Anti-Azerbaijani sentiment in Armenia

The anti-Azerbaijani sentiment in Armenia has been mainly rooted in the unresolved territorial conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. According to a 2012 opinion poll, 63% of Armenians perceive Azerbaijan as "the biggest enemy of Armenia" while 94% of Azerbaijanis consider Armenia to be "the biggest enemy of Azerbaijan."[1]

Early period

In the early 20th century the Transcaucasian Armenians began to equate the Azerbaijani people with the perpetrators of anti-Armenian policies such as the Armenian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire.[2]

Soon afterwards a wave of anti-Azerbaijani massacres in both Azerbaijan and Armenia started in 1918 and continued until 1920. First in March 1918, a massacre of the Azerbaijanis in Baku took place. An estimated of 3,000 to 10,000 Azerbaijanis were killed by nationalist Dashnak Armenians, orchestrated by the Bolshevist Stepan Shahumyan. The massacre was later called the March Days.

During the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

After the Nagorno-Karabakh War anti-Azerbaijani sentiment grew in Armenia, leading to harassment of Azerbaijanis there.[3] In the beginning of 1988 the first refugee waves from Armenia reached Baku. In 1988, Azerbaijanis and Kurds (around 167,000 people) were expelled from the Armenian SSR.[4] Following the Karabakh movement, initial violence erupted in the form of the murder of both Armenians and Azerbaijanis and border skirmishes.[5] As a result of these pogroms, Armenians have killed 214 Azerbaijanis and ethnically cleansed Azerbaijanis from all territory of Armenia between 1987 and 1990.[6]

On June 7, 1988 Azerbaijanis were evicted from the town of Masis near the Armenian–Turkish border, and on June 20 five Azerbaijani villages were cleansed in the Ararat Province.[7] Henrik Pogosian was ultimately forced to retire, blamed for letting nationalism develop freely.[7] Although purges of the Armenian and Azerbaijani party structures were made against those who had fanned or not sought to prevent ethnic strife, as a whole, the measures taken are believed to be meager.[7]

The year 1993 was marked by the highest wave of the Azerbaijani internally displaced persons, when the Karabakh Armenian forces occupied territories beyond the Nagorno-Karabakh borders.[8] The Karabakhi Armenians ultimately succeeded in removing Azerbaijanis from Nagorno-Karabakh.

After Nagorno-Karabakh War

On January 16, 2003 Robert Kocharian said that Azerbaijanis and Armenians were "ethnically incompatible"[9] and it was impossible for the Armenian population of Karabakh to live within an Azerbaijani state.[10] Speaking on 30 January in Strasbourg, Council of Europe Secretary-General Walter Schwimmer said Kocharian's comment was tantamount to warmongering. Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe President Peter Schieder said he hopes Kocharian's remark was incorrectly translated, adding that "since its creation, the Council of Europe has never heard the phrase "ethnic incompatibility"".[10]

In 2010 an initiative to hold a festival of Azerbaijani films in Yerevan was blocked due to popular opposition. Similarly, in 2012 a festival of Azerbaijani short films, organized by the Armenia-based Caucasus Center for Peace-Making Initiatives and supported by the U.S. and British embassies, which was scheduled to open on April 12, was canceled in Gyumri after protesters blocked the festival venue.[11][12]

On September 2 2015, the Minister of Justice Arpine Hovhannisyan on her personal Facebook page shared an article link featuring her interview with the Armenian news website Tert.am where she condemned the sentencing of an Azerbaijani journalist and called the human rights situation in Azerbaijan "appalling". Subsequently the minister came under criticism for liking a racist comment on the aforementioned facebook post by Hovhannes Galajyan, editor-in-chief of local Armenian newspaper Iravunk; On the post, Galajyan had commented in Armenian: “What human rights when even purely biologically a Turk cannot be considered a human".

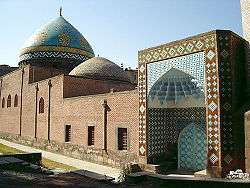

Destruction of mosque in Armenia

In 1990 a mosque in Yerevan was pulled down with a bulldozer.[13][14] The Blue Mosque is the only one that remains in present-day Yerevan.

In the opinion of Thomas de Waal, the destruction of a mosque in Armenia was facilitated by a linguistic sleight of hand, as the name “Azeri” or “Azerbaijani” was not in common usage before the twentieth century, and these people were referred to as “Tartars”, “Turks” or simply “Muslims”. Azerbaijanis are being written out of the history of Armenia, and Armenians refer to Muslim monuments as "Persian", even though the worshippers in a mosque built in 1760 would have been Turkic-speaking Shiite subjects of Safavid dynasty, i.e. the ancestors of Azerbaijanis.[15]

See also

- List of anti-Azerbaijani massacres

- Anti-Armenianism in Azerbaijan

References

- "The South Caucasus Between The EU And The Eurasian Union" (PDF). Caucasus Analytical Digest #51-52. Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen and Center for Security Studies, Zürich. 17 June 2013. p. 21. ISSN 1867-9323. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- Croissant, Michael (1998). The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict: Causes and Implications. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 8. ISBN 0275962415.

- Cornell, Svante (2010). Azerbaijan Since Independence. M.E. Sharpe. p. 48. ISBN 0765630036.

- Barrington, p. 230

- Barrington, Lowell (2006). After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial & Postcommunist States. University of Michigan Press. p. 231. ISBN 0472068989.

- Окунев, Дмитрий. "«Меня преследует этот запах»: 30 лет армянским погромам в Баку". Газета.Ru (in Russian). Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Svante E. Cornell (1999). "The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict" (PDF). Silkroadstudies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Geukjian, Ohannes (2012). Ethnicity, Nationalism and Conflict in the South Caucasus: Nagorno-Karabakh and the Legacy of Soviet Nationalities Policy. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 199. ISBN 1409436306.

- Rferl.org: Nagorno-Karabakh: Timeline Of The Long Road To Peace

- "Newsline". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. February 3, 2003. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "Azerbaijani Film Festival Canceled In Armenia After Protests". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. April 13, 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Soghoyan, Yeranuhi (April 11, 2012). "Gyumri Mayor Permits Anti-Azerbaijani Film Protest; Bans Local Environmentalists". Hetq online. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- Robert Cullen, A Reporter at Large, “Roots,” The New Yorker, April 15, 1991, p. 55

- Thomas De Waal. Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war. NYU Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7, ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9, p. 79.

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war. New York University Press. p. 80.

That the Armenians could erase an Azerbaijani mosque inside their capital city was made easier by a linguistic sleight of hand: the Azerbaijanis of Armenia can be more easily written out of history because the name “Azeri” or “Azerbaijani” was not in common usage before the twentieth century. In the premodern era these people were generally referred to as “Tartars”, “Turks” or simply “Muslims”. Yet they were neither Persians nor Turks; they were Turkic-speaking Shiite subjects of Safavid dynasty of the Iranian Empire – in other words, the ancestors of people, whom we would now call “Azerbaijanis”. So when the Armenians refer to the “Persian mosque” in Yerevan, the name obscures the fact that most of the worshippers there, when it was built in the 1760s, would have been, in effect, Azerbaijanis.