Tidore

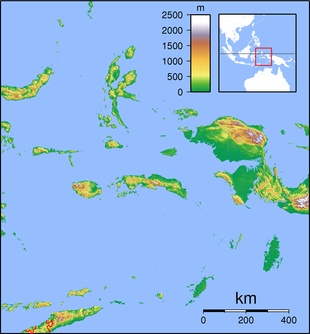

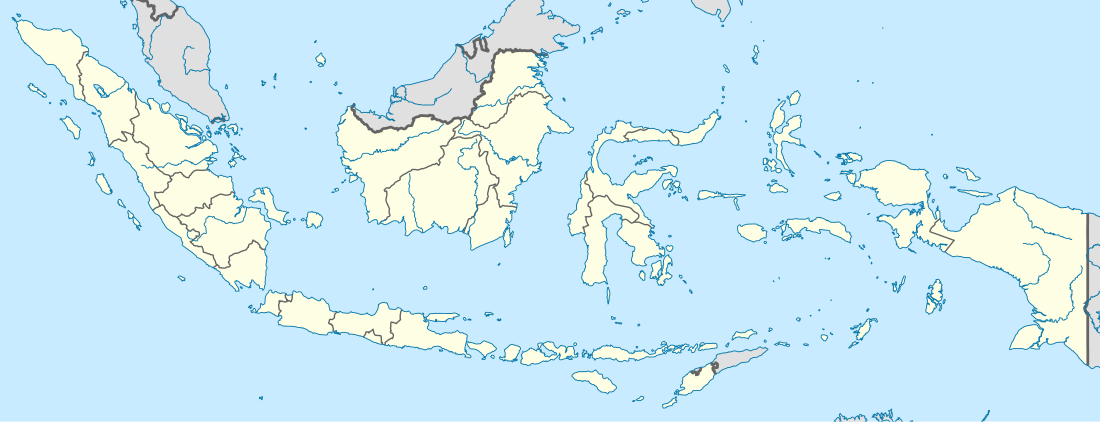

Tidore (Indonesian: Kota Tidore Kepulauan) is a city, island, and archipelago in the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia, west of the larger island of Halmahera. In the pre-colonial era, the Sultanate of Tidore was a major regional political and economic power, and a fierce rival of nearby Ternate, just to the north.

Tidore Kota Tidore Kepulauan | |

|---|---|

Tidore Island, as seen from Ternate Island. | |

Seal | |

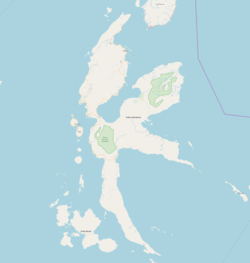

Location within Maluku Islands | |

| Coordinates: 0°41′N 127°24′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Maluku Islands |

| Province | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ali Ibrahim |

| • Vice Mayor | Muhammad Senin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,550.37 km2 (598.60 sq mi) |

| Population (2015) | |

| • Total | 48,678 |

| • Density | 31/km2 (81/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Indonesia Eastern Time) |

| Postcodes | 9xxxx |

| Area code | (+62) 921 |

| Vehicle registration | DG |

| Website | tidorekota.go.id |

Geography

Tidore Island consists of a large stratovolcano which rises from the seafloor to an elevation of 1,730 m (5,676 ft) above sea level at the conical Mount Kie Matubu on the south end of the island. The northern side of the island contains a caldera, Sabale, with two smaller volcanic cones within it.

Soasio is Tidore's capital. It has its own port, Goto, and it lies on the eastern edge of the island. It has a mini bus terminal and a market. The sultan's palace was rebuilt with completion in 2010.[1]

History

Tidore was the center of a spice-funded sultanate that arose in the 15th century It spent much of its history in the shadow of Ternate, another sultanate with which it had a dualistic relationship.[2]

Islam spread to Tidore around the late 15th century but Islamic influence in the area can be traced further back to the late 14th century.[3]

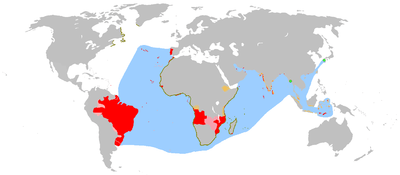

The sultans of Tidore ruled most of southern Halmahera, and, at times, controlled Buru, East Ceram and many of the islands off the coast of New Guinea.[4] Tidore established an alliance with the Spanish in the sixteenth century, and Spain had several forts on the island. There was mutual distrust between the Tidorese and the Spaniards but for the Tidorese the Spanish presence was helpful in resisting the incursions of the Ternateans and their ally, the Dutch, who had a fort on Ternate. For the Spanish, backing the Tidore state helped check the expansion of Dutch power that threatened their nearby Asia-Pacific interests, provided a useful base right next to the centre of Dutch power in the region and was a source of spices for trade.[5]

Before the Spanish withdrawal from Tidore and Ternate in 1663, the Tidore sultanate, although nominally part of the Spanish East Indies, established itself as one of the strongest and most independent states in the region. After the Spanish withdrawal it continued to resist direct control by the Dutch East India Company (the VOC). Particularly under Sultan Saifuddin (r. 1657–1687), the Tidore court was skilled at using Dutch payment for spices for gifts to strengthen traditional ties with Tidore's traditional peripheral territories. As a result, he was widely respected by many local populations, and had little need to call on foreign military help for governing the kingdom, unlike Ternate which frequently relied upon Dutch military assistance.[6]

Tidore long remained an independent state, albeit with growing Dutch interference, until the late eighteenth century. Like Ternate, Tidore allowed the Dutch spice eradication program (extirpatie) to proceed in its territories.[7] This program, intended to strengthen the Dutch spice monopoly by limiting production to a few places, impoverished Tidore and weakened its control over its periphery.

In 1780 Tidore was forced to sign a treaty that reduced it to a Dutch vassal. The discontented Prince Nuku left Tidore and declared himself Sultan of the Papuan Islands. This was the beginning of a guerilla war which lasted for many years.[8] The Papuans, south-east Halmaherans and east Ceramese sided with the rebellious Prince Nuku. The British sponsored Nuku as part of their campaign against the Dutch in the Moluccas. Captain Thomas Forrest was intimately connected with Nuku and represented the British as ambassador. Nuku could finally take Tidore in 1797 and helped the British to conquer Ternate in 1801.[9] However, his successor Zainal Abidin was expelled by Dutch forces in 1806 and Tidore was firmly brought under colonial rule.[10]

The sultanate was abolished in the Sukarno era and re-established in 1999 with the 36th sultan.[2] Tidore was largely spared from the sectarian conflict of 1999 across the Maluku Islands.[2]

Administration

The island constitutes a municipality (kotamadya) within the province of North Maluku. At the time of the 2010 Census, the municipality covered an area of 1,645.73 square kilometres (635.42 sq mi) and had a Census population of 90,055. However, later in 2010, the mainland part (Oba) became the city of Sofifi, the new provincial capital. This leaves 53,836 as the population covering 127 km2 of land.[11]

The municipality now includes the island of Tidore, together with two small islands (Maitara and Mare), with the loss of the Oba section of Halmahera Island. It was divided into eight districts (kecamatan), of which four constitute the island of Tidore (including the two small islands) and the other four constituted the Oba area on the 'mainland' of Halmahera. These are tabulated below with their areas (in sq km) and their populations at the 2010 Census.[12]

| Name | English name | Area in sq.km | Population Census 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tidore | (Tidore town) | 24.4 | 18,477 |

| Tidore Selatan | South Tidore | 30.1 | 13,129 |

| Tidore Utara | North Tidore | 42.1 | 14,573 |

| Tidore Timur | East Tidore | 30.4 | 7,657 |

| (totals on Tidore Island) | 127.0 | 53,836 | |

| Oba Utara | North Oba | 332.4 | 13,331 |

| Oba Tengah | Central Oba | 620.2 | 7,659 |

| Oba | Oba | 430.7 | 10,337 |

| Oba Selatan | South Oba | 173.7 | 4,892 |

| (totals on Halmahera Island) | 1,557.0 | 36,219 |

Notes

- Kompas

- Witton, Patrick (2003). Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. pp. 827–828. ISBN 1-74059-154-2.

- Azra, Azyumardi (2006). Islam in the Indonesian World: An Account of Institutional Formation. Mizan Pustaka. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-979-433-430-0.

- Leonard Andaya (1993) The world of Maluku. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, p. 99-110.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 169-74.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 190-2.

- Muridan Widjojo (2009) The revolt of Prince Nuku: Cross-cultural alliance-making in Maluku, c. 1780-1810. Leiden: Brill, p. 33-7.

- Muridan widjojo (2009), p. 55-8.

- Muridan Widjojo (2009), p. 75-88.

- Muridan Widjojo (2009), p. 88-94.

- http://sp2010.bps.go.id/files/ebook/8272.pdf

- Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011.

References

- Andaya, Leonard Y. 1993. The world of Maluku: eastern Indonesia in the early modern period. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1490-8.

- Hanna, Willard A. & Des Alwi. 1990. Turbulent times past in Ternate and Tidore. Banda Naira: Rumah Budaya Banda Naira.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Tidore. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tidore. |