Spanish Guinea

Spanish Guinea (Spanish: Guinea Española) was a set of insular and continental territories controlled by Spain since 1778 in the Gulf of Guinea and on the Bight of Bonny, in Central Africa. It gained independence in 1968 and is known as Equatorial Guinea.

Province of the Gulf of Guinea | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1778–1968 | |||||||||||||

.svg.png) Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||

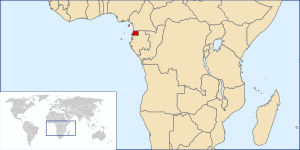

Location of Spanish Guinea in central Africa. | |||||||||||||

| Status | Colony of Spain (1778-1968) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Santa Isabel | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish | ||||||||||||

| Head of State | |||||||||||||

• 1778–1788 | King Carlos III (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1936–1968 | Caudillo Francisco Franco (last) | ||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||

• 1778-1781 | Felipe Freyre | ||||||||||||

• 1966-1968 | Víctor Suances Díaz del Río | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 11 March 1778 | ||||||||||||

| 12 October 1968 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish peseta | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Equatorial Guinea |

|

| Chronological |

History

18th—19th centuries

The Spanish colony in the Guinea region was established in 1778, by the Treaty of El Pardo between the Spanish Empire and the Kingdom of Portugal. Between 1778 and 1810, Spain administered the territory of Equatorial Guinea via its colonial Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, based in Buenos Aires (in present-day Argentina).

From 1827 to 1843, the United Kingdom had a base on Bioko to combat the continuing Atlantic slave trade conducted by Spain and illegal traders.[1] Based on an agreement with Spain in 1843, Britain moved its base to its own colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa. In 1844, on restoration of Spanish sovereignty, it became known as the "Territorios Españoles del Golfo de Guinea".

20th century

Spain had never undertaken colonial settlement of the large area in the Bight of Biafra to which it had treaty rights. The French expanded their occupation at the expense of the area claimed by Spain. By the treaty of Paris in 1900, Spain was left with the continental enclave of Río Muni, 26,000 km2 of the 300,000 stretching east to the Ubangi river, which the Spaniards had previously claimed.[2]

Agricultural economy

Toward the end of the 19th century Spanish, Portuguese, German and Fernandino planters started developing large cacao plantations on the island of Fernando Po.[3] With the indigenous Bubi population decimated by disease and forced labour, the island's economy came to depend on imported agricultural contract workers.

A labour treaty was signed with the Republic of Liberia in 1914; the transport of up to 15,000 workers by sea was orchestrated by the German Woermann-Linie, the major shipping company.[4] In 1930 an International Labour Organization (ILO) commission discovered that Liberian contract workers had ‘‘been recruited under conditions of criminal compulsion scarcely distinguishable from slave raiding and slave trading’’.[5] The government prohibited recruiting of Liberian workers for Spanish Guinea.

The persisting labour shortage in the cacao, coffee and logging industries led to a booming trade in illegal canoe-based smuggling of Igbo and Ibibio workers from the Eastern Provinces of Nigeria. The number of clandestine contract workers on the island of Fernando Po grew to 20,000 in 1942.[6] A labour treaty was signed with the British Crown in the same year. This led to a continuous stream of Nigerian workers going to Spanish Guinea. By 1968 at the time of independence, almost 100,000 ethnic Nigerians were living and working in Spanish Guinea.[7]

Colony of Spanish Guinea

Between 1926 and 1959, the Crown united Bioko and Río Muni as the "colony of Spanish Guinea". The economy was based on the exploitation of the commodity crops of cacao and coffee, produced at large plantations, in addition to logging concessions. Owners of these companies hired mostly immigrant contract labour from Liberia, Nigeria, and Cameroon.[6] Spain mounted military campaigns in the 1920s to subdue the indigenous Fang people, as Liberia was trying to reduce recruiting of its workers. The Crown established garrisons of the Colonial Guard throughout the enclave by 1926, and the whole colony was considered 'pacified' by 1929.[8]

Río Muni had a small population, officially put at a little over 100,000 in the 1930s. Its people could easily escape over the borders into Cameroon or Gabon. Moreover, the timber companies needed growing amounts of labour, and the spread of coffee cultivation offered an alternative means of paying taxes.

The island of Fernando Po continued to suffer from labour shortages. The French only briefly permitted recruitment in Cameroon. Planters began to recruit Igbo laborers, who were smuggled in canoes from Calabar, Nigeria. Fernando Po was developed after the Second World War as one of Africa's most productive agricultural areas.[2]

Decolonisation

The post-war political history of Spanish Guinea had three fairly distinct phases. From 1946 to 1959, it had the status of a "province", having been raised from "colony", after the Portuguese Empire made overtures to take it over. From 1960 to 1968, Spain tried a system of partial decolonisation to keep the province within the Spanish territorial system, which failed due to continued anti-colonial activity by Guineans. On 12 October 1968, Spain conceded the independence of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea. Francisco Macías Nguema was elected as president.[9]

Colonial demographics

The population of the Colony of Spanish Guinea was stratified (before slavery was abolished). The system was somewhat similar to the one operating in the French, English and Portuguese colonies in the rest of Africa:[10]

- Peninsulares — White Spanish population, whose immigration was regulated by the Spanish government.

- Emancipados — Black African population, assimilated into the Peninsulares' culture via Spanish Catholic educations. Some were descended from freed Cuban slaves, repatriated to Africa after emancipation and abolition of slavery by the Spanish Royal Orders of 13 September 1845 (voluntary), and of 20 June 1861 (deported). The latter group included mestizos (indigenous-European) and mulattoes (African-European), mixed-race descendants who had been acknowledged by a white Peninsular father.[11]

- Fernandinos — Creole peoples, multi-ethnic or multi-race populations, often speaking the local Pidgin English of Spanish Guinea's island of Fernando Po (now known as Bioko).

- "Individuals of colour" under patronage — included the majority of the indigenous Black African people, and those mestizos−mulattoes who were not acknowledged by white fathers and were being deported from the Americas. Of the indigenous ethnic groups in Guinea, most were Bubi and Bantu peoples such as the Fang of Rio Muni.

- Others — primarily Nigerian, Cameroonian, Han Chinese, and Indian peoples who were hired as contract laborers under types of indentures.

See also

References

- "Fernando Po", Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911.

- William Gervase Clarence-Smith, 1986 "Spanish Equatorial Guinea, 1898-1940", in The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1905 to 1940 Ed. J. D. Fage, A. D. Roberts, & Roland Anthony Oliver. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press>"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-20. Retrieved 2013-09-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Clarence-Smith, William G. "African and European Cocoa Producers on Fernando Poo, 1880s to 1910s." Journal of African History 35 (1994): 179-179.

- Sundiata, Ibrahim K. From Slaving to Neoslavery: the Bight of Biafra and Fernando Po in the Era of Abolition, 1827-1930, Madison, WI: Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

- "Slavery Conditions in Liberia", The Times 27 October 1930. http://www.opensourceguinea.org/2012/12/slavery-conditions-in-liberia-times-27.html

- Enrique Martino, “Clandestine Recruitment Networks in the Bight of Biafra: Fernando Pó’s Answer to the Labour Question, 1926–1945.” in International Review of Social History, 57, pp 39-72. http://www.opensourceguinea.org/2013/03/enrique-martino-clandestine-recruitment.html

- Pélissier, René. Los Territorios Espanoles De Africa. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1964.

- Nerín, Gustau. "La última selva de España:" antropófagos, misioneros y guardias civiles. Crónica de la conquista de los Fang de la Guinea Española, 1914–1930 (The last jungle of Spain: cannibals, missionaries and civil guards. Chronicle of the conquest of the Fang of Spanish Guinea, 1914–1930), Catarata, 2010.

- Campos, Alicia. "The decolonization of Equatorial Guinea: the relevance of the international factor", Journal of African History (2003): 95–116.

- Anuario del Instituto Cervantes (2005). Panorama de la literatura en español en Guinea Ecuatorial, Justo Bolekia Boleká, Introducción histórica

- Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie V, Hª Contemporánea, t. 11, 1998, págs. 113-138, "Penología e indigenismo en la antigua Guinea española" Archived 2011-05-30 at the Wayback Machine, Pedro María Belmonte Medina