History of Morocco

History of human habitation in Morocco spans since Lower Paleolithic, with the earliest known being Jebel Irhoud. Much later Morocco was part of Iberomaurusian culture, including Taforalt. It dates from the establishment of Mauretania and other ancient Berber kingdoms, to the establishment of the Moroccan state by the Idrisid dynasty[1] followed by other Islamic dynasties, through to the colonial and independence periods.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Morocco |

|

|

|

Related topics

|

|

|

Archaeological evidence has shown that the area was inhabited by hominids at least 400,000 years ago.[2] The recorded history of Morocco begins with the Phoenician colonization of the Moroccan coast between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE,[3] although the area was inhabited by indigenous Berbers for some two thousand years before that. In the 5th century BCE, the city-state of Carthage extended its hegemony over the coastal areas.[4] They remained there until the late 3rd century BCE,[5] while the hinterland was ruled by indigenous monarchs.[4] Indigenous Berber monarchs ruled the territory from the 3rd century BCE until 40 CE, when it was annexed to the Roman Empire. In the mid-5th century AD, it was overrun by Vandals, before being recovered by the Byzantine Empire in the 6th century.

The region was conquered by the Muslims in the early 8th century AD, but broke away from the Umayyad Caliphate after the Berber Revolt of 740. Half a century later, the Moroccan state was established by the Idrisid dynasty.[6][7] Under the Almoravid and the Almohad dynasties, Morocco dominated the Maghreb and Muslim Spain. The Saadi dynasty ruled the country from 1549 to 1659, followed by the Alaouites from 1667 onwards, who have since been the ruling dynasty of Morocco.[8][9][10]

Prehistoric Morocco

Archaeological excavations have demonstrated the presence of people in Morocco that were ancestral to Homo sapiens, as well as the presence of early human species. The fossilized bones of a 400,000-year-old early human ancestor were discovered in Salé in 1971.[2] The bones of several very early Homo sapiens were excavated at Jebel Irhoud in 1991, these were dated using modern techniques in 2017 and found to be at least 300,000 years old, making them the oldest examples of Homo Sapiens discovered anywhere in the world.[11] In 2007, small perforated seashell beads were discovered in Taforalt that are 82,000 years old, making them the earliest known evidence of personal adornment found anywhere in the world.[12]

In Mesolithic times, between 20,000 and 5000 years ago, the geography of Morocco resembled a savanna more than the present arid landscape.[13] While little is known of settlements in Morocco during that period, excavations elsewhere in the Maghreb region have suggested an abundance of game and forests that would have been hospitable to Mesolithic hunters and gatherers, such as those of the Capsian culture.[14]

During the Neolithic period, which followed the Mesolithic, the savanna was occupied by hunters and herders. The culture of these Neolithic hunters and herders flourished until the region began to desiccate after 5000 BCE as a result of climatic changes. The coastal regions of present-day Morocco in the early Neolithic shared in the Cardium pottery culture that was common to the entire Mediterranean region. Archaeological excavations have suggested that the domestication of cattle and the cultivation of crops both occurred in the region during that period. In the Chalcolithic period, or the copper age, the Beaker culture reached the north coast of Morocco.

Early history

Carthage (c. 800 – c. 300 BCE)

The arrival of Phoenicians on the Moroccan coast heralded many centuries of rule by foreign powers in the north of Morocco.[15] Phoenician traders penetrated the western Mediterranean before the 8th century BCE, and soon after set up depots for salt and ore along the coast and up the rivers of the territory of present-day Morocco.[3] Major early settlements of the Phoenicians included those at Chellah, Lixus and Mogador.[16] Mogador is known to have been a Phoenician colony by the early 6th century BCE.[17]

By the 5th century BCE, the state of Carthage had extended its hegemony across much of North Africa. Carthage developed commercial relations with the Berber tribes of the interior, and paid them an annual tribute to ensure their cooperation in the exploitation of raw materials[18]

Mauretania (c. 300 BCE – c. 430 AD)

Mauretania was an independent tribal Berber kingdom on the Mediterranean coast of north Africa, corresponding to northern modern-day Morocco from about the 3rd century BCE.[19] The earliest known king of Mauretania was Bocchus I, who ruled from 110 BCE to 81 BCE . Some of its earliest recorded history relates to Phoenician and Carthaginian settlements such as Lixus and Chellah.[19] The Berber kings ruled inland territories overshadowing the coastal outposts of Carthage and Rome, often as satellites, allowing Roman rule to exist. It became a client of the Roman empire in 33 BCE, then a full province after Emperor Caligula had the last king, Ptolemy of Mauretania, executed (AD 40).

Rome controlled the vast, ill-defined territory through alliances with the tribes rather than through military occupation, expanding its authority only to those areas, that were economically useful or that could be defended without additional manpower. Hence, Roman administration never extended outside the restricted area of the northern coastal plain and valleys. This strategic region formed part of the Roman Empire, governed as Mauretania Tingitana, with the city of Volubilis as its capital.

During the time of the Roman emperor Augustus, Mauretania was a vassal state, and its rulers, such as Juba II, controlled all the areas south of Volubilis. But the effective control of Roman legionaries reached as far as the area of Sala Colonia (the castra "Exploratio Ad Mercurios" south of Sala is the southernmost discovered up to now). Some historians believe the Roman frontier reached present-day Casablanca, known then as Anfa, which had been settled by the Romans as a port.

During the reign of Juba II, the Augustus founded three colonies, with Roman citizens, in Mauretania close to the Atlantic coast: Iulia Constantia Zilil, Iulia Valentia Banasa, and Iulia Campestris Babba. Augustus would eventually found twelve colonies in the region.[20] During that period, the area controlled by Rome experienced significant economic development, aided by the construction of Roman roads. The area was initially not completely under the control of Rome, and only in the mid-2nd century was a limes built south of Sala extending to Volubilis. Around 278 AD the Romans moved their regional capital to Tangier and Volubilis started to lose importance.

Christianity was introduced to the region in the 2nd century AD, and gained converts in the towns and among slaves as well as among Berber farmers. By the end of the 4th century, the Romanized areas had been Christianized, and inroads had been made among the Berber tribes, who sometimes converted en masse. Schismatic and heretical movements also developed, usually as forms of political protest. The area had a substantial Jewish population as well.

Early Islamic Morocco (c. 700 – c. 1060)

Muslim conquest (c. 700)

The Muslim conquest of the Maghreb, that started in the middle of the 7th century AD, was achieved in the early 8th century. It brought both the Arabic language and Islam to the area. Although part of the larger Islamic Empire, Morocco was initially organized as a subsidiary province of Ifriqiya, with the local governors appointed by the Muslim governor in Kairouan.[22]

The indigenous Berber tribes adopted Islam, but retained their customary laws. They also paid taxes and tribute to the new Muslim administration.[23]

Berber Revolt (740–743)

In 740 AD, spurred on by puritanical Kharijite agitators, the native Berber population revolted against the ruling Ummayad Caliphate. The rebellion began among the Berber tribes of western Morocco, and spread quickly across the region. Although the insurrection petered out in 742 AD before it reached the gates of Kairouan, neither the Umayyad rulers in Damascus nor their Abbasid successors managed to re-impose their rule on the areas west of Ifriqiya. Morocco passed out of Umayyad and Abbasid control, and fragmented into a collection of small, independent Berber states such as Berghwata, Sijilmassa and Nekor, in addition to Tlemcen and Tahert in what is now western Algeria.[21] The Berbers went on to shape their own version of Islam. Some, like the Banu Ifran, retained their connection with radical puritan Islamic sects, while others, like the Berghwata, constructed a new syncretic faith.[24][25]

Barghawata (744–1058)

The Barghawatas were a confederation of Berber groups inhabiting the Atlantic coast of Morocco, who belonged to the Masmuda Berber tribal division.[21] After allying with the Sufri Kharijite rebellion in Morocco against the Umayyads, they established an independent state (CE 744 – 1058) in the area of Tamesna on the Atlantic coast between Safi and Salé under the leadership of Tarif al-Matghari.

Sijilmassa (700s – 1300s)

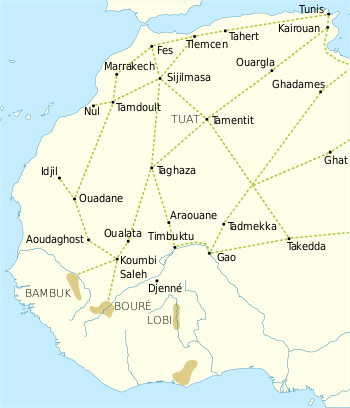

Sijilmasa was a medieval Moroccan city and trade entrepôt at the northern edge of the Sahara desert. The ruins of the town lie for 8 kilometres (5 mi) along the River Ziz in the Tafilalt oasis near the town of Rissani. The town's history was marked by several successive invasions by Berber dynasties. Up until the 14th century, as the northern terminus for the western trans-Sahara trade route, it was one of the most important trade centres in the Maghreb during the Middle Ages.[26]

Kingdom of Nekor (710–1019)

The Kingdom of Nekor was an emirate centered in the Rif area of Morocco. Its capital was initially located at Temsaman, and then moved to Nekor. The polity was founded in 710 AD by Salih I ibn Mansur through a Caliphate grant. Under his guidance, the local Berber tribes adopted Islam, but later deposed him in favor of one az-Zaydi from the Nafza tribe. They subsequently changed their mind and reappointed Ibn Mansur. His dynasty, the Banū Sālih, thereafter ruled the region until 1019.

In 859, the kingdom became subject to a 62 ship-strong group of Vikings, who defeated a Moorish force in Nekor that had attempted to interfere with their plunderings in the area. After staying for eight days in Morocco, the Vikings went back to Spain and continued up the east coast.[27]

Idrisid dynasty (789–974)

The Idrisid dynasty was a Muslim polity centered in Morocco,[28] which ruled from 788 to 974. Named after the founder Idriss I, the great grandchild of Hasan ibn Ali, the Idrisids are believed by some historians to be the founders of the first Moroccan state.[29]

Fatimid, Umayyad and Zenata polities (c. 900 – c. 1060)

This equilibrium was upset in the early 900s, when the Fatimid dynasty arrived in the Maghreb. Not long after seizing power in Ifriqiya, the Fatimids invaded Morocco, conquering both Fez and Sijilmassa. Morocco was fragmented in the aftermath, with Fatimid governors, Idrisid loyalists, new puritan groups and interventionists from Umayyad al-Andalus all fighting over the region. Opportunistic local governors sold and re-sold their support to the highest bidder. In 965, the Fatimid caliph al-Muizz invaded Morocco one last time and succeeded in establishing some order. Soon after, however, the Fatimids shifted their empire eastward to Egypt, with a new capital in Cairo.

The Fatimids had assigned the Zirids, a Zenaga Berber clan centered in Ifriqiya, to watch their western dominions. The Zirids, however, were unable to prevent Morocco from spinning out of their control and crumbling into the hands of a collection of local Zenata Berber chieftains, most of them clients of the Caliph of Cordoba, such as the Maghrawa in the region of Fez and itinerant rivals, the Banu Ifran to the east.

Berber dynasties (c. 1060 – 1549)

.jpg)

After 1060 a few Berber dynasties rose to power south of the Atlas Mountains and expanded their rule northward, replacing local rulers. The 11th and 12th centuries witnessed the founding of several significant Berber dynasties led by religious reformers, each dynasty based on a tribal confederation that dominated the Maghreb and Al-Andalus for more than 200 years. These were the Berber dynasties of the Almoravids, Almohads, Marinids and Wattasids.

Almoravid dynasty (c. 1060 – 1147)

The Almoravid dynasty (c.1060–1147) originated among the Lamtuna nomadic Berber tribe belonging to the Sanhaja. They succeeded in unifying Morocco after it had been divided among several Zenata principalities in the late 10th century, and annexed the Emirate of Sijilmasa and the Barghawata (Tamesna) into their realm.

Under Yusuf ibn Tashfin, the Almoravids were invited by the Muslim taifa princes of Al-Andalus to defend their territories from the Christian kingdoms. Their involvement was crucial in preventing the fall of Al-Andalus. After having succeeded in repelling Christian forces in 1086, Yusuf returned to Iberia in 1090 and annexed most of the major taifas.[31]

Almoravid power began to decline in the first half of the 12th century, as the dynasty was weakened after its defeat at the battle of Ourique and because of the agitation of the Almohads. The conquest of the city of Marrakech by the Almohads in 1147 marked the fall of the dynasty. However, fragments of the Almoravids (the Banu Ghaniya) continued to struggle in the Balearic Islands and in Tunisia.

Almohad dynasty (1147–1248)

The Almohad Caliphate was a Moroccan,[32][33] Berber Muslim movement founded in the 12th century.[34]

The Almohad movement was started by Ibn Tumart among the Masmuda tribes of southern Morocco. The Almohads first established a Berber state in Tinmel in the Atlas Mountains in roughly 1120.[34] They succeeded in overthrowing the ruling Almoravids in governing Morocco by 1147, when Abd al-Mu'min al-Gumi (r. 1130–1163) conquered Marrakech and declared himself Caliph. They then extended their power over all of the Maghreb by 1159. Al-Andalus followed the fate of the Maghreb and all Islamic Iberia was under Almohad rule by 1172.[35]

Marinid dynasty (1248–1465)

The Marinid dynasty was a Sunni Muslim[36] dynasty of Zenata Berber descent that ruled Morocco from the 13th to the 15th century.[37][38]

The Marinids overthrew the Almohad dynasty controlling Morocco in 1244,[39] and briefly controlled all the Maghreb in the mid-14th century. They supported the Kingdom of Granada in Al-Andalus in the 13th and 14th centuries; an attempt to gain a direct foothold on the European side of the Strait of Gibraltar was however defeated at the Battle of Río Salado in 1340 and finished after the Castilian conquest of Algeciras from the Marinids in 1344.[40]

Wattasid dynasty (1471–1549)

The Wattasid dynasty were a ruling dynasty of Morocco. Like the Marinids, they were of Zenata Berber descent.[41] The two families were related, and the Marinids recruited many viziers from the Wattasids.[41] The Wattasid dynasty was also in power during the Expulsion of Jews from Spain and Expulsion of the Jews from Portugal and saw many of those Jews seek refugee in Morroco.

Saadi dynasty (1549–1659)

Beginning in 1549, the region was ruled by successive Arab dynasties known as the Sharifian dynasties, who claimed descent from the prophet Muhammad. The first of these polities was the Saadi dynasty, which ruled Morocco from 1549 to 1659. From 1509 to 1549, the Saadi rulers had control of only the southern areas. While still recognizing the Wattasids as Sultans until 1528, Saadians' growing power led the Wattasids to attack them and, after an indecisive battle, to recognize their rule over southern Morocco through the Treaty of Tadla.[42]

In 1659, Mohammed al-Hajj ibn Abu Bakr al-Dila'i, the head of the zaouia of Dila,[43] was proclaimed sultan of Morocco after the fall of the Saadi dynasty.[44]

Alaouite dynasty (since 1666)

The Alaouite dynasty is the current Moroccan royal family. The name Alaouite comes from the ‘Alī of ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib, whose descendant Sharif ibn Ali became Prince of Tafilalt in 1631. His son Mulay Al-Rashid (1664–1672) was able to unite and pacify the country. The Alaouite family claim descent from Muhammad through his daughter Fāṭimah az-Zahrah and her husband ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib.

The kingdom was consolidated by Ismail Ibn Sharif (1672–1727), who began to create a unified state in the face of opposition from local tribes . Since the Alaouites, in contrast to previous dynasties, did not have the support of a single Berber or Bedouin tribe, Isma'īl controlled Morocco through an army of slaves. With these soldiers he drove the English from Tangiers (1684) and the Spanish from Larache in 1689. The unity of Morocco did not survive his death — in the ensuing power struggles the tribes became a political and military force once again, and it was only with Muhammad III (1757–1790) that the kingdom was unified again. The idea of centralization was abandoned and the tribes allowed to preserve their autonomy. On 20 December 1777,[45] Morocco became one of the first states to recognize the sovereignty of a newly independent United States.[46]

During the reigns of Muhammad IV (1859–1873) and Hassan I (1873–1894), the Alaouites tried to foster trade links, especially with European countries and the United States. The army and administration were also modernized to consolidate control over the Berber and Bedouin tribes. In 1859, Morocco went to war with Spain. The independence of Morocco was guaranteed at the Conference of Madrid in 1880,[47] with France also gaining significant influence over Morocco. Germany attempted to counter the growing French influence, leading to the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905–1906, and the Second Moroccan Crisis of 1911. Morocco became a French Protectorate through the Treaty of Fez in 1912.

European influence (c. 1830 – 1956)

.jpg)

The successful Portuguese efforts to control the Atlantic coast in the 15th century did not affect the interior of Morocco. After the Napoleonic Wars, North Africa became increasingly ungovernable from Istanbul by the Ottoman Empire. As a result, it became the resort of pirates under local beys. The Maghreb also had far greater known wealth than the rest of Africa, and its location near the entrance to the Mediterranean gave it strategic importance. France showed a strong interest in Morocco as early as 1830. The Alaouite dynasty succeeded in maintaining the independence of Morocco in the 18th and 19th centuries, while other states in the region succumbed to Ottoman, French, or British domination.

In 1844, after the French conquered Algeria, the Franco-Moroccan War took place, with the bombardment of Tangiers, the Battle of Isly, and the bombardment of Mogador.

Weakened by the war, Sultan Abd al-Rahman's Makhzen signed a deal negotiated with the British diplomat John Hay Drummond Hay in 1856 to make Great Britain Morocco's 'protector,' and to lower customs tariffs to 10%.[48] This effectively opened the country to foreign trade and broke the Makhzen's monopoly on customs revenue—a major source of income.[49]

The Hispano-Moroccan War took place 1859–60, and the Treaty of Wad Ras forced Morocco to take a massive British loan larger than its national reserves to pay off its war debt to Spain.[49]

In the mid 19th century, Moroccan Jews started migrating from the interior to coastal cities such as Essaouira, Mazagan, Asfi, and later Casablanca for economic opportunity, participating in trade with Europeans and the development of those cities.[50] The Alliance Israélite Universelle opened its first school in Tetuan in 1862.[51]

In the latter part of the 19th century Morocco's instability resulted in European countries intervening to protect investments and to demand economic concessions. Sultan Hassan I called for the Madrid Conference of 1880 in response to France and Spain's abuse of the protégé system, but the result was an increased European presence in Morocco—in the form of advisors, doctors, businessmen, adventurers, and even missionaries.[52]

More than half of the Makhzen's expenditures went abroad to pay war indemnities and buy weapons, military equipment, and manufactured goods.[52] From 1902 to 1909, Morocco's trade deficit increased 14 million francs annually, and the Moroccan rial depreciated 25% from 1896 to 1906.[52] In June 1904, after a failed attempt to impose a flat tax, France bailed out the already indebted Makhzen with 62.5 million franks, guaranteed by a portion of customs revenue.[52]

In the 1890s, the French administration and military in Algiers called for the annexation of the Touat, the Gourara and the Tidikelt,[53] a complex that had been part of the Moroccan Empire for many centuries prior to the arrival of the French in Algeria.[54] The first years of the 20th century saw major diplomatic efforts by European powers, especially France, to further its interests in the region.[55]

Morocco nominally was ruled by its sultan, the young Abd al-Aziz, through his regent, Ba Ahmed. By 1900, Morocco was the scene of multiple local wars started by pretenders to the sultanate, by bankruptcy of the treasury, and by multiple tribal revolts. The French Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé saw the opportunity to stabilize the situation and expand the French overseas empire.

General Hubert Lyautey wanted a more aggressive military policy using his French army based in Algeria. France decided to use both diplomacy and military force. With British approval, it would control the Sultan, ruling in his name and extending French control. British approval was received in the Entente Cordiale of 1904. The Germans, who had no established presence in the region, strongly protested. The Kaiser's dramatic intervention in Morocco in March 1905 in support of Moroccan independence became a turning point on the road to the First World War. The international Algeciras Conference of 1906 formalized France's "special position" and entrusted policing of Morocco jointly to France and Spain. Germany was outmaneuvered diplomatically, and France took full control of Morocco.[56][57]

Morocco experienced a famine from 1903 to 1907, as well as insurrections led by El-Rogui (Bou Hmara) and Mulai Ahmed er Raisuni.[52] Abd al-Hafid wrested the throne from his brother Abd al-Aziz in the Hafidiya (1907-1908) coup d'état.[58]

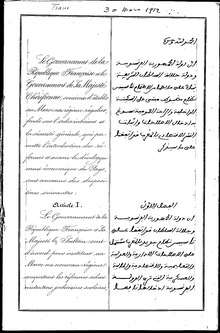

French and Spanish protectorate (1912–1956)

In 1907, the French took the murder of Émile Mauchamp in Marrakesh as a pretext to invade Oujda in the east, as they took an uprising against their appropriation of customs revenue in Casablanca as an opportunity to bombard and invade that city in the west.[59] The Agadir Crisis increased tensions among the powerful European countries, and resulted in the Treaty of Fez (signed on 30 March 1912), which made Morocco a protectorate of France. A second treaty signed by the French and Spanish heads of state, Spain was granted a Zone of influence in northern and southern Morocco on 27 November 1912. The northern part became the Spanish protectorate in Morocco, while the southern part was ruled from El Aaiun as a buffer zone between the Spanish Colony of Saguia El Hamra and Morocco. The treaty of Fez triggered the 1912 Fez riots. By the Tangier Protocol signed in December 1923, Tangier received special status and became an international zone.[60]

.jpg) The assassination of Émile Mauchamp March 1907, which precipitated the French invasion of Oujda and the conquest of Morocco.

The assassination of Émile Mauchamp March 1907, which precipitated the French invasion of Oujda and the conquest of Morocco. Uprisings in Casablanca in July 1907 over the application terms of the Treaty of Algeciras led to the Bombardment of Casablanca.

Uprisings in Casablanca in July 1907 over the application terms of the Treaty of Algeciras led to the Bombardment of Casablanca. Destruction of Casablanca caused by the 1907 French bombardment.

Destruction of Casablanca caused by the 1907 French bombardment. French artillery in Rabat in 1911. The dispatch of French forces to protect the sultan from a rebellion instigated the Agadir Crisis.

French artillery in Rabat in 1911. The dispatch of French forces to protect the sultan from a rebellion instigated the Agadir Crisis. Destruction after the Intifada of Fes was quelled by French artillery fire.[61]

Destruction after the Intifada of Fes was quelled by French artillery fire.[61]

The treaties nominally assured Morocco of its legal status as a sovereign state, with the sultan as its figurehead.[62][63] In practice, the sultan had no real power and the country was ruled by the colonial administration. French civil servants allied themselves with the French settlers and with their supporters in France to prevent any moves in the direction of Moroccan autonomy. As "pacification" proceeded, with the Zaian War and the War of the Rif, the French government focused on the exploitation of Morocco's mineral wealth, and particularly its phosphates; the creation of a modern transportation system with trains and buses; and the development of a modern agricultural sector geared to the French market. Tens of thousands of colons, or colonists, entered Morocco and acquired large tracts of the rich agricultural land.[64]

Morocco was home to half a million Europeans,[65] most of whom settled in Casablanca, where they formed almost half the population.[66] Since the kingdom's independence in 1956, and particularly after Hassan II's 1973 Moroccanization policies, the European element has largely departed.[64]

Opposition to European control

The separatist Republic of the Rif was declared on 18 September 1921, by the people of the Rif. It was dissolved by Spanish and French forces on 27 May 1926.

In December 1934, a small group of nationalists, members of the newly formed Comité d'Action Marocaine, or Moroccan Action Committee (CAM), proposed a Plan of Reforms that called for a return to indirect rule as envisaged by the Treaty of Fez, admission of Moroccans to government positions, and establishment of representative councils. CAM used petitions, newspaper editorials, and personal appeals to French officials to further its cause, but these proved inadequate, and the tensions created in the CAM by the failure of the plan caused it to split. The CAM was reconstituted as a nationalist political party to gain mass support for more radical demands, but the French suppressed the party in 1937[67].

Nationalist political parties, which subsequently arose under the French protectorate, based their arguments for Moroccan independence on declarations such as the Atlantic Charter, a joint United States-British statement that set forth, among other things, the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they live.[68] The French regime also faced the opposition of the tribes — when the Berber were required to come under the jurisdiction of French courts in 1930, it increased support for the independence movement[69].

Many Moroccan Goumiers, or indigenous soldiers in the French army, assisted the Allies in both World War I and World War II.[70] During World War II, the badly divided nationalist movement became more cohesive. However, the nationalists belief that an Allied victory would pave the way for independence was disappointed. In January 1944, the Istiqlal (Independence) Party, which subsequently provided most of the leadership for the nationalist movement, released a manifesto demanding full independence, national reunification, and a democratic constitution. The Sultan Muhammad V (1927–1961) had approved the manifesto before its submission to the French resident general, who answered that no basic change in the protectorate status was being considered. The general sympathy of the sultan for the nationalists became evident by the end of the war, although he still hoped to see complete independence achieved gradually. On 10 April 1947, Sultan Muhammad V delivered a momentous speech in Tangier appealing for the independence and territorial unity of Morocco, having traveled from French Morocco and through Spanish Morocco to reach the Tangier International Zone.[71] The résidence, supported by French economic interests and vigorously backed by most of the colons, adamantly refused to consider even reforms short of independence.

In December 1952, a riot broke out in Casablanca over the assassination of the Tunisian labor leader Farhat Hached; this event marked a watershed in relations between Moroccan political parties and French authorities. In the aftermath of the rioting, the residency outlawed the new Moroccan Communist Party and the Istiqlal Party.[72]

France's exile of the highly respected Sultan Mohammed V to Madagascar on Eid al-Adha of 1953, and his replacement by the unpopular Mohammed Ben Aarafa, sparked active opposition to the French protectorate both from nationalists and those who saw the sultan as a religious leader. In retribution, Muhammad Zarqtuni bombed Casablanca's Marché Central in the European ville nouvelle on Christmas of that year.[73] Two years later, faced with a united Moroccan demand for the sultan's return and rising violence in Morocco, as well as a deteriorating situation in Algeria, the French government brought Mohammed V back to Morocco, and the following year began the negotiations that led to Moroccan independence.

Independent Morocco (since 1956)

In late 1955, in the middle of what came to be known as the Revolution of the King and the People,[74] Sultan Mohammed V successfully negotiated the gradual restoration of Moroccan independence within a framework of French-Moroccan interdependence. The sultan agreed to institute reforms that would transform Morocco into a constitutional monarchy with a democratic form of government. In February 1956, Morocco acquired limited home rule. Further negotiations for full independence culminated in the French-Moroccan Agreement signed in Paris on 2 March 1956.[72]

On 7 April 1956, France officially relinquished its protectorate in Morocco. The internationalized city of Tangier was reintegrated with the signing of the Tangier Protocol on 29 October 1956. The abolition of the Spanish protectorate and the recognition of Moroccan independence by Spain were negotiated separately and made final in the Joint Declaration of April 1956.[72] Through this agreement with Spain in 1956 and another in 1958, Moroccan control over certain Spanish-ruled areas was restored. Attempts to claim other Spanish possessions through military action were less successful.

In the months that followed independence, Mohammed V proceeded to build a modern governmental structure under a constitutional monarchy in which the sultan would exercise an active political role. He acted cautiously, intent on preventing the Istiqlal from consolidating its control and establishing a one-party state. He assumed the monarchy in 1957.[75]

Reign of Hassan II (1961–1999)

Mohammed V's son Hassan II became King of Morocco on 3 March 1961. His rule saw significant political unrest, and the ruthless government response earned the period the name "the years of lead". Hassan took personal control of the government as prime minister, and named a new cabinet. Aided by an advisory council, he drew up a new constitution, which was approved overwhelmingly in a December 1962 referendum. Under its provisions, the king remained the central figure in the executive branch of the government, but legislative power was vested in a bicameral parliament, and an independent judiciary was guaranteed.

In May 1963, legislative elections took place for the first time, and the royalist coalition secured a small plurality of seats. However, following a period of political upheaval in June 1965, Hassan II assumed full legislative and executive powers under a "state of exception," which remained in effect until 1970. Subsequently, a reform constitution was approved, restoring limited parliamentary government, and new elections were held. However, dissent remained, revolving around complaints of widespread corruption and malfeasance in government. In July 1971 and again in August 1972, the regime was challenged by two attempted military coups.[76]

After neighbouring Algeria's 1962 independence from France, border skirmishes in the Tindouf area of south-western Algeria escalated in 1963 into what is known as the Sand War. The conflict ended after Organisation of African Unity mediation, with no territorial changes.[77]

On 3 March 1973, Hassan II announced the policy of Moroccanization, in which state-held assets, agricultural lands, and businesses that were more than 50 percent foreign-owned—and especially French-owned—were transferred to political loyalists and high-ranking military officers.[78][79] The Moroccanization of the economy affected thousands of businesses and the proportion of industrial businesses in Morocco that were Moroccan-owned immediately increased from 18% to 55%.[78] 2/3 of the wealth of the Moroccanized economy was concentrated in 36 Moroccan families.[78]

The patriotism engendered by Morocco's participation in the Middle East conflict and by the events in Western Sahara contributed to Hassan's popularity. The king had dispatched Moroccan troops to the Sinai front after the outbreak of the Arab-Israeli War in October 1973.[80] Although they arrived too late to engage in hostilities, the action won Morocco goodwill among other Arab states. Soon after, the attention of the government turned to the acquisition of Western Sahara from Spain, an issue on which all major domestic parties agreed.[72]

Western Sahara conflict (1974–1991)

The Spanish enclave of Ifni in the south became part of the new state of Morocco in 1969, but other Spanish possessions in the north, including Ceuta, Melilla and Plaza de soberanía, remained under Spanish control, with Morocco viewing them as occupied territory.

In August 1974, Spain formally acknowledged the 1966 United Nations (UN) resolution calling for a referendum on the future status of the Western Sahara, and requested that a plebiscite be conducted under UN supervision. A UN visiting mission reported in October 1975 that an overwhelming majority of the Saharan people desired independence. Morocco protested the proposed referendum and took its case to the International Court of Justice at The Hague, which ruled that despite historical "ties of allegiance" between Morocco and the tribes of Western Sahara, there was no legal justification for departing from the UN position on self-determination. Spain, meanwhile, had declared that even in the absence of a referendum, it intended to surrender political control of Western Sahara, and Spain, Morocco, and Mauritania convened a tripartite conference to resolve the territory's future. Spain also announced that it was opening independence talks with the Algerian-backed Saharan independence movement known as the Polisario Front.[72]

In early 1976, Spain ceded the administration of the Western Sahara to Morocco and Mauritania. Morocco assumed control over the northern two-thirds of the territory, and conceded the remaining portion in the south to Mauritania. An assembly of Saharan tribal leaders duly acknowledged Moroccan sovereignty. However, buoyed by the increasing defection of tribal chiefs to its cause, the Polisario drew up a constitution, and announced the formation of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), and itself formed government-in-exile.[72]

The Moroccan government eventually sent a large portion of its combat forces into Western Sahara to confront the Polisario's forces, which were relatively small but well-equipped, highly mobile, and resourceful. The Polisario used Algerian bases for quick strikes against targets deep inside Morocco and Mauritania, as well as for operations in Western Sahara. In August 1979, after suffering military losses, Mauritania renounced its claim to Western Sahara and signed a peace treaty with the Polisario. Morocco then annexed the entire territory and, in 1985 built a 2,500-kilometer sand berm around three-quarters of Western Sahara.[72]

In 1988, Morocco and the Polisario Front agreed on a United Nations (UN) peace plan, and a cease-fire and settlement plan went into effect in 1991. Even though the UN Security Council created a peacekeeping force to implement a referendum on self-determination for Western Sahara, it has yet to be held, periodic negotiations have failed, and the status of the territory remains unresolved.[72]

The war against the Polisario guerrillas put severe strains on the economy, and Morocco found itself increasingly isolated diplomatically. Gradual political reforms in the 1990s culminated in the constitutional reform of 1996, which created a new bicameral legislature with expanded, although still limited, powers. Elections for the Chamber of Representatives were held in 1997, reportedly marred by irregularities.[72]

Reign of Mohammed VI (since 1999)

With the death of King Hassan II of Morocco in 1999, the more liberal Crown Prince Sidi Mohammed took the throne, assuming the title Mohammed VI. He enacted successive reforms to modernize Morocco, and human-rights record of the country improved markedly.[81] One of the new king's first acts was to free approximately 8,000 political prisoners and reduce the sentences of another 30,000. He also established a commission to compensate families of missing political activists and others subjected to arbitrary detention.[72]

In September 2002, new legislative elections were held, and the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP) won a plurality. International observers regarded the elections as free and fair, noting the absence of the irregularities that had plagued the 1997 elections. In May 2003, in honor of the birth of a son, the king ordered the release of 9,000 prisoners and the reduction of 38,000 sentences. Also in 2003, Berber-language instruction was introduced in primary schools, prior to introducing it at all educational levels.[72]

In March 2000, women's groups organized demonstrations in Rabat proposing reforms to the legal status of women in the country. 200,000 to 300,000 women attended, calling for a ban on polygamy, and the introduction of civil divorce law.[82] Although a counter-demonstration attracted 200,000 to 400,000 participants, the movement was influential on King Mohammed, and he enacted a new Mudawana, or family law, in early 2004, meeting some of the demands of women's rights activists.[83]

In July 2002, a crisis broke out with Spain over a small, uninhabited island lying just less than 200 meters from the Moroccan coast, named Toura or Leila by Moroccans and Perejil by Spain. After mediation by the United States, both Morocco and Spain agreed to return to the status quo, under which the island remains deserted.[84][85]

Internationally, Morocco has maintained strong ties to the West. It was one of the first Arab and Islamic states to denounce the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States.[86]

In May 2003, Islamist suicide bombers simultaneously struck a series of sites in Casablanca, killing 45 and injuring more than 100 others. The Moroccan government responded with a crackdown against Islamist extremists, ultimately arresting several thousand, prosecuting 1,200, and sentencing about 900. Additional arrests followed in June 2004. That same month, the United States designated Morocco a major non-North Atlantic Treaty Organization ally, stating that it was in recognition of its efforts to thwart international terrorism. On 1 January 2006, a comprehensive bilateral free trade agreement between the United States and Morocco took effect.[72] The agreement had been signed in 2004 along with a similar agreement with the European Union, Morocco's main trade partner.

See also

- History of North Africa

- Imperial cities of Morocco

- List of Kings of Morocco

- Politics of Morocco

- Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic

- History of cities in Morocco:

- Timeline of Morocco

Notes

- "Moroccan dynasticshurfa'‐hood in two historical contexts: Idrisid cult and 'Alawid power". The Journal of North African Studies. 6 (2): 81–94. 2001. doi:10.1080/13629380108718436.

- Hublin, Jean Jacques (2010). "Northwestern African middle Pleistocene hominids and their bearing on the emergence of Homo Sapiens" (PDF). In Barham, Lawrence; Robson-Brown, Kate (eds.). Human Roots: Africa and Asia in the middle Pleistocene. Bristol, England: Western Academic and Specialist Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Pennell 2003, p.5

- Pennell 2003, pp.7–9

- Pennell 2003, pp.9–11

- "tradition (...) reaches back to the origins of the modern Moroccan state in the ninth century Idrisid dynasty which founded the venerable city of. Fes", G Joffe, Morocco: Monarchy, legitimacy and succession, in : Third World Quarterly, 1988

- "The Idrisids, the founder dynasty of Fas and, ideally at least, of the modern Moroccan state (...)", Moroccan dynastic shurfa’‐hood in two historical contexts: idrisid cult and ‘Alawid power in : The Journal of North African Studies Volume 6, Issue 2, 2001

- "The CBS News Almanac", Hammond Almanac Inc., 1976, p.783: "The Alaouite dynasty (Filali) has ruled Morocco since the 17th century"

- Hans Groth & Alfonso Sousa-Poza, "Population Dynamics in Muslim Countries: Assembling the Jigsaw", Springer, 2012 (ISBN 9783642278815). p.229: "The Alaouite dynasty has ruled Morocco since the days of Mulai ar-Rashid (1664–1672)"

- Joseph L. Derdzinski, "Internal Security Services in Liberalizing States: Transitions, Turmoil, and (In)Security", Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2013 (ISBN 9781409499015). p.47: "Hassan in 1961, after the death of his father Mohammed V, continued the succession of Alaouite rule in Morocco since the seventeenth century"

- Ghosh, Pallab (7 June 2017). "'First of our kind' found in Morocco". BBC News.

- "World's Oldest Manufactured Beads Are Older Than Previously Thought". Sciencedaily.com. 7 May 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- 1984 D. Lubell. Paleoenvironments and Epi Paleolithic economies in the Maghreb (ca. 20,000 to 5000 B.P.). In, J.D. Clark & S.A. Brandt (eds.), From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 41–56.

- D. Rubella, Environmentalism and Pi Paleolithic economies in the Maghreb (c. 20,000 to 5000 B.P.), in, J.D. Clark & S.A. Brandt (eds.), From Hunters to Farmers: Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 41–56

- "North Africa - Ancient North Africa". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "C. Michael Hogan, Mogador: Promontory Fort, The Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham". Megalithic.co.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- Sabatino Moscati, The Phoenicians, Tauris, ISBN 1-85043-533-2

- The Cambridge history of Africa. Vol. 2, From c.500 B.C. to A.D. 1050. Fage, J. D. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1978. p. 121. ISBN 9781139054560. OCLC 316278357.CS1 maint: others (link)

- C. Michael Hogan, Chellah, The Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham

- Data and map of Roman Banasa

- Georges Duby, Atlas Historique Mondial, Larousse Ed. (2000), pp.220 & 224 (ISBN 2702828655)

- Abun-Nasr 1987, p.33

- Abun-Nasr 1987, pp.33–34

- Abun-Nasr 1987, p.42

- G. Deverdun, "Bargẖawāṭa", Encyclopédie berbère, vol. 9, Edisud, 1991, pp.1360–1361

- Lightfoot, Dale R.; Miller, James A. (1996), "Sijilmassa: The rise and fall of a walled oasis in medieval Morocco" (PDF), Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 86: 78–101, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1996.tb01746.x, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2012, retrieved 10 October 2016

- "Northvegr – A History of the Vikings". Archived from the original on 17 August 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Hodgson, Marshall (1961), Venture of Islam, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 262

- Moroccan dynastic shurfa’‐hood in two historical contexts: idrisid cult and ‘Alawid power in : The Journal of North African Studies Volume 6, Issue 2, 2001

- Empires of Gold | Hour Three | Season 1 Episode 3 | Africa's Great Civilizations, retrieved 22 November 2019

- Maxime RODINSON, « ALMORAVIDES », Encyclopædia Universalis [en ligne], consulté le 23 octobre 2014. URL : http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/almoravides/

- Bernard Lugan, Histoire du Maroc ISBN 2-262-01644-5

- Concise Encyclopaedia of World History, by Carlos Ramirez-Faria, pp.23&676

- "Almohads | Berber confederation".

- Buresi, Pascal, and Hicham El Aallaoui. Governing the Empire: Provincial Administration in the Almohad Caliphate (1224–1269). Studies in the History and Society of the Maghrib, 3. Leiden: Brill, 2012. https://books.google.com/books?id=jcn8ugAACAAJ.

- Ira M. Lapidus, Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History, (Cambridge University Press, 2012), 414.

- "Marinid dynasty (Berber dynasty) – Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, (Columbia University Press, 1996), 41–42.

- (in French)"Les Merinides" on Universalis

- Niane, D.T. (1981). General History of Africa. IV. p. 91. ISBN 9789231017100. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, (Columbia University Press, 1996), 48.

- H. J. Kissling, Bertold Spuler, N. Barbour, J. S. Trimingham, F. R. C. Bagley, H. Braun, H. Hartel, The Last Great Muslim Empires, BRILL 1997, p.102

- E. George H. Joffé, North Africa: nation, state, and region, Routledge 1993, p. 19

- Michaël Peyron, « Dila‘ », in: Gabriel Camps (dir.), Encyclopédie berbère – Chp. XV. Édisud 1995, pp.2340–2345 (ISBN 2-85744-808-2)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Dr. Farooq's Study Resource Page". Globalwebpost.com. 20 June 2000. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- Convention on diplomatic protection signed in Madrid 1880

- "General Treaty Between Her Majesty and the Sultan of Morocco – EuroDocs". eudocs.lib.byu.edu. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-62469-5. OCLC 855022840.

- Gottreich, Emily R. Jewish space in the Morroccan city : a history of the mellah of Marrakech, 1550–1930. p. 54. OCLC 77066581.

- Rodrigue, Aron (2003). Jews and Muslims: Images of Sephardi and Eastern Jewries in Modern Times. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98314-1.

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-62469-5. OCLC 855022840.

- Frank E. Trout, Morocco's Boundary in the Guir-Zousfana River Basin, in: African Historical Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (1970), pp. 37–56, Publ. Boston University African Studies Center: « The Algerian-Moroccan conflict can be said to have begun in the 1890s when the administration and military in Algeria called for annexation of the Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt, a sizable expanse of Saharan oases that was nominally a part of the Moroccan Empire (...) The Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt oases had been an appendage of the Moroccan Empire, jutting southeast for about 750 kilometers into the Saharan desert »

- Frank E. Trout, Morocco's Saharan Frontiers, Droz (1969), p.24 (ISBN 9782600044950) : « The Gourara-Touat-Tidikelt complex had been under Moroccan domination for many centuries prior to the arrival of the French in Algeria »

- Furlong, Charles Wellington (September 1911). "The French Conquest Of Morocco: The Real Meaning Of The International Trouble". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXII: 14988–14999. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- Dennis Brogan, The Development of modern France, 1870–1939 (1940) 392–401.

- Kim Munholland, "Rival Approaches to Morocco: Delcasse, Lyautey, and the Algerian-Moroccan Border, 1903–1905." French Historical Studies 5#3 (1968): 328–343.

- الخديمي, علال, 1946-.... (2009). الحركة الحفيظية أو المغرب قبيل فرض الحماية الفرنسية الوضعية الداخلية و تحديات العلاقات الخارجية : 1912-1894. [د. ن.] OCLC 929569541.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- H. Z(J. W.) Hirschberg (1981). A history of the Jews in North Africa: From the Ottoman conquests to the present time / edited by Eliezer Bashan and Robert Attal. BRILL. p. 318. ISBN 978-90-04-06295-5.

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-139-62469-5. OCLC 855022840.

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-62469-5. OCLC 855022840.

- Repertory of Decisions of the International Court of Justice (1947-1992), P.453

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-139-62469-5. OCLC 855022840.

- De Azevedo, Raimondo Cagiano (1994) Migration and development co-operation.. Council of Europe. p. 25. ISBN 92-871-2611-9.

- Albert Habib Hourani, Malise Ruthven (2002). "A history of the Arab peoples". Harvard University Press. p.323. ISBN 0-674-01017-5

- Nelson, Harold D. (1985). Morocco, a Country Study. Headquarters, Department of the Army.

- "Morocco (10/04)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- HOFFMAN, KATHERINE E. (2010). "Berber Law by French Means: Customary Courts in the Moroccan Hinterlands, 1930-1956". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 52 (4): 851–880. doi:10.1017/S0010417510000484. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 40864899.

- Maghraoui, Driss (8 August 2014). "The goumiers in the Second World War: history and colonial representation". The Journal of North African Studies. 19 (4): 571–586. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.948309. ISSN 1362-9387.

- "زيارة محمد الخامس لطنجة.. أغضبت فرنسا وأشعلت المقاومة". Hespress (in Arabic). Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Text used in this cited section originally came from: Morocco profile from the Library of Congress Country Studies project.

- Al Jazeera Documentary الجزيرة الوثائقية (27 November 2017), رجل استرخص الموت – محمد الزرقطوني, retrieved 23 May 2019

- Burns, Jennifer. "Revolution of the King and the People in Morocco, 1950–1959: Records of the U.S. State Department Classified Files". Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- "Muḥammad V | sultan of Morocco". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- "Reign of Hassan II". https://www.globalsecurity.org/. 22 May 2020. External link in

|website=(help) - http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1192&context=twlj

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- "Marocanisation : Un système et des échecs". Aujourd'hui le Maroc (in French). Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- CIA Intelligence Report (September 1975). "The 1973 Arab-Israeli War. Overview and Analysis of the Conflict" (PDF). CIA Library Reading room. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Mohamed VI, King of Morocco". Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations. Gale. 2007.

- 13 March 2000 (13 March 2000). "Moroccans and Women: Two Rallies". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Moroccan feminist groups campaign to reform Moudawana (Personal Status Code/Islamic family law), 1992–2004 | Global Nonviolent Action Database". Nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Europe | Solution to island dispute 'closer'". BBC News. 19 July 2002. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Battle of Parsley Island ends". The Daily Telegraph. 20 July 2002. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- Schmickle, Sharon (17 December 2010). "The Kaplans in Morocco: Distinctive duo realizing a dream as they live politics and protocol 24/7". MinnPost. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

Bibliography

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil M. A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period, Cambridge University Press, 1987. ISBN 9780521337670.

- Chandler, James A. "Spain and Her Moroccan Protectorate, 1898–1927," Journal of Contemporary History 10 ( April 1975): 301–22.

- Pennell, C. R. Morocco Since 1830: A History, New York University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780814766774

- Pennell, C. R. Morocco: From Empire to Independence, Oneworld Publications, 2013. ISBN 9781780744551 (preview)

- Stenner, David. Globalizing Morocco: Transnational Activism and the Postcolonial State (Stanford UP, 2019). online review

- Terrasse, Henri. History of Morocco, Éd. Atlantides, 1952.

- Woolman, David. Rebels in the Rif: Abd-el-Krim and the Rif Rebellion (Stanford UP, 1967)

In French

- David Bensoussan, Il était une fois le Maroc : témoignages du passé judéo-marocain, Éd. du Lys, 2010. ISBN 2-922505-14-6.

- Bernard Lugan, Histoire du Maroc, Éd. Perrin, 2000. ISBN 2-262-01644-5

- Michel Abitbol, Histoire du Maroc, Éd. Perrin, 2009. ISBN 9782262023881

External links

- A short history of Morocco

- Morocco timeline from Worldstatesmen

- Early Twentiethth Century Timelines: Moroccan crises, 1903–1914

- The History of Morocco

- Historical map of Morocco – c. 1600

- Z. Brakez et al. "Human mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in the Moroccan population of the Souss area"