1947–1949 Palestine war

The 1947–1949 Palestine war,[lower-alpha 1] known in Israel as the War of Independence (Hebrew: מלחמת העצמאות, Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut) and in Arabic as The Nakba (lit. Catastrophe, Arabic: النكبة, al-Nakba),[13][14][15] was fought in the territory of Palestine under the British Mandate. It is the first war of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the broader Arab–Israeli conflict. During this war, the British Empire withdrew from Mandate Palestine, which had been a province (eyalet) of the Ottoman Empire before British occupation in 1917. The war culminated in the establishment of the State of Israel by the Jews, and saw the complete demographic transformation of Palestine, with the displacement of around 700,000 Palestinian Arabs and the complete destruction of most of their villages, towns and cities.[16] The Palestinian Arabs ended up stateless, displaced either to the Palestinian territories captured by Egypt and Jordan or to the surrounding Arab states; many of them, as well as their descendants, remain stateless and in refugee camps. The territory that was under British administration before the war was divided between the State of Israel, which captured about 78% of it, the Kingdom of Jordan (then known as Transjordan), which captured and later annexed the area that became the West Bank, and Egypt, which captured the Gaza Strip, a coastal territory on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, in which it established the All-Palestine Government.

| 1947–1949 Palestine war | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab–Israeli conflict | |||||||||

Arab fighters near a burnt armoured Haganah supply truck, near Jerusalem | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Before 26 May 1948 After 26 May 1948:

Foreign volunteers: Mahal |

Foreign volunteers: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Israel: c. 10,000 initially, rising to 115,000 by March 1949 |

Arabs: c. 2,000 initially, rising to 70,000, of which: Egypt: 10,000 initially, rising to 20,000 Iraq: 3,000 initially, rising to 15,000–18,000 Syria: 2,500–5,000 Transjordan: 8,000 – 12,000 Lebanon: 1,000[7] Saudi Arabia: 800–1,200 Arab Liberation Army: 3,500–6,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 6,080 killed (about 4,074 troops and 2,000 civilians)[8] | Between +5,000[8] and 20,000 (inc civilians)[9] among which 4,000 soldiers for Egypt, Jordan and Syria[10] | ||||||||

| 15,000 Arab dead and 25,000 wounded (estimate)[11] | |||||||||

The war had two main phases. The first phase is the 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine. It began on 30 November 1947,[17] a day after the United Nations voted to divide the territory of Palestine into Jewish and Arab sovereign states, and an international Jerusalem (UN Resolution 181). The Jewish leadership accepted the plan, but the Palestinian Arab leaders, as well as the Arab states, unanimously opposed it and conflict soon began.[18] This phase of the war is described by historians as the "civil", "ethnic" or "intercommunal" war, as it was fought mainly between Jewish and Palestinian Arab militias, supported by the Arab Liberation Army and the surrounding Arab states. Characterised by guerrilla warfare and terrorism, it escalated at the end of March 1948 when the Jews went on the offensive, and concluded with their defeating the Palestinians in major campaigns and battles, establishing clear frontlines. During this period the British still maintained a declining rule over Palestine and occasionally intervened in the violence.[19][20]

The British Empire scheduled its withdrawal and abandonment of all claims to Palestine for 14 May 1948. On that date, when the last remaining British troops and personnel were on departure at the city of Haifa, the Jewish leadership in Palestine declared the establishment of the State of Israel. This declaration was followed by the immediate invasion of Palestine by the surrounding Arab armies and expeditionary forces in order to prevent the establishment of Israel and to aid the Palestinian Arabs, who were on the losing side at that point, with a large portion of their population already fleeing or being forced out by the Jewish militias. The invasion marked the beginning of the second phase of the war, the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The Egyptians advanced on the southern coastal strip and were halted near Ashdod; the Jordanian Arab Legion and Iraqi forces captured the central highlands of Palestine. Syria and Lebanon fought several skirmishes with the Israeli forces in the north. The Jewish militias, organised into the Israel Defense Forces, managed to halt the Arab forces. The following months saw fierce fighting between the IDF and the Arab armies, which were being slowly pushed back. The Jordanian and Iraqi armies managed to maintain control over most of the central highlands of Palestine and capture East Jerusalem, including the Old City. Egypt's occupation zone was limited to the Gaza Strip and a small pocket surrounded by Israeli forces at Al-Faluja. In October and December 1948, Israeli forces crossed into Lebanese territory and pushed into Egypt's Sinai Peninsula, encircling the Egyptian forces near Gaza City. The last military activity happened in March 1949, when Israeli forces captured the Negev desert and reached the Red Sea. In 1949, Israel signed separate armistices with Egypt on 24 February, Lebanon on 23 March, Transjordan on 3 April, and Syria on 20 July. During this period the flight and expulsion of the Palestinian Arabs continued.

In the three years following the war, about 700,000 Jews immigrated to Israel from Europe and Arab lands, with one third of them having left or been expelled from their countries of residence in the Middle East.[21][22][23] These refugees were absorbed into Israel in the One Million Plan.[24][25][26][27]

Background

The 1948 War was the outcome of more than 60 years of friction between Jews and Arabs who inhabited the land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. The land is called "Eretz Yisrael" or "Land of Israel" by the Jews, and "Falastin" or "Palestine" by the Arabs. It is the birthplace of the Jewish people and Judaism. Through history, the territory has had many conquerors. One of these was the Roman Empire, which crushed a Jewish revolt during the second century, sacked Jerusalem and changed the land's name from Judaea to Palaestina, meaning "land of the Philistines", a nation that occupied the southern shore of the land in ancient times.

After the Romans came the Byzantines, Early Arab Caliphates, Crusaders, Muslim Mamluks and the Ottoman Empire. By 1881, the land was ruled directly from the Ottoman capital. It had a population of about 450,000 Arabic speakers, 90% of them Muslim, the rest Christian and Druze. Some 80% of the Arabs lived in 700 to 800 villages and the rest in a dozen towns. There were 25,000 Jews, who constituted the "Old Yishuv" (yishuv means "settlement" but referred to the Jewish inhabitants of Palestine). Most of them lived in Jerusalem and were ultra-Orthodox and poor. They had no nationalistic views.[28]

Jewish immigration to Palestine

Zionism formed in Europe as the national movement of the Jewish people. It sought to reestablish Jewish statehood in the ancient homeland. The first wave of Zionist immigration, dubbed the First Aliyah, lasted from 1882 to 1903. Some 30,000 Jews, mostly from the Russian Empire, reached Ottoman Palestine. They were driven both by the Zionist idea and by the wave of Antisemitism in Europe, especially in the Russian Empire, which came in the form of brutal pogroms. They wanted to establish Jewish agricultural settlements and a Jewish majority in the land that would allow them to gain statehood. They settled mostly the sparsely populated lowlands, which were swampy and subjected to Bedouin robbers.[29]

The Arab inhabitants of Ottoman Palestine who saw the Zionist Jews settle next to them had no national affiliation. They saw themselves as subjects of the Ottoman Empire, members of the Islamic community and as Arabs, geographically, linguistically and culturally. Their strongest affiliation was their clan, family, village or tribe. There was no Arab or Palestinian Arab nationalist movement. In the first two decades of Zionist immigration, most of the opposition came from the wealthy landowners and noblemen who feared they would have to fight the Jews for the land in the future.[30]

By 1914 the Jewish population of Ottoman Palestine was between 60,000 and 85,000, two-thirds of them members of the Zionist movement, mostly living in 40 new settlements. They encountered very little violence in the form of feuds and conflict over land and resources with their Arab neighbours or criminal activity. Between 1909 and 1914 this changed, as Arabs killed 12 Jewish settlement guards and Arab nationalism and opposition to the Zionist enterprise increased. In 1911, Arabs attempted to thwart the establishment of a Jewish settlement in the Jezreel Valley, and the dispute resulted in the death of one Arab man and a Jewish guard. The Arabs called the Jews the "new Crusaders", and anti-Zionist rhetoric flourished.[31] Tensions between Arabs and Jews led to violent disturbances on several occasions, notably in 1920, 1921, 1929 and 1936–1939.

World War I

During the war, Palestine served as the frontline between the Ottoman Empire and the British Empire in Egypt. The war briefly halted Jewish-Arab friction. The British invaded the land in 1915 and 1916 after two unsuccessful Ottoman attacks on Sinai. They were assisted by the Arab tribes in Hejaz, led by the Hashemites, and promised them sovereignty over the Arab areas of the Ottoman Empire. Palestine was omitted from the promise, first planned to be a joint British-French domain, and after the Balfour Declaration in November 1917, a "national home for the Jewish people". The decision to support Zionism was driven by Zionist lobbying, led by Chaim Weizmann. Many of the British officials who supported the decisions supported Zionism for religious and humanitarian reasons. They also believed that a British-backed state would help defend the Suez Canal.[32]

The Arab states

Following World War II, the surrounding Arab states were emerging from mandatory rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan in 1949, but remained under heavy British influence. Egypt gained nominal independence in 1922, but Britain continued to exert a strong influence on it until the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 limited Britain's presence to a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal until 1945. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops did not withdraw until 1946, the same year Syria won its independence from France.

In 1945, at British prompting, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Transjordan, and Yemen formed the Arab League to coordinate policy among the Arab states. Iraq and Transjordan coordinated closely, signing a mutual defence treaty, while Egypt, Syria, and Saudi Arabia feared that Transjordan would annex part or all of Palestine and use it as a stepping stone to attack or undermine Syria, Lebanon, and the Hijaz.[33]

The 1947 UN Partition Plan

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution "recommending to the United Kingdom, as the mandatory Power for Palestine, and to all other Members of the United Nations the adoption and implementation, with regard to the future government of Palestine, of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union", UN General Assembly Resolution 181(II).[34] This was an attempt to resolve the Arab-Jewish conflict by partitioning Palestine into "Independent Arab and Jewish States and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem". Each state would comprise three major sections; the Arab state would also have an enclave at Jaffa in order to have a port on the Mediterranean.

With about 32% of the population, the Jews were allocated 56% of the territory. It contained 499,000 Jews and 438,000 Arabs and most of it was in the Negev desert.[35] The Palestinian Arabs were allocated 42% of the land, which had a population of 818,000 Palestinian Arabs and 10,000 Jews. In consideration of its religious significance, the Jerusalem area, including Bethlehem, with 100,000 Jews and an equal number of Palestinian Arabs, was to become a Corpus Separatum, to be administered by the UN.[36] The residents in the UN-administered territory were given the right to choose to be citizens of either of the new states.[37]

The Jewish leadership accepted the partition plan as "the indispensable minimum,"[38] glad to gain international recognition but sorry that they did not receive more.[39] The representatives of the Palestinian Arabs and the Arab League firmly opposed the UN action and rejected its authority in the matter, arguing that the partition plan was unfair to the Arabs because of the population balance at that time.[40] The Arabs rejected the partition, not because it was supposedly unfair, but because their leaders rejected any form of partition.[41][42] They held "that the rule of Palestine should revert to its inhabitants, in accordance with the provisions of [...] the Charter of the United Nations."[43] According to Article 73b of the Charter, the UN should develop self-government of the peoples in a territory under its administration. In the immediate aftermath of the UN's approval of the partition plan, explosions of joy in the Jewish community were counterbalanced by discontent in the Arab community. Soon after, violence broke out and became more prevalent. Murders, reprisals, and counter-reprisals came fast upon each other, resulting in dozens killed on both sides. The sanguinary impasse persisted as no force intervened to put a stop to the escalating violence.

1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine

The first phase of the war took place from the United Nations General Assembly vote for the Partition Plan for Palestine on 29 November 1947 until the termination of the British Mandate and Israeli proclamation of statehood on 14 May 1948.[44] During this period the Jewish and Arab communities of British Mandate clashed, while the British organised their withdrawal and intervened only occasionally. In the first two months of the Civil War, around 1,000 people were killed and 2,000 injured,[45] and by the end of March, the figure had risen to 2,000 dead and 4,000 wounded.[46] These figures correspond to an average of more than 100 deaths and 200 casualties per week in a population of 2,000,000.

From January onwards, operations became increasingly militarised. A number of Arab Liberation Army regiments infiltrated Palestine, each active in a variety of distinct sectors around the coastal towns. They consolidated their presence in Galilee and Samaria.[47] The Army of the Holy War, under Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni's command, came from Egypt with several hundred men. Having recruited a few thousand volunteers, al-Husayni organised the blockade of the 100,000 Jewish residents of Jerusalem.[48]

To counter this, the Yishuv authorities tried to supply the city with convoys of up to 100 armoured vehicles, but the operation became more and more impractical as the number of casualties in the relief convoys surged. By March, al-Husayni's tactic had paid off. Almost all of Haganah's armoured vehicles had been destroyed, the blockade was in full operation, and hundreds of Haganah members who had tried to bring supplies into the city were killed.[49] The situation for those in the Jewish settlements in the highly isolated Negev and North of Galilee was more critical.

This caused the US to withdraw its support for the Partition plan, and the Arab League began to believe that the Palestinian Arabs, reinforced by the Arab Liberation Army, could end the partition. The British decided on 7 February 1948 to support Transjordan's annexation of the Arab part of Palestine.[50]

While the Jewish population was ordered to hold their ground everywhere at all costs,[51] the Arab population was disrupted by general conditions of insecurity. Up to 100,000 Arabs from the urban upper and middle classes in Haifa, Jaffa and Jerusalem, or Jewish-dominated areas, evacuated abroad or to Arab centres to the east.[52]

David Ben-Gurion ordered Yigal Yadin to plan for the announced intervention of the Arab states. The result of his analysis was Plan Dalet, which was put in place at the start of April.

Plan Dalet and second stage

The adoption of Plan Dalet marked the war's second phase, in which Haganah took the offensive.

The first operation, Nachshon, was directed at lifting the blockade on Jerusalem.[53] In the last week of March, 136 supply trucks had tried to reach Jerusalem; only 41 had made it. The Arab attacks on communications and roads had intensified. The convoys' failure and the loss of Jewish armoured vehicles had shaken the Yishuv leaders' confidence.

1,500 men from Haganah's Givati brigade and Palmach's Harel brigade conducted sorties to free up the route to the city between 5 April and 20 April. The operation was successful, and two months' worth of foodstuffs were trucked into Jerusalem for distribution to the Jewish population.[54] The operation's success was aided by al-Husayni's death in combat.

During this time, and independently of Haganah or Plan Dalet, irregular troops from Irgun and Lehi formations massacred 107 Arabs at Deir Yassin. The event was publicly deplored and criticised by the principal Jewish authorities and had a deep effect on the Arab population's morale. At the same time, the first large-scale operation of the Arab Liberation Army ended in a debacle, as they were roundly defeated at Mishmar HaEmek.[55] Their Druze allies left them through defection.[56]

Within the framework of creating Jewish territorial continuity according to Plan Dalet, the forces of Haganah, Palmach and Irgun intended to conquer mixed zones of population. Tiberias, Haifa, Safed, Beisan, and Jaffa were taken before the end of the Mandate, with Acre falling shortly after. More than 250,000 Palestinian Arabs fled these locales.[57]

The British had essentially withdrawn their troops. The situation pushed the neighbouring Arab states to intervene, but their preparation was not completed, and they could not assemble sufficient forces to turn the tide of the war. The majority of Palestinian Arab hopes lay with the Arab Legion of Transjordan's monarch, King Abdullah I. He did not intend to create a Palestinian Arab-run state, as he hoped to annex much of Mandatory Palestine. Playing both sides, he was in contact with the Jewish authorities and the Arab League.

Preparing for Arab intervention from neighbouring states, Haganah successfully launched Operations Yiftah[58] and Ben-'Ami[59] to secure the Jewish settlements of Galilee, and Operation Kilshon. This created an Israeli-controlled front around Jerusalem. The inconclusive meeting between Golda Meir and Abdullah I, followed by the Kfar Etzion massacre on 13 May by the Arab Legion, led to predictions that the battle for Jerusalem would be merciless.

Course of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

Arab Invasion

On 14 May 1948, the day before the expiration of the British Mandate, David Ben-Gurion declared the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.[60] Both superpower leaders, U.S. President Harry S. Truman and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, immediately recognised the new state, while the Arab League refused to accept the UN partition plan, proclaimed the right of self-determination for the Arabs across the whole of Palestine, and maintained that the absence of legal authority made it necessary to intervene to protect Arab lives and property.[61]

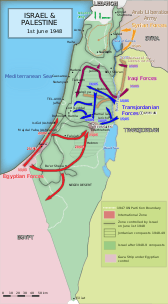

Over the next few days, contingents of four of the seven countries of the Arab League at that time, Egypt, Iraq, Transjordan, and Syria, invaded the former British Mandate of Palestine and fought the Israelis. They were supported by the Arab Liberation Army and corps of volunteers from Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Yemen. The Arab armies launched a simultaneous offensive on all fronts: Egyptian forces invaded from the south, Jordanian and Iraqi forces from the east, and Syrian forces invaded from the north. Cooperation among the various Arab armies was poor.

First truce: 11 June – 8 July 1948

The UN declared a truce on 29 May, which began on 11 June and lasted 28 days. The ceasefire was overseen by UN mediator Folke Bernadotte and a team of UN Observers, army officers from Belgium, United States, Sweden and France.[62] Bernadotte was voted in by the General Assembly to "assure the safety of the holy places, to safeguard the well being of the population, and to promote 'a peaceful adjustment of the future situation of Palestine'".[63] He spoke of "peace by Christmas" but saw that the Arab world had continued to reject the existence of a Jewish state, whatever its borders.[64]

An arms embargo was declared with the intention that neither side would make gains from the truce. Neither side respected the truce; both found ways around the restrictions. Both the Israelis and the Arabs used this time to improve their positions, a direct violation of the terms of the ceasefire.

"The Arabs violated the truce by reinforcing their lines with fresh units (including six companies of Sudanese regulars,[64] Saudi battalion [65] and contingents from Yemen, Morocco [66]) and by preventing supplies from reaching isolated Israeli settlements; occasionally, they opened fire along the lines".[67] The Israeli Defense Forces violated the truce by acquiring weapons from Czechoslovakia, improving training of forces, and reorganising the army. Yitzhak Rabin, an IDF commander who became Israel's fifth prime minister, said, "[w]ithout the arms from Czechoslovakia... it is very doubtful whether we would have been able to conduct the war".[68] As well as violating the arms and personnel embargo, both sides sent fresh units to the front.[67] Israel's army increased its manpower from approximately 30,000 or 35,000 men to almost 65,000 during the truce and its arms supply to "more than twenty-five thousand rifles, five thousand machine guns, and more than fifty million bullets".[67]

As the truce began, a British officer stationed in Haifa said the four-week-long truce "would certainly be exploited by the Jews to continue military training and reorganization while the Arabs would waste [them] feuding over the future divisions of the spoils".[67] On 7 July, the day before the truce expired, Egyptian forces under General Muhammad Naguib renewed the war by attacking Negba.[69]

Second phase: 8–18 July 1948

Israeli forces launched a simultaneous offensive on all three fronts: Dani, Dekel, and Kedem. The fighting was dominated by large-scale Israeli offensives and a defensive Arab posture, and continued for ten days until the UN Security Council issued the Second Truce on 18 July.[67]

Israeli Operation Danny resulted in the exodus from Lydda and Ramle of 60,000 Palestinian residents. According to Benny Morris, in Ben-Gurion's view, Ramlah and Lydda constituted a special danger because their proximity might encourage cooperation between the Egyptian army, which had started its attack on Kibbutz Negbah, and the Arab Legion, which had taken the Lydda police station. Widespread looting took place during these operations, and about 100,000 Palestinians became refugees.[70] In Operation Dekel, Nazareth was captured on 16 July. In Operation Brosh, Israel tried and failed to drive the Syrian army out of northeastern Galilee. By the time the second truce took effect at 19:00 18 July, Israel had taken the lower Galilee from Haifa Bay to the Sea of Galilee.

18 July 1948 to 10 March 1949

At 19:00 on 18 July, the second truce of the conflict went into effect after intense diplomatic efforts by the UN. On 16 September, a new partition for Palestine was proposed, but was rejected by both sides.

Palmach Infantry go into action during the fight for Beersheba, 21 October

Palmach Infantry go into action during the fight for Beersheba, 21 October Israeli soldiers attack Sasa during Operation Hiram, October

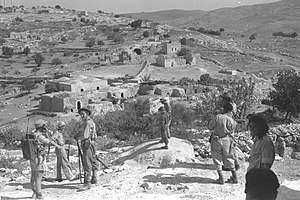

Israeli soldiers attack Sasa during Operation Hiram, October IDF forces near Beit Natif (near Hebron) after it was occupied, October

IDF forces near Beit Natif (near Hebron) after it was occupied, October Israeli bombardment of the Iraq Suwaydan fort, held by the Egyptian army, on 9 November

Israeli bombardment of the Iraq Suwaydan fort, held by the Egyptian army, on 9 November Palmach soldiers are instructed before Operation Yoav

Palmach soldiers are instructed before Operation Yoav Negev Brigade prior to Operation Horev

Negev Brigade prior to Operation Horev

During the truce, the Egyptians regularly blocked with fire the passage of supply convoys to the beleaguered northern Negev settlements, contrary to the truce terms. On 15 October, they attacked another supply convoy, and the already planned Operation Yoav was launched.[71] Its goal was to drive a wedge between the Egyptian forces along the coast and the Beersheba-Hebron-Jerusalem road, and to open the road to the encircled Negev settlements. Yoav was headed by Southern Front commander Yigal Allon. The operation was a success, shattering the Egyptian army ranks and forcing Egyptian forces to retreat from the northern Negev, Beersheba and Ashdod. Meanwhile, on 19 October, Operation Ha-Har commenced operations in the Jerusalem Corridor.

On 22 October, the third truce went into effect.[72]

Before dawn on 22 October, in defiance of the UN Security Council ceasefire order, ALA units stormed the IDF hilltop position of Sheikh Abd, overlooking Kibbutz Manara. The kibbutz was now besieged. Ben-Gurion initially rejected Moshe Carmel’s demand to launch a major counteroffensive. He was wary of antagonising the United Nations on the heels of its ceasefire order. During 24–25 October, ALA troops regularly sniped at Manara and traffic along the main road. In contacts with UN observers, Fawzi al-Qawuqji demanded that Israel evacuate neighbouring Kibbutz Yiftah and thin out its forces in Manara. The IDF demanded the ALA's withdrawal from the captured positions and, after a “no” from al-Qawuqji, informed the UN that it felt free to do as it pleased.[73] On 24 October, the IDF launched Operation Hiram and captured the entire upper Galilee, originally attributed to the Arab state by the Partition Plan. It drove the ALA back to Lebanon. At the end of the month, Israel had captured the whole Galilee and had advanced 5 miles (8.0 km) into Lebanon to the Litani River.

On 22 December, large IDF forces started Operation Horev. Its objective was to encircle the Egyptian Army in the Gaza Strip and force the Egyptians to end the war. The operation was a decisive Israeli victory, and Israeli raids into the Nitzana area and the Sinai Peninsula forced the Egyptian army into the Gaza Strip, where it was surrounded. Israeli forces withdrew from Sinai and Gaza under international pressure and after the British threatened to intervene against Israel. The Egyptian government announced on 6 January 1949 that it was willing to enter armistice negotiations. Allon persuaded Ben-Gurion to continue as planned, but Ben-Gurion told him: "Do you know the value of peace talks with Egypt? After all, that is our great dream!"[74] He was sure that Transjordan and the other Arab states would follow suit. On 7 January 1949, a truce was achieved.

On 5 March, Israel launched Operation Uvda; by 10 March, the Israelis reached Umm Rashrash (where Eilat was built later) and took it without a battle. The Negev Brigade and Golani Brigade took part in the operation. They raised a hand-made flag ("The Ink Flag") and claimed Umm Rashrash for Israel.

Aftermath

Armistice lines

In 1949, Israel signed separate armistices with Egypt on 24 February, Lebanon on 23 March, Transjordan on 3 April, and Syria on 20 July. The armistice lines saw Israel holding about 78% of mandate Palestine (as it stood after the independence of Transjordan in 1946), 22% more than the UN Partition Plan had allocated. These ceasefire lines were known afterwards as the "Green Line". The Gaza Strip and the West Bank were occupied by Egypt and Transjordan, respectively. The United Nations Truce Supervision Organization and Mixed Armistice Commissions were set up to monitor ceasefires, supervise the armistice agreements, to prevent isolated incidents from escalating, and assist other UN peacekeeping operations in the region.

Casualties

Israel lost 6,373 of its people, about 1% of its population in the war. About 4,000 were soldiers and the rest were civilians. The exact number of Arab losses is unknown but is estimated at between 4,000 for Egypt (2,000), Jordan and Syria (1,000 each)[10] and 15,000.[75]

Demographic consequences

During the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine and the 1948 Arab–Israeli War that followed, around 700,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled.[16] In 1951, the UN Conciliation Commission for Palestine estimated that the number of Palestinian refugees displaced from Israel was 711,000.[76] This number did not include displaced Palestinians inside Israeli-held territory. The list of villages depopulated during the Arab–Israeli conflict includes more than 400 Arab villages. It also includes about ten Jewish villages and neighbourhoods.

The causes of the 1948 Palestinian exodus are a controversial topic among historians.[77] The Palestinian refugee problem and the debate around the right of their return are also major issues of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Palestinians have staged annual demonstrations and protests on 15 May of each year.

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, around 10,000 Jews were forced to evacuate their homes in Palestine or Israel.[78] The war indirectly created a second, major refugee problem, the Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim lands. Partly because of the war between Jews and Arabs in Palestine, hundreds of thousands of Jews who lived in the Arab states were intimidated into flight, or were expelled from their native countries, most of them reaching Israel. The immediate reasons for the flight were the popular Arab hostility, including pogroms, triggered by the war in Palestine and anti-Jewish governmental measures.[79] In the three years following the war, about 700,000 Jews immigrated to Israel, where they were absorbed, fed and housed[80] mainly along the borders and in former Palestinian lands.[27] Beginning in 1948, and continuing until 1972, an estimated 800,000 to 1,000,000 Jews fled or were expelled.[81][82][83] From 1945 until the closure of 1952, more than 250,000 Jewish displaced persons lived in European refugee camps. About 136,000 of them immigrated to Israel.[22] More than 270,000 Jews immigrated from Eastern Europe,[23] mainly Romania and Poland (over 100,000 each). Overall 700,000 Jews settled in Israel,[84] doubling its Jewish population.[85][86]

Historiography

Since the war, Israeli and Arab historiographies have interpreted the events of 1948 differently. In Western historiography, the majority view was that the vastly outnumbered and ill-equipped Jews fended off the massed strength of the invading Arab armies; it was also widely believed that the Palestinian Arabs left their homes on their leaders' instructions.[87]

In 1980, with the opening of the Israeli and British archives, Israeli historians started giving new insights into the history of this period. In particular, the roles played by Abdullah I of Jordan and the British government, the goals of the different Arab nations, the balance of force, and the events related to the Palestinian exodus have been viewed with more nuance or given new interpretations.[87] These insights are the result of historical analysis of "the war as contingent on the flow of battle and voluntary/involuntary movements of threatened populations—rather than on any masterplan or evil intentions that would raise questions about Israel's legitimacy."[88] Some issues continue to be hotly debated among historians of the conflict.[89]

Palestinian and Arab historians have also provided context, but their work tends to be apologetic, rely on subjective sources, and assign blame for the Arab defeat. Palestinian historians since the 1960s who have used historical methodologies have not had the same impact on Arab society as Israeli New Historians did in Israeli society. This is due, in part, to fear that critical analysis of their role in the war might weaken the Palestinian position in the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Unlike Israel and Britain, Arab governments have not released relevant primary sources from their archives.[88]

In popular culture

A 2015 PBS documentary, A Wing and a Prayer, depicts the Al Schwimmer-led airborne smuggling missions to arm Israel.[90]

See also

Notes

- Israelis refer to the war as their War of Independence or War of Liberation, because the modern State of Israel originated in the Yishuv (the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine) declaring its independence from the British Mandate in 1948. Palestinians refer to this as al-Nakba ("the Catastrophe"), because of the land they lost,[12] the failure to create a Palestinian Arab State, and the 1948 Palestinian exodus.

Citations

- Anita Shapira, L'imaginaire d'Israël : histoire d'une culture politique (2005), Latroun : la mémoire de la bataille, Chap. III. 1 l'événement p. 91–96

- Benny Morris (2008), p.419.

- Palestine Post, "Israel's Bedouin Warriors", Gene Dison, August 12, 1948

- AFP (24 April 2013). "Bedouin army trackers scale Israel social ladder". Al Arabiya. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Benny Morris, 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War, Chapter 5.

- Moshe Yegar, "Pakistan and Israel," Jewish Political Studies Review 19:3–4 (Fall 2007)

- Pollack, 2004; Sadeh, 1997

- Sandler, Stanley (2002). Ground Warfare: An International Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 160.

- Rosemarie Esber, Under the Cover of War, Arabicus Books & Medica, 2009, p.28.

- Casualties in Arab-Israeli Wars

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, 4th ed. McFarland. p. 572. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Michael R. Fischbach, an American scholar of the archives of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, estimates that, in all, Palestinians lost some 6 to 8 million dunams (1.5 to 2 million acres) of land, not including communal land farmed by villages or state land. Philip Mattar, ‘Al-Nakba,’ in Philip Mattar Encyclopedia of the Palestinians, Infobase Publishing, 2005

- Reuven Firestone To Jews, the Jewish-Arab war of 1947–1948 is the War of Independence (milchemet ha'atzma'ut). To Arabs, and especially Palestinians, it is the nakba or calamity. I therefore refrain from assigning names to wars. I refer to the wars between the State of Israel and its Arab and Palestinian neighbors according to their dates: 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982.' Reuven Firestone, Holy War in Judaism: The Fall and Rise of a Controversial Idea, Oxford University Press, 2012 p.10, cf.p.296

- Neil Caplan, ‘Perhaps the most famous case of differences over the naming of events is the 1948 war (more accurately, the fighting from December 1947 through January 1949). For Israel it is their “War of Liberation” or “War of Independence” (in Hebrew, milhemet ha-atzama’ut) full of the joys and overtones of deliverance and redemption. For Palestinians, it is Al-Nakba, translated as “The Catastrophe” and including in its scope the destruction of their society and the expulsion and flight of some 700,000 refugees.’ The Israel-Palestine Conflict: Contested Histories, John Wiley & Sons, Sep 19, 2011 p.17.

- Neil Caplan Although some historians would cite 14 May 1948 as the start of the war known variously as the Israeli War of Independence, an-Nakba (the (Palestinian) Catastrophe), or the first Palestine war, it would be more accurate to consider that war as beginning on 30 November 1947'. Futile Diplomacy: The United Nations, the Great Powers, and Middle East Peacemaking 1948–1954, (vol.3) Frank Cass & Co, 1997 p.17

- — Benny Morris, 2004. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, pp. 602–604. Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6. "It is impossible to arrive at a definite persuasive estimate. My predilection would be to opt for the loose contemporary British formula, that of 'between 600,000 and 760,000' refugees; but,if pressed, 700,000 is probably a fair estimate";

— Memo US Department of State, 4 May 1949, FRUS, 1949, p. 973.: "One of the most important problems which must be cleared up before a lasting peace can be established in Palestine is the question of the more than 700,000 Arab refugees who during the Palestine conflict fled from their homes in what is now Israeli occupied territory and are at present living as refugees in Arab Palestine and the neighbouring Arab states.";

— Memorandum on the Palestine Refugee Problem, 4 May 1949, FRUS, 1949, p. 984.: "Approximately 700,000 refugees from the Palestine hostilities, now located principally in Arab Palestine, Transjordan, Lebanon and Syria, will require repatriation to Israel or resettlement in the Arab states." - Morris (2008), p.77

- Morris (2008), p.63–65

- Morris (2008), p.77–79

- Tal (2003), p.41

- Devorah Hakohen, Immigrants in Turmoil: Mass Immigration to Israel and Its Repercussions in the 1950s and after, Syracuse University Press 2003 p.267

- Displaced Persons retrieved on 29 October 2007 from the U.S. Holocaust Museum.

- Tom Segev, 1949. The First Israelis, Owl Books, 1986, p.96.

- Morris, 2001, chap. VI.

- "Jewish Refugees of the Israeli Palestinian Conflict". Mideast Web. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- Axelrod, Alan (2014). Idiot's Guides: The Middle East Conflict. Penguin Group. ISBN 9781615646401.

- Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, chap. VI.

- Morris (2008), p. 7

- Morris (2008), p. 2

- Morris (2008), p. 6–7

- Morris (2008), pp. 7–8

- Morris (2008), pp. 9–10

- Morris (2008), pp. 66–69

- "A/RES/181(II) of 29 November 1947". domino.un.org. 1947. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- Benny Morris (2008). 1948: a history of the first Arab-Israeli war. Yale University Press. p. 47. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

The Jews were to get 62 percent of Palestine (most of it desert), consisting of the Negev

- Pappe, 2006, p. 35

- Karsh, p.7

- El-Nawawy, 2002, p. 1-2

- Morris, 'Righteous Victims ...', 2001, p. 190

- Gold, 2007, p. 134

- UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION COMMISSION FOR PALESTINE A/AC.25/W/19 30 July 1949 Archived 2 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine,"The Arabs rejected the United Nations Partition Plan so that any comment of theirs did not specifically concern the status of the Arab section of Palestine under partition but rather rejected the scheme in its entirety."

- Benny Morris (2008). 1948: a history of the first Arab-Israeli war. Yale University Press. p. 67. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

p. 67, "The League’s Political Committee met in Sofar, Lebanon, on 16–19 September, and urged the Palestine Arabs to fight partition, which it called “aggression,” “without mercy"'; p. 70, '"On 24 November the head of the Egyptian delegation to the General Assembly, Muhammad Hussein Heykal, said that “the lives of 1,000,000 Jews in Moslem countries would be jeopardized by the establishment of a Jewish state."

- "Arab League Declaration on the Invasion of Palestine, 15 May 1948", Jewish Virtual Library. Archived December 19, 2010, at WebCite

- Resolution 181 (II). Future government of Palestine A/RES/181(II)(A+B) 29 November 1947 Archived June 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Special UN commission (16 April 1948), § II.5

- Yoav Gelber (2006), p.85

- Yoav Gelber (2006), pp.51-56

- Dominique Lapierre et Larry Collins (1971), chap.7, pp.131-153

- Benny Morris (2003), p. 163

- Henry Laurens (2005), p.83

- Dominique Lapierre et Larry Collins (1971), p.163

- Benny Morris (2003), p.67

- Benny Morris (2008). 1948: a history of the first Arab-Israeli war. Yale University Press. p. 116. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

At the time, Ben-Gurion and the HGS believed that they had initiated a one-shot affair, albeit with the implication of a change of tactics and strategy on the Jerusalem front. In fact, they had set in motion a strategic transformation of Haganah policy. Nahshon heralded a shift from the defensive to the offensive and marked the beginning of the implementation of tochnit dalet (Plan D)—without Ben-Gurion or the HGS ever taking an in principle decision to embark on its implementation.

- Dominique Lapierre et Larry Collins (1971), pp.369-381

- Benny Morris (2003), pp. 242-243

- Benny Morris (2003), p.242

- Henry Laurens (2005), pp.85-86

- Benny Morris (2003), pp.248-252

- Benny Morris (2003), pp.252-254

- Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Declaration of Establishment of State of Israel: 14 May 1948 Retrieved 9 April 2012 Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- The Origins and Evolution of the Palestine Problem, Part II, 1947–1977" Archived 2011-05-26 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations

- "The First Truce". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- Morris, Benny (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12696-9.

- Benny Morris (2008), p.269

- Benny Morris (2008), p.322

- Benny Morris (2008), p.205

- Morris, Benny. 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War.

- Ahron Bregman; Jihan El-Tahri (1999). The Fifty Years War: Israel and the Arabs. BBC Books.

- Alfred A. Knopf. A History of Israel from the Rise of Zionism to Our Time. New York. 1976. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-394-48564-5.

- Morris, 2004, p. 448.

- Benny Morris (2008), p.323.

- Shapira, Anita. Yigal Allon; Native Son; A Biography, Translated by Evelyn Abel, University of Pennsylvania Press ISBN 978-0-8122-4028-3 p 247

- Benny Morris (2008). 1948: a history of the first Arab-Israeli war. Yale University Press. p. 339. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

Al-Qawuqji supplied the justification for Operation Hiram, in which the IDF overran the north-central Galilee "pocket" and a strip of southern Lebanon... In truth, as with Yoav, Operation Hiram had been long in the planning... on 6 October, at the IDF General Staff meeting, Carmel had pressed for [Hiram] authorization, but the Cabinet held back. The Arabs were shortly to give him his chance. Before dawn on 22 October, in defiance of the UN Security Council cease-fire order, ALA units stormed the IDF hilltop position of Sheikh Abd, just north of, and overlooking, Kibbutz Manara... Manara was imperiled... Ben-Gurion initially rejected Carmel's demand to launch a major counteroffensive. He was chary of antagonizing the United Nations so close on the heels of its cease-fire order. ... The kibbutz was now besieged, and the main south-north road through the Panhandle to Metulla was also under threat. During the 24–25 October ALA troops regularly sniped at Manara and at traffic along the main road. In contacts with UN observers, al-Qawuqji demanded that Israel evacuate neighboring Kibbutz Yiftah... and thin out its forces in Manara. The IDF demanded the ALA's withdrawal from the captured positions and, after a "no" from al-Qawuqji, informed the United Nations that it felt free to do as it pleased. Sensing what was about to happen, the Lebanese army "ordered" al-Qawuqji to withdraw from Israeli territory—but to no avail. Al-Qawuqji's provocation at Sheikh Abd made little military sense... On 16 October, a week before the attack on Sheikh Abd, Carmel ... had pressed Ben-Gurion to be allowed "to begin in the Galilee." Ben-Gurion had refused, but on 24–25 October he gave the green light.

- Benny Morris (2008), p.369.

- Chris Cook, World Political Almanac, 3rd Ed. (Facts on File: 1995)

- United Nations General Assembly Session 5 General Progress Report and Supplementary Report of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, Covering the Period from 11 December 1949 to 23 October 1950 A/1367/REV.1(SUPP) page 24. 23 October 1950. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- L. Rogan, Eugene; Shlaim, Avi. "The War for Palestine. Rewriting the History of 1948". Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 2009-08-11. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- "Jewish Refugees of the Israeli Palestinian Conflict". Mideast Web. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- Benny Morris (1 October 2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. p. 412. ISBN 978-0-300-14524-3.

The war indirectly created a second, major refugee problem. Partly because of the clash of Jewish and Arab arms in Palestine, some five to six hundred thousand Jews who lived in the Arab world emigrated, were intimidated into flight, or were expelled from their native countries, most of them reaching Israel, with a minority resettling in France, Britain, and the other Western countries. The immediate propellants to flight were the popular Arab hostility, including pogroms, triggered by the war in Palestine and specific governmental measures, amounting to institutionalized discrimination against and oppression of the Jewish minority communities.

- David J Goldberg (28 Aug 2010). "A book review of: In Ishmael's House: A History of Jews in Muslim Lands by Martin Gilbert". The Guardian.

while it is pertinent to point out that 850,000 Jewish refugees from Arab lands have been fed, housed and absorbed by Israel since 1948 while 750,000 Palestinian refugees languish in camps, dependent on United Nations handouts

- Malka Hillel Shulewitz, The Forgotten Millions: The Modern Jewish Exodus from Arab Lands, Continuum 2001.

- Ada Aharoni "The Forced Migration of Jews from Arab Countries Archived 2012-02-13 at the Wayback Machine, Historical Society of Jews from Egypt website. Accessed April 4, 2013.

- Yehuda Zvi Blum (1987). For Zion's Sake. Associated University Presse. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8453-4809-3.

- Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, chap.VI.

- Population, by Religion and Population Group, Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, 2006, archived from the original on 30 September 2007, retrieved 7 August 2007

- Dvora Hacohen, Immigrants in Turmoil: Mass Immigration to Israel and its Repercussions in the 1950s and After, Syracuse University Press, 2003

- Avi Shlaim, "The Debate about 1948", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Aug., 1995), pp. 287–304.

- Sela, Avraham and Neil Caplan. "Epilogue: Reflections on Post-Oslo Israeli and Palestinian History and Memory of 1948." The War of 1948: Representations of Israeli and Palestinian Memories and Narratives, edited by Sela and Alon Kadish, Indiana University Press, 2016, pp. 203-221.

- Jeff Weintraub, "Benny Morris on fact, fiction, & propaganda about 1948", The Irish Times, 21 February 2008, Archived August 14, 2009, at WebCite

- "Israeli Air Force, particularly its scrappy beginnings, inspires 3 films". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

Further reading

- Abdel Jawad, Saleh (2006). "The Arab and Palestinian Narratives of the 1948 War". In Robert I. Rotberg (ed.). Israeli and Palestinian Narratives of Conflict: History's Double Helix. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21857-8.

- Caplan, Neil (19 September 2011). "War: Atzma'ut and Nakba". The Israel-Palestine Conflict: Contested Histories. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5786-8.

- Yoav Gelber, Palestine 1948, Sussex Academic Press, Brighton, 2006, ISBN 978-1-84519-075-0

- Efraim Karsh, The Arab-Israeli Conflict: The Palestine War 1948, Osprey publishing, 2002.

- Walid Khalidi (ed.), All that remains.ISBN 978-0-88728-224-9.

- Walid Khalidi, Selected Documents on the 1948 Palestine War, Journal of Palestine Studies, 27(3), 79, 1998.

- Benny Morris, 1948, Yale University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-300-12696-9

- Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oneworld Publications, 2006, ISBN 978-1-85168-555-4

- Eugene Rogan & Avi Shlaim, The War for Palestine — Rewriting the history of 1948, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- David Tal, War in Palestine, 1948. Strategy and Diplomacy, Routledge, 2004.