Spanish protectorate in Morocco

The Spanish protectorate in Morocco[lower-alpha 1] was established on 27 November 1912 by a treaty between France and Spain[1] that converted the Spanish sphere of influence in Morocco into a formal protectorate.

Spanish protectorate in Morocco Protectorado español en Marruecos الحماية الإسبانية على المغرب | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912–1956 | |||||||||

.svg.png) Coat of arms

| |||||||||

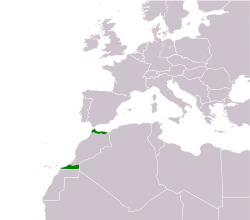

Map of Spanish Morocco with its Northern (Spanish Morocco proper) and Southern (Cape Juby) zones | |||||||||

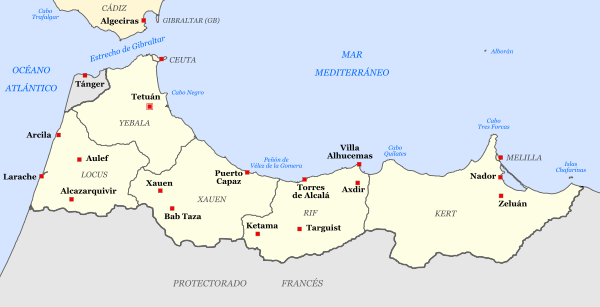

Map of the northern zone in 1956 | |||||||||

| Status | Protectorate of Spain | ||||||||

| Capital | Tetuán | ||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish Berber Arabic Tetuani Ladino or Haketia | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic Judaism Islam | ||||||||

| High Commissioner | |||||||||

• 1913 (first) | Felipe Alfau Mendoza | ||||||||

• 1951–1956 (last) | Rafael García Valiño | ||||||||

| Historical era | 20th Century | ||||||||

• Treaty with France | 27 November 1912 | ||||||||

• Reunited to Morocco | 7 April 1956 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 20,948 km2 (8,088 sq mi) | |||||||||

| Currency | Spanish peseta | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Spanish protectorate consisted of a northern strip on the Mediterranean and the Strait of Gibraltar, and a southern part of the protectorate[2] around Cape Juby, bordering the Spanish Sahara. The northern zone became part of independent Morocco on 7 April 1956, shortly after France had ceded its protectorate (French Morocco). Spain finally ceded its southern zone through the Treaty of Angra de Cintra on 1 April 1958, after the short Ifni War.[3] The city of Tangiers was excluded from the Spanish protectorate and received a special internationally-controlled status as Tangier International Zone.

Since France already held a protectorate over the entire country and controlled Morocco's foreign affairs (since 30 March 1912), it also held the power to delegate a zone to Spanish protection.[4] The surface area of the zone was about 20,948 km2 (8,088 sq mi), which represents 4.69% of modern-day Morocco.

History

Background

At a time when most European nations were stepping up the acquisition of vast colonial empires, Spain was losing the last remnants of hers. Yet within a few years after the disastrous war of 1898, which had forced Spaniards to acknowledge their secondary status among European military powers, their government found it necessary to show an active interest in expansion in northern Morocco. That country, if only because of its geographical position and the presence of the presidios of Ceuta, and Melilla, could not be ignored by the Spaniards despite their lack of enthusiasm for new colonial enterprises. During the last decades of the 19th century, Spain observed with apprehension the increasing interference of Britain and France in the region. The most coherently expressed reason for intervention was fear for the strategic security of Spain. Among others, the Liberal leader Montero Ríos stated that if northwestern Morocco were to come under the civil or military protectorate of France, Spain would see itself besieged perpetually in the north and south by the same power. Furthermore, recent finds of iron ore near Melilla convinced many that Morocco contained vast mineral wealth.[5]

The key motivation for intervention, although less openly stated, was the belief that Morocco was Spain’s last chance to maintain its position in the Concert of Europe, as it was the one area in which it could claim sufficient interest to generate some diplomatic strength with respect to the European powers. There was also the widespread belief, in Spain as elsewhere in Europe at the turn of the 20th century, that the possession of colonies increased the prestige of a nation. Such beliefs made Spanish politicians more receptive to the adoption of a forward policy in Morocco.[6]

Formation

In a convention dated 27 June 1900, France and Spain agreed to recognize separate zones of influence in Morocco, but did not specify their boundaries. In 1902, France offered Spain all of Morocco north of the Sebou River and south of the Sous River, but Spain declined in the belief that such a division would offend Britain.[7] The British and French, without any Spanish insistence, declared Spain's right to a zone of influence in Morocco in Article 8 of the Entente cordiale of 8 April 1904:[7]

The two Governments, inspired by their feeling of sincere friendship for Spain, take into special consideration the interests which that country derives from her geographical position and from her territorial possessions on the Moorish coast of the Mediterranean. In regard to these interests the French Government will come to an understanding with the Spanish Government. The agreement which may be come to on the subject between France and Spain shall be communicated to His Britannic Majesty's Government.

What exactly "special consideration" meant was dealt with in the secret third and fourth articles, specifying that Spain would be required to recognise Articles 4 and 7 of the treaty but could decline the "special consideration" if she wished:

The two Governments agree that a certain extent of Moorish territory adjacent to Melilla, Ceuta, and other presides should, whenever the Sultan ceases to exercise authority over it, come within the sphere of influence of Spain, and that the administration of the coast from Melilla as far as, but not including, the heights on the right bank of the Sebou shall be entrusted to Spain.

The British goal in these negotiations with France was to ensure that a weaker power (Spain) held the strategic coast opposite Gibraltar in return for Britain ceding all interest in Morocco.[7] France began negotiating with Spain at once, but the offer of 1902 was no longer on the table. Since France had given up her ambitions in Ottoman Libya in a convention with Italy in 1903, she felt entitled to a greater share of Morocco. On 3 October 1904, France and Spain concluded a treaty that defined their precise zones.[8] Spain received a zone of influence consisting of a northern strip of territory and a southern strip. The northern strip did not reach to the border of French Algeria, nor did it include Tangier, soon to be internationalized. The southern strip represented the southernmost part of Morocco as recognized by the European powers: the territory to its south, Saguia el-Hamra, was recognized by France as an exclusively Spanish zone. The treaty also recognized the Spanish enclave of Ifni and delimited its borders.[9]

In March 1905, the German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, visited Tangier, a city of international character in northern Morocco. There he loudly touted Germany's economic interests in Morocco and assured the Sultan of financial assistance in the event of a threat to Moroccan independence. At Wilhelm's urging, Sultan Abd el Aziz called for an international conference. The final act of the Algeciras Conference (7 April 1906) created the State Bank of Morocco, guaranteed the attending powers equal commercial rights in Morocco and created a native Moroccan police force led by French and Spanish officers.[10]

The final Spanish zone of influence consisted of a northern strip and a southern strip centred on Cape Juby. The consideration of the southern strip as part of the protectorate back in 1912 eventually gave Morocco a solid legal claim to the territory in the 1950s.[2] While the sparsely populated Cape Juby was administered as a single entity with Spanish Sahara, the northern territories were administered, separately, as a Spanish protectorate with its capital at Tetuán.

The Protectorate system was established in 1912. The Islamic legal system of qadis was formally maintained.

Rif War

Following the First World War, the Republic of the Rif, led by the guerrilla leader Abd el-Krim, was a breakaway state that existed from 1921 to 1926 in the Rif region, when it was subdued and dissolved by joint expedition of the Spanish Army of Africa and French forces during the Rif War.

The Spanish lost more than 13,000 soldiers at Annual in July–August 1921. Controversy in Spain over the early conduct in the war was a driving factor behind the military coup by General The 2nd Marqués de Estella in 1923 which foreshadowed the Spanish Civil War of 1936–39.[11]

After the successful 1925 Alhucemas landing, the French–Spanish alliance ended up achieving victory and putting an end to the war.

Second Spanish Republic

Before 1934, the southern part of the protectorate (Tekna)[12] was governed from Cape Juby (within the same southern strip) since 1912; Cape Juby was also head of the Spanish West Africa. Then, in 1934, the southern part began to being managed directly from Tetuán (in the northern part of the protectorate) and the seat of the Spanish West Africa was moved from Cape Juby to the territory of Ifni (not a part of the protectorate), which had been occupied by the Spaniards that year.[12]

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War started in 1936 with the partially successful coup against the Republican Government, which began in Spanish Morocco by an uprising of the Spanish Army of Africa stationed there, although within a day uprisings in Spain itself broke out. This force, which included a considerable number of Moroccan troops (regulares), was under the command of Francisco Franco (who spent much time in Morocco) and became the core of the Spanish Nationalist Army. The Communist Party of Spain and Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), advocated anti-colonial policies, and pressured the Republican government to support the independence of Spanish Morocco, intending to create a rebellion at Franco's back and cause disaffection among his Moroccan troops. The government — then led by the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) — rejected that course of action as it would have likely resulted in conflict with France, the colonial ruler of the other portion of Morocco.[13]

Because the locally recruited Muslim regulares had been among Franco's most effective troops, the protectorate enjoyed more political freedom and autonomy than Francoist Spain-proper after Franco's victory.[14] The area held competing political parties and a Moroccan nationalist press, which often criticized the Spanish government.

World War II

Spanish troops provisionally occupied Tangier during World War II, on the pretext that an Italian invasion was imminent.[15]

Retrocession to Morocco

In 1956, when France ended its protectorate over Morocco, Spain discontinued the protectorate and retroceded the territory to the newly independent kingdom, while retaining the plazas de soberanía which were part of Spain prior to the colonial period, Cape Juby, Ifni, and other colonies (such as Spanish Sahara) outside of Morocco. Unwilling to accept this, the Moroccan Army of Liberation waged war against the Spanish forces. In the 1958 Ifni War, which spread from Sidi Ifni to Río de Oro, Morocco gained Tarfaya (the southern part of the protectorate) and reduced the Spanish control of the Ifni territory to the perimeter of the city itself. In 1969, through negotiation, Morocco obtained Ifni as well.

As of 2020, Morocco still claims Ceuta and Melilla as integral parts of the country, and considers them to be under foreign occupation, comparing their status to that of Gibraltar. Spain considers both cities integral parts of the Spanish geography, since they were part of Spain for centuries before the occupation of Morocco.

Economy

Mines

The iron mines in the Rif were one of the sources of income. Their exploitation led to an economic boom in Melilla.

Transport

After the Treaty of Algeciras signed in April 1906, where the northern part of Morocco was placed under Spanish administration, the Spanish started to develop this mineral-rich area, and numerous narrow gauge railways were built.

See also

Notes

- Arabic: حماية إسبانيا في المغرب Ḥimāyat Isbāniyā fi-l-Mağrib; Spanish: Protectorado español de Marruecos, Spanish pronunciation: [pɾo.tek̚.to.ˈɾa.ðo ɛs.pa.ˈɲol ðɛ ma.ˈrwe.kos] (

References

- "Treaty Between France and Spain Regarding Morocco". The American Journal of International Law. 7 (2 [Supplement: Official Documents]): 81–99. 1913. doi:10.2307/2212275. JSTOR 2212275.

- Vilar 2005, p. 143.

- Gangas Geisse & Santis Arenas 2011, p. 3.

- Woolman 1968, pp. 14–16.

- James A. Chandler, Spain and Her Moroccan Protectorate 1898–1927, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 10, No. 2 (April 1975), p 301–302.

- James A. Chandler, p. 302.

- Woolman 1968, p. 7–8.

- "Treaty Between France and Spain Concerning Morocco". The American Journal of International Law. 6 (2 [Supplement: Official Documents]): 116–20. 1912. doi:10.2307/2212123. JSTOR 2212123.

- Merry del Val 1920a, pp. 330–31.

- Woolman 1968, p. 10–11.

- Porch, Douglas; Spain's African Nightmare; MHQ: Quarterly Journal of Military History; (2006); 18#2; pp. 28–37.

- Vilar 2005, p. 145.

- Tres años de lucha, José Díaz; p. 343; cited in Spain! The Unfinished Revolution; by Landis, Arthur H; 1st ed.; New York: International Publishers; 1975; pp. 189-92; retrieved 2015

- Marin Miguel (1973). El Colonialismo español en Marruecos. Spain: Ruedo Iberico p. 24-26

- Pennell 2001.

Sources

- Gangas Geisse, Mónica; Santis Arenas, Hernán (2011). "El conflicto del Sáhara Occidental" (PDF). Nadir: Revista Electrónica de Geografía Austral. 3 (1): 1–15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merry del Val, Alfonso (1920a). "The Spanish Zones in Morocco". The Geographical Journal. 55 (5): 329–49. doi:10.2307/1780445. JSTOR 1780445.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merry del Val, Alfonso (1920b). "The Spanish Zones in Morocco (Continued)". The Geographical Journal. 55 (6): 409–19. doi:10.2307/1780966. JSTOR 1780966.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nadal, Francesc; Urteaga, Luis; Muro Morales, José Ignacio (2000). "El mapa topográfico del Protectorado de Marruecos en su contexto político e institucional (1923–1940)" (PDF). Documents d'Anàlisi Geogràfica. 36: 15–46.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pélissier, René (1965). "Spain's Discreet Decolonization". Foreign Affairs. 43 (3): 519–27. doi:10.2307/20039116. JSTOR 20039116.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pennell, C. R. (2001). Morocco since 1830: A History. London: Hurst.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vilar, Juan B. (2005). "Franquismo y descolonización española en África". Historia Contemporánea. Bilbao: University of the Basque Country. 30: 129–158. ISSN 1130-2402.

- Woolman, David S. (1968). Rebels in the Rif: Abd el Krim and the Rif Rebellion. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Calderwood, Eric. 2018. Colonial al-Andalus: Spain and the making of modern Moroccan culture. Harvard University Press

- "Min Khalifa Marrakesh Ila Mu’tamar Maghreb El Arabi." (From the caliph of the king of Morocco to the Conference of the Maghreb). (1947, April). El Ahram.

- Wolf, Jean (1994). Les Secrets du Maroc Espagnol: L’epopee D’Abdelkhalaq Torres. Morocco: Balland Publishing Company

- Ben Brahim, Mohammed (1949). Ilayka Ya Ni Ma Sadiq (To you my dear friend). Tetuan, Morocco: Hassania Publishing Company

- Benumaya, Gil (1940). El Jalifa en Tanger. Madrid: Instituto Jalifiano de Tetuan

- Villanova, José-Luis (2010). Cartographie et contrôle au Maroc sous le protectorat espagnol (1912-1956). MappeMonde vol.98