo News! Philippines. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- de Castro Jr., Isagani (2010). N Ganesan; Ramses Amer (eds.). International Relations in Southeast Asia: Between Bilateralism and Multilateralism. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 232. ISBN 978-9814279574.

- "PHILIPPINES, FEDERATION OF MALAYA and INDONESIA" (PDF). United Nations. 1965. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- Report of the Commission of Enquiry: North Borneo and Sarawak, 1962, HMSO, 1962

- Luke Rintod (8 March 2013). "There was no Sabah referendum". Free Malaysia Today. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Philip Mathews (28 February 2014). Chronicle of Malaysia: Fifty Years of Headline News, 1963-2013. Editions Didier Millet. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-967-10617-4-9.

- Thomas R. Mockaitis (1995). British Counterinsurgency in the Post-imperial Era. Manchester University Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-7190-3919-5.

- Bradley R. Simpson (28 March 2008). Economists with Guns: Authoritarian Development and U.S.-Indonesian Relations, 1960-1968. Stanford University Press. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-0-8047-7952-4.

- George McTurnan Kahin (2003). Southeast Asia: A Testament. Psychology Press. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-0-415-29976-3.

- Andrew W. Cordier; U. Thant (1 June 2010). Public Papers of the Secretaries General of the United Nations: Volume 7 U. Thant 1965-1967. Columbia University Press. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-0-231-51381-4.

- Evan Luard (27 July 2016). A History of the United Nations: Volume 2: The Age of Decolonization, 1955–1965. Springer. pp. 350–. ISBN 978-1-349-20030-6.

- A. J. Stockwell; University of London. Institute of Commonwealth Studies (2004). Malaysia. The Stationery Office. pp. 574–. ISBN 978-0-11-290581-3.

- Andrew W. Cordier; Max Harrelson (1 June 2010). Public Papers of the Secretaries General of the United Nations. Columbia University Press. pp. 399–. ISBN 978-0-231-51380-7.

- "The Court finds that sovereignty over the islands of Ligitan and Sipadan belongs to Malaysia". International Court of Justice. 17 December 2002. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan (Indonesia/Malaysia)". International Court of Justice. 17 December 2002. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "Sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan (Indonesia v. Malaysia) (Permission to Intervene by the Philippines)" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 23 October 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- "Sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan (Indonesia/Malaysia), Application for Permission to Intervene, Judgment" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 23 October 2001. p. 575. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "Heirs of Sultan of Sulu pursue Sabah claim on their own". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 16 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- Mike Frialde (23 February 2013). "Sultanate of Sulu wants Sabah returned to Phl". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- "Kronologi pencerobohon Lahad Datu" (in Malay). Astro Awani. 15 February 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "Dakwaan anggota tentera terbunuh hanya taktik musuh - Panglima Tentera Darat" (in Malay). Astro Awani. 12 August 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- Najiah Najib (30 December 2013). "Lahad Datu invasion: A painful memory of 2013". Astro Awani. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- "Malaysia, Philippines in war of words over Sabah claim". Al Jazeera English. 30 July 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Ex-chief minister Musa Aman slams Philippines over Sabah claim". The Straits Times. 1 August 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

Notes

- The Confirmatory Deed of 1903 must be viewed in the light of the 1878 Agreement. The British North Borneo Company entered into a Confirmatory Deed with the Sultanate of Sulu in 1903, thereby confirming and ratifying what was done in 1878.

Bibliography

- Manila Accord (31 July 1963)

- Exchange of notes constituting an agreement relating to the implementation of the Manila Accord of 31 July 1963

- Malaysia Act 1963

- Agreement relating to Malaysia between United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore

- Cabinet Memorandum. Policy in regard to Malaya and Borneo. Memorandum by the Secretary of State for the Colonies. 29 August 1945

Further reading

Allen, J. de V.; Stockwell, Anthony J. (1980). Wright., Leigh R. (ed.). A collection of treaties and other documents affecting the states of Malaysia 1761-1963. Oceana Pubns. ISBN 978-0-379-00781-7.