Empire of Thessalonica

Empire of Thessalonica (Greek: Αυτοκρατορία της Θεσσαλονίκης) is a historiographic term used by some modern scholars[1] to refer to the short-lived Byzantine Greek state centred on the city of Thessalonica between 1224 and 1246 (sensu stricto until 1242) and ruled by the Komnenodoukas dynasty of Epirus. At the time of its establishment, the Empire of Thessalonica, under the capable Theodore Komnenos Doukas, rivaled the Empire of Nicaea and the Second Bulgarian Empire as the strongest state in the region, and aspired to capturing Constantinople, putting an end to the Latin Empire, and restoring the Byzantine Empire that had been extinguished in 1204.

Empire of Thessalonica | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1224–1246 | |||||||||||||

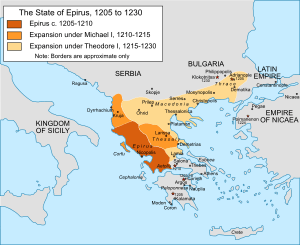

Conquests of the Komnenodoukas dynasty of Epirus until the Battle of Klokotnitsa | |||||||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Second Bulgarian Empire (1230–37) and of the Empire of Nicaea (1242–46) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Thessalonica | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Greek | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Greek Orthodoxy | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Emperor, after 1242 Despot | |||||||||||||

• 1224–1230 | Theodore Komnenos Doukas | ||||||||||||

• 1244–1246 | Demetrios Angelos Doukas | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||

• Fall of Thessalonica to Epirus | 1224 | ||||||||||||

• Fall of Thessalonica to Nicaea | 1246 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Thessalonica's ascendancy was brief, ending with the disastrous Battle of Klokotnitsa against Bulgaria in 1230, where Theodore Komnenos Doukas was captured. Reduced to a Bulgarian vassal, Theodore's brother and successor Manuel Komnenos Doukas was unable to prevent the loss of most of his brother's conquests in Macedonia and Thrace, while the original nucleus of the state, Epirus, broke free under Michael II Komnenos Doukas. Theodore recovered Thessalonica in 1237, installing his son John Komnenos Doukas, and after him Demetrios Angelos Doukas, as rulers of the city, while Manuel, with Nicaean support, seized Thessaly. The rulers of Thessalonica bore the imperial title from 1225/7 until 1242, when they were forced to renounce it and recognize the suzerainty of the rival Empire of Nicaea. The Komnenodoukai continued to rule as Despots of Thessalonica for four more years after that, but in 1246 the city was annexed by Nicaea.

Background

After the Fourth Crusade captured Constantinople in April 1204, the Byzantine Empire dissolved and was divided between the Crusader leaders and the Republic of Venice. The Latin Empire was set up in Constantinople itself, while most of northern and eastern mainland Greece went to the Kingdom of Thessalonica under Boniface of Montferrat.[2][3] At the same time, two major native Byzantine Greek states emerged to challenge the Latins and claim the Byzantine inheritance, the so-called Empire of Nicaea under Theodore I Laskaris in Asia Minor, and the so-called Despotate of Epirus in western Greece under Michael I Komnenos Doukas, while a third state, the so-called Empire of Trebizond, established a separate existence on the remote shores of the Pontus.[4][5] Michael I Komnenos Doukas soon extended his state into Thessaly, and his successor Theodore Komnenos Doukas captured Thessalonica in 1224.[6][7]

Rise and decline

The capture of Thessalonica, traditionally the second city of the Byzantine Empire after Constantinople, allowed Theodore to challenge the Nicaean claims on the Byzantine imperial title. With the support of the bishops of his domains, he was crowned emperor at Thessalonica by the Archbishop of Ohrid, Demetrios Chomatenos. The date is unknown, but has been placed either in 1225 or in 1227/8.[8][9] Having openly declared his imperial ambitions, Theodore turned his gaze onto Constantinople. Only the Nicaean emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes, and the Bulgarian emperor Ivan II Asen were strong enough to challenge him. In a bid to preempt Theodore, the Nicaeans seized Adrianople from the Latins in 1225, but Theodore quickly marched into Thrace and forced the Nicaeans to leave their European possessions to him. Theodore was free to assault Constantinople, but for unknown reasons delayed this attack. In the meantime, the Nicaeans and Latins had settled their differences, and although formally allied with Theodore, Ivan II Asen also entered talks for a dynastic alliance between the Latin Empire and Bulgaria.[10] In 1230, Theodore finally marched against Constantinople, but unexpectedly turned his army north into Bulgaria instead. In the ensuing Battle of Klokotnitsa, Theodore's army was destroyed and he himself taken captive and later blinded.[11][12]

This defeat abruptly diminished the power of Thessalonica. A state built upon rapid military expansion and relying on the ability of its ruler, its administration was unable to cope with defeat. Its territories in Thrace, as well as most of Macedonia and Albania rapidly fell to the Bulgarians, who emerged as the strongest Balkan power.[12][13] Theodore was succeeded by his brother Manuel Komnenos Doukas. He still controlled the environs of Thessalonica as well as the dynasty's lands in Thessaly and Epirus, but was forced to acknowledge himself Asen's vassal. In order to preserve some freedom of manoeuvre, Manuel even turned to his brother's erstwhile rivals in Nicaea, offering to acknowledge the superiority of Vatatzes and the Patriarch of Constantinople, who resided in Nicaea.[14] Manuel was also unable to prevent Michael II Komnenos Doukas, the bastard son of his older bastard half-brother, Michael I, from returning from exile in the aftermath of Klokotnitsa and seizing control of Epirus, where he apparently enjoyed considerable support. In the end Manuel was forced to accept the fait accompli, and recognized Michael II as ruler of Epirus under his own suzerainty. As sign of this, he conferred on Michael the title of Despot. From the start, Manuel's suzerainty was rather theoretical, and by 1236–37 Michael was acting as an independent ruler, seizing Corfu, and issuing charters and concluding treaties in his own name.[15]

Manuel's rule lasted until 1237, when he was deposed in a coup by Theodore. The latter had been released from captivity and secretly returned to Thessalonica after John II Asen fell in love with and married his daughter Irene. Having been blinded, Theodore could not claim the throne for himself and crowned his son John Komnenos Doukas, but remained the actual power behind the throne and virtual regent.[16][17] Manuel soon escaped and fled to Nicaea, where he pledged loyalty to Vatatzes. Thus in 1239 Manuel was allowed to sail to Thessaly, where he began assembling an army to march on Thessalonica. After he captured Larissa, Theodore offered him a settlement, whereby he and his son would keep Thessalonica, Manuel would keep Thessaly, while another brother, Constantine Komnenos Doukas, would rule over Aetolia and Acarnania, which he had held as an appanage since the 1220s. Manuel agreed and ruled Thessaly until his death in 1241, at which point it was quickly occupied by Michael II of Epirus.[18]

Submission to Nicaea

In 1241, on the assurance of safe conduct, Theodore went to Nicaea, but there Vatatzes held him prisoner, and in the next year he embarked with his army for Europe and marched on Thessalonica. Vatatzes had to break off the campaign and return to Nicaea when he received news of a Mongol invasion of Asia Minor, but managed to browbeat John into submission: in exchange for renouncing his imperial title and recognizing Nicaean authority, John was allowed to remain as ruler of Thessalonica with the title of Despot.[16][19]

In 1244, John died and was succeeded by his younger brother Demetrios Angelos Doukas. Demetrios was a frivolous ruler who quickly made himself unpopular with his subjects.[20] In 1246, Vatatzes once more crossed into Europe. In a three-month campaign he wrested much of Thrace as well as most of Macedonia from Bulgaria, which now became his vassal, while Michael II of Epirus also expanded his territory into western Macedonia.[21] After this remarkable success, Vatatzes turned on Thessalonica, where leading citizens were already conspiring to overthrow Demetrios and deliver the city to him. When Vatatzes appeared before the city, Demetrios refused to come out and pay homage to his suzerain, but Nicaean supporters inside the city opened a gate and let the Nicaean army in. Thessalonica was incorporated into the Nicaean state, with Andronikos Palaiologos as its governor, while Demetrios was sent to a comfortable exile in estates granted to him in Asia Minor. Conversely his father was exiled to Vodena.[16][22]

Aftermath

Despite the end of the Thessalonian state, Michael II of Epirus now took up the mantle of his family's claims. Michael tried to capture Thessalonica and re-establish a strong western Greek state able to challenge Nicaea for supremacy and the Byzantine imperial inheritance. A first assault in 1251–53, encouraged by the old Theodore Komnenos Doukas, failed, and Michael was forced to come to terms. This did not long deter Michael, who after 1257 sought alliances with other powers against the growing menace of Nicaea, including the Latin Principality of Achaea and Manfred of Sicily. Michael's ambitions were shattered however at the Battle of Pelagonia in 1259. In the aftermath of Pelagonia, even Epirus and Thessaly were for a short time occupied by the Nicaeans. More importantly, the victory opened the way for the Nicaean recapture of Constantinople on 15 August 1261, and the restoration of the Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty.[23][24]

Rulers

List of the Komnenos Doukas rulers of Thessalonica:

- Theodore Komnenos Doukas (1224–1230, crowned Emperor 1225/27)

- Manuel Komnenos Doukas (1230–1237, crowned Emperor 1235/37)

- John Komnenos Doukas (1237–1242 as Emperor; 1242–1244 as Despot)

- Demetrios Angelos Doukas (1244–1246 as Despot)

References

- e.g. Finlay 1877, pp. 124ff.,Vasiliev 1952, p. 522, Bartusis 1997, p. 23, Magdalino 1989, p. 87.

- Nicol 1993, pp. 8–12.

- Fine 1994, pp. 62–65.

- Nicol 1993, pp. 10–12.

- Hendy 1999, pp. 1, 6.

- Nicol 1993, pp. 12–13.

- Fine 1994, pp. 112–114, 119.

- Nicol 1993, pp. 13, 20.

- Fine 1994, pp. 119–120.

- Fine 1994, pp. 122–124.

- Fine 1994, pp. 124–125.

- Nicol 1993, pp. 13, 22.

- Fine 1994, pp. 125–126.

- Fine 1994, pp. 126–128.

- Fine 1994, p. 128.

- Nicol 1993, p. 22.

- Fine 1994, p. 133.

- Fine 1994, pp. 133–134.

- Fine 1994, p. 134.

- Fine 1994, p. 157.

- Fine 1994, p. 156.

- Fine 1994, pp. 157–158.

- Fine 1994, pp. 157–165.

- Nicol 1993, pp. 24, 28–29, 31–36.

Sources

- Bartusis, Mark C. (1997). The Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society 1204–1453. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1620-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Finlay, George (1877). A History of Greece: Mediaeval Greece and the empire of Trebizond, A.D. 1204–1461. Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hendy, Michael F. (1999). Catalogue of the Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and in the Whittemore Collection, Volume 4: Alexius I to Michael VIII, 1081–1261 – Part 1: Alexius I to Alexius V (1081–1204). Washington, District of Columbia: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 0-88402-233-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Magdalino, Paul (1989). "Between Romaniae: Thessaly and Epirus in the Later Middle Ages". In Arbel, Benjamin; Hamilton, Bernhard; Jacoby, David (eds.). Latins and Greeks in the Eastern Mediterranean After 1204. Frank Cass & Co. Ltd. pp. 87–110. ISBN 0-71463372-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993). The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453 (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43991-6.

- Vasiliev, Alexander A. (1952). History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-80926-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bredenkamp, François (1996). The Byzantine Empire of Thessaloniki (1224–1242). Thessaloniki: Thessaloniki History Center. ISBN 9608433177.

- Stavridou-Zafraka, Alkmini (1990). Νίκαια και Ήπειρος τον 13ο αιώνα. Ιδεολογική αντιπαράθεση στην προσπάθειά τους να ανακτήσουν την αυτοκρατορία [Nicaea and Epirus in the 13th century. Ideological confrontation in their effort to recover the empire] (in Greek). Thessaloniki.

- Stavridou-Zafraka, Alkmini (1992). "Η κοινωνία της Ηπείρου στο κράτος του Θεόδωρου Δούκα". Πρακτικά Διεθνούς Συμποσίου για το Δεσποτάτο της Ηπείρου (Άρτα, 27‐31 Μαΐου 1990) [The society of Epirus in the state of Theodore Doukas] (in Greek). Arta: Μουσικοφιλολογικός Σύλλογος Άρτης «Ο Σκουφάς». pp. 313–333.

- Stavridou-Zafraka, Alkmini (1999). "The Empire of Thessaloniki (1224–1242). Political Ideology and Reality". Vyzantiaka. 19: 211–222.