Vijayanagara Empire

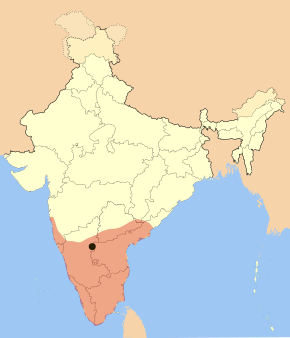

The Vijayanagara Empire (also called Karnata Empire,[3] and the Kingdom of Bisnegar by the Portuguese) was based in the Deccan Plateau region in South India. It was established in 1336 by the brothers Harihara I and Bukka Raya I of Sangama Dynasty,[4][5][6] members of a pastoralist cowherd community that claimed Yadava lineage.[7][8][9] The empire rose to prominence as a culmination of attempts by the southern powers to ward off Islamic invasions by the end of the 13th century. At its peak it had subjugated almost all of South Indias ruling families and the Sultans of the Deccan region thus becoming a notable power.[10] It lasted until 1646, although its power declined after a major military defeat in the Battle of Talikota in 1565 by the combined armies of the Deccan sultanates. The empire is named after its capital city of Vijayanagara, whose ruins surround present day Hampi, now a World Heritage Site in Karnataka, India.[11] The writings of medieval European travelers such as Domingo Paes, Fernão Nunes, and Niccolò Da Conti, and the literature in local languages provide crucial information about its history. Archaeological excavations at Vijayanagara have revealed the empire's power and wealth.

Vijayanagara Empire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1336–1646 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extent of Vijayanagara Empire, 1446, 1520 CE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Vijayanagara, Penukonda, Chandragiri[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Kannada, Sanskrit, Telugu[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1336–1356 | Harihara I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1642–1646 | Sriranga III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1336 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Earliest records | 1343 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1646 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Varaha | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vijayanagara Empire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of India |

Satavahana gateway at Sanchi, 1st century CE |

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

|

|

Early modern

|

|

Modern

|

|

Related articles

|

The empire's legacy includes many monuments spread over South India, the best known of which is the group at Hampi. Different temple building traditions in South and Central India came together in the Vijayanagara Architecture style. This synthesis inspired architectural innovation in Hindu temples' construction. Efficient administration and vigorous overseas trade brought new technologies such as water management systems for irrigation. The empire's patronage enabled fine arts and literature to reach new heights in Kannada, Telugu, Tamil, and Sanskrit, while Carnatic music evolved into its current form. The Vijayanagara Empire created an epoch in South Indian history that transcended regionalism by promoting Hinduism as a unifying factor.

Alternative name

Karnata Rajya (Karnata Empire) was another name for the Vijayanagara Empire, used in some inscriptions[12][13] and literary works of the Vijayanagara times including the Sanskrit work Jambavati Kalyanam by King Krishnadevaraya and Telugu work Vasu Charitamu.[14]

History

Differing theories have been proposed regarding the origins of the Vijayanagara empire. Many historians propose that Harihara I and Bukka I, the founders of the empire, were Kannadigas and commanders in the army of the Hoysala Empire stationed in the Tungabhadra region to ward off Muslim invasions from the Northern India.[15][16][17][18] Others claim that they were Telugu people, first associated with the Kakatiya Kingdom, who took control of the northern parts of the Hoysala Empire during its decline.[19] Irrespective of their origin, historians agree the founders were supported and inspired by Vidyaranya, a saint at the Sringeri monastery to fight the Muslim invasion of South India.[20][21] Writings by foreign travelers during the late medieval era combined with recent excavations in the Vijayanagara principality have uncovered much-needed information about the empire's history, fortifications, scientific developments and architectural innovations.[22][23]

Before the early 14th-century rise of the Vijayanagara Empire, the Hindu states of the Deccan – the Yadava Empire of Devagiri, the Kakatiya dynasty of Warangal, the Pandyan Empire of Madurai had been repeatedly raided and attacked by Muslims from the north, and by 1336 these upper Deccan region (modern day Maharashtra, Telangana) had all been defeated by armies of Sultan Alauddin Khalji and Muhammad bin Tughluq of the Delhi Sultanate.[20][24]

Further south in the Deccan region, a Hoysala commander, Singeya Nayaka-III (1280–1300 AD) declared independence after the Muslim forces of the Delhi Sultanate defeated and captured the territories of the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri in 1294 CE.[25][26] He created the Kampili kingdom, but this was a short lived kingdom during this period of wars.[25][27] Kampili existed near Gulbarga and Tungabhadra river in northeastern parts of the present-day Karnataka state.[27] It ended after a defeat by the armies of Delhi Sultanate. The triumphant army led by Malik Zada sent the news of its victory, over Kampili kingdom, to Muhammad bin Tughluq in Delhi by sending a straw-stuffed severed head of the dead Hindu king.[28] Within Kampili, on the day of certain defeat, the populace committed a jauhar (ritual mass suicide) in 1327/28 CE.[28][29] Eight years later, from the ruins of the Kampili kingdom emerged the Vijayanagara Kingdom in 1336 CE.[26]

In the first two decades after the founding of the empire, Harihara I gained control over most of the area south of the Tungabhadra river and earned the title of Purvapaschima Samudradhishavara ("master of the eastern and western seas"). By 1374 Bukka Raya I, successor to Harihara I, had defeated the chiefdom of Arcot, the Reddys of Kondavidu, and the Sultan of Madurai and had gained control over Goa in the west and the Tungabhadra-Krishna River doab in the north.[30][31] The original capital was in the principality of Anegondi on the northern banks of the Tungabhadra River in today's Karnataka. It was later moved to nearby Vijayanagara on the river's southern banks during the reign of Bukka Raya I, because it was easier to defend against the Muslim armies persistently attacking it from the northern lands.[32]

With the Vijayanagara Kingdom now imperial in stature, Harihara II, the second son of Bukka Raya I, further consolidated the kingdom beyond the Krishna River and brought the whole of South India under the Vijayanagara umbrella.[33] The next ruler, Deva Raya I, emerged successful against the Gajapatis of Odisha and undertook important works of fortification and irrigation.[34] Italian traveler Niccolo de Conti wrote of him as the most powerful ruler of India.[35] Deva Raya II (called Gajabetekara)[36] succeeded to the throne in 1424 and was possibly the most capable of the Sangama Dynasty rulers.[37] He quelled rebelling feudal lords as well as the Zamorin of Calicut and Quilon in the south. He invaded the island of Sri Lanka and became overlord of the kings of Burma at Pegu and Tanasserim.[38][39][40]

Firuz Bahmani of Bahmani Sultanate entered into a treaty with Deva Raya I of Vijayanagara in 1407 that required the latter to pay Bahmani an annual tribute of "100,000 huns, five maunds of pearls and fifty elephants". The Sultanate invaded Vijayanagara in 1417 when the latter defaulted in paying the tribute. Such wars for tribute payment by Vijayanagara repeated in the 15th century, such as in 1436 when Sultan Ahmad I launched a war to collect the unpaid tribute.[41]

The ensuing Sultanates-Vijayanagara wars expanded the Vijayanagara military, its power and disputes between its military commanders. In 1485, Saluva Narasimha led a coup and ended the dynastic rule, while continuing to defend the Empire from raids by the Sultanates created from the continuing disintegration of the Bahmani Sultanate in its north.[42] In 1505, another commander Tuluva Narasa Nayaka took over the Vijayanagara rule from the Saluva descendant in a coup. The empire came under the rule of Krishna Deva Raya in 1509, the son of Tuluva Narasa Nayaka.[43] He strengthened and consolidated the reach of the empire, by hiring both Hindus and Muslims into his army.[44] In the following decades, it covered Southern India and successfully defeated invasions from the five established Deccan Sultanates to its north.[45][46]

The empire reached its peak during the rule of Krishna Deva Raya when Vijayanagara armies were consistently victorious.[47][48] The empire gained territory formerly under the Sultanates in the northern Deccan and the territories in the eastern Deccan, including Kalinga, in addition to the already established presence in the south.[49] Many important monuments were either completed or commissioned during the time of Krishna Deva Raya.[50]

Krishna Deva Raya was followed by his younger half-brother Achyuta Deva Raya in 1529. When Achyuta Deva Raya died in 1542, Sadashiva Raya, the teenage nephew of Achyuta Raya was appointed king with the caretaker being Aliya Rama Raya, Krishna Deva Raya's son-in-law and someone who had previously served Sultan Quli Qutb al-Mulk from 1512 when al-Mulk was assigned to Golkonda sultanate.[51] Aliya Rama Raya left the Golconda Sultanate, married Deva Raya's daughter, and thus rose to power. When Sadashiva Raya – Deva Raya's son – was old enough, Aliya Rama Raya imprisoned him and allowed his uncle Achyuta Raya to publicly appear once a year.[52] Further Aliya Rama Raya hired Muslim generals in his army from his previous Sultanate connections, and called himself "Sultan of the World".[53]

The Sultanates to the north of Vijayanagara united and attacked Aliya Rama Raya's army, in January 1565, in a war known as the Battle of Talikota.[54] The Vijayanagara side was winning the war, state Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, but suddenly two Muslim generals of the Vijayanagara army switched sides and turned their loyalty to the Sultanates. The generals captured Aliya Rama Raya and beheaded him on the spot, with Sultan Hussain on the Sultanates side joining them for the execution and stuffing of severed head with straw for display.[55][56] The beheading of Aliya Rama Raya created confusion and havoc in the still loyal portions of the Vijayanagara army, which were then completely routed. The Sultanates' army plundered Hampi and reduced it to the ruinous state in which it remains; it was never re-occupied.[57]

After the death of Aliya Rama Raya in the Battle of Talikota, Tirumala Deva Raya started the Aravidu dynasty, moved and founded a new capital of Penukonda to replace the destroyed Hampi, and attempted to reconstitute the remains of Vijayanagara Empire.[58] Tirumala abdicated in 1572, dividing the remains of his kingdom to his three sons, and pursued a religious life until his death in 1578. The Aravidu dynasty successors ruled the region but the empire collapsed in 1614, and the final remains ended in 1646, from continued wars with the Bijapur sultanate and others.[59][60][61] During this period, more kingdoms in South India became independent and separate from Vijayanagara. These include the Mysore Kingdom, Keladi Nayaka, Nayaks of Madurai, Nayaks of Tanjore, Nayakas of Chitradurga and Nayak Kingdom of Gingee – all of which declared independence and went on to have a significant impact on the history of South India in the coming centuries.[62]

Governance

The rulers of the Vijayanagara empire maintained the well-functioning administrative methods developed by their predecessors, the Hoysala, Kakatiya and Pandya kingdoms, to govern their territories and made changes only where necessary.[63] The King (Svamin), ministry (Amatya), territory (Janapada), fort (Durga), treasury (Kosa), army (Daiufa), and ally (Mitra) formed the seven critical elements that influenced every aspect of governance.[64] The King was the ultimate authority, assisted by a cabinet of ministers (Pradhana) headed by the prime minister (Mahapradhana). Other important titles recorded were the chief secretary (Karyakartha or Rayaswami) and the imperial officers (Adhikari). All high-ranking ministers and officers were required to have military training.[65] A secretariat near the king's palace employed scribes and officers to maintain records made official by using a wax seal imprinted with the ring of the king.[66] At the lower administrative levels, wealthy feudal landlords (Goudas) supervised accountants (Karanikas or Karnam) and guards (Kavalu). The palace administration was divided into 72 departments (Niyogas), each having several female attendants chosen for their youth and beauty (some imported or captured in victorious battles) who were trained to handle minor administrative matters and to serve men of nobility as courtesans or concubines.[67]

The empire was divided into five main provinces (Rajya), each under a commander (Dandanayaka or Dandanatha) and headed by a governor, often from the royal family, who used the native language for administrative purposes.[68] A Rajya was divided into regions (Vishaya Vente or Kottam) and further divided into counties (Sime or Nadu), themselves subdivided into municipalities (Kampana or Sthala). Hereditary families ruled their respective territories and paid tribute to the empire, while some areas, such as Keladi and Madurai, came under the direct supervision of a commander.

On the battlefield, the king's commanders led the troops. The empire's war strategy rarely involved massive invasions; more often it employed small scale methods such as attacking and destroying individual forts. The empire was among the first in India to use long range artillery commonly manned by foreign gunners (those from present day Turkmenistan were considered the best).[69] Army troops were of two types: The king's personal army directly recruited by the empire and the feudal army under each feudatory. King Krishnadevaraya's personal army consisted of 100,000 infantry, 20,000 cavalrymen and over 900 elephants. This number was only a part of the army numbering over 1.1 million soldiers, a figure that varied as an army of two million has also been recorded along with the existence of a navy as evidenced by the use of the term Navigadaprabhu (commander of the navy).[70] The army recruited from all classes of society (supported by the collection of additional feudal tributes from feudatory rulers), and consisted of archers and musketeers wearing quilted tunics, shieldmen with swords and poignards in their girdles, and soldiers carrying shields so large that no armour was necessary. The horses and elephants were fully armoured and the elephants had knives fastened to their tusks to do maximum damage in battle.[71]

The capital city was completely dependent on the water supply systems constructed to channel and store water, ensuring a consistent supply throughout the year. The remains of these hydraulic systems have given historians a picture of the prevailing surface water distribution methods in use at that time in the semiarid regions of South India.[72] Contemporary records and notes of foreign travelers describe how huge tanks were constructed by labourers.[73] Excavations have uncovered the remains of a well-connected water distribution system existing solely within the royal enclosure and the large temple complexes (suggesting it was for the exclusive use of royalty, and for special ceremonies) with sophisticated channels using gravity and siphons to transport water through pipelines.[74] The only structures resembling public waterworks are the remains of large water tanks that collected the seasonal monsoon water and then dried up in summer except for the few fed by springs. In the fertile agricultural areas near the Tungabhadra River, canals were dug to guide the river water into irrigation tanks. These canals had sluices that were opened and closed to control the water flow. In other areas the administration encouraged the digging of wells monitored by administrative authorities. Large tanks in the capital city were constructed with royal patronage while smaller tanks were funded by wealthy individuals to gain social and religious merit.

Economy

The economy of the empire was largely dependent on agriculture. Sorghum (jowar), cotton, and pulse legumes grew in semi-arid regions, while sugarcane, rice, and wheat thrived in rainy areas. Betel leaves, areca (for chewing), and coconut were the principal cash crops, and large-scale cotton production supplied the weaving centers of the empire's vibrant textile industry. Spices such as turmeric, pepper, cardamom, and ginger grew in the remote Malnad hill region and were transported to the city for trade. The empire's capital city was a thriving business centre that included a burgeoning market in large quantities of precious gems and gold.[76] Prolific temple-building provided employment to thousands of masons, sculptors, and other skilled artisans.

Land ownership was important. Most of the growers were tenant farmers and were given the right of part ownership of the land over time. Tax policies encouraging needed produce made distinctions between land use to determine tax levies. For example, the daily market availability of rose petals was important for perfumers, so cultivation of roses received a lower tax assessment.[77] Salt production and the manufacture of salt pans were controlled by similar means. The making of ghee (clarified butter), which was sold as an oil for human consumption and as a fuel for lighting lamps, was profitable.[78] Exports to China intensified and included cotton, spices, jewels, semi-precious stones, ivory, rhino horn, ebony, amber, coral, and aromatic products such as perfumes. Large vessels from China made frequent visits, some captained by the Chinese Admiral Zheng He, and brought Chinese products to the empire's 300 ports, large and small, on the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. The ports of Mangalore, Honavar, Bhatkal, Barkur, Cochin, Cannanore, Machilipatnam, and Dharmadam were the most important.[79]

When merchant ships docked, the merchandise was taken into official custody and taxes levied on all items sold. The security of the merchandise was guaranteed by the administration officials. Traders of many nationalities (Arabs, Persians, Guzerates, Khorassanians) settled in Calicut, drawn by the thriving trade business.[79] Ship building prospered and keeled ships of 1000–1200 bahares (burden) were built without decks by sewing the entire hull with ropes rather than fastening them with nails. Ships sailed to the Red Sea ports of Aden and Mecca with Vijayanagara goods sold as far away as Venice. The empire's principal exports were pepper, ginger, cinnamon, cardamom, myrobalan, tamarind timber, anafistula, precious and semi-precious stones, pearls, musk, ambergris, rhubarb, aloe, cotton cloth and porcelain.[79] Cotton yarn was shipped to Burma and indigo to Persia. Chief imports from Palestine were copper, quicksilver (mercury), vermilion, coral, saffron, coloured velvets, rose water, knives, coloured camlets, gold and silver. Persian horses were imported to Cannanore before a two-week land trip to the capital. Silk arrived from China and sugar from Bengal.

East coast trade hummed, with goods arriving from Golkonda where rice, millet, pulses and tobacco were grown on a large scale. Dye crops of indigo and chay root were produced for the weaving industry. A mineral rich region, Machilipatnam was the gateway for high quality iron and steel exports. Diamond mining was active in the Kollur region.[80] The cotton weaving industry produced two types of cottons, plain calico and muslin (brown, bleached or dyed). Cloth printed with coloured patterns crafted by native techniques were exported to Java and the Far East. Golkonda specialised in plain cotton and Pulicat in printed. The main imports on the east coast were non-ferrous metals, camphor, porcelain, silk and luxury goods.[81]

Mahanavami festival marked the beginning of a financial year from when the state treasury accounted for and reconciled all outstanding dues within nine days. At this time, an updated annual assessment record of provincial dues, which included rents and taxes, paid on a monthly basis by each governor was created under royal decree.[64]

Temples were taxed for land ownership to cover military expenses. In the Telugu districts the temple tax was called Srotriyas, in the Tamil speaking districts it was called as Jodi. Taxes such as Durgavarthana, Dannayivarthana and Kavali Kanike were collected towards protection of movable and immovable wealth from robbery and invasions. Jeevadhanam was collected for cattle graze on non-private lands. Popular temple destinations charged visitor fees called Perayam or Kanike. Residential property taxes were called Illari.[82]

Culture

Social life

Most information on the social life in the empire comes from the writings of foreign visitors and evidence that research teams in the Vijayanagara area have uncovered. The Hindu caste system was prevalent. Caste was determined by either an individuals occupation or the professional community they belonged to (Varnashrama).[64] The number of castes had multiplied into several sub-castes and community groups[64] Each community was represented by a local body of elders who set the rules that were implemented with the help of royal decrees. Marked evolution of social solidarity can be observed in the community as they vied for privileges and honors and developed unique laws and customs.[64] Health and hygiene by bathing daily was important among certain sections of Hindus and so was oiling ones head at least every fortnight.[83] The practice of Untouchability existed perhaps stemming from the consumption of poor quality meat by persons belonging to the lowest strata of society.[83] Muslim communities had their own representatives in coastal Karnataka.[84] The caste system did not however prevent distinguished persons from all castes from being promoted to high-ranking cadre in the army and administration, such as the Veerashaiva who played a key role in the capture of a Sultanate fortress at Gulbarga.[85] In civil life, Brahmins commanded a high level of respect as they lived for their duty and led a simple life. While most discharged priestly duties in temples and monasteries some were land owners, politicians, administrators and generals.[86] Their separation from material wealth and power made them ideal arbiters in local judicial matters, and their presence in every town and village was a calculated investment made by the nobility and aristocracy to maintain order.[87] However, the popularity of other caste scholars and their writings such as those by Molla, Kanakadasa, Vemana and Sarvajna is an indication of the degree of social fluidity in the society. Gaudas were the village chiefs.[64] The Gauda chief of Yelahanka village, Hiriya Kempe I, is considered the founder of Bangalore city.[88]

Sati practice is evidenced in Vijayanagara ruins by several inscriptions known as Satikal (Sati stone) or Sati-virakal (Sati hero stone).[90] There are controversial views among historians regarding this practice including religious compulsion, marital affection, martyrdom or honor against subjugation by foreign intruders.[91][64][92][93]

The socio-religious movements that gained popularity in the previous centuries, such as Lingayatism, provided momentum for flexible social norms that helped the cause of women. By this time South Indian women had crossed most barriers and were actively involved in fields hitherto considered the monopoly of men such as administration, business, trade and the fine arts.[94] Tirumalamba Devi who wrote Varadambika Parinayam and Gangadevi the author of Madhuravijayam were among the notable women poets of the Sanskrit language.[30] Early Telugu women poets such as Tallapaka Timmakka and Atukuri Molla became popular. Further south the provincial Nayaks of Tanjore patronised several women poets. The Devadasi system as well as legalized prostitution existed and members of this community were relegated to a few streets in each city. The popularity of harems among men of the royalty and the existence of seraglio is well known from records.[95]

Well-to-do men wore the Petha or Kulavi, a tall turban made of silk and decorated with gold. As in most Indian societies, jewellery was used by men and women and records describe the use of anklets, bracelets, finger-rings, necklaces and ear rings of various types. During celebrations men and women adorned themselves with flower garlands and used perfumes made of rose water, civet musk, musk or sandalwood.[95] In stark contrast to the commoners whose lives were modest, that of the king and the queens were full of ceremonial pomp. Queens and princesses had numerous attendants who were lavishly dressed and adorned with fine jewellery. The numbers ensured their daily duties were light.[96]

Physical exercises were popular with men and wrestling was an important male preoccupation for sport and entertainment. Even women wrestlers are mentioned in records.[84] Gymnasiums have been discovered inside royal quarters and records mention regular physical training for commanders and their armies during peacetime.[97] Royal palaces and market places had special arenas where royalty and common people alike amused themselves by watching sports such as cock fight, ram fight and female wrestling.[97] Excavations within the Vijayanagara city limits have revealed the existence of various types of community-based gaming activities. Engravings on boulders, rock platforms and temple floors indicate these were popular locations of casual social interaction. Some of these games are in use even today and others are yet to be identified.[98]

Dowry was in practice and can be seen in both Hindu and Muslim royal families of the time. When a sister of Sultan Adil Shah of Bijapur was married to Nizam Shah of Ahmednagar the town of Sholapur was given to the bride by her family.[99] Ayyangar notes that when the Gajapati King of Kalinga gave his daughter in marriage honoring the victorious King Krishnadevaraya he included several villages as dowry.[100] Inscriptions of the 15th and 16th centuries record the practice of dowry among commoners as well. The practice of putting a price on the bride was a possible influence of the Islamic Mahr system.[101] To oppose this influence, in the year 1553, the Brahmin community passed a mandate under royal decree and popularized the kanyadana within the community. According to this practice money could not be paid or received during marriage and those who did were liable for punishment. There is a mention of Streedhana ("woman's wealth") in an inscription and that the villagers should not give away land as dowry. These inscriptions reinforce the theory that a system of social mandates within community groups existed and were widely practiced even though these practices did not find justification in the family laws described in the religious texts.[102]

Religion

The Vijayanagara kings were tolerant of all religions and sects, as writings by foreign visitors show.[103] The kings used titles such as Gobrahamana Pratipalanacharya (literally, "protector of cows and Brahmins") and Hindurayasuratrana (lit, "upholder of Hindu faith") that testified to their intention of protecting Hinduism and yet were at the same time staunchly Islamicate in their court ceremonials and dress.[104] The empire's founders, the Sangama brothers (Harihara I and Bukka Raya I) came from a pastoral cowherd background (the Kuruba people) that claimed Yadava lineage.[7] They were devout Shaivas (worshippers of Shiva) but made grants to the Vaishnava order of Sringeri with Vidyaranya as their patron saint, and designated Varaha (the boar, an Avatar of Vishnu) as their emblem.[105] Over one-fourth of the archaeological dig found an "Islamic Quarter" not far from the "Royal Quarter". Nobles from Central Asia's Timurid kingdoms also came to Vijayanagara. The later Saluva and Tuluva kings were Vaishnava by faith, but worshipped at the feet of Lord Virupaksha (Shiva) at Hampi as well as Lord Venkateshwara (Vishnu) at Tirupati. A Sanskrit work, Jambavati Kalyanam by King Krishnadevaraya, refers to Lord Virupaksha as Karnata Rajya Raksha Mani ("protective jewel of Karnata Empire").[106] The kings patronised the saints of the dvaita order (philosophy of dualism) of Madhvacharya at Udupi.[107] Endowments were made to temples in the form of land, cash, produce, jewellery and constructions.[108]

The Bhakti (devotional) movement was active during this time, and involved well known Haridasas (devotee saints) of that time. Like the Virashaiva movement of the 12th century, this movement presented another strong current of devotion, pervading the lives of millions. The haridasas represented two groups, the Vyasakuta and Dasakuta, the former being required to be proficient in the Vedas, Upanishads and other Darshanas, while the Dasakuta merely conveyed the message of Madhvacharya through the Kannada language to the people in the form of devotional songs (Devaranamas and Kirthanas). The philosophy of Madhvacharya was spread by eminent disciples such as Naraharitirtha, Jayatirtha, Sripadaraya, Vyasatirtha, Vadirajatirtha and others.[109] Vyasatirtha, the guru (teacher) of Vadirajatirtha, Purandaradasa (Father of Carnatic music[110][111]) and Kanakadasa[112] earned the devotion of King Krishnadevaraya.[113][114][115] The king considered the saint his Kuladevata (family deity) and honoured him in his writings.[116] During this time, another great composer of early carnatic music, Annamacharya composed hundreds of Kirthanas in Telugu at Tirupati in present-day Andhra Pradesh.[117]

The defeat of the Jain Western Ganga Dynasty by the Cholas in the early 11th century and the rising numbers of followers of Vaishnava Hinduism and Virashaivism in the 12th century was mirrored by a decreased interest in Jainism.[118] Two notable locations of Jain worship in the Vijayanagara territory were Shravanabelagola and Kambadahalli.

Islamic contact with South India began as early as the 7th century, a result of trade between the Southern kingdoms and Arab lands. Jumma Masjids existed in the Rashtrakuta empire by the 10th century[119] and many mosques flourished on the Malabar coast by the early 14th century.[120] Muslim settlers married local women; their children were known as Mappillas (Moplahs) and were actively involved in horse trading and manning shipping fleets. The interactions between the Vijayanagara empire and the Bahamani Sultanates to the north increased the presence of Muslims in the south. In the early 15th century, Deva Raya built a mosque for the Muslims in Vijayanagara and placed a Quran before his throne.[121] The introduction of Christianity began as early as the 8th century as shown by the finding of copper plates inscribed with land grants to Malabar Christians. Christian travelers wrote of the scarcity of Christians in South India in the Middle Ages, promoting its attractiveness to missionaries.[122] The arrival of the Portuguese in the 15th century and their connections through trade with the empire, the propagation of the faith by Saint Xavier (1545) and later the presence of Dutch settlements fostered the growth of Christianity in the south.

Language

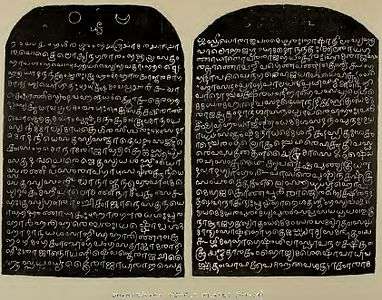

Kannada, Telugu and Tamil were used in their respective regions of the empire. Over 7000 inscriptions (Shilashasana) including 300 copper plate inscriptions (Tamarashasana) have been recovered, almost half of which are in Kannada, the remaining in Telugu, Tamil and Sanskrit.[123][124][125] Bilingual inscriptions had lost favour by the 14th century.[126] The empire minted coins at Hampi, Penugonda and Tirupati with Nagari, Kannada and Telugu legends usually carrying the name of the ruler.[127][128] Gold, silver and copper were used to issue coins called Gadyana, Varaha, Pon, Pagoda, Pratapa, Pana, Kasu and Jital.[129] The coins contained the images of various gods including Balakrishna (infant Krishna), Venkateshwara (the presiding deity of the temple at Tirupati), goddesses such as Bhudevi and Sridevi, divine couples, animals such as bulls and elephants and birds. The earliest coins feature Hanuman and Garuda (divine eagle), the vehicle of Lord Vishnu.

Kannada and Telugu inscriptions have been deciphered and recorded by historians of the Archaeological Survey of India.[130][131]

Literature

During the rule of the Vijayanagara Empire, poets, scholars and philosophers wrote primarily in Kannada, Telugu and Sanskrit, and also in other regional languages such as Tamil and covered such subjects as religion, biography, Prabandha (fiction), music, grammar, poetry, medicine and mathematics. The administrative and court languages of the Empire were Kannada and Telugu—the latter was the court language and gained even more cultural prominence during the reign of the last Vijayanagara kings.[132][133][134] Telugu was a popular literary medium, reaching its peak under the patronage of Krishnadevaraya.[133]

Most Sanskrit works were commentaries either on the Vedas or on the Ramayana and Mahabharata epics, written by well known figures such as Sayanacharya (who wrote a treatise on the Vedas called Vedartha Prakasha whose English translation by Max Muller appeared in 1856), and Vidyaranya that extolled the superiority of the Advaita philosophy over other rival Hindu philosophies.[135] Other writers were famous Dvaita saints of the Udupi order such as Jayatirtha (earning the title Tikacharya for his polemicial writings), Vyasatirtha who wrote rebuttals to the Advaita philosophy and of the conclusions of earlier logicians, and Vadirajatirtha and Sripadaraya both of whom criticized the beliefs of Adi Sankara.[115] Apart from these saints, noted Sanskrit scholars adorned the courts of the Vijayanagara kings and their feudal chiefs. Some members of the royal family were writers of merit and authored important works such as Jambavati Kalyana by King Krishnadevaraya,[14] and Madura Vijayam by Princess Gangadevi, a daughter-in-law of King Bukka I. Also known as Veerakamparaya Charita, the book dwells on the conquest of the Madurai Sultanate by the Vijayanagara empire.[136]

The Kannada poets and scholars of the empire produced important writings supporting the Vaishnava Bhakti movement heralded by the Haridasas (devotees of Vishnu), Brahminical and Veerashaiva (Lingayatism) literature. The Haridasa poets celebrated their devotion through songs called Devaranama (lyrical poems) in the native meters of Sangatya (quatrain), Suladi (beat based), Ugabhoga (melody based) and Mundige (cryptic).[137] Their inspirations were the teachings of Madhvacharya and Vyasatirtha. Purandaradasa and Kanakadasa are considered the foremost among many Dasas (devotees) by virtue of their immense contribution.[138] Kumara Vyasa, the most notable of Brahmin scholars wrote Gadugina Bharata, a translation of the epic Mahabharata. This work marks a transition of Kannada literature from old Kannada to modern Kannada.[139] Chamarasa was a famous Veerashaiva scholar and poet who had many debates with Vaishnava scholars in the court of Devaraya II. His Prabhulinga Leele, later translated into Telugu and Tamil, was a eulogy of Saint Allama Prabhu (the saint was considered an incarnation of Lord Ganapathi while Parvati took the form of a princess of Banavasi).[140][141]

At this peak of Telugu literature, the most famous writing in the Prabandha style was Manucharitamu. King Krishnadevaraya was an accomplished Telugu scholar and wrote the celebrated Amuktamalyada.[142] Amuktamalyada ("One who wears and gives away garlands") narrates the story of the wedding of the god Vishnu to Andal, the Tamil Alvar saint poet and the daughter of Periyalvar at Srirangam.[143][144][145] In his court were eight famous scholars regarded as the pillars (Ashtadiggajas) of the literary assembly. The most famous among them were Allasani Peddana who held the honorific Andhrakavitapitamaha (lit, "father of Telugu poetry") and Tenali Ramakrishna, the court jester who authored several notable works.[146] The other six poets were Nandi Thimmana (Mukku Timmana), Ayyalaraju Ramabhadra, Madayyagari Mallana, Bhattu Murthi (Ramaraja Bhushana), Pingali Surana, and Dhurjati. This was the age of Srinatha, the greatest of all Telugu poets of the time. He wrote books such as Marutratcharitamu and Salivahana-sapta-sati. He was patronised by King Devaraya II and enjoyed the same status as important ministers in the court.[147]

Though much of the Tamil literature from this period came from Tamil speaking regions ruled by the feudatory Pandya who gave particular attention on the cultivation of Tamil literature, some poets were patronised by the Vijayanagara kings. Svarupananda Desikar wrote an anthology of 2824 verses, Sivaprakasap-perundirattu, on the Advaita philosophy. His pupil the ascetic, Tattuvarayar, wrote a shorter anthology, Kurundirattu, that contained about half the number of verses. Krishnadevaraya patronised the Tamil Vaishnava poet Haridasa whose Irusamaya Vilakkam was an exposition of the two Hindu systems, Vaishnava and Shaiva, with a preference for the former.[148]

Notable among secular writings on music and medicine were Vidyaranya's Sangitsara, Praudha Raya's Ratiratnapradipika, Sayana's Ayurveda Sudhanidhi and Lakshmana Pandita's Vaidyarajavallabham.[149] The Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics flourished during this period under such well known scholars as Madhava (c. 1340–1425) who made important contributions to Trigonometery and Calculus, and Nilakantha Somayaji (c. 1444–1545) who postulated on the orbitals of planets.[150]

Architecture

Vijayanagara architecture is a vibrant combination of the Chalukya, Hoysala, Pandya and Chola styles, idioms that prospered in previous centuries.[151][152] Its legacy of sculpture, architecture and painting influenced the development of the arts long after the empire came to an end. Its stylistic hallmark is the ornate pillared Kalyanamantapa (marriage hall), Vasanthamantapa (open pillared halls) and the Rayagopura (tower). Artisans used the locally available hard granite because of its durability since the kingdom was under constant threat of invasion. While the empire's monuments are spread over the whole of Southern India, nothing surpasses the vast open-air theatre of monuments at its capital at Vijayanagara, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[153]

In the 14th century the kings continued to build vesara or Deccan-style monuments but later incorporated Dravida-style gopuras to meet their ritualistic needs. The Prasanna Virupaksha temple (underground temple) of Bukka and the Hazare Rama temple of Deva Raya are examples of Deccan architecture.[154] The varied and intricate ornamentation of the pillars is a mark of their work.[155] At Hampi, though the Vitthala temple is the best example of their pillared Kalyanamantapa style, the Hazara Ramaswamy temple is a modest but perfectly finished example.[156] A visible aspect of their style is their return to the simplistic and serene art developed by the Chalukya dynasty.[157] A grand specimen of Vijayanagara art, the Vitthala temple, took several decades to complete during the reign of the Tuluva kings.[158]

Another element of the Vijayanagara style is the carving and consecration of large monoliths such as the Sasivekaalu (mustard) Ganesha and Kadalekaalu (ground nut) Ganesha at Hampi, the Gommateshwara (Bahubali) monoliths in Karkala and Venur, and the Nandi bull in Lepakshi. The Vijayanagara temples of Kolar, Kanakagiri, Sringeri and other towns of Karnataka; the temples of Tadpatri, Lepakshi, Ahobilam, Tirumala Venkateswara Temple and Srikalahasti in Andhra Pradesh; and the temples of Vellore, Kumbakonam, Kanchi and Srirangam in Tamil Nadu are examples of this style. Vijayanagara art includes wall-paintings such as the Dashavatara and Girijakalyana (marriage of Parvati, Shiva's consort) in the Virupaksha Temple at Hampi, the Shivapurana murals (tales of Shiva) at the Virabhadra temple at Lepakshi, and those at the Kamaakshi and Varadaraja temples at Kanchi.[159] This mingling of the South Indian styles resulted in a richness not seen in earlier centuries, a focus on reliefs in addition to sculpture that surpasses that previously in India.[160]

An aspect of Vijayanagara architecture that shows the cosmopolitanism of the great city is the presence of many secular structures bearing Islamic features. While political history concentrates on the ongoing conflict between the Vijayanagara empire and the Deccan Sultanates, the architectural record reflects a more creative interaction. There are many arches, domes and vaults that show these influences. The concentration of structures like pavilions, stables and towers suggests they were for use by royalty.[161] The decorative details of these structures may have been absorbed into Vijayanagara architecture during the early 15th century, coinciding with the rule of Deva Raya I and Deva Raya II. These kings are known to have employed many Muslims in their army and court, some of whom may have been Muslim architects. This harmonious exchange of architectural ideas must have happened during rare periods of peace between the Hindu and Muslim kingdoms.[162] The "Great Platform" (Mahanavami Dibba) has relief carvings in which the figures seem to have the facial features of central Asian Turks who were known to have been employed as royal attendants.[163]

See also

Notes

- Howes, Jennifer (1998). The Courts of Pre-colonial South India: Material Culture and Kingship. Psychology Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-07-0071-585-5.

- Bridges, Elizabeth J. (2016). "Vijayanagara Empire". In Dalziel, N.; MacKenzie, J. M. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Empire. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe424. ISBN 9781118455074.

- Stein 1989, p. 1.

- Longworth, James Mansel (1921), p.204, The Book of Duarte Barbose, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, ISBN 81-206-0451-2

- J C Morris (1882), p.261, The Madras Journal Of Literature and Science, Madras Literary Society, Madras, Graves Cookson & Co.

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 103–106. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4.

- Dhere, Ramachandra Chintaman (2011). Rise of a Folk God: Vitthal of Pandharpur. Oxford University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-19977-764-8.

- Lewis, Rice B (1897). Mysore: A gazetteer compiled for government, vol 1. Mysore: Archibald Constable & Co. p. 345.

- Sastri, Nilakanta (1935). K. A. Nilakanta Sastri Books: Further Source of Vijayanagara History Volume 1. p. 23.

- Stein, Burton (1989). The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. XI.

- "Master Plan for Hampi Local Planning Area" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2013.

- K.V.Ramesh. "Telugu Inscriptions from Vijayanagar Dynasty, vol16, Introduction". Archaeological Survey of India. What Is India Publishers (P) Ltd., Saturday, December 30, 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 268

- Fritz & Michell 2001, p. 14

- Historians such as P. B. Desai (History of Vijayanagar Empire, 1936), Henry Heras (The Aravidu Dynasty of Vijayanagara, 1927), B.A. Saletore (Social and Political Life in the Vijayanagara Empire, 1930), G.S. Gai (Archaeological Survey of India), William Coelho (The Hoysala Vamsa, 1955) and Kamath (Kamath 2001, pp. 157–160)

- Karmarkar (1947), p30

- Kulke and Rothermund (2004), p188

- Rice (1897), p345

- Sewell 1901; Nilakanta Sastri 1955; N. Ventakaramanayya, The Early Muslim expansion in South India, 1942; B. Surya Narayana Rao, History of Vijayanagar, 1993; Kamath 2001, pp. 157–160

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 216

- Kamath 2001, p. 160

- Portuguese travelers Barbosa, Barradas and Italian Varthema and Caesar Fredericci in 1567, Persian Abdur Razzak in 1440, Barani, Isamy, Tabataba, Nizamuddin Bakshi, Ferishta and Shirazi and vernacular works from the 14th century to the 16th century. (Kamath 2001, pp. 157–158)

- Fritz & Michell 2001, pp. 1–11

- VA Smith. The Oxford History of India. Clarendon: Oxford University Press. pp. 275–298.

- Burton Stein (1989). The New Cambridge History of India: Vijayanagara. Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-521-26693-2.

- David Gilmartin; Bruce B. Lawrence (2000). Beyond Turk and Hindu: Rethinking Religious Identities in Islamicate South Asia. University Press of Florida. pp. 300–306, 321–322. ISBN 978-0-8130-3099-9.

- Cynthia Talbot (2001). Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra. Oxford University Press. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-19-803123-9.

- Mary Storm (2015). Head and Heart: Valour and Self-Sacrifice in the Art of India. Taylor & Francis. p. 311. ISBN 978-1-317-32556-7.

- Kanhaiya L Srivastava (1980). The position of Hindus under the Delhi Sultanate, 1206-1526. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 202.

- Kamath 2001, p. 162

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 317

- VA Smith. The Oxford History of India. Clarendon: Oxford University Press. pp. 299–302.

- The success was probably also due to the peaceful nature of Muhammad II Bahmani, according to Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 242

- From the notes of Portuguese Nuniz. Robert Sewell notes that a big dam across was built the Tungabhadra and an aqueduct 15 miles (24 km) long was cut out of rock (Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 243).

- Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture, John Stewart Bowman p.271, (2013), Columbia University Press, New York, ISBN 0-231-11004-9

- Also deciphered as Gajaventekara, a metaphor for "great hunter of his enemies", or "hunter of elephants" ((Kamath 2001, p. 163)).

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 244

- From the notes of Persian Abdur Razzak. Writings of Nuniz confirms that the kings of Burma paid tributes to Vijayanagara empire Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 245

- Kamath 2001, p. 164

- From the notes of Abdur Razzak about Vijayanagara: a city like this had not been seen by the pupil of the eye nor had an ear heard of anything equal to it in the world (Hampi, A Travel Guide 2003, p11)

- Eaton 2006, pp. 89–90 with footnote 28.

- Eaton 2006, pp. 86–87.

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 250

- Eaton 2006, pp. 87–88.

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 239

- Kamath 2001, p. 159

- From the notes of Portuguese traveler Domingo Paes about Krishna Deva Raya: A king who was perfect in all things (Hampi, A Travel Guide 2003, p31)

- Eaton 2006, pp. 88–89.

- The notes of Portuguese Barbosa during the time of Krishna Deva Raya confirms a very rich and well provided Vijayanagara city ((Kamath 2001, p. 186))

- Most monuments including the royal platform (Mahanavami Dibba) were actually built over a period spanning several decades (Dallapiccola 2001, p66)

- Eaton 2006, p. 79, Quote: "Rama Raya first appears in recorded history in 1512, when Sultan Quli Qutb al-Mulk enrolled this Telugu warrior as a military commander and holder of a land assignment in the newly emerged sultanate of Golkonda.".

- Eaton 2006, p. 92.

- Eaton 2006, pp. 93–101.

- Eaton 2006, pp. 96–98.

- Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0., Quote: "When battle was joined in January 1565, it seemed to be turning in favor of Vijayanagara - suddenly, however, two Muslim generals of Vijayanagara changes sides. Rama Raya was taken prisoner and immediately beheaded."

- Eaton 2006, pp. 98, Quote: "Husain (...) ordered him beheaded on the spot, and his head stuffed with straw (for display).".

- Eaton 2006, pp. 98–101.

- Eaton 2006, pp. 100–101.

- Kamath 2001, p. 174

- Vijaya Ramaswamy (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Tamils. Scarecrow Press. pp. Li–Lii. ISBN 978-0-8108-6445-0.

- Eaton 2006, pp. 101-115.

- Kamath 2001, pp. 220, 226, 234

- A war administration, (K.M. Panikkar in Kamath 2001, p. 174

- Mahalingam, T.V (1940). Administration and social life under Vijayanagara. Madras University Historical Series, No. 15. University of Madras. pp. 9, 101, 160, 239, 244, 246, 260.

- From the notes of Persian Abdur Razzak and research by B.A. Saletore ((Kamath 2001, p. 175))

- From the notes of Nuniz ((Kamath 2001, p. 175))

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 286

- From the notes of Duarte Barbosa ((Kamath 2001, p. 176)). However, the kingdom may have had nine provinces (T. V. Mahalingam in Kamath 2001, p. 176

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 287

- From the notes of Abdur Razzaq and Paes respectively ((Kamath 2001, p. 176))

- From the notes of Nuniz Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 288

- Davison-Jenkins (2001), p89

- From the notes of Domingo Paes and Nuniz (Davison-Jenkins 2001, p98)

- Davison-Jenkins (2001), p90

- "Vijayanagara Research Project::Elephant Stables". Vijayanagara.org. 9 February 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- From the notes of Duarte Barbosa ((Kamath 2001, p. 181)).

- From the notes of Abdur Razzak in Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 298

- From the notes of Abdur Razzak in Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 299

- From the notes of Abdur Razzak in Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 304

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 305

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 306

- Reddy, Soma. "Taxation of Hindu Temples in the Telugu districts of the Vijayanagara Empire". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 39: 503–508. JSTOR 44139388.

- Moreland, W.H (1931). Relation of Golconda in the Early Seventeenth Century. Halyukt Society. pp. 70, 78. ISBN 978-1-4094-1433-9.

- Kamath 2001, p. 179

- Burton, Stein (1989). The New Cambridge History of India: Vijayanagara. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-521-26693-2.

- T.V, MAHALINGAM (1940). Administration and social life under Vijayanagara. University of Madras. pp. 240–242.

- According to Sir Charles Elliot, the intellectual superiority of Brahmins justified their high position in society (Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 289)

- George, Michell (1998). Architecture and Art of Southern India: Vijayanagara and the Successor States 1350-1750. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9781139055642.

- Rice, Benjamin Lewis (1894). Epigraphia Carnatica: Volume IX: Inscriptions in the Bangalore District. Mysore State, British India: Mysore Department of Archaeology. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Verghese (2001), p 41

- John Stratton Hawley (1994). Sati, the Blessing and the Curse: The Burning of Wives in India. Oxford University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0-19-536022-6.

- Lindsey, Harlan, Professor of Religious Studies (2018). Religion and Rajput Women: The Ethic of Protection in Contemporary Narratives. University of California Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780520301757.

- H.G, Rekha (2019). "Sati Memorial Stones of Vijayanagara Period - A Study". History Research Journal. 5 (6): 2110.

- B.A. Saletore in Kamath 2001, p. 179

- Kamath 2001, p. 180

- From the writings of Portuguese Domingo Paes (Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 296)

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 296

- Mack (2001), p39

- Babu, Dr.M.Bosu (2018). Material Background to the Vijayanagara Empire (A Study with Special reference To Southern Āndhradēśa From A.D. 1300 To 1500). K.Y.Publications. p. 189. ISBN 978-9387769427.

- >Ayyangar, Krishnaswami (2019). Sources of Vijayanagar History. Alpha Editions. p. 116. ISBN 978-9353605902.

- Dr.B. S. Chandrababu, and Dr.L. Thilagavathi (2009). Woman, Her History and Her Struggle for Emancipation. Bharathi Puthakalayam. p. 266. ISBN 9788189909970.

- Mahalingam, T.V (1940). Administration and Social Life under Vijayanagar. Madras: University of Madras Historical Series No.15. pp. 255–256.

- From the notes of Duarte Barbosa ((Kamath 2001, p. 178))

- Wagoner, Phillip B. (November 1996). "Sultan among Hindu Kings: Dress, Titles, and the Islamicization of Hindu Culture at Vijayanagara". The Journal of Asian Studies. 55 (4): 851–880. doi:10.2307/2646526. JSTOR 2646526.

- Kamath 2001, p. 177

- Fritz & Michell 2001, p. 14

- Kamath 2001, pp. 177–178

- Naik, Reddy, Krishna, Ramajulu (2007). "Impact of endowments on society during the Vijayanagara period: A study of the Rayalaseema region, 1336-1556". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 68: 286–294. JSTOR 44147838.

- Shiva Prakash in Ayyappapanicker (1997), p192, pp194–196

- Iyer (2006), p93

- Owing to his contributions to carnatic music, Purandaradasa is known as Karnataka Sangita Pitamaha. (Kamat, Saint Purandaradasa)

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p196

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p195

- Kamath 2001, p. 178

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 324

- Pujar, Narahari S.; Shrisha Rao; H.P. Raghunandan. "Sri Vyasa Tirtha". Dvaita Home Page. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- Kamath 2001, p. 185

- Kamath 2001, pp. 112, 132

- From the notes of Arab writer Al-Ishtakhri (Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 396)

- From the notes of Ibn Batuta (Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 396)

- Lewis, Rice B (1897). Mysore: A gazetteer compiled for government, vol 1. Mysore: Archibald Constable & Co. p. 479.

- From the notes of Jordanus in 1320–21 (Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 397)

- G.S. Gai in Kamath 2001, pp. 10, 157

- Arthikaje, Mangalore. "The Vijayanagar Empire". 1998–2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- Subbarayalu, Y; Rajavelu, S, eds. (2015). Inscriptions of the Vijayanagara Rulers: Volume V, Part 1 (Tamil Inscriptions). New Delhi: Indian Council of Historical Research. ISBN 978-9380607757.

- Thapar (2003), pp 393–95

- "Vijayanagara Coins". Government Museum Chennai. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- Prabhu, Govindaraya S. "Catalogue, Part one". Vijayanagara, the forgotten empire. Prabhu's Web Page on Indian Coinage. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- Harihariah Oruganti. "Coinage". Catalogue. Vijayanagara Coins. Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- Ramesh, K. V. "Stones 1–25". South Indian Inscription, Volume 16: Telugu Inscriptions from Vijayanagar Dynasty. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

- Sastry & Rao, Shama & Lakshminarayan. "Miscellaneous Inscriptions, Part II". South Indian Inscription, Volume 9: Kannada Inscriptions from Madras Presidency. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

- Pollock, Sheldon; Pollock, Arvind Raghunathan Professor of South Asian Studies Sheldon (19 May 2003). Pollock, Sheldon. ISBN 9780520228214. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

Quote:"Telugu had certainly been more privileged than Kannada as a language of courtly culture during the reign of the last Vijayanagara kings, especially Krsnadevaraya (d.1529)

, Nagaraj in Pollock (2003), p378 - Quote:"Royal patronage was also directed to the support of literature in several languages: Sanskrit (the pan-Indian literary language), Kannada (the language of the Vijayanagara home base in Karnataka), and Telugu (the language of Andhra). Works in all three languages were produced by poets assembled at the courts of the Vijayanagara kings". Quote:"The Telugu language became particularly prominent in the ruling circles by the early 16th century, because of the large number of warrior lords who were either from Andhra or had served the kingdom there", Asher and Talbot (2006), pp 74–75

- "Telugu Literature". Retrieved 19 July 2013.

Telugu literature flowered in the early 16th century under the Vijayanagara empire, of which Telugu was the court language.

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 321

- Devi, Ganga (1924). Sastri, G Harihara; Sastri, V Srinivasa (eds.). Madhura Vijaya (or Veerakamparaya Charita): An Historical Kavya. Trivandrum, British India: Sridhara Power Press. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- Shiva Prakash in Ayyappapanicker (1997), p164, pp 193–194, p203

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 365

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 364

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 363

- Rice E.P. (1921), p.68

- During the rule of Krishnadevaraya, encouragement was given to the creation of original Prabandhas (stories) from Puranic themes (Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 372)

- Rao, Pappu Venugopala (22 June 2010). "A masterpiece in Telugu literature" (Chennai). The Hindu. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Krishnadevaraya (2010). Reddy, Srinivas (ed.). Giver of the Worn Garland: Krishnadevaraya's Amuktamalyada. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-8184753059. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Krishnadevaraya (1907). Amuktamalyada. London: Telugu Collection for the British Library. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Like the nine gems of King Vikramaditya's court, the Ashtadiggajas were famous during the 16th century.(Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 372)

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 370

- Nilakanta Sastri 1955, p. 347

- Prasad (1988), pp.268–270

- "History of Science and Philosophy of Science: A Historical Perspective of the Evolution of Ideas in Science", editor: Pradip Kumar Sengupta, author: Subhash Kak, 2010, p91, vol XIII, part 6, Publisher: Pearson Longman, ISBN 978-81-317-1930-5

- Art critic Percy Brown calls Vijayanagara architecture a blossoming of Dravidian style ((Kamath 2001, p. 182))

- Arthikaje, Literary Activity, Art and Architecture, History of karnataka. OurKarnataka.Com

- "So intimate are the rocks and the monuments they were used for make, it was sometimes impossible to say where nature ended and art began" (Art critic Percy Brown, quoted in Hampi, A Travel Guide, p64)

- Fritz & Michell 2001, p. 9

- Nilakanta Sastri about the importance of pillars in the Vijayanagar style in Kamath 2001, p. 183

- "Drama in stone" wrote art critic Percy Brown, much of the beauty of Vijayanagara architecture came from their pillars and piers and the styles of sculpting (Hampi, A Travel Guide, p77)

- About the sculptures in Vijayanagara style, see Kamath 2001, p. 184

- Several monuments are categorised as Tuluva art (Fritz & Michell 2001, p. 9)

- Some of these paintings may have been redone in later centuries (Rajashekhar in Kamath 2001, p. 184)

- Historians and art critics K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, A. L. Basham, James Fergusson and S. K. Saraswathi have commented about Vijayanagara architecture (Arthikaje Literary Activity).

- Fritz & Michell 2001, p. 10

- Philon (2001), p87

- Dallapiccola (2001), p69

Bibliography

- Arthikaje. "Literary Activity, Art and Architecture". History of karnataka. OurKarnataka.Com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 31 December 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dallapiccola, Anna L. (2001). "Relief carvings on the great platform". In John M. Fritz; George Michell (eds.). New Light on Hampi: Recent Research at Vijayanagara. Mumbai: MARG. ISBN 978-81-85026-53-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davison-Jenkins, Dominic J. (2001). "Hydraulic works". In John M. Fritz; George Michell (eds.). New Light on Hampi: Recent Research at Vijayanagara. Mumbai: MARG. ISBN 978-81-85026-53-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Durga Prasad, J. (1988). History of the Andhras up to 1565 A. D. (PDF). Guntur: P.G. Publisher. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2006. Retrieved 27 January 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eaton, Richard M. (2006). A social history of the Deccan, 1300–1761: eight Indian lives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-71627-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hampi travel guide (2003). New Delhi: Good Earth publication & Department of Tourism, India. ISBN 81-87780-17-7, LCCN 2003-334582.

- Fritz, John M.; Michell, George, eds. (2001). New Light on Hampi: Recent Research at Vijayanagar. Mumbai: MARG. ISBN 978-81-85026-53-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Iyer, Panchapakesa A.S. (2006) [2006]. Karnataka Sangeeta Sastra. Chennai: Zion Printers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kamath, Suryanath U. (2001) [1980]. A concise history of Karnataka: from pre-historic times to the present. Bangalore: Jupiter books. LCCN 80905179. OCLC 7796041.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karmarkar, A.P. (1947) [1947]. Cultural history of Karnataka: ancient and medieval. Dharwad: Karnataka Vidyavardhaka Sangha. OCLC 8221605.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kulke and Rothermund, Hermann and Dietmar (2004) [2004]. A History of India. Routledge (4th edition). ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mack, Alexandra (2001). "The temple district of Vitthalapura". In John M. Fritz and George Michell (ed.). New Light on Hampi: Recent Research at Vijayanagara. Mumbai: MARG. ISBN 978-81-85026-53-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. (1955) [reissued 2002]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-560686-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Philon, Helen (2001). "Plaster decoration on Sultanate-styled courtly buildings". In John M. Fritz; George Michell (eds.). New Light on Hampi: Recent Research at Vijayanagara. Mumbai: MARG. ISBN 978-81-85026-53-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pujar, Narahari S.; Shrisha Rao; H.P. Raghunandan. "Sri Vyâsa Tîrtha (1460–1539) – a short sketch". Dvaita Home Page. Retrieved 31 December 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramesh, K. V. "Introduction". South Indian Inscription, Volume 16: Telugu Inscriptions from Vijayanagar Dynasty. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shiva Prakash, H.S. (1997). "Kannada". In Ayyappapanicker (ed.). Medieval Indian Literature:An Anthology. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rice, B.L. (2001) [1897]. Mysore Gazetteer Compiled for Government-vol 1. New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0977-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sewell, Robert (1901). A Forgotten Empire Vijayanagar: A Contribution to the History of India.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verghese, Anila (2001). "Memorial stones". In John M. Fritz; George Michell (eds.). New Light on Hampi: Recent Research at Vijayanagara. Mumbai: MARG. ISBN 978-81-85026-53-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thapar, Romila (2003) [2003]. The Penguin History of Early India. New Delhi: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-302989-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Michell, George (2008). Vijayanagara: Splendour in Ruins. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing and The Alkazi Collection of Photography. ISBN 978-81-89995-03-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nagaraj, D.R. (2003). "Tensions in Kannada Literary Culture". In Sheldon Pollock (ed.). Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Asher & Talbot, Catherine & Cynthia (2006). "Creation of Pan South Indian Culture". India Before Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00539-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rice, E.P. (1982) [1921]. A History of Kanarese Literature. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0063-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stein, Burton (1989). The New Cambridge History of India: Vijayanagara. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26693-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bang, Peter Fibiger; Kolodziejczyk, Dariusz, eds. (2012). "Ideologies of state building in Vijayanagara India". Universal Empire: A Comparative Approach to Imperial Culture and Representation in Eurasian History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02267-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oldham, C. E. A. W., "Reviewed Work: Vijayanagara: Origin of the City and the Empire by N. Venkata Ramanayya", The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 1, 1936, pp. 130–131. JSTOR 25182067.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vijayanagara Empire |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vijayanagara Empire. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Vijayanagar. |