Post-classical history

Post-classical history (also called the post-antiquity era, post-ancient era, or pre-modern era) is a periodization commonly used by the school of ‘world history’ instead of Middle or Medieval Ages, which is roughly synonymous.[1] The period runs from about 500 CE to 1500 CE, though there may be regional differences and debates. The era was globally characterized by the expansion of civilizations geographically and development of networks of trade between civilizations.[2][1]

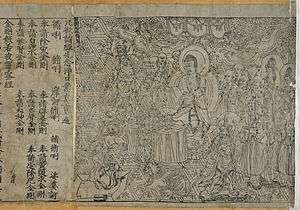

In Asia, the spread of Islam created a new empire and Islamic Golden Age with trade among the Asian, African and European continents, and advances in science in the medieval Islamic world. East Asia experienced the full establishment of power of Imperial China, which established several prosperous dynasties influencing Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Religions such as Buddhism and Neo-Confucianism spread in the region.[3] Gunpowder was developed in China during the post-classical era. The Mongol Empire connected Europe and Asia, creating safe trade and stability between the two regions.[4] In total the population of the world doubled in the time period from approximately 210 million in 500 CE to 461 million in 1500 CE.[5] Population generally grew steadily throughout the period but endured some incidental declines in events including the Plague of Justinian, The Mongol Invasions, Muslim conquests of the Indian subcontinent, and the Black Death.[6]

| Part of a series on | |||

| Human history Human Era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Pleistocene epoch) | |||

| Holocene | |||

|

|

|||

| Ancient | |||

|

|

|||

| Postclassical | |||

|

|

|||

| Modern | |||

|

|||

| ↓ Future | |||

Historiography

Terminology and periodization

‘Post-classical history’ is a periodization used by historians employing a ‘world history’ approach to history, specifically the school developed during the late 20th and the early 21st centuries.[1] Outside of world history, the term is also sometimes used to avoid erroneous pre-conceptions around the terms ‘Middle Ages’, ‘Medieval Ages’ and the ‘Dark Ages’ (see Medievalism), though the application of the term ‘post-classical’ on a global scale is also problematic, and may likewise be Eurocentric.[7]

The post-classical period corresponds roughly to the period from 500 CE to 1450 CE.[1] Beginning and ending dates might vary depending on the region, with the period beginning at the end of the previous classical period: Han China (ending in 220 CE), the Western Roman Empire (in 476 CE), the Gupta Empire (in 543 CE), and the Sasanian Empire (in 651 CE).

The post-classical period is one of the five or six major periods world historians use

- early civilization,

- classical societies,

- post-classical

- early modern,

- long nineteenth century, and

- contemporary or modern era.[1] (Sometimes the nineteenth century and modern are combined.[1])

Although post-classical is synonymous with the Middle Ages of Western Europe, the term post-classical is not necessarily a member of the traditional tripartite periodisation of Western European history into ‘classical’, ‘middle’ and ‘modern’.

Approaches

The historical field of world history, which looks at common themes occurring across multiple cultures and regions, has enjoyed extensive development since the 1980s.[8] However, World History research has tended to focus on early modern globalization (beginning around 1500) and subsequent developments, and views post-classical history as mainly pertaining to Afro-Eurasia.[1] Historians recognize the difficulties of creating a periodization and identifying common themes that include not only this region but also, for example, the Americas, since they had little contact with Afro-Eurasia before the Columbian Exchange.[1] Thus recent research has emphasised that ‘a global history of the period between 500 and 1500 is still wanting’ and that ‘historians have only just begun to embark on a global history of the Middle Ages’.[9]

For many regions of the world, there are well established histories. Although Medieval Studies in Europe tended in the nineteenth century to focus on creating histories for individual nation-states, much twentieth-century research focused, successfully, on creating an integrated history of medieval Europe.[10][11][12][13] The Islamic World likewise has a rich regional historiography, ranging from the fourteenth-century Ibn Khaldun to the twentieth-century Marshall Hodgson and beyond.[14] Correspondingly, research into the network of commercial hubs which enabled goods and ideas to move between China in the East and the Atlantic islands in the West—which can be called the early history of globalization—is fairly advanced; one key historian in this field is Janet Abu-Lughod.[15] Understanding of communication within Sub-Saharan Africa or the Americas is, by contrast, far more limited.[16]

Recent history-writing, therefore, has begun to explore how it might be possible meaningfully to write history that spans the Old World, where human activities were fairly interconnected, and establishes its relationship with other worlds, such as the Americas and Oceania. In the assessment of James Belich, John Darwin, Margret Frenz, and Chris Wickham,

Global history may be boundless, but global historians are not. Global history cannot usefully mean the history of everything, everywhere, all the time. […] Three approaches […] seem to us to have real promise. One is global history as the pursuit of significant historical problems across time, space, and specialism. This can sometimes be characterized as ‘comparative’ history. […] Another is connectedness, including transnational relationships. […] The third approach is the study of globalization […]. Globalization is a term that needs to be rescued from the present, and salvaged for the past. To define it as always encompassing the whole planet is to mistake the current outcome for a very ancient process.[17]

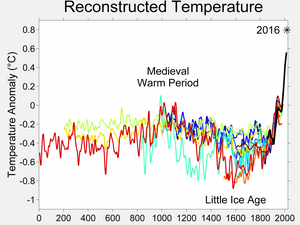

A number of commentators have pointed to the history of the earth's climate as a useful approach to World History in the Middle Ages, noting that certain climate events had effects on all human populations.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

Main trends

The Post-classical era saw several common developments or themes. There was the expansion and growth of civilization into new geographic areas; the rise and/or spread of the three major world, or missionary, religions; and a period of rapidly expanding trade and trade networks.

Growth of civilization

First was the expansion and growth of civilization into new geographic areas across Asia, Africa, Europe, Mesoamerica, and western South America. However, as noted by world historian Peter N. Stearns, there were no common global political trends during the post-classical period, rather it was a period of loosely organized states and other developments, but no common political patterns emerged.[1] In Asia, China continued its historic dynastic cycle and became more complex, improving its bureaucracy. The creation of the Islamic Empires established a new power in the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia. Africa created the Songhai and Mali kingdoms in the West. The fall of Roman civilization not only left a power vacuum for the Mediterranean and Europe, but forced certain areas to build what some historians might call new civilizations entirely.[24] An entirely different political system was applied in Western Europe (i.e. feudalism), as well as a different society (i.e. manorialism). But the once East Roman Empire, Byzantium, retained many features of old Rome, as well as Greek and Persian similarities. Kiev Rus' and subsequently Russia began development in Eastern Europe as well. In the isolated Americas, Mesoamerica saw the building of the Aztec Empire, while the Andean region of South America saw the establishment of the Wari Empire first and the Inca Empire later.

Spread of universal religions

Religion that envisaged the possibility that all humans could be included in a universal order had emerged already in the first millennium BC, particularly with Buddhism. In the following millennium, Buddhism was joined by two other major, universalising, missionary religions, both developing from Judaism: Christianity and Islam. By the end of the period, these three religions were between them widespread, and often politically dominant, across the Old World.[25]

- Buddhism spread from India into China and flourished there briefly before using it as a hub to spread to Japan, Korea, and Vietnam;[26] a similar effect occurred with Confucian revivalism in the later centuries.[25]

- Christianity had become the State church of the Roman Empire in 380, and continued spreading into northern and eastern Europe during the post-classical period at the expense of belief systems that Christians labelled pagan.[27] An attempt was even made to incur upon the Middle East during the Crusades. The split of the Catholic Church in Western Europe and the Orthodox Church in Eastern Europe encouraged religious and cultural diversity in Eurasia.[28]

- Islam began between 610 and 632, with a series of revelations to Muhammad. It helped unify the warring Bedouin clans of the Arabian peninsula and, through a rapid series of Muslim conquests, became established to the west across North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and parts of West Africa, and to the east across Persia, Central Asia, India, and Indonesia.[29]

Trade and communication

Finally, communication and trade across Afro-Eurasia increased rapidly. The Silk Road continued to spread cultures and ideas through trade and throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa. Trade networks were established between West Europe, Byzantium, early Russia, the Islamic Empires, and the Far Eastern civilizations.[30] In Africa the earlier introduction of the Camel allowed for a new and eventually large trans-Saharan trade, which connected Sub-Saharan West Africa to Eurasia. The Islamic Empires adopted many Greek, Roman, and Indian advances and spread them through the Islamic sphere of influence, allowing these developments to reach Europe, North and West Africa, and Central Asia. Islamic sea trade helped connect these areas, including those in the Indian Ocean and in the Mediterranean, replacing Byzantium in the latter region. The Christian Crusades into the Middle East (as well as Muslim Spain and Sicily) brought Islamic science, technology, and goods to Western Europe.[27] Western trade into East Asia was pioneered by Marco Polo. Importantly, China began the sinicization (or Chinese influence) of regions like Japan,[26] Korea, and Vietnam through trade and conquest. Finally, the growth of the Mongol Empire in Central Asia established safe trade such as to allow goods, cultures, ideas, and disease to spread between Asia, Europe, and Africa.

The Americas had their own trade network, however theirs was limited by the lack of draft animals and the wheel. In Oceania some of the island chains of Polynesia and Micronesia also engaged in trade with one another.

Climate

During Post-classical times, there is evidence that many regions of the world were affected similarly by global climate conditions; however, direct effects in temperature and precipitation varied by region. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, changes did not all occur at once. Generally however, studies found that temperatures were relatively warmer in the 11th century, but colder by the early 17th century. The degree of climate change which occurred in all regions across the world is uncertain, as is whether such changes were all part of a global trend.[31] Climate trends seemed to be more recognizable in the Northern than in the Southern Hemisphere.

There are shorter climate periods that could be said roughly to account for large scale climate trends in the Post-classical Period. These include the Late Antique Little Ice Age, the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age. The extreme weather events of 536–537 were likely initiated by the eruption of the Lake llopango caldera in El Salvador. Sulfate emitted into the air initiated global cooling, migrations and crop failures worldwide, possibly intensifying an already cooler time period.[32] Records show that the world's average temperature remained colder for at least a century afterwards.

The Medieval Warm Period from 950–1250 occurred mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, causing warmer summers in many areas; the high temperatures would only be surpassed by the global warming of the 20th/21st centuries. It has been hypothesized that the warmer temperatures allowed the Norse to colonize Greenland, due to ice-free waters. Outside of Europe there is evidence of warming conditions, including higher temperatures in China and major North American droughts which adversely affected numerous cultures.[33]

After 1250, glaciers began to expand in Greenland, affecting its thermohaline circulation, and cooling the entire North Atlantic. In the 14th century, the growing season in Europe became unreliable; meanwhile in China the cultivation of oranges was driven southward by colder temperatures. Especially in Europe, the Little Ice Age had great cultural ramifications.[34] It persisted until the Industrial Revolution, long after the Post-classical Period.[35] Its causes are unclear: possible explanations include sunspots, orbital cycles of the Earth, volcanic activity, ocean circulation, and man-made population decline.[36]

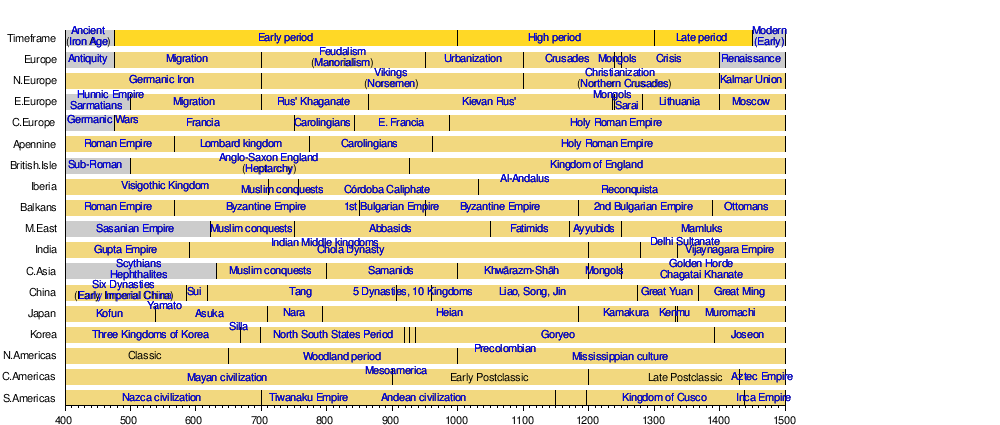

Timeline

This timetable gives a basic overview of states, cultures and events which transpired roughly between the years 400 and 1500. Sections are broken by political and geographic location.[37][38]

- Dates are approximate range (based upon influence), consult particular article for details

- Middle Ages Divisions, Middle Ages Themes

History by region in the Old World

Africa

.jpg)

During the Postclassical Era, Africa was both culturally and politically affected by the introduction of Islam and the Arabic empires.[39] This was especially true in the north, the Sudan region, and the east coast. However, this conversion was not complete nor uniform among different areas, and the low-level classes hardly changed their beliefs at all.[40] Prior to the migration and conquest of Muslims into Africa, much of the continent was dominated by diverse societies of varying sizes and complexities. These were ruled by kings or councils of elders who would control their constituents in a variety of ways. Most of these peoples practiced spiritual, animistic religions. Africa was culturally separated between Saharan Africa (which consisted of North Africa and the Sahara Desert) and Sub-Saharan Africa (everything south of the Sahara). Sub-Saharan Africa was further divided into the Sudan, which covered everything north of Central Africa, including West Africa. The area south of the Sudan was primarily occupied by the Bantu peoples who spoke the Bantu language. From 1100 onward Christian Europe and the Islamic World became dependent on Africa for gold.[41]

After 650 approximately urbanization expanded for the first time beyond the ancient kingdoms Aksum and Nubia. The precolonial African civilizations can be divided into three categories based on religion:

- Christian civilizations on the Horn of Africa,

- Islamic civilizations which formed in the Niger River valley in West Africa, and on the coast of East Africa, and

- traditional societies which adhered to native African religions.[42] South of the Sahara African kingdoms developed based on continental trade with one another through land based routes and generally avoided sea trade.[41]

Sub-Saharan Africa was part of two large, separate trading networks, the Trans Saharan trade which bridged commerce between West and North Africa. Due to the huge profits from trade native African Islamic empires arose, including those of Ghana, Mali and Songhay.[43] In the 14th century, Mansa Musa king of Mali may have been the wealthiest person of his time.[44] Within Mali, the city of Timbuktu was an international center of science and well known throughout the Islamic World, particularly from the University of Sankore. East Africa was part of the Indian Ocean trade network, which included both Arab ruled Islamic cities on the East African Coast such as Mombasa and Traditional cities such as Great Zimbabwe which exported gold, copper and ivory to markets in the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.[45]

Europe

In Europe, Western civilization reconstituted after the Fall of the Western Roman Empire into the period now known as the Early Middle Ages (500–1000). The Early Middle Ages saw a continuation of trends begun in Late Antiquity: depopulation, deurbanization, and increased barbarian invasion.[46]

From the 7th until the 11th centuries Arabs, Magyars and Norse were all threats to the Christian Kingdoms that killed thousands of people over centuries.[47] Raiders however, also created new trading networks.[48] In western Europe the Frankish king Charlemagne attempted to kindle the rise of culture and science in the Carolingian Renaissance.[49] In the year 800 Charlemagne founded the Holy Roman Empire in attempt to resurrect Classical Rome.[50] The reign of Charlemange attempted to kindle a rise of learning and literacy in what has become known as the Carolingian Renaissance[51]

In Eastern Europe, the Eastern Roman Empire survived in what is now called the Byzantine Empire which created the Code of Justinian that inspired the legal structures of modern European states.[52] Ruled by religious Christian Orthodox emperors the Byzantine Eastern Orthodox Church Christianized the Kieven Rus, who were the foundation of modern-day Russia and Ukraine.[53] Byzantium flourished as the leading power and trade center in its region in the Macedonian Renaissance until it was overshadowed by Italian City States and the Islamic Ottoman Empire near the end of the Middle Ages.[54][55]

Later in the period, the creation of the feudal system allowed greater degrees of military and agricultural organization. There was sustained urbanization in northern and western Europe.[56] Later developments were marked by manorialism and feudalism, and evolved into the prosperous High Middle Ages.[56] After 1000 the Christian kingdoms that had emerged from Rome's collapse changed dramatically in their cultural and societal character.[48]

During the High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1300), Christian-oriented art and architecture flourished and the Crusades were mounted to recapture the Holy Land from Muslim control.[57] The influence of the emerging nation-state was tempered by the ideal of an international Christendom and the presence of the Roman Catholic Church in all western kingdoms.[58] The codes of chivalry and courtly love set rules for proper behavior, while the Scholastic philosophers attempted to reconcile faith and reason.[59] The age of Feudalism would be dramatically transformed by the cataclysm of the Black Death and its aftermath.[60] This time would be a major underlying cause for the Renaissance. By the turn of the 16th century European or Western Civilization would be engaging in the Age of Discovery.[61]

The term "Middle Ages" first appears in Latin in the 15th century and reflects the view that this period was a deviation from the path of classical learning, a path supposedly reconnected by Renaissance scholarship.[62]

West Asia

The Arabian peninsula and the surrounding Middle East and Near East regions saw dramatic change during the Postclassical Era caused primarily by the spread of Islam and the establishment of the Arabian Empires.[63]

In the 5th century, the Middle East was separated by empires and their spheres of influence; the two most prominent were the Sasanian Empire of the Persians in what is now Iran and Iraq, and the Byzantine Empire in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). The Byzantines and Sasanians fought with each other continually, a reflection of the rivalry between the Roman Empire and the Persian Empire seen during the previous five hundred years.[64] The fighting weakened both states, leaving the stage open to a new power.[65] Meanwhile, the nomadic Bedouin tribes who dominated the Arabian desert saw a period of tribal stability, greater trade networking and a familiarity with Abrahamic religions or monotheism.

While the Byzantine Roman and Sassanid Persian empires were both weakened by the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, a new power in the form of Islam grew in the Middle East under Muhammad in Medina. In a series of rapid Muslim conquests, the Rashidun army, led by the Caliphs and skilled military commanders such as Khalid ibn al-Walid, swept through most of the Middle East, taking more than half of Byzantine territory in the Arab–Byzantine wars and completely engulfing Persia in the Muslim conquest of Persia. It would be the Arab Caliphates of the Middle Ages that would first unify the entire Middle East as a distinct region and create the dominant ethnic identity that persists today. These Caliphates included the Rashidun Caliphate, Umayyad Caliphate, Abbasid Caliphate, and later the Turkic-based Seljuq Empire.

After Muhammad introduced Islam, it jump-started Middle Eastern culture into an Islamic Golden Age, inspiring achievements in architecture, the revival of old advances in science and technology, and the formation of a distinct way of life.[66] Muslims saved and spread Greek advances in medicine, algebra, geometry, astronomy, anatomy, and ethics that would later finds it way back to Western Europe.

The dominance of the Arabs came to a sudden end in the mid-11th century with the arrival of the Seljuq Turks, migrating south from the Turkic homelands in Central Asia. They conquered Persia, Iraq (capturing Baghdad in 1055), Syria, Palestine, and the Hejaz.[67] This was followed by a series of Christian Western Europe invasions. The fragmentation of the Middle East allowed joint European forces mainly from England, France, and the emerging Holy Roman Empire, to enter the region.[68] In 1099 the knights of the First Crusade captured Jerusalem and founded the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which survived until 1187, when Saladin retook the city. Smaller crusader fiefdoms survived until 1291.[69] In the early 13th century, a new wave of invaders, the armies of the Mongol Empire, swept through the region, sacking Baghdad in the Siege of Baghdad (1258) and advancing as far south as the border of Egypt in what became known as the Mongol conquests.[70] The Mongols eventually retreated in 1335, but the chaos that ensued throughout the empire deposed the Seljuq Turks. In 1401, the region was further plagued by the Turko-Mongol, Timur, and his ferocious raids. By then, another group of Turks had arisen as well, the Ottomans.

South Asia

.jpg)

There has been difficulty applying the word 'medieval' or 'post classical' to the history of South Asia. This section follows historian Stein Burton's definition that corresponds from the 8th century to the 16th century, more of less following the same time frame of the Post Classical Period and the European Middle Ages.[71]

Until the 13th century, there was no less than 20 to 40 different states on the Indian Subcontinent which hosted a variety of cultures, languages, writing systems and religions.[72] In the beginning of the time period Buddhism was predominant throughout the area with the short lived Pala Empire on the Indo Gangetic Plain sponsoring the faith's institutions. One such institution was the Buddhist Nalanda University in modern-day Bihar, India a center of scholarship and brought a divided South Asia onto the global intellectual stage. Another accomplishment was the invention of the Chaturanga game which later was exported to Europe and became Chess.[73] In Southern India, the Hindu Kingdom of Chola gained prominence with an overseas empire that controlled parts of modern-day Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia as oversees territories and helped spread Hinduism into the historic culture of these places.[74] In this time period, neighboring areas such as Afghanistan, Tibet, Southeast Asia were under South Asian influence.[75]

From 1206 onward a series of Turkic Islamic invasions based from modern day Afghanistan and Iran conquered massive portions of Northern India, founding the Delhi Sultanate which remained supreme until the 16th century.[76] The Delhi Sultanate introduced Islam to the conquered populations for the first time. Native religions fared differently, Buddhism declined in South Asia vanishing in many areas but Hinduism survived and reinforced itself in areas conquered by Muslims. In the far South the Kingdom of Vijanyagar was not conquered by any Muslim state in the period. The turn of the 16th century would see the rise of a new Islamic Empire – the Mughals and the establishment of European trade posts by the Portuguese.[77]

Southeast Asia

From the 8th century onward Southeast Asia stood to benefit from the trade taking place between South and East Asia, numerous kingdoms arose in the region due to the flow of wealth passing through the Strait of Malacca. While Southeast Asia had numerous outside influences India was the greatest source of inspiration for the region. North Vietnam as an exception was culturally closer to China for centuries due to conquest.

Since rule from the third century BC North Vietnam continued to be subjugated by Chinese states, although they continually resisted periodically. There were three periods of Chinese Domination that spanned near 1100 years. Vietnam gained long lasting independence in the 10th century when China was divided. Nonetheless, even as an independent state a sort of begrudging sinicization occurred. By the end of the Postclassical Era, Vietnam would be in control of its own Nguyễn dynasty. South Vietnam was governed by the ancient Hindu Champa Kingdom but was annexed by Vietnamese invaders in the 15th century.[78]

The spread of Hinduism, Buddhism and maritime trade between China and South Asia created the foundation for Southeast Asia's first major empires; including the Khmer Empire from Cambodia and Sri Vijaya from Indonesia. During the Khmer Empire's height in the 12th century the city of Angkor Thom was among the largest of the pre-modern world due to its water management. King Jayavarman II constructed over a hundred hospitals throughout his realm.[79] Nearby rose the Pagan Empire in modern-day Burma, using elephants as military might.[80] The construction of the Buddhist Shwezigon Pagoda and its tolerance for believers of older polytheistic gods helped Theravada Buddhism become supreme in the region.[80]

In Indonesia, Srivijaya from the 7th through 14th century was a Thalassocracy that focused on maritime city states and trade. Controlling the vital choke points of the Sunda and Malacca straits it became rich from trade ranging from Japan through Arabia. Gold, Ivory and Ceramics were all major commodities traveling through port cities. The Empire was also responsible for the construction of wonders such as Borobudur. During this time Indonesian sailors crossed the Indian Ocean; evidence suggests that they may have colonized Madagascar.[81] Indian culture spread to the Philippines, likely through Indonesian trade resulting in the first documented use of writing in the archipelago and Indianized kingdoms.[82]

Over time changing economic and political conditions else where and wars weakened the traditional empires of South East Asia. While the Mongol Invasions did not directly annex Southeast Asia the war-time devastation paved way for the rise of new nations. In the 15th century the Khmer Empire was supplanted by the Thai Ayutthaya Kingdom and Sri Vijaya was overtaken by the Majapahit and later the Islamic Malacca Sultanate by 1450.

East Asia

The time frame of 500–1500 in East Asia's history and China in particular has been proposed as an accurate classification for the region's history within the context of global Post-classical history.[84] There has been an attempt made in college courses to adapt the Post-Classical concept to Chinese terms.[85]

During this period the Eastern world empires continued to expand through trade, migration and conquests of neighboring areas. Japan and Korea went under the process of voluntary sinicization, or the impression of Chinese cultural and political ideas.[86][87][88]

Korea and Japan sinicized because their ruling class were largely impressed by China's bureaucracy.[89] The major influences China had on these countries were the spread of Confucianism, the spread of Buddhism, and the establishment of centralized governance.[90] In the times of the Sui, Tang and Song dynasties (581–1279), China remained the world's largest economy and most technologically advanced society.[91][92] Inventions such as gunpowder, woodblock printing and the magnetic compass were improved upon. China stood in contrast to other areas at the time as the imperial governments exhibited concentrated central authority instead of feudalism.[93]

China exhibited much interest in foreign affairs, during the Tang and Song dynasties. From the 7th through the 10th Tang China was focused on securing the Silk Road as the selling of its goods westwards was central to the nation's economy.[94][95] For a time China, successfully secured its frontiers by integrating their nomadic neighbors such as the Gokturks into their civilization.[96] The Tang dynasty expanded into Central Asia and received tribute from Eastern Iran.[97] Western expansion ended with wars with the Umayyad Caliphate and the deadly An Lushan Rebellion which resulted in an deadly but uncertain death toll of millions.[98]

After the collapse of the Tang dynasty and subsequent civil wars came the second phase of Chinese interest in foreign relations. Unlike the Tang, the Song specialized in overseas trade and peacefully created a maritime network and China's population became concentrated in the south.[99] Chinese merchant ships reached Indonesia, India and Arabia. Southeast Asia's economy flourished from trade with Song China.[100]

.jpg)

With the country's emphasis on trade and economic growth, Song China's economy began to use machines to manufacture goods and coal as a source of energy.[101] The advances of the Song in the 11th/12th centuries have been considered an early industrial revolution.[102] Economic advancements came at the cost of military affairs and the Song became open to invasions from the north. China became divided as Song's northern lands were conquered by the Jurchen people.[103] By 1200 there were five Chinese kingdoms stretching from modern day Turkestan to the Sea of Japan including the Western Liao, Western Xia, Jin, Southern Song and Dali.[104] Because these states competed with each other they all were eventually annexed by the rising Mongol Empire before 1279.[105]

After seventy years of conquest, the Mongols proclaimed the Yuan dynasty and also annexed Korea; they failed to conquer Japan.[106] Mongol conquerors also made China accessible to European travelers such as Marco Polo.[107] The Mongol era was short lived due to plagues and famine.[108] After revolution in 1368 the succeeding Ming dynasty ushered in a period of prosperity and brief foreign expeditions before isolating itself from global affairs for centuries.[109]

Korea and Japan however continued to have relations with China and with other Asian countries. In the 15th century Sejong the Great of Korea cemented his country's identity by creating the Hangul Writing system to replace use of Chinese Characters.[110] Meanwhile, Japan fell under military rule of the Kamakura and later Ashikaga Shogunate dominated by Samauri warriors.[111]

Eurasia

This section explains events and trends which affected the geographic area of Eurasia. The civilizations within this area were distinct from one another but still endured shared experiences and some development patterns

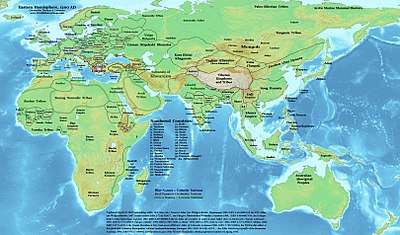

Map of the Eastern Hemisphere 500 AD

Map of the Eastern Hemisphere 500 AD Map of the Eastern Hemisphere 800 AD

Map of the Eastern Hemisphere 800 AD Map of the Eastern Hemisphere 1200 AD.

Map of the Eastern Hemisphere 1200 AD.

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire which existed during the 13th and 14th centuries, was the largest continuous land empire in history.[112] Originating in the steppes of Central Asia, the Mongol Empire eventually stretched from Central Europe to the Sea of Japan, extending northwards into Siberia, eastwards and southwards into the Indian subcontinent, Indochina, and the Iranian plateau, and westwards as far as the Levant and Arabia.[113]

The Mongol Empire emerged from the unification of nomadic tribes in the Mongolia homeland under the leadership of Genghis Khan, who was proclaimed ruler of all Mongols in 1206. The empire grew rapidly under his rule and then under his descendants, who sent invasions in every direction.[114][115][116][117][118][119] The vast transcontinental empire connected the east with the west with an enforced Pax Mongolica allowing trade, technologies, commodities, and ideologies to be disseminated and exchanged across Eurasia.[120][121]

The empire began to split due to wars over succession, as the grandchildren of Genghis Khan disputed whether the royal line should follow from his son and initial heir Ögedei, or one of his other sons such as Tolui, Chagatai, or Jochi. After Möngke Khan died, rival kurultai councils simultaneously elected different successors, the brothers Ariq Böke and Kublai Khan, who then not only fought each other in the Toluid Civil War, but also dealt with challenges from descendants of other sons of Genghis.[122] Kublai successfully took power, but civil war ensued as Kublai sought unsuccessfully to regain control of the Chagatayid and Ögedeid families.

The Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 marked the high-water point of the Mongol conquests and was the first time a Mongol advance had ever been beaten back in direct combat on the battlefield. Though the Mongols launched many more invasions into the Levant, briefly occupying it and raiding as far as Gaza after a decisive victory at the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in 1299, they withdrew due to various geopolitical factors.

By the time of Kublai's death in 1294, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates or empires, each pursuing its own separate interests and objectives: the Golden Horde khanate in the northwest; the Chagatai Khanate in the west; the Ilkhanate in the southwest; and the Yuan dynasty based in modern-day Beijing.[123] In 1304, the three western khanates briefly accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Yuan dynasty,[124][125] but it was later overthrown by the Han Chinese Ming dynasty in 1368.[126] The Genghisid rulers returned to Mongolia homeland and continued rule in the Northern Yuan dynasty.[126] All of the original Mongol Khanates collapsed by 1500, but smaller successor states remained independent until the 1700s. Descendants of Chagatai Khan created the Mughal Empire that ruled much of India in early modern times.[126]

The Silk Road

The Silk Road was a Eurasian trade route that played a large role in global communication and interaction. It stimulated cultural exchange; encouraged the learning of new languages; resulted in the trade of many goods, such as silk, gold, and spices; and also spread religion and disease.[127] It is even claimed by some historians – such as Andre Gunder Frank, William Hardy McNeill, Jerry H. Bentley, and Marshall Hodgson – that the Afro-Eurasian world was loosely united culturally, and that the Silk Road was fundamental to this unity.[127] This major trade route began with the Han dynasty of China, connecting it to the Roman Empire and any regions in between or nearby. At this time, Central Asia exported horses, wool, and jade into China for the latter's silk; the Romans would trade for the Chinese commodity as well, offering wine in return.[128] The Silk Road would often decline and rise again in trade from the Iron Age to the Postclassical Era. Following one such decline, it was reopened in Central Asia by Han Dynasty General Ban Chao during the 1st century.[129]

The Silk Road was also a major factor in spreading religion across Afro-Eurasia. Muslim teachings from Arabia and Persia reached East Asia. Buddhism spread from India, to China, to Central Asia. One significant development in the spread of Buddhism was the carving of the Gandhara School in the cities of ancient Taxila and the Peshwar, allegedly in the mid 1st century.[129]

The route was vulnerable to spreading plague. The Plague of Justinian originated in East Asia and had a major outbreak in Europe in 542 causing the deaths of a quarter of the Mediterranean's population. Trade between Europe, Africa and Asia along the route was at least partially responsible for spreading the plague.[130] There is a popular theory that the Black Death was caused by the Mongol conquests. The claim is that the direct link that it opened between the East and West provided the path for rats and fleas that carried the disease.[131] Although there is no concrete historical evidence to this theory, the plague is considered endemic on the steppe.[132]

There were vulnerabilities as well to changing political situations. The rise of Islam changed the Silk Road, because Muslim rulers generally closed the Silk Road to Christian Europe to an extent Europe would be cut off from Asia for centuries. Specifically, the political developments that affected the Silk Road included the emergence of the Turks, the political movements of the Sasanian and Byzantine empires, and the rise of the Arabs, among others.[133]

The Silk Road flourished again in the 13th century during the reign of the Mongol Empire, which through conquest had brought stability in Central Asia comparable to the Pax Romana.[134] It was claimed by a Muslim historian that Central Asia was peaceful and safe to transverse

"(Central Asia) enjoyed such a peace that a man might have journeyed from the land of sunrise to the land of sunset with a golden platter upon his head without suffering the least violence from anyone."[135]

As such, trade and communication between Europe, East Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East required little effort. Handicraft production, art, and scholarship prospered, and wealthy merchants enjoyed cosmopolitan cities.[135]

The Silk Road trade played a role in spreading the infamous Black Death. Originating in China, the bubonic plague was spread by Mongol warriors catapulting diseased corpses into enemy towns in the Crimea. The disease, spread by rats, was carried by merchant ships sailing across the Mediterranean that brought the plague back to Sicily, causing an epidemic in 1347.[136] Nevertheless, after the 15th century, the Silk Road disappeared from regular use.[134] This was primarily a result from the growing sea travel pioneered by Europeans, which allowed the trade of goods by sailing around the southern tip of Africa and into the Indian Ocean.[134]

Science

The term Post-Classical Science is often used in academic circles and in college courses to combine the study of medieval European science and medieval Islamic science due to their interactions with one another.[137] However Science also spread from Eastern Eurasia, particularly from China was spread westward by Arabs due to both war and trade. The Islamic World also benefited from medical knowledge from South Asia.[138]

In the case of the Western World and in Islamic realms much emphasis was placed on preserving the rationalist Greek Tradition of figures such as Aristotle. In the context of science within Islam there are questions as to whether Islamic Scientists simply preserved accomplishments from Antiquity or built upon earlier Greek advances.[139][140] Regardless, Classical European Science was brought back to the Christian Kingdoms due to the experience of the Crusades.[59]

As a result of Persian trade in China, and the battle of the Talas River, Chinese innovations entered the Islamic intellectual world.[141] These include advances in astronomy and in paper-making.[142][143] Paper-making spread through the Islamic World as far west as Islamic Spain, before paper-making was acquired for Europe by the Reconquista.[144] There is debate about transmission of gunpowder on whether the Mongols introduced Chinese gunpoweder weapons to Europe or if gunpowder weapons were invented in Europe independently.[145][146]

Literate culture and arts

Within Eurasia, there were four major civilization groups that had literate cultures and created literature and arts, including Europe, the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia. Southeast Asia could be a possible fifth category but was influenced heavily from both South and East Asia literal cultures. All four cultures in Post-Classical Times used poetry, drama and prose. Throughout the period and until the 19th century poetry was the dominant form of literary expression. In the Middle East, South Asia, Europe and China great poetic works often used figurative language. Examples include, the Sanskrit Shakuntala, the Arabic Thousand and one nights, Old English Beowulf and works by the Chinese Du Fu. In Japan, prose uniquely thrived more than in other geographic areas. The Tale of Genji is considered the world's first realistic novel written in the 9th century.[147]

Musically, most regions of the world only used melodies as opposed to harmony. Medieval Europe was the lone exception to this rule, developing harmonic music in the 14th/15th century as musical culture transitioned form sacred music (meant for the church) to secular music.[148] South Asian and Mid-Eastern music were similar to each other for their use of microtone. East-Asian music shared some similarities with European Music for using a pentatnotic scale.

The Americas

The Postclassical Era of the Americas can be considered set at a different time span from that of Afro-Eurasia. As the developments of Mesoamerican and Andean civilization differ greatly from that of the Old World, as well as the speed at which it developed, the Postclassical Era in the traditional sense does not take place until near the end of the medieval age in Afro-Eurasia. As such, for the purposes of this article, the Woodland period and Classic stage of the Americas will be discussed here, which takes place from about 400 to 1400.[149] For the technical Postclassical stage in American development which took place on the eve of European contact, see Post-Classic stage.

Cultural areas of North America prior to European Contact

Cultural areas of North America prior to European Contact- Cultural areas of South and Central America prior to European contact, (in Spanish).

North America

As a continent there was little unified trade or communication. Advances in agriculture spread northward from Mesoamerica indirectly through trade. Major cultural areas however still developed independently of each other.

Norse Contact and the Polar Regions

While there was little regular contact between the Americas and the Old World the Norse Vikings explored and even colonized Greenland and Canada as early as 1000. None of these settlements survived past Medieval Times. Outside of Scandinavia knowledge of the discovery of the Americas was interpreted as a remote island or the North Pole.[150]

The Norse arriving from Greenland settled Greenland from approximately 980 to 1450.[151] The Norse arrived in southern Greenland prior to the 13th century approach of Inuit Thule people in the area. The extent of the interaction between the Norse and Thule is unclear.[151] Greenland was valuable to the Norse due to trade of ivory that came from the tusks of walruses. The Little Ice Age adversely affected the colonies and they vanished.[151] Greenland would be lost to Europeans until Danish Colonization in the 18th century.[152]

The Norse also explored and colonized farther south in Newfoundland Canada at L'Anse aux Meadows referred to by the Norse as Vinland. The colony at most existed for twenty years and resulted in no known transmission of diseases or technology to the First Nations. To the Norse Vinland was known for plentiful grape vines to make superior wine. One reason for the colony's failure was constant violence with the native Beothuk tribe who the Norse referred to as Skraeling.

After initial expeditions there is a possibility that the Norse continued to visit modern day Canada. Surviving records from medieval Iceland indicate some sporadic voyages to a land called Markland, possibly the coast of Labrador, Canada, as late as 1347 presumably to collect wood for deforested Greenland.[153]

Northern Areas

In northern North America, many hunter-gatherer and agricultural societies thrived in the diverse region. Native American tribes varied greatly in characteristics; some, including the Mississippian culture and the Ancestral Puebloans were complex chiefdoms. Other nations which inhabited the states of the modern northern United States and Canada had less complexity and did not follow technological changes as quickly. Approximately around the year 500 during the Woodland period, Native Americans began to transition to bows and arrows from spears for hunting and warfare.[154] Technological advancement however was uneven. During the 12th century was the widespread adoption of Corn as a staple crop in the Eastern United States. Corn would continue to be the staple crop of natives in the Eastern United States and Canada until the Colombian Exchange.

In the eastern United States, rivers were the medium of trade and communication. Cahokia located in the modern U.S State of Illinois was among the most significant within the Mississippi Culture. Focused around Monks Mound archaeology indicates the population increased exponentially after 1000 because it manufactured important tools for agriculture and cultural attractions.[155] Around 1350 Cahokia was abandoned, environmental factors have been proposed for the city's decline.[156]

At the same time Ancestral Puebloans constructed clusters of buildings in the Chaco Canyon site located in the State of New Mexico. Individual houses may have been occupied by more than 600 residents at any one time. Chaco Canyon was the only pre-Columbian site in the United States to build paved roads.[157] Pottery indicates a society that was becoming more complex, turkeys for the first time in the continental United States were also domesticated. Around 1150 the structures of Chaco Canyon were abandoned, likely as a result of severe drought.[158][159][160] There were also other Pueblo complexes in the Southwestern United States. After reaching climaxes native complex societies in the United States declined and did not entirely recover before the arrival of European Explorers.[161]

Mesoamerica

At the beginning of the global Post Classic Period, the city of Teotihuacan was at its zenith, housing over 125,000 people, at 500 A.D it was the sixth largest city in the world at the time.[162] The city's residents built the Pyramid of the Sun the third largest pyramid of the world, oriented to follow astronomical events. Suddenly in the 6th and 7th centuries, the city suddenly declined possibly as a result of severe environmental damage caused by extreme weather events of 535–536. There is evidence that large parts of the city were burned, possibly in a domestic rebellion.[163] The city's legacy would inspire all future civilizations in the region.[164]

At the same time was Classic Age of the Mayan Civilization clustered in dozens of city states on the Yucatán and modern day Guatemala.[165] The most significant of these cities were Chichen Itza which often fiercely competed with its neighbors to be the dominant economic influence in the region.

The Mayans had an upper caste of priests, who were well versed in astronomy, mathematics and writing. The Mayan developed the concept of zero, and a 365-day calendar which possibly pre-dates its creation in Old-World societies.[166] After 900, many Mayan cities suddenly declined in a period of drought.

The Toltec Empire arose from the Toltec culture, and were remembered as wise and benevolent leaders. One priest-king called Ce Acatl Topiltzin advocated against human sacrifice.[167] After his death in 947, civil wars of religious character broke out between those who supported and opposed Topiltzin's teachings.[167] Modern historians however are skeptical of the extent of Toltec and influence and believe that much of the information known about the Toltecs was created by the later Aztecs as an inspiration myth.[168]

In the 1300s, a small band of violent, religious radicals called the Aztecs began minor raids throughout the area.[169] Eventually they began to claim connections with the Toltec civilization, and insisted they were the rightful successors.[170] They began to grow in numbers and conquer large areas of land. Fundamental to their conquest, was the use of political terror in the sense that the Aztec leaders and priests would command the human sacrifice of their subjugated people as means of humility and coercion.[169] Most of the Mesoamerican region would eventually fall under the Aztec Empire.[169] On the Yucatán Peninsula most of the Mayan People continued to be independent of the Aztecs but their traditional civilization declined.[171] Aztec developments expanded cultivation, applying the use of chinampas, irrigation, and terrace agriculture; important crops included maize, sweet potatoes, and avocados.[169]

In 1430 the city of Tenochtitlan allied with other powerful Nahuatl speaking cities- Texcoco and Tlacopan to create the Aztec Empire otherwise known as Triple-Alliance.[171] Though referred to as an empire the Aztec Empire functioned as a system of tribute collection with Tenochtitlan at its center. By the turn of the 16th century "flower wars" between the Aztecs and rival states such as Tlaxcala had continued for over fifty years.[172]

South America

South American civilization was concentrated in the Andean region which had already hosted complex cultures since 2,500 BC. East of the Andean region, the natives were generally semi nomadic. Discoveries on the Amazon River Basin indicate the region likely had a pre-contact population of five million people and hosted complex societies.[173] Around the continent numerous agricultural peoples from Colombia to Argentina steadily advanced from 500 AD until European contact.[174]

Andean Region

.jpg)

During Ancient times the Andean Region had developed civilizations independent of outside influences including that of Mesoamerica.[175] Through the Post Classical era a cycle of civilizations continued until Spanish contact. Collectively Andean societies lacked currency, a written language and solid draft animals enjoyed by old world civilizations. Instead Andeans developed other methods to foster their growth, including use of the quipu system to communicate messages, lamas to carry smaller loads and an economy based on reciprocity.[169] Societies were often based on strict social hierarchies and economic redistribution from the ruling class.[169]

In the first half of the Post Classical Period the Andean Region was dominated by two almost equally powerful states. In the North of Peru was the Wari Empire and in the South of Peru and Bolivia there was the Tiwanaku empire both of whom were inspired by the earlier Moche People. While the extent of their relationship to each other is unknown, it is believed that they were in a Cold-War with one another, competing but avoiding direct conflict to avoid mutual assured destruction. Without war there was prosperity and around the year 700 Tiwanaku city hosted a population of 1.4. million.[176] After the 8th century both states declined due to changing environmental conditions, laying the ground work for the Incas to emerge as a distinct culture centuries later.[177]

In the 15th century the Inca Empire rose to annex all other nations in the area. Led by their, sun-god king, Sapa Inca, they slowly conquered what is now Peru, and built their society throughout the Andes cultural region. The Incas spoke the Quechua languages. The Incas used the advances created by earlier Andean societies. Incas have been known to have used abacuses to calculate mathematics. The Inca Empire is known for some of its magnificent structures, such as Machu Picchu in the Cusco region.[178] The empire expanded quickly northwards to Ecuador, Southwards to central Chile. To the north of the Inca Empire remained the independent Tairona and Musica Confederation who practiced agriculture and gold metallurgy.[179][180]

Oceania

Map of the Aboriginal regions in Australia

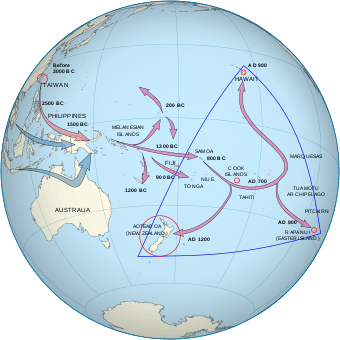

Map of the Aboriginal regions in Australia Colonization of East Polynesia, and dispersal to more remote islands (including Hawaii, Easter Island, and New Zealand)

Colonization of East Polynesia, and dispersal to more remote islands (including Hawaii, Easter Island, and New Zealand)

Separate from developments in Afro-Eurasia and the Americas the region of greater Oceania continued to develop independently of the outside world. In Australia, the society of Aborigines and Melanesia changed little through the Post Classical Period since their arrival in the area from Africa around 50,000 BC. The only outside contact were encounters with fishermen of Indonesian origin.[181] Polynesian and Micronesian Peoples are rooted from Taiwan and Southeast Asia and began their migration into the Pacific Ocean from 3000–1500 BC.[182]

During Post-classical Times the Micronesian and the Polynesian peoples constructed cities in some areas such as Nan Madol and Mu'a. Around 1200 AD the Tu'i Tonga Empire spread its influence far and wide throughout the South Pacific Islands, being described by academics as a maritime chiefdom which used trade networks to keep power centralized around the king's capital. Polynesians on outrigger canoes discovered and colonized some of the last uninhabited islands of earth.[182] Hawaii, New Zealand and Easter Island were among the final places to be reached, settlers discovering pristine lands. Oral Tradition claimed that navigator Ui-te-Rangiora discovered icebergs in the Southern Ocean.[183] In exploring and settling, Polynesian settlers did not strike at random but used their knowledge of wind and water currents to reach their destinations.[184]

.jpg)

On the settled islands some Polynesian groups became distinct from one another. A significant example being the Maori of New Zealand. Other island systems kept in contact with each other, such as Hawaii and the Society Islands. Ecologically, Polynesians had the challenge of sustaining themselves within limited environments. Some settlements caused mass extinctions of some native plant and animal species over time by hunting species such as the Moa and introducing the Polynesian Rat.[182] Easter Island settlers engaged in complete ecological destruction of their habtiat and their population crashed afterwards possibly due to the construction of the Easter Island Statues.[185][186][187] Other colonizing groups adapted to accommodate to the ecology of specific islands such as the Moriori of the Chatham Islands.

Europeans on their voyages visited many Pacific Islands in the 16th and 17th century, but most areas of Oceania were not colonized until after the voyages of British explorer James Cook in the 1780s.[188]

End of the period

As the postclassical era drew to a close in the 15th century, many of the empires established throughout the period were in decline.[189] The Byzantine Empire would soon be overshadowed in the Mediterranean by Italian city states such as Venice and Genoa and the Ottoman Turks.[190] The Byzantines faced repeated attacks from eastern and western powers during the Fourth Crusade, and declined further until the loss of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.[189]

The largest change came in terms of trade and technology. The global significance of the fall of the Byzantines was the disruption of overland routes between Asia and Europe.[191] Traditional dominance of Nomadism in Eurasia declined and the Pax Mongolia which had allowed for interactions between different civilizations was no longer available. China, which had previously engaged in expansion and innovation became isolationist in the 14th century under the Ming and would remain so until the Industrial Revolution.[192] Western Asia and South Asia were conquered by gunpowder empires which successfully utilized advances in military technology but closed the Silk Road.[193]

Europeans – specifically the Kingdom of Portugal and various Italian explorers – intended to replace land travel with sea travel.[194] Originally European exploration merely looked for new routes to reach known destinations.[194] Portuguese Explorer Vasco De Gama traveled to India by sea in 1498 by circumnavigating Africa around the Cape of Good Hope.[195] India and the coast of Africa were already known to Europeans but none had attempted a large trading mission prior to that time.[195] Due to navigation advances Portugal would create a global colonial empire beginning with the conquest of Malacca in modern-day Malaysia from 1511.[196]

Other Explorers such as the Spanish sponsored Italian Christopher Columbus intended to engage in trade by traveling on unfamiliar routes west from Europe. The subsequent European discovery of the Americas in 1492 resulted in the Colombian exchange and the world's first pan-oceanic globalization.[197] Spanish Explorer Ferdinand Magellan performed the first known circumnavigation of Earth in 1521.[198] The transfer of goods and diseases across oceans was unprecedented in creating a more connected world..[199] From developments in navigation and trade modern history began.[197]

See also

- Age of Empires II – A personal computer game using Post-classical history as its setting.

- Ancient history – covers all human history/prehistory preceding the Postclassical Era.

- Classical antiquity – centered in the Mediterranean Basin, the interlocking civilizations of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome

- Early modern period – succeeding global time period.

- Economic history of the world

- History of cartography – Covers history of cartography and includes images of maps from Post-classical times.

- History by period

- Late Antiquity (aka: Dark Ages) – mainland Europe and the Mediterranean Basin, transition from Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages.

- List of largest cities throughout history

References

Citations

- Stearns, Peter N. (2017). "Periodization in World History: Challenges and Opportunities". In R. Charles Weller (ed.). 21st-Century Narratives of World History: Global and Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Palgrave. ISBN 978-3-319-62077-0.

- The Post‐Classical Era Archived 2014-10-31 at the Wayback Machine by Joel Hermansen

- Thompson, John M. (2010-10-19). The Medieval World: An Illustrated Atlas. National Geographic Books. p. 82. ISBN 9781426205330.

- Times Books (Firm), cartographer., Harper Collins atlas of world history, p. 128, ISBN 9780723010258, OCLC 41347894

- Klein Goldewijk, Kees; Beusen, Arthur; Janssen, Peter (2010-03-22). "Long-term dynamic modeling of global population and built-up area in a spatially explicit way: HYDE 3.1". The Holocene. 20 (4): 565–573. Bibcode:2010Holoc..20..565K. doi:10.1177/0959683609356587. ISSN 0959-6836.

- Haub (1995): "The average annual rate of growth was actually lower from 1 A.D. to 1650 than the rate suggested above for the 8000 B.C. to 1 A.D. period. One reason for this abnormally slow growth was the Black Plague. This dreaded scourge was not limited to 14th century Europe. The epidemic may have begun about 542 A.D. in Western Asia, spreading from there. It is believed that half the Byzantine Empire was destroyed in the 6th century, a total of 100 million deaths."

- Catherine Holmes and Naomi Standen, ‘Introduction: Towards a Global Middle Ages’, Past & Present, 238 (November 2018), 1-44 (p. 16).

- Bentley, the Late Jerry H. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of World History. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235810.001.0001. ISBN 9780199235810.

- Michael Borgolte, ‘A Crisis of the Middle Ages? Deconstructing and Constructing European Identities in a Globalized World’, in The Making of Medieval History, ed. by Graham Loud and Martial Staub (York: York Medieval Press, 2017), ISBN 978-1-903153-70-3, pp. 70-84.

- Graham A. Loud and Martial Staub, ‘Some Thoughts on the Making of the Middle Ages’, in The Making of Medieval History, ed. by Graham Loud and Martial Staub (York: York Medieval Press, 2017), ISBN 978-1-903153-70-3, pp. 1-13.

- Patrick Geary, ‘European Ethnicities and European as an Ethnicity: Does Europe Have too Much History?’, in The Making of Medieval History, ed. by Graham Loud and Martial Staub (York: York Medieval Press, 2017), ISBN 978-1-903153-70-3, pp. 57-69.

- Jinty Nelson, ‘Why Reinventing Medieval History is a Good Idea’, in The Making of Medieval History, ed. by Graham Loud and Martial Staub (York: York Medieval Press, 2017), ISBN 978-1-903153-70-3, pp. 17-36.

- Michael Borgolte, 'A Crisis of the Middle Ages? Deconstructing and Constructing European Identities in a Globalized World', in The Making of Medieval History, ed. by Graham Loud and Martial Staub (York: York Medieval Press, 2017), ISBN 978-1-903153-70-3, pp. 70-84.

- Adam J. Silverstein, Islamic History: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 94-107.

- Michael Borgolte, 'A Crisis of the Middle Ages? Deconstructing and Constructing European Identities in a Globalized World', in The Making of Medieval History, ed. by Graham Loud and Martial Staub (York: York Medieval Press, 2017), ISBN 978-1-903153-70-3, pp. 70-84 [81-83].

- Michael Borgolte, 'A Crisis of the Middle Ages? Deconstructing and Constructing European Identities in a Globalized World', in The Making of Medieval History, ed. by Graham Loud and Martial Staub (York: York Medieval Press, 2017), ISBN 978-1-903153-70-3, pp. 70-84 [80-81].

- James Belich, John Darwin, and Chris Wickham, 'Introduction: The Prospect of Global History', in The Prospect of Global History, ed. by James Belich, John Darwin, Margret Frenz, and Chris Wickham (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 3–22 [3] doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198732259.001.0001.

- William S. Atwell, 'Volcanism and Short-Term Climatic Change in East Asian and World History, c. 1200-1699', Journal of World History, 12.1 (Spring 2001), 29-98.

- Richard W. Bulliet, Cotton, Climate, and Camels in Early Islamic Iran: A Moment in World History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), ISBN 978-0-231-51987-8.

- Ronnie Ellenblum, The Collapse of the Eastern Mediterranean: Climate Change and the Decline of the East, 950-1072 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- John L. Brooke, Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), ISBN 978-1-139-05081-4, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139050814.

- Victor Lieberman, ‘Charter State Collapse in Southeast Asia, c.1250–1400, as a Problem in Regional and World History’, American Historical Review, cxvi (2011), 937–63.

- Bruce M. S. Campbell, The Great Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late-Medieval World (Cambridge, 2016).

- Birken 1992, pp. 451–461.

- Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, trans. by Yuval Noah Harari, John Purcell and Haim Watzman (London: Harvill Secker, 2014), ISBN 978-1-84655-823-8, 978-1-84655-824-5, chapter 12.

- Bowman 2000, pp. 162–167.

- Thompson et al. 2009, p. 288.

- Fletcher, Richard (1997). The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity, 371-1386 AD. London: HarperCollins.

- Silverstein, Adam J. (2010). Islamic History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 9–35. ISBN 978-0-19-954572-8.

- "Environment and Trade: The Viking Age". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 2018-06-27.

- Ahmed, Moinuddin; Anchukaitis, Kevin J.; Asrat, Asfawossen; Borgaonkar, Hemant P.; Braida, Martina; Buckley, Brendan M.; Büntgen, Ulf; Chase, Brian M.; Christie, Duncan A.; Cook, Edward R.; Curran, Mark A.J.; Diaz, Henry F.; Esper, Jan; Fan, Ze-Xin; Gaire, Narayan P.; Ge, Quansheng; Gergis, Joëlle; González-Rouco, J. Fidel; Goosse, Hugues; Grab, Stefan W.; Graham, Nicholas; Graham, Rochelle; Grosjean, Martin; Hanhijärvi, Sami T.; Kaufman, Darrell S.; Kiefer, Thorsten; Kimura, Katsuhiko; Korhola, Atte A.; Krusic, Paul J.; et al. (2013-04-21). "Continental-scale temperature variability during the past two millennia" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 6 (5): 339. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..339P. doi:10.1038/NGEO1797.

- "Old trees reveal Late Antique Little Ice Age (LALIA) around 1,500 years ago". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- "Drought Congruence 1000-1300, Central United States". North American Drought Atlas. 2010.

- "Timeline Middle Ages and Early Modern Period – Environmental History Resources". Environmental History Resources. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- Hendy, E.; Gagan, M.; Alibert, C.; McCulloch, M.; Lough, J.; Isdale, P. (2002). "Abrupt decrease in tropical Pacific sea surface salinity at end of Little Ice Age". Science. 295 (5559): 1511–1514. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.1511H. doi:10.1126/science.1067693. PMID 11859191.

- "Carnegie Department of Global Ecology". dge.carnegiescience.edu. Retrieved 2018-08-03.

- Times Books (Firm), cartographer., Harper Collins atlas of world history, p. 17–19, ISBN 9780723010258, OCLC 41347894

- "TIMELINE: World History". www.wdl.org. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- Stearns et al. 2011, p. 184.

- "Trade and the Spread of Islam in Africa". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- Barraclough, Geoffrey, ed. (2003). Collins Atlas of World History. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Borders Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-681-50288-8.

- "History of Sub-Saharan Africa | Essential Humanities". www.essential-humanities.net. Retrieved 2018-06-09.

- Chronicle of world history. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. 2008. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-56852-680-5. OCLC 298782520.

- Tschanz, David. "Lion of Mali: The Hajj of Mansa Musa". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - HarperCollins atlas of world history, Barraclough, Geoffrey, 1908-1984., Stone, Norman., HarperCollins (Firm), Borders Press in association with HarperCollins, 2003, p. 136, ISBN 978-0-681-50288-8, OCLC 56350180CS1 maint: others (link)

- Gilian Clark, Late Antiquity: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford 2011), pp. 1–2.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; Williams, Nadejda (2016-09-30). World History Cultures, States and Society to 1500. Dahlonega, GA: University of North Georgia, Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; Williams, Nadejda (2016-09-30). World History Cultures, States and Society to 1500. Dahlonega, GA: University of North Georgia, Press. p. 429. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George L.; Miller, Charlotte (2016-09-30). World history : cultures, states, and societies to 1500. Berger, Eugene., Israel, George L., Miller, Charlotte., Parkinson, Brian (Brian R.), Reeves, Andrew., Williams, Nadejda. Dahlonega, GA. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6. OCLC 961216293.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George L.; Miller, Charlotte (2016-09-30). World history : cultures, states, and societies to 1500. Berger, Eugene., Israel, George L., Miller, Charlotte., Parkinson, Brian (Brian R.), Reeves, Andrew., Williams, Nadejda. Dahlonega, GA. pp. 282–283. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6. OCLC 961216293.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; Williams, Nadejda (2016-09-30). World History Cultures, States and Society to 1500. Dahlonega, GA: University of North Georgia, Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George L.; Miller, Charlotte (2016-09-30). World history : cultures, states, and societies to 1500. Berger, Eugene., Israel, George L., Miller, Charlotte., Parkinson, Brian (Brian R.), Reeves, Andrew., Williams, Nadejda. Dahlonega, GA. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6. OCLC 961216293.

- Vidal-Nanquet, Pierre (1987). The Harper Atlas of World History. Harper & Row Publishers. p. 96.

- Vidal-Nanquet, Pierre (1987). The Harper Atlas of World History. Harper & Row Publishers. p. 108.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; Williams, Nadejda (2016). World History Cultures, States and Society to 1500. Dahlonega, GA: University of North Georgia, Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George L.; Miller, Charlotte (2016-09-30). World history : cultures, states, and societies to 1500. Berger, Eugene., Israel, George L., Miller, Charlotte., Parkinson, Brian (Brian R.), Reeves, Andrew., Williams, Nadejda. Dahlonega, GA. p. 433. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6. OCLC 961216293.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George L.; Miller, Charlotte (2016-09-30). World history : cultures, states, and societies to 1500. Berger, Eugene., Israel, George L., Miller, Charlotte., Parkinson, Brian (Brian R.), Reeves, Andrew., Williams, Nadejda. Dahlonega, GA. p. 444. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6. OCLC 961216293.

- Barraclough, Geoffrey, ed. (2003). Collins Atlas of World History. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Borders Press. pp. 122, 123. ISBN 978-0-681-50288-8.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George L.; Miller, Charlotte (2016-09-30). World history : cultures, states, and societies to 1500. Berger, Eugene., Israel, George L., Miller, Charlotte., Parkinson, Brian (Brian R.), Reeves, Andrew., Williams, Nadejda. Dahlonega, GA. p. 451. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6. OCLC 961216293.

- HarperCollins atlas of world history, Barraclough, Geoffrey, 1908-1984., Stone, Norman., HarperCollins (Firm), Borders Press in association with HarperCollins, 2003, p. 142, ISBN 978-0-681-50288-8, OCLC 56350180CS1 maint: others (link)

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George L.; Miller, Charlotte (2016-09-30). World history : cultures, states, and societies to 1500. Berger, Eugene., Israel, George L., Miller, Charlotte., Parkinson, Brian (Brian R.), Reeves, Andrew., Williams, Nadejda. Dahlonega, GA. p. 477. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6. OCLC 961216293.

- Miglio "Curial Humanism" Interpretations of Renaissance Humanism p. 112

- Times Books (Firm), cartographer., Harper Collins atlas of world history, p. 78, ISBN 9780723010258, OCLC 41347894

- Vidal-Nanquet, Pierre (1987). The Harper Atlas of World History. Harper & Row Publishers. p. 70.

- Wells, H.G (1920). The Outline of History. Garden City, NUY: Garden City Publishing Inc. p. 544.

- Vidal-Nanquet, Pierre (1987). The Harper Atlas of World History. Harper & Row Publishers. p. 76.

- Vidal-Nanquet, Pierre (1987). The Harper Atlas of World History. Harper & Row Publishers. p. 110.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; Williams, Nadejda (2016-09-30). World History Cultures, States and Society to 1500. Dahlonega, GA: University of North Georgia, Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; Williams, Nadejda (2016-09-30). World History Cultures, States and Society to 1500. Dahlonega, GA: University of North Georgia, Press. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; Williams, Nadejda (2016-09-30). World History Cultures, States and Society to 1500. Dahlonega, GA: University of North Georgia, Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6.

- Stein, Burton (27 April 2010), Arnold, D. (ed.), A History of India (2nd ed.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, p. 105, ISBN 978-1-4051-9509-6

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Grove Press. pp. xx–xxi.

- Murray, H.J.R. (1913). A History of Chess. Benjamin Press (originally published by Oxford University Press). ISBN 978-0-936317-01-4. OCLC 13472872.

- History of Asia by B.V. Rao p.211

- "The spread of Hinduism in Southeast Asia and the Pacific". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George L.; Miller, Charlotte (2016-09-30). World history : cultures, states, and societies to 1500. Berger, Eugene., Israel, George L., Miller, Charlotte., Parkinson, Brian (Brian R.), Reeves, Andrew., Williams, Nadejda. Dahlonega, GA. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6. OCLC 961216293.

- "mughal_index". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- Kiernan, Ben (2009). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-300-14425-3. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- Cœdès, George (1968). The Indianized states of Southeast Asia. Honolulu: East-West Center Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1. OCLC 961876784.

- Chronicle of world history. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. 2008. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-56852-680-5. OCLC 298782520.

- "Madagascar Founded By Women". Discovery.com. Retrieved 2012-03-23.

- The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History by Richard Bulliet, Pamela Crossley, Daniel Headrick, Steven Hirsch, Lyman Johnson p.186

- Chinese Imperial Dynasties, retrieved 2018-06-26

- Clark, Paul. "Chinese History in the Post-Classical Age (500 CE to 1500 CE)" (PDF). Humanities Institute.

- "A.P World Civilizations China" (PDF). Berkeley.edu. University of California, Berkeley.

- "Ancient Japan". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- "Ancient Japanese & Chinese Relations". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- "Ancient Korean & Chinese Relations". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- HarperCollins atlas of world history, Barraclough,Geoffrey, p. 126CS1 maint: others (link)

- HarperCollins atlas of world history, Barraclough, Geoffrey, 1908-1984., Stone, Norman., HarperCollins (Firm), Borders Press in association with HarperCollins, 2003, p. 181, ISBN 978-0-681-50288-8, OCLC 56350180CS1 maint: others (link)

- Bulliet & Crossley & Headrick & Hirsch & Johnson 2014, p. 264.

- Lockard, Craig (1999). "Tang Civilization and the Chinese Centuries" (PDF). Encarta Historical Essays.

- Dalby, Michael T. (1979), "Court politics in late T'ang times", The Cambridge History of China, Cambridge University Press, pp. 561–681, doi:10.1017/chol9780521214469.010, ISBN 978-1-139-05594-9

- HarperCollins atlas of world history, Barraclough, Geoffrey, p. 126CS1 maint: others (link)

- Chronicle of world history. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. 2008. p. 615. ISBN 978-1-56852-680-5. OCLC 298782520.

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; Williams, Nadejda (2016-09-30). World History Cultures, States and Society to 1500. Dahlonega, GA: University of North Georgia, Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6.

- HarperCollins atlas of world history, Barraclough, Geoffrey, p. 126CS1 maint: others (link)

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; Williams, Nadejda (2016). World History Cultures, States and Society to 1500. Dahlonega, GA: University of North Georgia, Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6.

- HarperCollins atlas of world history, Barraclough, Geoffrey, 1908-1984., Stone, Norman., HarperCollins (Firm), Borders Press in association with HarperCollins, 2003, pp. 126–127, ISBN 978-0-681-50288-8, OCLC 56350180CS1 maint: others (link)

- HarperCollins atlas of world history, Barraclough, Geoffrey, 1908-1984., Stone, Norman., HarperCollins (Firm), Borders Press in association with HarperCollins, 2003, p. 132, ISBN 978-0-681-50288-8, OCLC 56350180CS1 maint: others (link)

- Berger, Eugene; Israel, George L.; Miller, Charlotte (2016). World history : cultures, states, and societies to 1500. Berger, Eugene., Israel, George L., Miller, Charlotte., Parkinson, Brian (Brian R.), Reeves, Andrew., Williams, Nadejda. Dahlonega, GA. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-940771-10-6. OCLC 961216293.

- Patterson, F.So L.; Schafer, J.F. (1978). "Registration of Clintland 60 and Clintland 64 Oats (Reg. No. 280 and 281)". Crop Science. 18 (2): 354. doi:10.2135/cropsci1978.0011183x001800020049x. ISSN 0011-183X.

- Chronicle of world history. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. 2008. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-56852-680-5. OCLC 298782520.

- 國家地震局地球物理硏究所 (China) (1990), 中國歷史地震圖集 : 清時期, Zhongguo di tu chu ban she, ISBN 7503105747, OCLC 26030569

- Chronicleof world history. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. 2008. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-1-56852-680-5. OCLC 298782520.

- HarperCollins atlas of world history, Barraclough, Geoffrey, 1908-1984., Stone, Norman., HarperCollins (Firm), Borders Press in association with HarperCollins, 2003, pp. 128–129, ISBN 978-0-681-50288-8, OCLC 56350180CS1 maint: others (link)

- "The Mongols in World History" (PDF). Asian Topics in World History – via Columbia University.

- "HISTORY OF CHINA". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- "Zheng He". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- Burzillo, David (May 2004). "Writing and World History". World History Connected. 1 (2).

- Chronicle of world history. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. 2008. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-56852-680-5. OCLC 298782520.

- Morgan. The Mongols. p. 5.

- Chronicle of world history. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. 2008. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-56852-680-5. OCLC 298782520.

- Diamond. Guns, Germs, and Steel. p. 367.

- The Mongols and Russia, by George Vernadsky

- The Mongol World Empire, 1206–1370, by John Andrew Boyle

- The History of China, by David Curtis Wright. p. 84.

- The Early Civilization of China, by Yong Yap Cotterell, Arthur Cotterell. p. 223.

- Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281 by Reuven Amitai-Preiss

- Guzman, Gregory G. (1988). "Were the barbarians a negative or positive factor in ancient and medieval history?". The Historian. 50 (4): 568–570. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1988.tb00759.x. JSTOR 24447158.

- Thomas T. Allsen. Culture and Conquest. p. 211.

- Biran, Michael (1997). Qaidu and the Rise of the Independent Mongol State in Central Asia. The Curzon Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-0631-0.

- The Cambridge History of China: Alien Regimes and Border States. p. 413.