History of Ghana

The Republic of Ghana is named after the medieval West African Ghana Empire.[1] The empire became known in Europe and Arabia as the Ghana Empire after the title of its Emperor, the Ghana. The Empire appears to have broken up following the 1076 conquest by the Almoravid[2] General Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar. A reduced kingdom continued to exist after Almoravid rule ended, and the kingdom was later incorporated into subsequent Sahelian empires, such as the Mali Empire several centuries later. Geographically, the ancient Ghana Empire was approximately 500 miles (800 km) north and west of the modern state of Ghana, and controlled territories in the area of the Sénégal River and east towards the Niger rivers, in modern Senegal, Mauritania and Mali.[3].

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Ghana |

| Timeline |

|

|

Central Sub-Saharan Africa, agricultural expansion marked the period before 500 AD. Farming began earliest on the southern tips of the Sahara, eventually giving rise to village settlements. Toward the end of the classical era, larger regional kingdoms had formed in West Africa, one of which was the Kingdom of Ghana, north of what is today the nation of Ghana. Before its fall at the beginning of the 10th century Akans migrated southward and founded several nation-states around their matriclans, including the first empire of Bono State founded in the 11th century and for which the Brong-Ahafo (Bono Ahafo) region is named. Later Akan ethnic groups such as the Ashanti empire-kingdom, Akwamu, Akyem, Fante state and others are thought to possibly have roots in the original Bono State settlement at Bono Manso.[4] The Ashanti kingdom's government operated first as a loose network and eventually as a centralized empire-kingdom with an advanced, highly specialized bureaucracy centred on the capital Kumasi.

Precolonial period

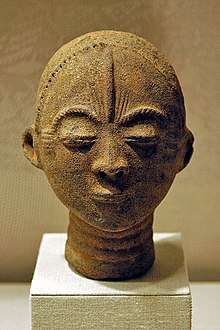

By the end of the 16th century, most of the ethnic groups constituting the modern Ghanaian population had settled in their present locations. Archaeological remains found in the coastal zone indicate that the area has been inhabited since the Bronze Age (ca. 2000 BC), but these societies, based on fishing in the extensive lagoons and rivers, have left few traces. Archaeological work also suggests that central Ghana north of the forest zone was inhabited as early as 3,000 to 4,000 years ago.[5]

These migrations resulted in part from the formation and disintegration of a series of large states in the western Sudan (the region north of modern Ghana drained by the Niger River). Strictly speaking, Ghana was the title of the king, but the Arabs, who left records of the kingdom, applied the term to the King, the capital, and the state. The 9th-century Berber historian and geographer Al Yaqubi described ancient Ghana as one of the three most organized states in the region (the others being Gao and Kanem in the central Sudan).[6]

Its rulers were renowned for their wealth in gold, the opulence of their courts, and their warrior/hunting skills. They were also masters of the trade in gold, which drew North African merchants to the western Sudan. The military achievements of these and later western Sudanic rulers, and their control over the region's gold mines, constituted the nexus of their historical relations with merchants and rulers in North Africa and the Mediterranean.[5]

Ghana succumbed to attacks by its neighbors in the 11th century, but its name and reputation endured. In 1957, when the leaders of the former British colony of the Gold Coast sought an appropriate name for their newly independent state—the first black African nation to gain its independence from colonial rule—they named their new country after ancient Ghana. The choice was more than merely symbolic, because modern Ghana, like its namesake, was equally famed for its wealth and trade in gold.[5]

Although none of the states of the western Sudan controlled territories in the area that is modern Ghana, several kingdoms that later developed such as Bonoman, were ruled by nobles believed to have immigrated from that region. The trans-Saharan trade that contributed to the expansion of kingdoms in the western Sudan also led to the development of contacts with regions in northern modern Ghana, and in the forest to the south.[5]

The growth of trade stimulated the development of early Akan states located on the trade route to the goldfields, in the forest zone of the south. The forest itself was thinly populated, but Akan-speaking peoples began to move into it toward the end of the 15th century, with the arrival of crops from South-east Asia and the New World that could be adapted to forest conditions. These new crops included sorghum, bananas, and cassava. By the beginning of the 16th century, European sources noted the existence of the gold-rich states of Akan and Twifu in the Ofin River Valley.[5]

According to oral traditions and archaeological evidence, the Dagomba states were the earliest kingdoms to emerge in present-day Ghana as early as the 11th century, being well established by the close of the 16th century.[5] Although the rulers of the Dagomba states were not usually Muslim, they brought with them, or welcomed, Muslims as scribes and medicine men. As a result of their presence, Islam influenced the north and Muslim influence spread by the activities of merchants and clerics.[5]

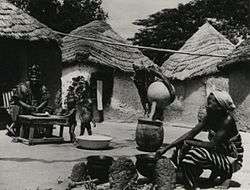

In the broad belt of rugged country between the northern boundaries of the Muslim-influenced state of Dagomba, and the southernmost outposts of the Mossi Kingdoms (of present-day northern Ghana and southern Burkina Faso), were peoples who were not incorporated into the Dagomba entity. Among these peoples were the Kassena agriculturalists. They lived in a so-called segmented society, bound together by kinship tie, and ruled by the head of their clan. Trade between Akan kingdoms and the Mossi kingdoms to the north flowed through their homeland, subjecting them to Islamic influence, and to the depredations of these more powerful control.

Ashanti Empire

Under Chief Oti Akenten (r. ca. 1630–60), a series of successful military operations against neighboring Akan states brought a larger surrounding territory into alliance with Ashanti. At the end of the 17th century, Osei Tutu (died 1712 or 1717) became Asantehene (king of Ashanti). Under Osei Tutu's rule, the confederacy of Ashanti states was transformed into an empire with its capital at Kumasi. Political and military consolidation ensued, resulting in firmly established centralized authority.[7]

Osei Tutu was strongly influenced by the high priest, Anokye, who, tradition asserts, caused a stool of gold to descend from the sky to seal the union of Ashanti states. Stools already functioned as traditional symbols of chieftainship, but the Golden Stool represented the united spirit of all the allied states and established a dual allegiance that superimposed the confederacy over the individual component states. The Golden Stool remains a respected national symbol of the traditional past and figures extensively in Ashanti ritual.[5]

Osei Tutu permitted newly conquered territories that joined the confederation to retain their own customs and chiefs, who were given seats on the Ashanti state council. Tutu's gesture made the process relatively easy and nondisruptive, because most of the earlier conquests had subjugated other Akan peoples. Within the Ashanti portions of the confederacy, each minor state continued to exercise internal self-rule, and its chief jealously guarded the state's prerogatives against encroachment by the central authority. A strong unity developed, however, as the various communities subordinated their individual interests to central authority in matters of national concern.[5]

By the mid-18th century, Ashanti was a highly organized state. The wars of expansion that brought the northern states of Dagomba,[8] Mamprusi, and Gonja[9] under Ashanti influence were won during the reign of Opoku Ware I (died 1750), successor to Osei Kofi Tutu I. By the 1820s, successive rulers had extended Ashanti boundaries southward. Although the northern expansions linked Ashanti with trade networks across the desert and in Hausaland to the east, movements into the south brought the Ashanti into contact, sometimes antagonistic, with the coastal Fante, as well as with the various European merchants whose fortresses dotted the Gold Coast.[5]

Early European contact and the slave trade

When the first Europeans arrived in the late 15th century, many inhabitants of the Gold Coast area were striving to consolidate their newly acquired territories and to settle into a secure and permanent environment. Initially, the Gold Coast did not participate in the export slave trade, rather as Ivor Wilks, a leading colonial historian of Ghana, noted, the Akan purchased slaves from Portuguese traders operating from other parts of Africa, including the Congo and Benin in order to augment the labour needed for the state formation that was characteristic of this period.[10]

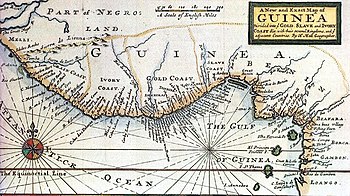

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive. By 1471, they had reached the area that was to become known as the Gold Coast.[11] The Gold Coast was so-named because it was an important source of gold. The Portuguese interest in trading for gold, ivory, and pepper so increased that in 1482 the Portuguese built their first permanent trading post on the western coast of present-day Ghana. This fortress, a trade castle called São Jorge da Mina (later called Elmina Castle), was constructed to protect Portuguese trade from European competitors, and after frequent rebuildings and modifications, still stands.[10]

The Portuguese position on the Gold Coast remained secure for over a century. During that time, Lisbon sought to monopolize all trade in the region in royal hands, though appointed officials at São Jorge, and used force to prevent English, French, and Flemish efforts to trade on the coast. By 1598, the Dutch began trading on the Gold Coast.[12] The Dutch built forts at Komenda and Kormantsi by 1612. In 1637 they captured Elmina Castle from the Portuguese and Axim in 1642 (Fort St Anthony). Other European traders joined in by the mid-17th century, largely English, Danes, and Swedes. The coastline was dotted by more than 30 forts and castles built by Dutch, British, and Danish merchants primarily to protect their interests from other Europeans and pirates. The Gold Coast became the highest concentration of European military architecture outside of Europe. Sometimes they were also drawn into conflicts with local inhabitants as Europeans developed commercial alliances with local political authorities. These alliances, often complicated, involved both Europeans attempting to enlist or persuade their closest allies to attack rival European ports and their African allies, or conversely, various African powers seeking to recruit Europeans as mercenaries in their inter-state wars, or as diplomats to resolve conflicts.[10]

Forts were built, abandoned, attacked, captured, sold, and exchanged, and many sites were selected at one time or another for fortified positions by contending European nations.[10]

The Dutch West India Company operated throughout most of the 18th century. The British African Company of Merchants, founded in 1750, was the successor to several earlier organizations of this type. These enterprises built and manned new installations as the companies pursued their trading activities and defended their respective jurisdictions with varying degrees of government backing. There were short-lived ventures by the Swedes and the Prussians. The Danes remained until 1850, when they withdrew from the Gold Coast. The British gained possession of all Dutch coastal forts by the last quarter of the 19th century, thus making them the dominant European power on the Gold Coast.[10]

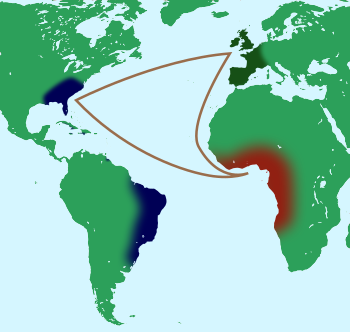

In the late 17th century, social changes within the polities of the Gold Coast led to transformations in warfare, and to the shift from being a gold exporting and slave importing economy to being a major local slave exporting economy.[13]

Some scholars have challenged the premise that rulers on the Gold Coast engaged in wars of expansion for the sole purpose of acquiring slaves for the export market. For example, the Ashanti waged war mainly to pacify territories that in were under Ashanti control, to exact tribute payments from subordinate kingdoms, and to secure access to trade routes—particularly those that connected the interior with the coast.[10]

The supply of slaves to the Gold Coast was entirely in African hands. Most rulers, such as the kings of various Akan states engaged in the slave trade, as well as individual local merchants.[10] A good number of the Slaves were also brought from various countries in the region and sold to middle men.

The demographic impact of the slave trade on West Africa was probably substantially greater than the number actually enslaved because a significant number of Africans perished during wars and bandit attacks or while in captivity awaiting transshipment. All nations with an interest in West Africa participated in the slave trade. Relations between the Europeans and the local populations were often strained, and distrust led to frequent clashes. Disease caused high losses among the Europeans engaged in the slave trade, but the profits realized from the trade continued to attract them.[10]

The growth of anti-slavery sentiment among Europeans made slow progress against vested African and European interests that were reaping profits from the traffic. Although individual clergymen condemned the slave trade as early as the 17th century, major Christian denominations did little to further early efforts at abolition. The Quakers, however, publicly declared themselves against slavery as early as 1727. Later in the century, the Danes stopped trading in slaves; Sweden and the Netherlands soon followed.[10]

In 1807, Britain used its naval power and its diplomatic muscle to outlaw trade in slaves by its citizens and to begin a campaign to stop the international trade in slaves.[14] The British withdrawal helped to decrease external slave trade.[15] The importation of slaves into the United States was outlawed in 1808. These efforts, however, were not successful until the 1860s because of the continued demand for plantation labour in the New World.[10]

Because it took decades to end the trade in slaves, some historians doubt that the humanitarian impulse inspired the abolitionist movement. According to historian Eric Williams, for example, Europe abolished the trans-Atlantic slave trade only because its profitability was undermined by the Industrial Revolution. Williams argued that mass unemployment caused by the new industrial machinery, the need for new raw materials, and European competition for markets for finished goods are the real factors that brought an end to the trade in human cargo and the beginning of competition for colonial territories in Africa. Other scholars, however, disagree with Williams, arguing that humanitarian concerns as well as social and economic factors were instrumental in ending the African slave trade.[10]

British Gold Coast

Britain and the Gold Coast: the early years

By the later part of the 19th century the Dutch and the British were the only traders left and after the Dutch withdrew in 1874, Britain made the Gold Coast a protectorate—a British Crown Colony. During the previous few centuries parts of the area were controlled by British, Portuguese, and Scandinavian powers, with the British ultimately prevailing. These nation-states maintained varying alliances with the colonial powers and each other, which resulted in the 1806 Ashanti-Fante War, as well as an ongoing struggle by the Empire of Ashanti against the British, the four Anglo-Ashanti Wars.

By the early 19th century the British acquired most of the forts along the coast. About one tenth of the total slave trades that occurred happened on the Gold Coast.[16] Two major factors laid the foundations of British rule and the eventual establishment of a colony on the Gold Coast: British reaction to the Ashanti wars and the resulting instability and disruption of trade, and Britain's increasing preoccupation with the suppression and elimination of the slave trade.[17]

During most of the 19th century, Ashanti, the most powerful state of the Akan interior, sought to expand its rule and to promote and protect its trade. The first Ashanti invasion of the coastal regions took place in 1807; the Ashanti moved south again in 1811 and in 1814. These invasions, though not decisive, disrupted trade in such products as gold, timber, and palm oil, and threatened the security of the European forts. Local British, Dutch, and Danish authorities were all forced to come to terms with Ashanti, and in 1817 the African Company of Merchants signed a treaty of friendship that recognized Ashanti claims to sovereignty over large areas of the coast and its peoples.[17]

The coastal people, primarily some of the Fante and the inhabitants of the new town of Accra came to rely on British protection against Ashanti incursions, but the ability of the merchant companies to provide this security was limited. The British Crown dissolved the company in 1821, giving authority over British forts on the Gold Coast to Governor Charles MacCarthy, governor of Sierra Leone. The British forts and Sierra Leone remained under common administration for the first half of the century. MacCarthy's mandate was to impose peace and to end the slave trade. He sought to do this by encouraging the coastal peoples to oppose Kumasi rule and by closing the great roads to the coast. Incidents and sporadic warfare continued, however. In 1823, the First Anglo-Ashanti War broke out and lasted until 1831.[14] MacCarthy was killed, and most of his force was wiped out in a battle with Ashanti forces in 1824.[17]

When the English government allowed control of the Gold Coast settlements to revert to the British African Company of Merchants in the late 1820s, relations with the Ashanti were still problematic. From the Ashanti point of view, the British had failed to control the activities of their local coastal allies. Had this been done, Ashanti might not have found it necessary to attempt to impose peace on the coastal peoples. MacCarthy's encouragement of coastal opposition to Ashanti and the subsequent 1824 British military attack further indicated to the Ashanti authorities that the Europeans, especially the British, did not respect Ashanti.[17]

In 1830 a London committee of merchants chose Captain George Maclean to become president of a local council of merchants. Although his formal jurisdiction was limited, Maclean's achievements were substantial. For example, a peace treaty was arranged with the Ashanti in 1831. Maclean also supervised the coastal people by holding regular court in Cape Coast where he punished those found guilty of disturbing the peace. Between 1830 and 1843 while Maclean was in charge of affairs on the Gold Coast, no confrontations occurred with Ashanti, and the volume of trade reportedly increased threefold.[17]

Maclean's exercise of limited judicial power on the coast was so effective that a parliamentary committee recommended that the British government permanently administer its settlements and negotiate treaties with the coastal chiefs that would define Britain's relations with them. The government did so in 1843, the same year crown government was reinstated. Commander H. Worsley Hill was appointed first governor of the Gold Coast. Under Maclean's administration, several coastal tribes had submitted voluntarily to British protection. Hill proceeded to define the conditions and responsibilities of his jurisdiction over the protected areas. He negotiated a special treaty with a number of Fante and other local chiefs that became known as the Bond of 1844. This document obliged local leaders to submit serious crimes, such as murder and robbery, to British jurisdiction and laid the legal foundation for subsequent British colonization of the coastal area.[17]

Additional coastal states as well as other states farther inland eventually signed the Bond, and British influence was accepted, strengthened, and expanded. Under the terms of the 1844 arrangement, the British gave the impression that they would protect the coastal areas; thus, an informal protectorate came into being. As responsibilities for defending local allies and managing the affairs of the coastal protectorate increased, the administration of the Gold Coast was separated from that of Sierra Leone in 1850.[17]

At about the same time, growing acceptance of the advantages offered by the British presence led to the initiation of another important step. In April 1852, local chiefs and elders met at Cape Coast to consult with the governor on means of raising revenue. With the governor's approval, the council of chiefs constituted itself as a legislative assembly. In approving its resolutions, the governor indicated that the assembly of chiefs should become a permanent fixture of the protectorate's constitutional machinery, but the assembly was given no specific constitutional authority to pass laws or to levy taxes without the consent of the people.[17]

The Second Anglo-Ashanti War broke out in 1863 and lasted until 1864. In 1872, British influence over the Gold Coast increased further when Britain purchased Elmina Castle, the last of the Dutch forts along the coast.[18] The Ashanti, who for years had considered the Dutch at Elmina as their allies, thereby lost their last trade outlet to the sea. To prevent this loss and to ensure that revenue received from that post continued, the Ashanti staged their last invasion of the coast in 1873. After early successes, they finally came up against well-trained British forces who compelled them to retreat beyond the Pra River. Later attempts to negotiate a settlement of the conflict with the British were rejected by the commander of their forces, Major General Sir Garnet Wolseley. To settle the Ashanti problem permanently, the British invaded Ashanti with a sizable military force. This invasion initiated the Third Anglo-Ashanti War. The attack, which was launched in January 1874 by 2,500 British soldiers and large numbers of African auxiliaries, resulted in the occupation and burning of Kumasi, the Ashanti capital.[17]

The subsequent peace treaty of 1875, required the Ashanti to renounce any claim to many southern territories. The Ashanti also had to keep the road to Kumasi open to trade. From this point on, Ashanti power steadily declined. The confederation slowly disintegrated as subject territories broke away and as protected regions defected to British rule. The warrior spirit of the nation was not entirely subdued, however, and enforcement of the treaty led to recurring difficulties and outbreaks of fighting. In 1896, the British dispatched another expedition that again occupied Kumasi and that forced Ashanti to become a protectorate of the British Crown. This became the Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War which lasted from 1894 until 1896. The position of "Asantehene" was abolished and the incumbent, Prempeh I, was exiled.[17] A British resident was installed at Kumasi.[19]

The core of the Ashanti federation accepted these terms grudgingly. In 1900 the Ashanti rebelled again (the War of the Golden Stool) but were defeated the next year. On 26 September 1901 the British annexed Ashanti to form part of Her Majesty’s dominions constituting the Ashanti as a Crown Colony. The new colony was placed under the jurisdiction of the governor of the Gold Coast.[19] The annexation was made with misgivings and recriminations on both sides. With Ashanti, and golden district subdued and annexed, British colonization of the region became a reality.[17]

Protestant missions

The Protestant nations in Western Europe, including Britain, had a vigorous evangelical element in the 19th century that felt their nations had a duty to "civilize" what they saw as slaves, sinners, and savages. Along with business opportunities, and the quest for national glory, the evangelical mission to save souls for Christ was a powerful impulse to imperialism. Practically all of Western Africa consisted of slave societies, in which warfare to capture new slaves—and perhaps sell them to itinerant slave traders—was a well-established economic, social, and political situation. The missionaries first of all targeted the slave trade, but they insisted that both the slave trade in the practice of traditional slavery were morally abhorrent. They worked hard and organized to abolish the trade. The transoceanic slave ships were targeted by the Royal Navy, and the trade faded away. Overland slave trading, practiced especially by Muslim traders from northeastern Africa, continued apace until the early 20th century. The abolition of slavery did not end the forced labor of children, however. The first missionaries to pre-colonial Ghana, were a multiracial mixture of European, African, and Caribbean pietists employed by Switzerland's Basel Mission. The policies were adopted by later missionary organizations.[20]

The Basel Mission had tight budgets and depended on child labor for many routine operations. The children were students in the mission schools who split their time between general education, religious studies, and unpaid labor. The Basel Mission made it a priority to alleviate the harsh conditions of child labor imposed by slavery, and the debt bondage of their parents.[21]

British rule of the Gold Coast: the colonial era

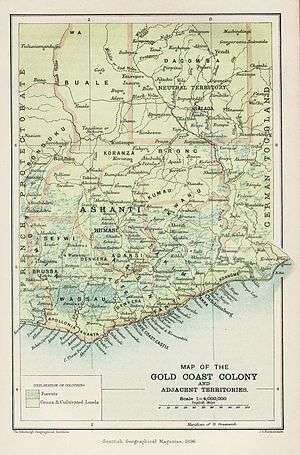

Military confrontations between Ashanti and the Fante contributed to the growth of British influence on the Gold Coast, as the Fante states—concerned about Ashanti activities on the coast—signed the Bond of 1844 at Fomena-Adansi, that allowed the British to usurp judicial authority from African courts. As a result of the exercise of ever-expanding judicial powers on the coast and also to ensure that the coastal peoples remained firmly under control, the British proclaimed the existence of the Gold Coast Colony on July 24, 1874, which extended from the coast inland to the edge of Ashanti territory. Though the coastal peoples were unenthusiastic about this development, there was no popular resistance, likely because the British made no claim to any rights to the land.[22]

In 1896, a British military force invaded Ashanti and overthrew the native Asantehene named Prempeh I.[19] The deposed Ashanti leader was replaced by a British resident at Kumasi.[19] The British sphere of influence was, thus, extended to include Ashanti following their defeat in 1896. However, British Governor Hodgson went too far in his restrictions on the Ashanti, when, in 1900, he demanded the "Golden Stool," the symbol of Ashanti rule and independence for the Ashanti. This caused another Ashanti revolt against the British colonizers.[19] The Ashanti were defeated again in 1901. Once the Asantehene and his council had been exiled, the British appointed a resident commissioner to Ashanti. Each Ashanti state was administered as a separate entity and was ultimately responsible to the governor of the Gold Coast.

In the meantime, the British became interested in the Northern Territories north of Ashanti, which they believed would forestall the advances of the French and the Germans. After 1896 protection was extended to northern areas whose trade with the coast had been controlled by Ashanti. In 1898 and 1899, European colonial powers amicably demarcated the boundaries between the Northern Territories and the surrounding French and German colonies. The Northern Territories of the Gold Coast Protectorate was established as British protectorate on 26 September 1901. Unlike the Ashanti Colony, the Northern Territories were not annexed. However, like the Ashanti Colony they were placed under the authority of a resident commissioner who was responsible to the Governor of the Gold Coast. The Governor ruled both Ashanti and the Northern Territories by proclamations until 1946.[22]

With the north under British control, the three territories of the Gold Coast—the Colony (the coastal regions), Ashanti, and the Northern Territories—became, for all practical purposes, a single political unit, or crown colony, known as the Gold Coast. The borders of present-day Ghana were realized in May 1956 when the people of the Volta region, known as British Mandated Togoland, a vote was made in a plebiscite on whether British Togoland should become part of modern Ghana; the Togoland Congress voted 42% against. 58% of votes opted for integration.[22]

Colonial administration

Beginning in 1850, the coastal regions increasingly came under control of the governor of the British fortresses, who was assisted by the Executive Council and the Legislative Council. The Executive Council was a small advisory body of European officials that recommended laws and voted taxes, subject to the governor's approval. The Legislative Council included the members of the Executive Council and unofficial members initially chosen from British commercial interests. After 1900 three chiefs and three other Africans were added to the Legislative Council, though the inclusion of Africans from Ashanti and the Northern Territories did not take place until much later.[23]

The gradual emergence of centralized colonial government brought about unified control over local services, although the actual administration of these services was still delegated to local authorities. Specific duties and responsibilities came to be clearly delineated, and the role of traditional states in local administration was also clarified. The structure of local government had its roots in traditional patterns of government. Village councils of chiefs and elders were responsible for the immediate needs of individual localities, including traditional law and order and the general welfare. The councils ruled by consent rather than by right: though chosen by the ruling class, a chief continued to rule because he was accepted by his people.[23]

British authorities adopted a system of indirect rule for colonial administration, wherein traditional chiefs maintained power but took instructions from their European supervisors. Indirect rule was cost-effective (by reducing the number of European officials needed), minimized local opposition to European rule, and guaranteed law and order. Though theoretically decentralizing, indirect rule in practice caused chiefs to look to Accra (the capital) rather than to their people for decisions. Many chiefs, who were rewarded with honors, decorations, and knighthood by government commissioners, came to regard themselves as a ruling aristocracy. In its preservation of traditional forms of power, indirect rule failed to provide opportunities for the country's growing population of educated young men. Other groups were dissatisfied because there was insufficient cooperation between the councils and the central government and because some felt that the local authorities were too dominated by the British district commissioners.[23]

In 1925 provincial councils of chiefs were established in all three territories of the colony, partly to give the chiefs a colony-wide function. The 1927 Native Administration Ordinance clarified and regulated the powers and areas of jurisdiction of chiefs and councils. In 1935 the Native Authorities Ordinance combined the central colonial government and the local authorities into a single governing system. New native authorities, appointed by the governor, were given wide powers of local government under the supervision of the central government's provincial commissioners, who made sure that their policies would be those of the central government. The provincial councils and moves to strengthen them were not popular. Even by British standards, the chiefs were not given enough power to be effective instruments of indirect rule. Some Ghanaians believed that the reforms, by increasing the power of the chiefs at the expense of local initiative, permitted the colonial government to avoid movement toward any form of popular participation in the colony's government.[23]

Economic and social development

The years of British administration of the Gold Coast during the 20th century were an era of significant progress in social, economic, and educational development. Communications and railroads were greatly improved. New crops were introduced. A leading crop that was the result of an introduced crop was coffee.[24] However, most spectacular among these introduced crops was the cacao tree which had been indigenous to the New World and had been introduced in Africa by the Spanish and Portuguese.[24] Cacao had been introduced to the Gold Coast in 1879 by Tetteh Quashie, a blacksmith from Gold Coast.[25] Cacao tree raising and farming became widely accepted in the eastern part of the Gold Coast.[24]

In 1891, the Gold Coast exported 80 lbs of cacao worth no more than 4 pounds sterling. By the 1920s cacao exports had passed 200,000 tons and had reached a value of 4.7 million pounds sterling. By 1928, cacao exports had reached 11.7 million pounds sterling.[26] From 1890 to 1911, cocoa exports went from zero to one of the largest in the world.[27] Thus, cacao production became a major part of the economy of the Gold coast and later a major part of Ghana's economy.[28]

The colony's earnings increased further from the export of timber and gold. Revenue from export of the colony's natural resources financed internal improvements in infrastructure and social services. The foundation of an educational system more advanced than any other else in West Africa also resulted from mineral export revenue. It was through British-style education that a new Ghanaian elite gained the means and the desire to strive for independence. From beginnings in missionary schools, the early part of the 20th century saw the opening of secondary schools and the country's first institute of higher learning.[28]

Many of the economic and social improvements in the Gold Coast in the early part of the 20th century have been attributed to the Canadian-born Gordon Guggisberg, governor from 1919 to 1927.[29] Within the first six weeks of his governorship, he presented a ten-year development programme to the Legislative Council.[29] He suggested first the improvement of transportation. Then, in order of priority, his prescribed improvements included water supply, drainage, hydroelectric projects, public buildings, town improvements, schools, hospitals, prisons, communication lines, and other services. Guggisberg also set a goal of filling half of the colony's technical positions with Africans as soon as they could be trained. His programme has been described as the most ambitious ever proposed in West Africa up to that time.[28]

The colony assisted Britain in both World War I and World War II. In the ensuing years, however, postwar inflation and instability severely hampered readjustment for returning veterans, who were in the forefront of growing discontent and unrest. Their war service and veterans' associations had broadened their horizons, making it difficult for them to return to the humble and circumscribed positions set aside for Africans by the colonial authorities.[28]

The growth of nationalism and the end of colonial rule

As Ghana developed economically, education of the citizenry progressed apace. In 1890 there were only 5 government and 49 "assisted" mission schools in the whole of the Gold Coast with a total enrollment of only 5,000.[30] By 1920 there were 20 governmental schools, 188 "assisted" mission and 309 "unassisted" mission schools with a total enrollment of 43,000 pupils.[30] By 1940, there were 91,000 children attending Gold Coast schools. By 1950, the 279,000 children attending some 3,000 schools in the Gold Coast.[30] This meant that, in 1950, 43.6% of the school-age children in the Gold Coast colony were attending school.[30]

Thus by the end of the Second World War, the Gold Coast colony was the richest and most educated territories in West Africa.[30] Within this educated environment, the focus of government power gradually shifted from the hands of the governor and his officials into those of Ghanaians, themselves. The changes resulted from the gradual development of a strong spirit of nationalism and were to result eventually in independence. The development of national consciousness accelerated quickly in the post-World War II era, when, in addition to ex-servicemen, a substantial group of urban African workers and traders emerged to lend mass support to the aspirations of a small educated minority.

Early manifestations of nationalism in Ghana

By the late 19th century, a growing number of educated Africans increasingly found unacceptable an arbitrary political system that placed almost all power in the hands of the governor through his appointment of council members. In the 1890s, some members of the educated coastal elite organized themselves into the Aborigines' Rights Protection Society to protest a land bill that threatened traditional land tenure. This protest helped lay the foundation for political action that would ultimately lead to independence. In 1920, one of the African members of the Legislative Council, Joseph E. Casely-Hayford, convened the National Congress of British West Africa.[31] The National Congress demanded a wide range of reforms and innovations for British West Africa.[31]

The National Congress sent a delegation to London to urge the Colonial Office to consider the principle of elected representation. The group, which claimed to speak for all British West African colonies, represented the first expression of political solidarity between intellectuals and nationalists of the area. Though the delegation was not received in London (on the grounds that it represented only the interests of a small group of urbanized Africans), its actions aroused considerable support among the African elite at home.[32]

Notwithstanding their call for elected representation as opposed to a system whereby the governor appointed council members, these nationalists insisted that they were loyal to the British Crown and that they merely sought an extension of British political and social practices to Africans. Notable leaders included Africanus Horton, the writer John Mensah Sarbah, and S. R. B. Attah-Ahoma. Such men gave the nationalist movement a distinctly elitist flavour that was to last until the late 1940s.[32]

The constitution of April 8, 1925, promulgated by Guggisberg, created provincial councils of paramount chiefs for all but the northern provinces of the colony. These councils in turn elected six chiefs as unofficial members of the Legislative Council, which however had an inbuilt British majority and whose powers were in any case purely advisory. Although the new constitution appeared to recognize some African sentiments, Guggisberg was concerned primarily with protecting British interests. For example, he provided Africans with a limited voice in the central government; yet, by limiting nominations to chiefs, he drove a wedge between chiefs and their educated subjects. The intellectuals believed that the chiefs, in return for British support, had allowed the provincial councils to fall completely under control of the government. By the mid-1930s, however, a gradual rapprochement between chiefs and intellectuals had begun.[32]

Agitation for more adequate representation continued. Newspapers owned and managed by Africans played a major part in provoking this discontent—six were being published in the 1930s. As a result of the call for broader representation, two more unofficial African members were added to the Executive Council in 1943. Changes in the Legislative Council, however, had to await a different political climate in London, which came about only with the postwar election of a British Labour Party government.[32]

The new Gold Coast constitution of March 29, 1946 (also known as the Burns constitution after the governor of the time, Sir Alan Cuthbert Maxwell Burns) was a bold document. For the first time, the concept of an official majority was abandoned. The Legislative Council was now composed of six ex-officio members, six nominated members, and eighteen elected members, however the Legislative Council continued to have purely advisory powers – all executive power remained with the governor. The 1946 constitution also admitted representatives from Ashanti into the council for the first time. Even with a Labour Party government in power, however, the British continued to view the colonies as a source of raw materials that were needed to strengthen their crippled economy. Change that would place real power in African hands was not a priority among British leaders until after rioting and looting in Accra and other towns and cities in early 1948 over issues of pensions for ex-servicemen, the dominant role of settler-colonists in the economy, the shortage of housing, and other economic and political grievances.[32]

With elected members in a decisive majority, Ghana had reached a level of political maturity unequalled anywhere in colonial Africa. The constitution did not, however, grant full self-government. Executive power remained in the hands of the governor, to whom the Legislative Council was responsible. Hence, the constitution, although greeted with enthusiasm as a significant milestone, soon encountered trouble. World War II had just ended, and many Gold Coast veterans who had served in British overseas expeditions returned to a country beset with shortages, inflation, unemployment, and black-market practices. There veterans, along with discontented urban elements, formed a nucleus of malcontents ripe for disruptive action. They were now joined by farmers, who resented drastic governmental measures required to cut out diseased cacao trees in order to control an epidemic, and by many others who were unhappy that the end of the war had not been followed by economic improvements.[32]

Politics of the independence movements

Although political organizations had existed in the British colony, the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), founded on 4 August 1947 by educated Ghanaians known as The Big Six, was the first nationalist movement with the aim of self-government "in the shortest possible time." It called for the replacement of chiefs on the Legislative Council with educated persons. They also demanded that, given their education, the colonial administration should respect them and accord them positions of responsibility. In particular, the UGCC leadership criticized the government for its failure to solve the problems of unemployment, inflation, and the disturbances that had come to characterize the society at the end of the war. Though they opposed the colonial administration, UGCC members did not seek drastic or revolutionary change. Public dissatisfaction with the UGCC expressed itself on February 28, 1948 as a demonstration of ex-servicemen organized by the ex-serviceman's union paraded through Accra.[33] To disperse the demonstrators, police fired on them killing three ex-servicemen and wounding sixty. Five days of violent disorder followed in Accra in response to the shooting and rioters broke into and looted the shops owned by Europeans and Syrians.[34] Rioting also broke out in Kumasi and other towns across the Gold Coast. The Big Six including Nkrumah were imprisoned by the British authorities from 12 March to 12 April 1948. The police shooting and the resultant riots indicated that the gentlemanly manner in which politics had been conducted by the UGCC was irrelevant in the new post-war world. This change in the dynamics of politics of the Gold Coast was not lost on Kwame Nkrumah who broke with the UGCC publicly during its Easter Convention in 1949, and created his Convention People's Party (CPP) on 12 June 1949.[35]

After his brief tenure with the UGCC, the US- and British-educated Nkrumah broke with the organization over his frustration at the UGCC's weak attempts to solve the problems of the Gold Coast colony by negotiating another new conciliatory colonial constitution with the British colonial authority.[34] Unlike the UGCC's call for self-government "in the shortest possible time," Nkrumah and the CPP asked for "self-government now." The party leadership identified itself more with ordinary working people than with the UGCC and its intelligentsia, and the movement found support among workers, farmers, youths, and market women. The politicized population consisted largely of ex-servicemen, literate persons, journalists, and elementary school teachers, all of whom had developed a taste for populist conceptions of democracy. A growing number of uneducated but urbanized industrial workers also formed part of the support group. By June 1949, Nkrumah had a mass following.[35]

The constitution of January 1, 1951, resulted from the report of the Coussey Committee, created because of disturbances in Accra and other cities in 1948. In addition to giving the Executive Council a large majority of African ministers, it created an assembly, half the elected members of which were to come from the towns and rural districts and half from the traditional councils. Although it was an enormous step forward, the new constitution still fell far short of the CPP's call for full self-government. Executive power remained in British hands, and the legislature was tailored to permit control by traditionalist interests.[35]

With increasing popular backing, the CPP in early 1950 initiated a campaign of "Positive Action" intended to instigate widespread strikes and nonviolent resistance. When some violent disorders occurred on January 20, 1950, Nkrumah was arrested and imprisoned for sedition. This merely established him as a leader and hero, building popular support, and when the first elections were held for the Legislative Assembly under the new constitution from February 5–10, 1951, Nkrumah (still in jail) won a seat, and the CPP won a two-thirds majority of votes cast winning 34 of the 38 elected seats in the Assembly. Nkrumah was released from jail on 11 February 1951, and the following day accepted an invitation to form a government as "leader of government business," a position similar to that of prime minister. The start of Nkrumah's first term was marked by cooperation with the British governor. During the next few years, the government was gradually transformed into a full parliamentary system. The changes were opposed by the more traditionalist African elements, though opposition proved ineffective in the face of popular support for independence at an early date.[35]

On March 10, 1952, the new position of Prime Minister was created, and Nkrumah was elected to the post by the Assembly. At the same time the Executive Council became the Cabinet. The new constitution of 5 May 1954 ended the election of assembly members by the tribal councils. The Legislative Assembly increased in size, and all members were chosen by direct election from equal, single-member constituencies. Only defense and foreign policy remained in the hands of the Governor; the elected assembly was given control of virtually all internal affairs of the Colony.[35] The CPP won 71 of the 104 seats in the 15 June 1954 election.

The CPP pursued a policy of political centralization, which encountered serious opposition. Shortly after the 15 June 1954 election, a new party, the Ashanti-based National Liberation Movement (NLM), was formed. The NLM advocated a federal form of government, with increased powers for the various regions. NLM leaders criticized the CPP for perceived dictatorial tendencies. The new party worked in cooperation with another regionalist group, the Northern People's Party. When these two regional parties walked out of discussions on a new constitution, the CPP feared that London might consider such disunity an indication that the colony was not yet ready for the next phase of self-government.[35]

The British constitutional adviser, however, backed the CPP position. The governor dissolved the assembly in order to test popular support for the CPP demand for immediate independence. On 11 May 1956 the British agreed to grant independence if so requested by a 'reasonable' majority of the new legislature.[36] New elections were held on 17 July 1956. In keenly contested elections, the CPP won 57 percent of the votes cast, but the fragmentation of the opposition gave the CPP every seat in the south as well as enough seats in Ashanti, the Northern Territories, and the Trans-Volta Region to hold a two-thirds majority by winning 72 of the 104 seats.[35]

On May 9, 1956, a plebiscite was conducted under United Nations (UN) auspices to decide the future disposition of British Togoland and French Togoland. The British trusteeship, the western portion of the former German colony, had been linked to the Gold Coast since 1919 and was represented in its parliament. The dominant ethnic group, the Ewe people, were divided between the two Togos. A majority (58%) of British Togoland inhabitants voted in favour of union, and the area was absorbed into Ashantiland and Dagbon. There was, however, vocal opposition to the incorporation from the Ewe people (42%) in British Togoland.[35]

Moving toward independence

In 1945 a Conference (known as the 5th Pan-African Congress) was held in Manchester to promote Pan-African ideas. This was attended by Nkrumah of Ghana, Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria and I. T. A. Wallace-Johnson of Sierra Leone. The Indian and Pakistani independence catalysed this desire. There was also the rejection of African culture to some extent. Some external forces also contributed to this feeling. African-Americans such as W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey (Afro-Jamaican) raised strong Pan-African conscience.

Sir Alan Burns constitution of 1946 provided new legislative council that was made of the Governor as the President, 6 government officials, 6 nominated members and 18 elected members.

The executive council was not responsible to the legislative council. They were only in advisory capacity, and the governor did not have to take notice.

These forces made Dr J. B. Danquah form the United Gold Coast Conversion (UGCC) in 1947, and Nkrumah was invited to be this party's General Secretary. Other officers were George Alfred Grant (Paa Grant), Edward Akufo-Addo, William Ofori Atta, Emmanuel Obetsebi-Lamptey, Ebenezer Ako-Adjei, and J. Tsiboe. Their aim was Independence for Ghana. They rejected the Burns constitution amendment of a number of its clauses. It also granted a voice to chiefs and their tribal councils by providing for the creation of regional assemblies. No bill amending the entrenched clauses of the constitution or affecting the powers of the regional bodies or the privileges of the chiefs could become law except by a two-thirds vote of the National Assembly and by simple majority approval in two-thirds of the regional assemblies. When local CPP supporters gained control of enough regional assemblies, however, the Nkrumah government promptly secured passage of an act removing the special entrenchment protection clause in the constitution, a step that left the National Assembly with the power to effect any constitutional change the CPP deemed necessary.[37]

The electoral victory of the CCP in 1951 ushered in five years of power-sharing with the British. The economy prospered, with a high global demand and rising prices for cocoa. The efficiency of the Cocoa Marketing Board enabled the large profits to be spent on development of the infrastructure. There was a major expansion of schooling and modernizing projects such as the new industrial city at Tema.[38] Favored projects by Nkrumah included new organizations such as the Young Pioneers, for young people, and the Builder's Brigades for mechanization of agriculture. There were uniforms, parades, new patriotic songs, and the presentation of an ideal citizenship in which all citizens learned that there their primary duty was to the state.[39]

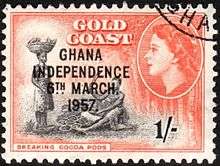

Ghana's independence achieved in 1957

On August 3, 1956, the new assembly passed a motion authorizing the government to request independence within the British Commonwealth.[40] The opposition did not attend the debate, and the vote was unanimous. The British government accepted this motion as clearly representing a reasonable majority, so on 18 September 1956 the British set 6 March 1957, the 113th anniversary of the Bond of 1844, as the date that the Gold Coast, Ashanti, the Northern Territories and British Togoland would together become a unified, independent dominion within the British Commonwealth of Nations under the name Ghana.[41] Nkrumah continued as prime minister, and Queen Elizabeth II as monarch, represented in the dominion by the Governor-General of Ghana, Sir Charles Noble Arden-Clarke. Dominion status would continue until 1960, when after a national referendum, Ghana was declared a Republic.[37]

The Second Development Plan of 1959-1964 followed the Soviet model, and shifted away from expanding state services toward raising productivity in the key sectors. Nkrumah believe that colonialism had twisted personalities, imposing a competitive, individualistic and bourgeois mentality that had to be eliminated. Worldwide cocoa prices began to fall, budgets were cut, and workers were called upon for more and more self sacrifice to overcome neocolonialism. Nkrumah drastically curtailed the independence of the labor unions, and when strikes resulted he cracked down through the Preventive Detention Act.[42]

.jpg)

On the domestic front, Nkrumah believed that rapid modernization of industries and communications was necessary and that it could be achieved if the workforce were completely Africanized and educated. Expansion of secondary schools became a high priority in 1959–1964, along with expansion of vocational programs and higher education.[43]

Crushing dissent

Even more important, however, Nkrumah believed that this domestic goal could be achieved faster if it were not hindered by reactionary politicians—elites in the opposition parties and traditional chiefs—who might compromise with Western imperialists. Indeed, the enemies could be anywhere and dissent was not tolerated.[44] Nkrumah's regime enacted the Deportation Act of 1957, the Detention Acts of 1958, 1959 and 1962, and carried out parliamentary intimidation of CPP opponents, the recognition of his party as the sole political organization of the state, the creation of the Young Pioneer Movement for the ideological education of the nation's youth, and the party's control of the civil service.[45] Government expenditure on road building projects, mass education of adults and children, and health services, as well as the construction of the Akosombo Dam, were all important if Ghana were to play its leading role in Africa's liberation from colonial and neo-colonial domination.[46]

Pan-Africanist dream

Nkrumah discussed his political views in his numerous writings, especially in Africa Must Unite (1963) and in NeoColonialism (1965). These writings show the impact of his stay in Britain in the mid-1940s. The pan-Africanist movement, which had held one of its annual conferences, attended by Nkrumah, at Manchester in 1945, was influenced by socialist ideologies. The movement sought unity among people of African descent and also improvement in the lives of workers who, it was alleged, had been exploited by capitalist enterprises in Africa. Western countries with colonial histories were identified as the exploiters. According to the socialists, "oppressed" people ought to identify with the socialist countries and organizations that best represented their interests; however, all the dominant world powers in the immediate post-1945 period, except the Soviet Union and the United States, had colonial ties with Africa. Nkrumah asserted that even the United States, which had never colonized any part of Africa, was in an advantageous position to exploit independent Africa unless preventive efforts were taken.[46]

According to Nkrumah, his government, which represented the first black African nation to win Independence, had an important role to play in the struggle against capitalist interests on the continent. As he put it, "the independence of Ghana would be meaningless unless it was tied to the total liberation of Africa." It was important, then, he said, for Ghanaian's to "seek first the political kingdom." Economic benefits associated with independence were to be enjoyed later, proponents of Nkrumah's position argued. But Nkrumah needed strategies to pursue his goals.[46]

On the continental level, Nkrumah sought to unite Africa so that it could defend its international economic interests and stand up against the political pressures from East and West that were a result of the Cold War. His dream for Africa was a continuation of the pan-Africanist dream as expressed at the Manchester conference. The initial strategy was to encourage revolutionary political movements in Africa. The CIA believed that Nkrumah's government provided money and training for pro-socialist guerrillas in Ghana, aided after 1964 by the Chinese Communist government. Several hundred trainees passed through this program, administered by Nkrumah's Bureau of African Affairs, and were sent on to countries such as Rhodesia, Angola, Mozambique, Niger and Congo.[47] Politically, Nkrumah believed that a Ghana, Guinea, and Mali union would serve as the psychological and political impetus for the formation of a United States of Africa. When Nkrumah was criticized for paying little attention to Ghana or for wasting national resources in supporting external programmes, he reversed the argument and accused his opponents of being short-sighted.[46]

Tax protests

The heavy financial burdens created by Nkrumah's development policies and pan-African adventures created new sources of opposition. With the presentation in July 1961 of the country's first austerity budget, Ghana's workers and farmers became aware of and critical of the cost to them of Nkrumah's programmes. Their reaction set the model for the protests over taxes and benefits that were to dominate Ghanaian political crises for the next thirty years.[46]

CPP backbenchers and UP representatives in the National Assembly sharply criticized the government's demand for increased taxes and, particularly, for a forced savings programme. Urban workers began a protest strike, the most serious of a number of public outcries against government measures during 1961. Nkrumah's public demands for an end to corruption in the government and the party further undermined popular faith in the national government. A drop in the price paid to cocoa farmers by the government marketing board aroused resentment among a segment of the population that had always been Nkrumah's major opponent.[46]

Growth of opposition to Nkrumah

Nkrumah's complete domination of political power had served to isolate lesser leaders, leaving each a real or imagined challenger to the ruler. After opposition parties were crushed, opponents came only from within the CPP hierarchy. Among its members was Tawia Adamafio, an Accra politician. Nkrumah had made him general secretary of the CPP for a brief time. Later, Adamafio was appointed minister of state for presidential affairs, the most important post in the president's staff at Flagstaff House, which gradually became the centre for all decision making and much of the real administrative machinery for both the CPP and the government. The other leader with an apparently autonomous base was John Tettegah, leader of the Trade Union Congress. Neither, however, proved to have any power other than that granted to them by the president.[48]

By 1961, however, the young and more radical members of the CPP leadership, led by Adamafio, had gained ascendancy over the original CPP leaders like Gbedemah. After a bomb attempt on Nkrumah's life in August 1962, Adamafio, Ako Adjei (then minister of foreign affairs), and Cofie Crabbe (all members of the CPP) were jailed under the Preventive Detention Act. The first Ghanaian Commissioner of Police, E. R. T Madjitey, from Asite in Manya-Krobo was also relieved of his post. The CPP newspapers charged them with complicity in the assassination attempt, offering as evidence only the fact that they had all chosen to ride in cars far behind the president's when the bomb was thrown.[48]

For more than a year, the trial of the alleged plotters of the 1962 assassination attempt occupied centre stage. The accused were brought to trial before the three-judge court for state security, headed by the chief justice, Sir Arku Korsah. When the court acquitted the accused, Nkrumah used his constitutional prerogative to dismiss Korsah. Nkrumah then obtained a vote from the parliament that allowed retrial of Adamafio and his associates. A new court, with a jury chosen by Nkrumah, found all the accused guilty and sentenced them to death. These sentences, however, were commuted to twenty years' imprisonment.[48]

Corruption had highly deleterious effects. It removed money from the active economy and put it in the hands of the political parties, and Nkrumah's friends and family, so it became an obstacle to economic growth. The new state companies that had been formed to implement growth became instruments of patronage and financial corruption; civil servants doubled their salaries and politicians purchase supporters. Politically, allegations and instances of corruption in the ruling party, and in Nkrumah's personal finances, undermined the very legitimacy of his regime and sharply decreased the ideological commitment needed to maintain the public welfare under Ghanaian socialism.[49]

Political scientist Herbert H. Werlin Has examined the mounting economic disaster:

- Nkrumah left Ghana with a serious balance-of-payments problem. Beginning with a substantial foreign reserve fund of over $500 million at the time of independence, Ghana, by 1966, had a public external debt of over $800 million.....there was no foreign exchange to buy the spare parts and raw materials required for the economy. While inflation was rampant, causing the price-level to rise by 30 per cent in 1964-65, unemployment was also serious....Whereas between 1955 and 1962 Ghana's GNP increased at an average annual rate of nearly 5 per cent, there was practically no growth at all by 1965....Since Ghana's estimated annual rate of population growth was 2.6 per cent, her economy was obviously retrogressing. While personal per capita consumption declined by some 15 per cent between 1960 and 1966, the real wage income of the minimum wage earner declined by some 45 per cent during this period.[50]

Fall of Nkrumah: 1966

In early 1964, in order to prevent future challenges from the judiciary and after another national referendum, Nkrumah obtained a constitutional amendment allowing him to dismiss any judge. Ghana officially became a one-party state and an act of parliament ensured that there would be only one candidate for president. Other parties having already been outlawed, no non-CPP candidates came forward to challenge the party slate in the general elections announced for June 1965. Nkrumah had been re-elected president of the country for less than a year when members of the National Liberation Council (NLC) overthrew the CPP government in a military coup on 24 February 1966. At the time, Nkrumah was in China. He took up asylum in Guinea, where he remained until he died in 1972.[48][51]

Since 1966

Leaders of the 1966 military coup justified their takeover by charging that the CPP administration was abusive and corrupt, that Nkrumah's involvement in African politics was overly aggressive, and that the nation lacked democratic practices. They claimed that the military coup of 1966 was a nationalist one because it liberated the nation from Nkrumah's dictatorship. All symbols and organizations linked to Nkrumah quickly vanished, such as the Young Pioneers.[52] Despite the vast political changes that were brought about by the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah, many problems remained, including ethnic and regional divisions, the country's economic burdens, and mixed emotions about a resurgence of an overly strong central authority. A considerable portion of the population had become convinced that effective, honest government was incompatible with competitive political parties. Many Ghanaians remained committed to nonpolitical leadership for the nation, even in the form of military rule. The problems of the Busia administration, the country's first elected government after Nkrumah's fall, illustrated the problems Ghana would continue to face.[53] It has been argued that the coup was supported by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency;[54][55]

The National Liberation Council (NLC), composed of four army officers and four police officers, assumed executive power. It appointed a cabinet of civil servants and promised to restore democratic government as quickly as possible. These moves culminated in the appointment of a representative assembly to draft a constitution for the Second Republic of Ghana. Political parties were allowed to operate beginning in late 1968. In Ghana's 1969 elections, the first competitive nationwide political contest since 1956, the major contenders were the Progress Party (PP), headed by Kofi Abrefa Busia, and the National Alliance of Liberals (NAL), led by Komla A. Gbedemah. The PP found much of its support among the old opponents of Nkrumah's CPP – the educated middle class and traditionalists of the Ashanti Region and the North. The NAL was seen as the successor of the CPP's right wing. Overall, the PP gained 59 percent of the popular vote and 74 percent of the seats in the National Assembly.[56]

Gbedemah, who was soon barred from taking his National Assembly seat by a Supreme Court decision, retired from politics, leaving the NAL without a strong leader. In October 1970, the NAL absorbed the members of three other minor parties in the assembly to form the Justice Party (JP) under the leadership of Joseph Appiah. Their combined strength constituted what amounted to a southern bloc with a solid constituency among most of the Ewe and the peoples of the coastal cities.[56]

PP leader Busia became prime minister in September 1970. After a brief period under an interim three-member presidential commission, the electoral college chose as president Chief Justice Edward Akufo-Addo, one of the leading nationalist politicians of the UGCC era and one of the judges dismissed by Nkrumah in 1964.[56]

All attention, however, remained focused on Prime Minister Busia and his government. Much was expected of the Busia administration, because its parliamentarians were considered intellectuals and, therefore, more perceptive in their evaluations of what needed to be done. Many Ghanaians hoped that their decisions would be in the general interest of the nation, as compared with those made by the Nkrumah administration, which were judged to satisfy narrow party interests and, more important, Nkrumah's personal agenda. The NLC had given assurances that there would be more democracy, more political maturity, and more freedom in Ghana, because the politicians allowed to run for the 1969 elections were proponents of Western democracy. In fact, these were the same individuals who had suffered under the old regime and were, therefore, thought to understand the benefits of democracy.[56]

Two early measures initiated by the Busia government were the expulsion of large numbers of non-citizens from the country and a companion measure to limit foreign involvement in small businesses. The moves were aimed at relieving the unemployment created by the country's precarious economic situation. The policies were popular because they forced out of the retail sector of the economy those foreigners, especially Lebanese, Asians, and Nigerians, who were perceived as unfairly monopolizing trade to the disadvantage of Ghanaians. Many other Busia moves, however, were not popular. Busia's decision to introduce a loan programme for university students, who had hitherto received free education, was challenged because it was interpreted as introducing a class system into the country's highest institutions of learning. Some observers even saw Busia's devaluation of the national currency and his encouragement of foreign investment in the industrial sector of the economy as conservative ideas that could undermine Ghana's sovereignty.[56]

The opposition Justice Party's basic policies did not differ significantly from those of the Busia administration. Still, the party attempted to stress the importance of the central government rather than that of limited private enterprise in economic development, and it continued to emphasize programmes of primary interest to the urban work force. The ruling PP emphasized the need for development in rural areas, both to slow the movement of population to the cities and to redress regional imbalance in levels of development. The JP and a growing number of PP members favoured suspension of payment on some foreign debts of the Nkrumah era. This attitude grew more popular as debt payments became more difficult to meet. Both parties favoured creation of a West African economic community or an economic union with the neighboring West African states.[56]

Despite broad popular support garnered at its inception and strong foreign connections, the Busia government fell victim to an army coup within twenty-seven months. Neither ethnic nor class differences played a role in the overthrow of the PP government. The crucial causes were the country's continuing economic difficulties, both those stemming from the high foreign debts incurred by Nkrumah and those resulting from internal problems. The PP government had inherited US$580 million in medium- and long-term debts, an amount equal to 25 percent of the gross domestic product of 1969. By 1971 the US$580 million had been further inflated by US$72 million in accrued interest payments and US$296 million in short-term commercial credits. Within the country, an even larger internal debt fueled inflation.[56]

Ghana's economy remained largely dependent upon the often difficult cultivation of and market for cocoa. Cocoa prices had always been volatile, but exports of this tropical crop normally provided about half of the country's foreign currency earnings. Beginning in the 1960s, however, a number of factors combined to limit severely this vital source of national income. These factors included foreign competition (particularly from neighboring Côte d'Ivoire), a lack of understanding of free-market forces (by the government in setting prices paid to farmers), accusations of bureaucratic incompetence in the Cocoa Marketing Board, and the smuggling of crops into Côte d'Ivoire. As a result, Ghana's income from cocoa exports continued to fall dramatically.[56]

Austerity measures imposed by the Busia administration, although wise in the long run, alienated influential farmers, who until then had been PP supporters. These measures were part of Busia's economic structural adjustment efforts to put the country on a sounder financial base. The austerity programmes had been recommended by the International Monetary Fund. The recovery measures also severely affected the middle class and the salaried work force, both of which faced wage freezes, tax increases, currency devaluations, and rising import prices. These measures precipitated protests from the Trade Union Congress. In response, the government sent the army to occupy the trade union headquarters and to block strike actions—a situation that some perceived as negating the government's claim to be operating democratically.[56]

The army troops and officers upon whom Busia relied for support were themselves affected, both in their personal lives and in the tightening of the defense budget, by these same austerity measures. As the leader of the anti-Busia coup declared on January 13, 1972, even those amenities enjoyed by the army during the Nkrumah regime were no longer available. Knowing that austerity had alienated the officers, the Busia government began to change the leadership of the army's combat elements. This, however, was the last straw. Lieutenant Colonel Ignatius Kutu Acheampong, temporarily commanding the First Brigade around Accra, led a bloodless coup that ended the Second Republic.[56]

National Redemption Council years, 1972–79

Despite its short existence, the Second Republic was significant in that the development problems the nation faced came clearly into focus. These included uneven distribution of investment funds and favouritism toward certain groups and regions. Important questions about developmental priorities remained unanswered, and after the failure of both the Nkrumah and the Busia regimes (one a one-party state, and the other a multi-party parliamentary democracy) Ghana's path to political stability was obscure.[57]

Acheampong's National Redemption Council (NRC) claimed that it had to act to remove the ill effects of the currency devaluation of the previous government and thereby, at least in the short run, to improve living conditions for individual Ghanaians. To justify their takeover, coup leaders leveled charges of corruption against Busia and his ministers. The NRC sought to create a truly military government and did not outline any plan for the return of the nation to democratic rule.[57]

In matters of economic policy, Busia's austerity measures were reversed, the Ghanaian currency was revalued upward, foreign debt was repudiated or unilaterally rescheduled, and all large foreign-owned companies were nationalized. The government also provided price supports for basic food imports, while seeking to encourage Ghanaians to become self-reliant in agriculture and the production of raw materials. These measures, while instantly popular, did nothing to solve the country's problems and in fact aggravated the problem of capital flow. Any economic successes were overridden by other basic economic factors. Industry and transportation suffered greatly as oil prices rose in 1974, and the lack of foreign exchange and credit left the country without fuel. Basic food production continued to decline even as the population grew. Disillusionment with the government developed, and accusations of corruption began to surface.[57]

The reorganization of the NRC into the Supreme Military Council (SMC) in 1975 may have been part of a face-saving attempt. Little input from the civilian sector was allowed, and military officers were put in charge of all ministries and state enterprises down to the local level. During the NRC's early years, these administrative changes led many Ghanaians to hope that the soldiers in command would improve the efficiency of the country's bloated bureaucracies.[57]

Shortly after that time, the government sought to stifle opposition by issuing a decree forbidding the propagation of rumors and by banning a number of independent newspapers and detaining their journalists. Also, armed soldiers broke up student demonstrations, and the government repeatedly closed the universities, which had become important centres of opposition to NRC policies. The self-appointed Ashanti General I. K. Acheampong seemed to have much sympathy for women than his ailing economic policies. As the Commissioner(Minister) of Finance, he signed Government checks to concubines and other ladies he barely knew. VW Gulf cars were imported and given to beautiful ladies he came across. Import licenses were given out to friends and ethnic affiliates with impunity.

The SMC by 1977 found itself constrained by mounting non-violent opposition. To be sure, discussions about the nation's political future and its relationship to the SMC had begun in earnest. Although the various opposition groups (university students, lawyers, and other organized civilian groups) called for a return to civilian constitutional rule, Acheampong and the SMC favoured a union government—a mixture of elected civilian and appointed military leaders—but one in which party politics would be abolished. University students and many intellectuals criticized the union government idea, but others, such as Justice Gustav Koranteng-Addow, who chaired the seventeen-member ad hoc committee appointed by the government to work out details of the plan, defended it as the solution to the nation's political problems. Supporters of the union government idea viewed multiparty political contests as the perpetrators of social tension and community conflict among classes, regions, and ethnic groups. Unionists argued that their plan had the potential to depoliticize public life and to allow the nation to concentrate its energies on economic problems.[57]

A national referendum was held in March 1978 to allow the people to accept or reject the union government concept. A rejection of the union government meant a continuation of military rule. Given this choice, it was surprising that so narrow a margin voted in favour of union government. Opponents of the idea organized demonstrations against the government, arguing that the referendum vote had not been free or fair. The Acheampong government reacted by banning several organizations and by jailing as many as 300 of its opponents.[57]

The agenda for change in the union government referendum called for the drafting of a new constitution by an SMC-appointed commission, the selection of a constituent assembly by November 1978, and general elections in June 1979. The ad hoc committee had recommended a nonparty election, an elected executive president, and a cabinet whose members would be drawn from outside a single-house National Assembly. The military council would then step down, although its members could run for office as individuals.[57]

In July 1978, in a sudden move, the other SMC officers forced Acheampong to resign, replacing him with Lieutenant General Frederick W. K. Akuffo. The SMC apparently acted in response to continuing pressure to find a solution to the country's economic dilemma. Inflation was estimated to be as high as 300 percent that year. There were shortages of basic commodities, and cocoa production fell to half its 1964 peak. The council was also motivated by Acheampong's failure to dampen rising political pressure for changes. Akuffo, the new SMC chairman, promised publicly to hand over political power to a new government to be elected by 1 July 1979.[57]