Alhucemas landing

The Alhucemas landing (Spanish: Desembarco de Alhucemas; also known as Al Hoceima landing) was a landing operation which took place on 8 September 1925 at Alhucemas by the Spanish Army and Navy and, in lesser numbers, an allied French contingent, that would put an end to the Rif War. It is considered the first amphibious landing in history involving the use of tanks and massive seaborne air support.[2]

| Alhucemas landing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Rif War | |||||||

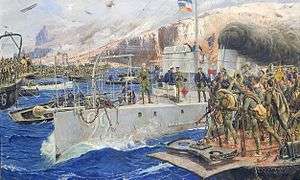

Desembarco de Alhucemas, José Moreno Carbonero | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

13,000 17 tanks 3 battleships 5 light cruisers 1 protected cruiser 1 aircraft carrier 2 destroyers 2 monitors 7 gunboats 18 patrol boats 6 torpedo boats 4 tugs 58 transport ships 160 aircraft | 9,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 309 killed and wounded[1] | 700 killed and wounded | ||||||

The operations consisted on disembarking a force of 13,000 Spanish soldiers transported from Ceuta and Melilla by a combined Spanish-French naval fleet. The commander of the operation was the then dictator of Spain, general Miguel Primo de Rivera, and, as the executive head of the landing forces at the beach of Alhucemas bay, general José Sanjurjo, under whose orders were the columns of the chief generals of the brigades of Ceuta and Melilla, Leopoldo Saro Marín and Emilio Fernández Pérez, respectively. Among the participating officers, there was the then colonel Francisco Franco who, for his leadership of the Spanish Legion troops, was promoted to brigadier general.

Background

After the Battle of Annual in July 1921, the Spanish army was unable to regain lost territory. It undertook a containment policy aimed at preventing the expansion of the rebel zone, executed by limited military actions of local nature. In parallel, the Minister of War ordered the creation of an inquiry commission, led by General Juan Picasso González, which developed the report known as Expediente Picasso. Political forces, public opinion, and the army were divided between supporters of leaving the Protectorate and advocates of restarting the military operations as soon as possible.

In September 1923, the coup of general Primo de Rivera occurred, who at first supported the abandonment of the Protectorate. In 1924 and after new attacks by Abd el Krim, which caused a Spanish retreat to the areas of Tetuan, Ceuta and Melilla, he changed to strongly supporting an offensive to defeat the Riffian leader and restore Spanish authority in the Protectorate.

Planning

In April 1925 a crucial event occurred: Abd el-Krim, confident of his success against the Spanish, attacked the French zone of the Protectorate. This opened the doors for a Spanish-French agreement to make a common front against the Riffians. To this end, in June 1925 the Madrid Conference took place, which set out the necessary actions. Among the agreements reached there were the plan for a Spanish landing on the Alhucemas bay, with the cooperation and support of a combined air and naval Spanish-French force.

Alhucemas, home of the kabyle (tribe) of Beni Ouriaghel, to which Abd el Krim belonged, was the focus of the ongoing Rif rebellion. All Spanish land operations, included the Disaster of Annual in 1921, aimed at the occupation of Alhucemas, but all of them failed, mainly due to too long resupply lines.

The operation initially proposed the landing of 18,000 men, although 13,000 would eventually be landed, to build-up a base of operations in the area of Al Hoceima and deal with an estimated force of 11,000 Riffians. This operation was the first amphibious action that involved Spain in the modern era which posed a concern to the Spanish authorities. As if it was not enough, the terrain presented difficulties in performing the landing, besides being a well-known area for the Riffians. Aware of the risk, Primo de Rivera carefully planned the landing.

The probable knowledge of the planned landing prompted Abd el Krim to fortify the area, placing artillery and mines. These circumstances forced the Spanish command to change the landing site, choosing Cebadilla Beach and Cala del Quemado, west of the Bay of Al Hoceima. The first major effort to seize the beachhead would be exercised in those beaches; once the landing would be successfully achieved, the second effort would be either in some of the adjacent creeks or a deepening and expansion of the initial beachhead, depending on the circumstances.

References

Notes

- According to the official report, quoted by Martín Tornero (1991).

- Douglas Porch, "Spain's African Nightmare," MHQ: Quarterly Journal of Military History (2006) 18#2 pp 28–37.

Bibliography

- Bachoud, André: Los españoles ante las campañas de Marruecos. Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1988

- Goded, Manuel: Marruecos. Etapas de la pacificación. Madrid, C.I.A.P., 1932

- Hernández Mir, Francisco: Del desastre a la victoria. Madrid, Imprenta Hispánica, 1927

- Larios de Medrano, Justo: España en Marruecos. Historia secreta de la campaña. Madrid, Stampa, 1925

- Martín Tornero, Antonio (1991): El desembarco de Alhucemas. Organización, ejecución y consecuencias. En: Revista de Historia militar, año XXV, nº 70. Madrid, Servicio Histórico Militar. ISSN 0482-5748

- Matthieu, Roger: Mémoires d' Abd-el-Krim. París, Librairie des Champs-Elysées, 1927

- Ros Andreu, Juan Bautista: La conquista de Alhucemas. Novela histórica. Las Palmas, Tipografía La provincia, 1932

- Woolman, David S.: Abd-el-Krim y la guerra del Rif. Barcelona, Oikos-Tau, 1988

- Domínguez Llosá, Santiago: El desembarco de Alhucemas. 2002. ISBN 978-84-338-2919-1