Treaty of Tordesillas

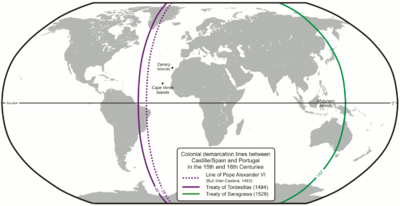

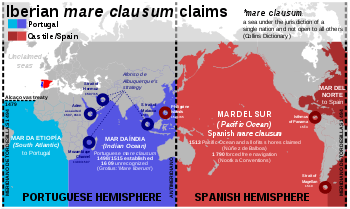

The Treaty of Tordesillas (Portuguese: Tratado de Tordesilhas [tɾɐˈtaðu ðɨ tuɾðeˈziʎɐʃ];[note 1] Spanish: Tratado de Tordesillas [tɾaˈtaðo ðe toɾðeˈsiʎas]), signed at Tordesillas in Spain on June 7, 1494, and authenticated at Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly-discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Empire (Crown of Castile), along a meridian 370 leagues[note 2] west of the Cape Verde islands, off the west coast of Africa. That line of demarcation was about halfway between the Cape Verde islands (already Portuguese) and the islands entered by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Castile and León), named in the treaty as Cipangu and Antilia (Cuba and Hispaniola).

| Treaty of Tordesillas | |

|---|---|

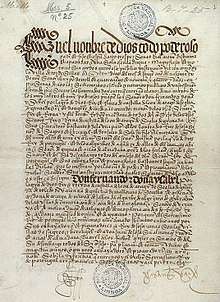

Front page of the Portuguese-owned treaty | |

| Created | 7 June 1494 in Tordesillas, Spain |

| Ratified | 2 July 1494 in Spain 5 September 1494 in Portugal 24 January 1505 or 1506 by Pope Julius II[1][2] |

| Location | Archivo General de Indias (Spain) Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (Portugal) |

| Signatories | Ferdinand II of Aragon Isabella I of Castile John, Prince of Asturias John II of Portugal[3] |

| Purpose | To divide trading and colonising rights for all newly discovered lands of the world located between Portugal and Castile (later applied between the Spanish Crown and Portugal) to the exclusion of other European nations |

The lands to the east would belong to Portugal and the lands to the west to Castile. The treaty was signed by Spain, 2 July 1494, and by Portugal, 5 September 1494. The other side of the world was divided a few decades later by the Treaty of Zaragoza, signed on 22 April 1529, which specified the antimeridian to the line of demarcation specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas. Originals of both treaties are kept at the General Archive of the Indies in Spain and at the Torre do Tombo National Archive in Portugal.[8]

This treaty would be observed fairly well by Spain and Portugal, despite considerable ignorance as to the geography of the New World; however, it omitted all of the other European powers, which generally ignored the treaty, particularly those that became Protestant after the Reformation.

The treaty was included by UNESCO in 2007 in its Memory of the World Programme.

Signing and enforcement

The Treaty of Tordesillas was intended to solve the dispute that had been created following the return of Christopher Columbus and his crew, who had sailed for the Crown of Castile. On his way back to Spain he first reached Lisbon, in Portugal. There he asked for another meeting with King John II to show him the newly discovered lands.

After learning of the Castilian-sponsored voyage, the Portuguese King sent a threatening letter to the Catholic Monarchs stating that by the Treaty of Alcáçovas signed in 1479 and confirmed in 1481 with the papal bull Æterni regis, that granted all lands south of the Canary Islands to Portugal, all of the lands discovered by Columbus belonged, in fact, to Portugal. Also, the Portuguese King stated that he was already making arrangements for a fleet (an armada led by Francisco de Almeida) to depart shortly and take possession of the new lands. After reading the letter the Catholic Monarchs knew they did not have any military power in the Atlantic to match the Portuguese, so they pursued a diplomatic way out. On 4 May 1493 Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia), an Aragonese from Valencia by birth, decreed in the bull Inter caetera that all lands west of a pole-to-pole line 100 leagues west of any of the islands of the Azores or the Cape Verde Islands should belong to Castile, although territory under Catholic rule as of Christmas 1492 would remain untouched.[9] The bull did not mention Portugal or its lands, so Portugal could not claim newly discovered lands even if they were east of the line. Another bull, Dudum siquidem, entitled Extension of the Apostolic Grant and Donation of the Indies and dated 25 September 1493, gave all mainlands and islands, "at one time or even still belonging to India" to Spain, even if east of the line.[10]

The Portuguese King John II was not pleased with that arrangement, feeling that it gave him far too little land—it prevented him from possessing India, his near term goal. By 1493 Portuguese explorers had reached the southern tip of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope. The Portuguese were unlikely to go to war over the islands encountered by Columbus, but the explicit mention of India was a major issue. As the Pope had not made changes, the Portuguese king opened direct negotiations with the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, to move the line to the west and allow him to claim newly discovered lands east of the line. In the bargain, John accepted Inter caetera as the starting point of discussion with Ferdinand and Isabella, but had the boundary line moved 270 leagues west, protecting the Portuguese route down the coast of Africa and giving the Portuguese rights to lands that now constitute the Eastern quarter of Brazil. As one scholar assessed the results, "both sides must have known that so vague a boundary could not be accurately fixed, and each thought that the other was deceived, [concluding that it was a] diplomatic triumph for Portugal, confirming to the Portuguese not only the true route to India, but most of the South Atlantic".[11]

The treaty effectively countered the bulls of Alexander VI but was subsequently sanctioned by Pope Julius II by means of the bull Ea quae pro bono pacis of 24 January 1506.[12] Even though the treaty was negotiated without consulting the Pope, a few sources call the resulting line the "Papal Line of Demarcation".[13]

Very little of the newly divided area had actually been seen by Europeans, as it was only divided via the treaty. Castile gained lands including most of the Americas, which in 1494 had little proven wealth. The easternmost part of current Brazil was granted to Portugal when in 1500 Pedro Álvares Cabral landed there while he was en route to India. Some historians contend that the Portuguese already knew of the South American bulge that makes up most of Brazil before this time, so his landing in Brazil was not an accident.[14] One scholar points to Cabral's landing on the Brazilian coast 12 degrees farther south than the expected Cape São Roque, such that "the likelihood of making such a landfall as a result of freak weather or navigational error was remote; and it is highly probable that Cabral had been instructed to investigate a coast whose existence was not merely suspected, but already known".[15]

The line was not strictly enforced—the Spanish did not resist the Portuguese expansion of Brazil across the meridian. However, the Catholic Monarchs attempted to stop the Portuguese advance in Asia, by claiming the meridian line ran around the world, dividing the whole world in half rather than just the Atlantic. Portugal pushed back, seeking another papal pronouncement that limited the line of demarcation to the Atlantic. This was given by Pope Leo X, who was friendly toward Portugal and its discoveries, in 1514 in the bull Praecelsae devotionis.[16]

For a period between 1580 and 1640, the treaty was rendered meaningless, as the Spanish King was also King of Portugal. It was superseded by the 1750 Treaty of Madrid which granted Portugal control of the lands it occupied in South America. However, the latter treaty was immediately repudiated by the Catholic Monarch. The First Treaty of San Ildefonso settled the problem, with Spain acquiring territories east of the Uruguay River and Portugal acquiring territories in the Amazon Basin.

Emerging Protestant maritime powers, particularly England and The Netherlands, and other third parties such as Roman Catholic France, did not recognize the division of the world between only two Roman Catholic nations brokered by the pope.[17]

Tordesillas meridian

The Treaty of Tordesillas only specified the line of demarcation in leagues from the Cape Verde Islands. It did not specify the line in degrees, nor did it identify the specific island or the specific length of its league. Instead, the treaty stated that these matters were to be settled by a joint voyage which never occurred. The number of degrees can be determined via a ratio of marine leagues to degrees applied to the Earth regardless of its assumed size, or via a specific marine league applied to the true size of the Earth, called "our sphere" by historian Henry Harrisse.[18]

- The earliest Aragonese opinion was provided by Jaime Ferrer in 1495 at the request of the Aragonese king and Castilian queen to those monarchs. He stated that the demarcation line was 18° west of the most central island of the Cape Verde Islands, which is Fogo according to Harrisse, having a longitude of 24°25′ west of Greenwich, hence Ferrer placed the line at 42°25′W on his sphere, which was 21.1% larger than our sphere. Ferrer also stated that his league contained 32 Olympic stades, or 6.15264 km according to Harrisse, thus Ferrer's line was 2,276.5 km west of Fogo at 47°37′W on our sphere.[19]

- The earliest surviving Portuguese opinion is on the Cantino planisphere of 1502. Because its demarcation line was midway between Cape Saint Roque (northeast cape of South America) and the mouth of the Amazon River (its estuary is marked Todo este mar he de agua doçe—"All of this sea is fresh water"—and its river is marked Rio grande, "great river"), Harrisse concluded that the line was at 42°30′W on our sphere. Harrisse believed the large estuary just west of the line on the Cantino map was that of the Rio Maranhão (this estuary is now the Baía de São Marcos and the river is now the Mearim), whose flow is so weak that its gulf does not contain fresh water.[20]

- In 1518 another Castilian opinion was provided by Martin Fernandez de Enciso. Harrisse concluded that Enciso placed his line at 47°24′W on his sphere (7.7% smaller than ours), but at 45°38′W on our sphere using Enciso's numerical data. Enciso also described the coastal features near which the line passed in a very confused manner. Harrisse concluded from this description that Enciso's line could also be near the mouth of the Amazon between 49°W and 50°W.[21]

- In 1524 the Castilian pilots (ships' captains) Thomas Duran, Sebastian Cabot (son of John Cabot), and Juan Vespuccius (nephew of Amerigo Vespucci) gave their opinion to the Badajoz Junta, whose failure to resolve the dispute led to the Treaty of Saragossa. They specified that the line was 22° plus nearly 9 miles west of the center of Santo Antão (the westernmost Cape Verde island), which Harrisse concluded was 47°17′W on their sphere (3.1% smaller than ours) and 46°36′W on our sphere.[22]

- In 1524 the Portuguese presented a globe to the Badajoz Junta on which the line was marked 21°30′ west of Santo Antão (22°6′36″ on our sphere).[23]

Antimeridian: Moluccas and Treaty of Zaragoza

Initially, the line of demarcation did not encircle the Earth. Instead, Spain and Portugal could conquer any new lands they were the first to discover, Spain to the west and Portugal to the east, even if they passed each other on the other side of the globe.[24] But Portugal's discovery of the highly valued Moluccas in 1512 caused Spain to argue in 1518 that the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the Earth into two equal hemispheres. After the surviving ships of Magellan's fleet visited the Moluccas in 1521, Spain claimed that those islands were within its western hemisphere. In the early 16th century, the Treaty between Spain and Portugal, concluded at Vitoria; February 19, 1524 and called for the Badajoz Junta to meet in 1524, at which the two countries tried to reach an agreement on the anti-meridian but failed.[25] They finally agreed in a treaty signed at Zaragoza that Spain would relinquish its claims to the Moluccas upon the payment of 350,000 ducats of gold[note 3] by Portugal to Spain. To prevent Spain from encroaching upon Portugal's Moluccas, the anti-meridian was to be 297 1⁄2 leagues or 17° to the east of the Moluccas, passing through the islands of Las Velas and Santo Thome.[29] This distance is slightly smaller than the 300 leagues determined by Magellan as the westward distance from los Ladrones to the Philippine island of Samar, which is just west of due north of the Moluccas.[30]

The Moluccas are a group of islands west of New Guinea. However, unlike the large modern Indonesian archipelago of the Maluku Islands, to 16th-century Europeans the Moluccas were a small chain of islands, the only place on Earth where cloves grew, just west of the large north Malukan island of Halmahera (called Gilolo at the time). Cloves were so prized by Europeans for their medicinal uses that they were worth their weight in gold.[31][32] 16th- and 17th-century maps and descriptions indicate that the main islands were Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian and Bacan, although the last was often ignored even though it was by far the largest island.[33][34][35] The principal island was Ternate at the chain's northern end (0°47′N, only 11 kilometres (7 mi) in diameter) on whose southwest coast the Portuguese built a stone fort (Forte de São João Baptista de Ternate) during 1522–23,[36] which could only be repaired, not modified, according to the Treaty of Saragossa. This north–south chain occupies two degrees of latitude bisected by the equator at about 127°24′E, with Ternate, Tidore, Moti, and Makian north of the equator and Bacan south of it.

Although the treaty's Santo Thome island has not been identified, its "Islas de las Velas" (Islands of the Sails) appear in a 1585 Spanish history of China, on the 1594 world map of Petrus Plancius, on an anonymous map of the Moluccas in the 1598 London edition of Linschoten, and on the 1607 world map of Petro Kærio, identified as a north–south chain of islands in the northwest Pacific, which were also called the "Islas de los Ladrones" (Islands of the Thieves) during that period.[37][38][39] Their name was changed by Spain in 1667 to "Islas de las Marianas" (Mariana Islands), which include Guam at their southern end. Guam's longitude of 144°45′E is east of the Moluccas' longitude of 127°24′E by 17°21′, which is remarkably close by 16th-century standards to the treaty's 17° east. This longitude passes through the eastern end of the main north Japanese island of Hokkaidō and through the eastern end of New Guinea, which is where Frédéric Durand placed the demarcation line.[40] Moriarty and Keistman placed the demarcation line at 147°E by measuring 16.4° east from the western end of New Guinea (or 17° east of 130°E).[41] Despite the treaty's clear statement that the demarcation line passes 17° east of the Moluccas, some sources place the line just east of the Moluccas.[42][43][44]

The Treaty of Saragossa did not modify or clarify the line of demarcation in the Treaty of Tordesillas, nor did it validate Spain's claim to equal hemispheres (180° each), so the two lines divided the Earth into unequal hemispheres. Portugal's portion was roughly 191° whereas Spain's portion was roughly 169°. Both portions have a large uncertainty of ±4° because of the wide variation in the opinions regarding the location of the Tordesillas line.

Portugal gained control of all lands and seas west of the Saragossa line, including all of Asia and its neighboring islands so far "discovered", leaving Spain most of the Pacific Ocean. Although the Philippines were not named in the treaty, Spain implicitly relinquished any claim to them because they were well west of the line. Nevertheless, by 1542, King Charles V decided to colonize the Philippines, judging that Portugal would not protest because the archipelago had no spices. Although a number of expeditions sent from New Spain arrived in the Philippines, they were unable to establish a settlement because the return route across the Pacific was unknown. King Philip II succeeded in 1565 when he sent Miguel López de Legazpi and Andrés de Urdaneta, establishing the initial Spanish trading post at Cebu and later founding Manila in 1571.

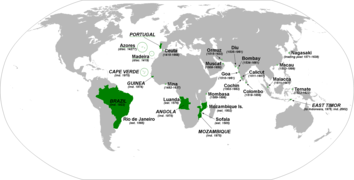

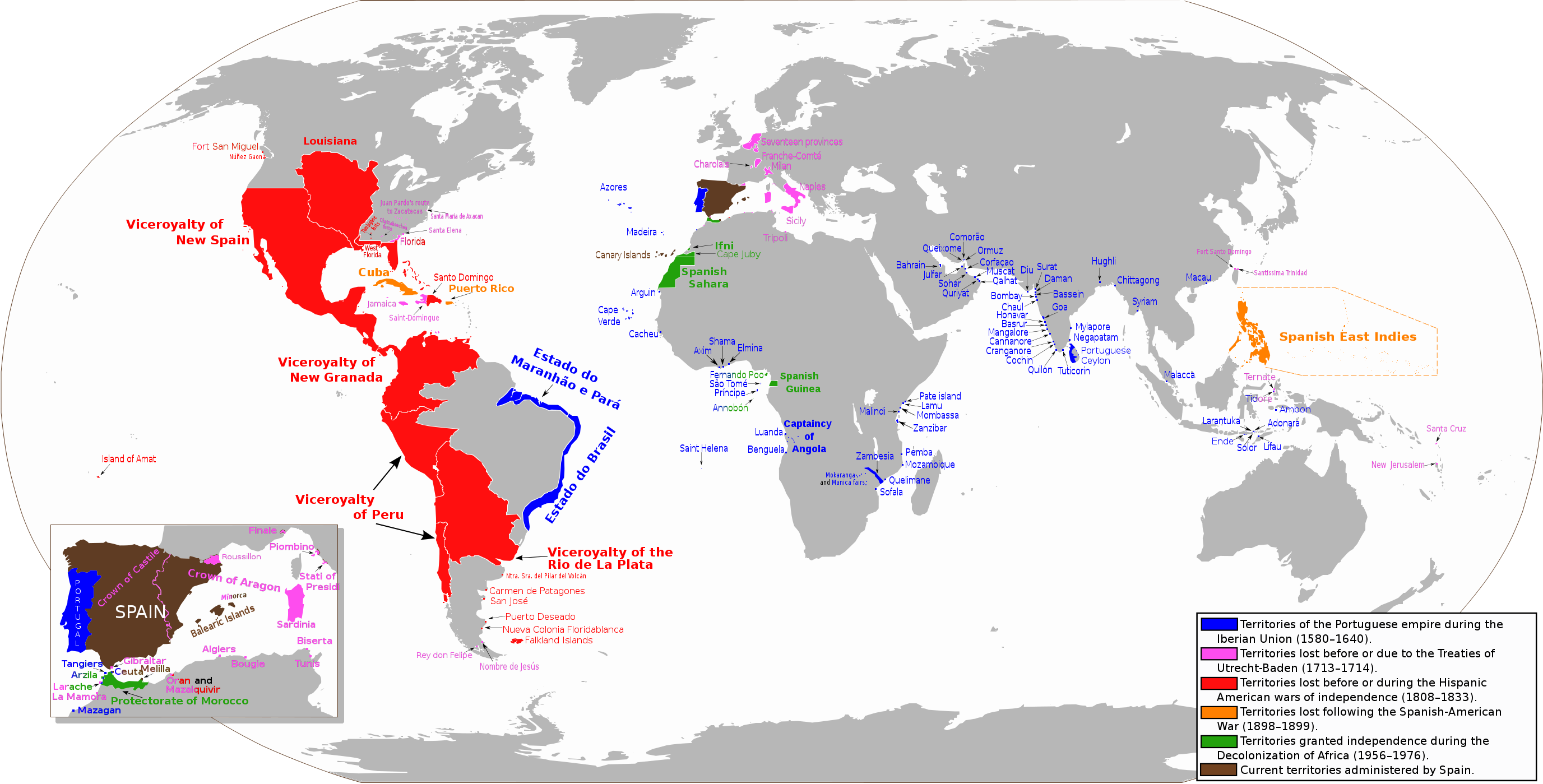

Besides Brazil and the Moluccas, Portugal eventually controlled Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea, and São Tomé and Príncipe (among other territories and bases) in Africa; several bases or territories as Muscat, Ormus and Bahrain in the Persian Gulf, Goa, Bombay and Daman and Diu (among other coastal cities) in India; Ceylon, and Malacca, bases in present-day Indonesia as Makassar, Solor, Ambon, and Portuguese Timor, the entrepôt-base of Macau and the entrepôt-enclave of Dejima (Nagasaki) in the Far East.

Spain, on the other hand, would control vast western regions in the Americas, in areas ranging from the present-day United States to present-day Argentina, an empire that would extend to the Philippines, and bases in Ternate and Formosa (17th century).

| Portuguese and Spanish empires (anachronous world maps) | ||

|---|---|---|

Spanish Empire alongside Iberian Union |

Iberian Union (1581–1640) | |

Effect on other European powers

The treaty was important in dividing Latin America, as well as establishing Spain in the western Pacific. However, it quickly became obsolete in North America, and later in Asia and Africa, where it affected colonization. It was ignored by other European nations, and with the decline of Spanish and Portuguese power, the home countries were unable to hold many of their claims, much less expand them into poorly explored areas. Thus, with sufficient backing, it became possible for any European state to colonize open territories, or those weakly held by Lisbon or Madrid. With the fall of Malacca to the Dutch, the VOC (Dutch East India Company) took control of Portuguese possessions in Indonesia, claiming Western New Guinea and Western Australia, as New Holland. Eastern Australia remained in the Spanish half of the world until claimed for Britain by James Cook in 1770. The attitude towards the treaty that other governments had was expressed in a statement attributed to France's King Francis I, "Show me Adam's will!"[45]

Treaty of Madrid

On January 13, 1750, King John V of Portugal and Ferdinand VI of Spain signed the Treaty of Madrid, in which both parties sought to establish the borders between Brazil and Spanish America, admitting that the Treaty of Tordesillas, as it had been envisioned in 1494 had been superseded, and was considered void. Spain was acknowledged sovereignty over the Philippines, while Portugal would get the territory of the Amazon River basin. Portugal would relinquish the colony of Sacramento, on the northern bank of the River Plata in modern-day Uruguay, while getting the territory of the Seven Missions.[46]

Modern claims

The Treaty of Tordesillas was invoked by Chile in the 20th century to defend the principle of an Antarctic sector extending along a meridian to the South Pole, as well as the assertion that the treaty made Spanish (or Portuguese) all undiscovered land south to the Pole.[47]

Indonesia took possession of Netherlands New Guinea in 1962, supporting its claim by stating the Empire of Majapahit had included western New Guinea, and that it was part of the Treaty of Tordesillas.

The Treaty of Tordesillas was also invoked by Argentina in the 20th century as part of its claim to the Falkland Islands.[48]

Notes

- In the European Portuguese pronunciation. Brazilians might variously pronounce it as [tɾɐˈtadʊ dʑɪ toɾdeˈziʎəs] in São Paulo, [tɾəˈtadu dʑi to̞ʀde̞ˈziʎəɕ] in Rio de Janeiro and [tɾaˈtadu dʑi tɔʁdɛˈziʎəs] in Salvador and [tɾɐˈtadu di tɔɦde̞ˈziʎəs] in Recife.

-

370 leagues equals 2,193 kilometers, 1,362 statute miles, or 1,184 nautical miles.

The figures use the legua náutica (nautical league) of four Roman miles, totaling 5.926 km, which was used by Spain in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries for navigation.[4] In 1897, Henry Harrise noted that Jaime Ferrer, the expert consulted by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, stated that a league was four miles of six stades each.[5] Modern scholars agree that the geographic stade was the Roman or Italian stade, not any of several other Greek stades, supporting those figures.[6][7] Harrise is in the minority when he uses the stade of 192.27 m marked within the stadium at Olympia, Greece, resulting in a league (32 stades) of 6.153 km, 3.8% larger. - 350,000 ducats of gold weighs about 1,230 kg at 3.521 grams of gold per ducat. Gold ducats are small coins, about 20 mm (0.79 in) in diameter (roughly circular), but very thin at about 0.8 mm (0.031 in) thick (obverse relief to reverse relief).[26][27][28]

References

Citations

- Horst Pietschmann, Atlantic history : history of the Atlantic System 1580-1830, Göttingen : Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2002, p. 239

- Parise, Agustín (23 January 2017). Ownership Paradigms in American Civil Law Jurisdictions: Manifestations of the Shifts in the Legislation of Louisiana, Chile, and Argentina (16th-20th Centuries). BRILL. p. 68. ISBN 9789004338203. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Emma Helen Blair, ed., The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803 (Cleveland, Ohio: 1903). Frances Gardiner Davenport, ed., European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies to 1648 (Washington, DC: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1917), 100.

- Chardon, Roland (1980). "The linear league in North America". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 70 (2): 129–153 [pp. 142, 144, 151]. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1980.tb01304.x. JSTOR 2562946.

- Harrisse, pp. 85–97, 176–190.

- Newlyn Walkup, Eratosthenes and the mystery of the stades

- Engels, Donald (1985). "The length of Eratosthenes' stade". American Journal of Philology. 106 (3): 298–311. doi:10.2307/295030. JSTOR 295030.

- Davenport, 85, 171.

- Pope Alexander VI (4 May 1493). – via Wikisource.

- Pope Alexander VI (25 September 1493). (in Latin) – via Wikisource.

- Parry, J. H. (1973). The Age of Reconnaissance: Discovery, Exploration, and Settlement, 1450–1650. London: Cardinal. p. 194. ISBN 0-297-16603-4.

- Davenport, ed., 107–111.

- Leslie Ronald Marchant, The Papal Line of Demarcation and Its Impact in the Eastern Hemisphere on the Political Division of Australia, 1479–1829 (Greenwood, Western Australia: Woodside Valley Foundation, 2008) ISBN 978-1-74126-423-4.

- Crow, John A. (1992). The Epic of Latin America (Fourth ed.). University of California Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-520-07723-7.

- Parry, Age of Reconnaissance p. 198.

- Parry, Age of Reconnaissance p. 202.

- Parry, Age of Reconnaissance p. 205.

- Henry Harrisse, The Diplomatic History of America: Its first chapter 1452—1493—1494 (London: Stevens, 1897). pp. 194

- Harrisse, pp. 91–97, 178–190.

- Harrisse, pp. 100–102, 190–192.

- Harrisse, pp. 103–108, 122, 192–200.

- Harrisse, pp. 138–139, 207–208.

- Harrisse, pp. 207–208.

- Edward Gaylord Bourne, "Historical Introduction", in Blair.

- Emma Helen Blair, The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803, part 2

- 1497 Spanish ducat

- Gold Ducat - Specifications, APMEX

- Anatomy of a Coin, United States Mint

- Emma Helen Blair, The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803, part 3

- Lord Stanley of Alderley, The first voyage round the world, by Magellan, London: Hakluyt, 1874, p. 71

- Andaya, pp. 1–3

- Corn, p. xxiv. "I split the nut, once more valuable than gold."

- Gavan Daws and Marty Fujita, Archipelago: The Islands of Indonesia, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 98, ISBN 0-520-21576-1 (early 1500s).

- "The Portuguese in the Moluccas and in the Lesser Sunda Islands by Marco Ramerini, 1600s". Colonialvoyage.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- Lord Stanley of Alderley, The first voyage round the world, by Magellan, London: Hakluyt Society, 1874, pp. 126–27.

- Andaya, p. 117. After the Iberian Union (1580–1640) and the effective Dutch conquest of the Moluccas (1605–1611, pp. 152–3), the fort was destroyed by the Spanish in 1666 during their retreat to the Philippines. (p. 156)

- Knowlton, p.341. The islands were named both las Velas and los Ladrones in a quote from Father Juan González de Mendoza in Historia de las cosas más notables, ritos y costumbres del gran Reino de la China (History of the most remarkable things, rites and customs of the great Kingdom of China, 1585).

- Cortesao, p.224, with detailed maps naming each island on several maps.

- ed. John O. E. Clark, 100 Maps (New York: Sterling, 2005) p. 115, ISBN 1-4027-2885-9.

- Le Réseau Asie (2006-09-15). "The cartography of the Orientals and Southern Europeans in the beginning of the western exploration of South-East Asia from the middle of the XVth century to the beginning of the XVIIth century by Frédéric Durand". Reseau-asie.com. Archived from the original on 2009-10-03. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- "Philip II Orders the Journey of the First Manila Galleon". The Journal of San Diego History (Volume 12, Number 2 ed.). April 1966. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- Lines in the sea by Giampiero Francalanci and others, p.3 about 129°E or only 1°30′ east of the Moluccas.

- Lines of Demarcation 1529 about 134°E or 6°30′ east of the Moluccas.

- Infoblatt Das Zeitalter der großen Entdeckungsfahrten about 135°E or 7°30′ east of the Moluccas.

- Miller, James Rodger (2000-06-01). Skyscrapers hide the heavens: a history of Indian-white relations in Canada. p. 20. ISBN 9780802081537. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- José Damião Rodrigues, Pedro Aires Oliveira (2014) História da Expansão e do Império Português ed. Esfera dos Livros, p.266-267

- "National Interests And Claims In The Antarctic" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- Laver, Roberto (2001). The Falklands/Malvinas case. Springer. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-90-411-1534-8.

Bibliography

- Edward G. Bourne, 'The History and Determination of the Line of Demarcation by Pope Alexander VI, between the Spanish and Portuguese Fields of Discovery and Colonization', American Historical Association, Annual Report for 1891, Washington, 1892; Senate Miscellaneous Documents, Washington, Vol.5, 1891–92, pp. 103–30.

- James R Akerman, The Imperial Map (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009) 138.

- Leonard Y. Andaya, The world of Maluku: Eastern Indonesia in the early modern period (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8248-1490-8.

- Emma Helen Blair, ed., The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803 (vol 1 of 55) (Cleveland, Ohio: 1903-1909), containing complete English translations of both treaties and related documents.

- Stephen R. Bown, 1494: How a family feud in medieval Spain divided the world in half (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2012) ISBN 978-0-312-61612-0.

- Charles Corn, The Scents of Eden: A Narrative of the Spice Trade, (New York: Kodansha, 1998), ISBN 1-56836-202-1.

- Cortesao, Armando (1939). "Antonio Pereira and his map of circa 1545". Geographical Review. 29: 205–225. doi:10.2307/209943. JSTOR 209943.

- Frances Gardiner Davenport, ed., European Treaties bearing on the History of the United States and its Dependencies to 1648 (Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1917/1967).

- Translation of the Treaty of Tordesillas by Davenport.

- Henry Harrisse, The Diplomatic History of America: Its first chapter 1452—1493—1494 (London: Stevens, 1897).

- Knowlton, Edgar C. (1963). "China and the Philippines in El Periquillo Sarniento". Hispanic Review. 31 (4): 336–347. doi:10.2307/472212. JSTOR 472212.

- Waisberg, Tatiana, "The Treaty of Tordesillas and the (Re)Invention of International Law in the Age of Discovery" Journal of Global Studies, No 47, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of Tordesillas (Tratado de Tordesillas). |

- Treaty of Tordesillas (about.com)

- Treaty of Tordesillas (Portuguese) from Archivo General de Indias

- Treaty of Tordesillas English translation from Blair—BROKEN LINK

- Compact Between the Catholic Sovereigns and the King of Portugal Regarding the Demarcation and the Division of the Ocean Sea English translation from Blair—BROKEN LINK