Louisiana (New Spain)

Spanish Louisiana (Spanish: la Luisiana[2]) was a governorate and administrative district of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1762 to 1801 that consisted of a vast territory in the center of North America encompassing the western basin of the Mississippi River plus New Orleans. The area had originally been claimed and controlled by France, which had named it La Louisiane in honor of King Louis XIV in 1682. Spain secretly acquired the territory from France near the end of the Seven Years' War by the terms of the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762). The actual transfer of authority was a slow process, and after Spain finally attempted to fully replace French authorities in New Orleans in 1767, French residents staged an uprising which the new Spanish colonial governor did not suppress until 1769. Spain also took possession of the trading post of St. Louis and all of Upper Louisiana in the late 1760s, though there was little Spanish presence in the wide expanses of the "Illinois Country".

Governorate of Luisiana la Luisiana | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1769[1]–1801 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

_orthographic_projection.svg.png) Spanish Louisiana in 1762 | |||||||||

| Capital | Nueva Orleans[2] | ||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish (official) Louisiana French Louisiana Creole | ||||||||

| Religion | Catholic West African Vodun Louisiana Voodoo | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1769[3] | |||||||||

| 21 March 1801 | |||||||||

| Currency | Spanish dollar | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Canada United States | ||||||||

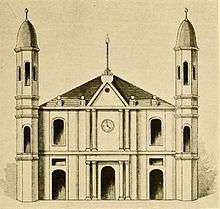

New Orleans was the main port of entry for Spanish supplies sent to American forces during the American Revolution, and Spain and the new United States disputed the borders of Louisiana and navigation rights on the Mississippi River for the duration of Spain's rule in the colony. New Orleans was devastated by large fires in 1788 and 1794 which destroyed most of the original wooden buildings in what is today the French Quarter. New construction was done in the Spanish style with stone walls and slate roofs, and new public buildings constructed during the city's Spanish period include several still standing today such as the St. Louis Cathedral, the Cabildo, and the Presbytere.[4]

Louisiana was later and briefly retroceded back to France under the terms of the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso (1800) and the Treaty of Aranjuez (1801). In 1802, King Charles IV of Spain published a royal bill on 14 October, effecting the transfer and outlining the conditions. Spain agreed to continue administering the colony until French officials arrived and formalized the transfer. After several delays, the official transfer of ownership took place at the Cabildo in New Orleans on 30 November 1803. Three weeks later on 20 December, another ceremony was held at the same location in which France transferred New Orleans and the surrounding area to the United States pursuant to the Louisiana Purchase. Upper Louisiana was officially transferred to France and then to the United States on Three Flags Day in St. Louis, which was a series of ceremonies held over two days on 9 and 10 March 1804.[5]

History

| History of Louisiana |

|---|

|

|

|

Spain was largely a benign absentee landlord administering the territory from Havana, Cuba, and contracting out governing to people from many nationalities as long as they swore allegiance to Spain. During the American Revolutionary War, the Spanish funneled their supplies to the American revolutionists through New Orleans and the vast Louisiana territory beyond.

In keeping with being absentee landlords, Spanish efforts to turn Louisiana into a Spanish colony were usually fruitless. For instance, while Spanish officially was the only language of government, the majority of the populace firmly continued to speak French. Even official business conducted at the Cabildo often lapsed into French, requiring an interpreter to be on hand.[6]

Slavery

When Alejandro O'Reilly re-established Spanish rule in 1769, he issued a decree on 7 December of that year which banned the trade of Native American slaves.[7] Although there was no movement toward abolition of the African slave trade, Spanish rule introduced a new law called coartación, which allowed slaves to buy their freedom and that of others.[8]

A group of maroons led by Jean Saint Malo resisted re-enslavement from their base in the swamps east of New Orleans between 1780 and 1784.[9]

Pointe Coupée conspiracy

On 4 May 1795, 57 slaves and 3 local white men were put on trial in Point Coupee. At the end of the trial 23 slaves were hanged, 31 slaves received a sentence of flogging and hard labor, and the three white men were deported, with two being sentenced to six years forced labor in Havana.[7]

Upper and Lower, or the Louisianas

Spanish colonial officials divided Luisiana into Upper Louisiana (Alta Luisiana) and Lower Louisiana (Baja Luisiana) at 36° 35' North, about the latitude of New Madrid, Missouri.[10] This was a higher latitude than during the French administration, for whom Lower Louisiana was the area south of about 31° North (the current northern boundary of the state of Louisiana) or the area south of where the Arkansas River joined the Mississippi River at about 33° 46' North latitude.

In 1764, French fur trading interests founded St. Louis in what was then known as the Illinois Country. The Spanish referred to St. Louis as "the city of Illinois" and governed the region from St. Louis as the "District of Illinois".[11]

Spanish communities in Louisiana

To establish Spanish colonies in Louisiana, the Spanish military leader Bernardo de Gálvez, governor of Louisiana at the time, recruited groups of Spanish-speaking Canary Islanders to emigrate to North America.[12] In 1778, several ships embarked for Louisiana with hundreds of settlers. The ships made stops in Havana and Venezuela, where half the settlers disembarked (300 Canarians remained in Venezuela). In the end, between 2,100[13] and 2,736[14] Canarians arrived in Louisiana and settled near New Orleans. They settled in Barataria and in what is today St. Bernard Parish. However, many settlers were relocated for various reasons. Barataria suffered hurricanes in 1779 and in 1780; it was abandoned and its population distributed in other areas of colonial Louisiana (although some of its settlers moved to West Florida).[15] In 1782, a splinter group of the Canarian settlers in Saint Bernard emigrated to Valenzuela.[14]

In 1779, another ship with 500 people from Málaga (in Andalusia, Spain), arrived in Spanish Louisiana. These colonists, led by Lt. Col. Francisco Bouligny, settled in New Iberia, where they intermarried with Cajun settlers.[16]

In 1782, during the American Revolutionary War and the Anglo-Spanish War (1779–83), Bernardo de Gálvez recruited men from the Canarian settlements of Louisiana and Galveston (in Spanish Texas, where Canarians had settled since 1779) to join his forces. They participated in three major military campaigns: the Baton Rouge, the Mobile, and the Pensacola, which expelled the British from the Gulf Coast. In 1790 settlers of mixed Canarian and Mexican origin from Galveston settled in Galveztown, Louisiana, to escape the annual flash floods and prolonged droughts of this area.[14]

Immigration from Saint-Domingue

Beginning in the 1790s, following the slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) that began in 1791, waves of refugees came to Louisiana. Over the next decade, thousands of migrants from the island landed there, including ethnic Europeans, free people of color, and African slaves, some of the latter brought in by the white elites. They greatly increased the French-speaking population in New Orleans and Louisiana, as well as the number of Africans, and the slaves reinforced African culture in the city.[17]

Timeline

French control

The French established settlements in French Louisiana beginning in the 17th century. The French began exploring the region from French Canada.

Spanish control

- 1762 – As negotiations began to end the Seven Years' War, Louis XV of France secretly proposed to his cousin Charles III of Spain that France give Louisiana to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau.

- 1763 – The Treaty of Paris ended the war, with a provision by which France ceded all territory east of the Mississippi (including Canada) to Britain. Spain ceded Florida and land east of the Mississippi (including Baton Rouge) to Britain.

- 1763 – George III of the United Kingdom, in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, proclaimed that all land east of the Mississippi acquired in the war – with the exception of East Florida, West Florida and Quebec – would become an Indian Reserve.

- 1763 – The Acadian (Cajun) migration began: French settlers had been ordered to leave the new Indian Reserve in Quebec. Settlers from the east side of the Mississippi also migrated to Louisiana. The new arrivals believed the territory was still French-controlled land.

- 1764 – Pierre Laclède established the Maxent, Laclède & Company trading post at St. Louis.

- 1764 – Spain's acquisition of Louisiana from France was formally announced.

- 1765 – Joseph Broussard led the first group of nearly 200 Acadians to settle on Bayou Teche below present-day St. Martinville, Louisiana.[18]

- 1768 – Antonio de Ulloa became the first Spanish governor of Louisiana.[19] He did not fly the Spanish flag and was forced to leave by a pro-French mob in the Rebellion of 1768.[20]

- 1769 – Alejandro O'Reilly suppressed the rebellion, executed its leaders, and sent some plotters to prison in Morro Castle in Havana. He was otherwise benign and pardoned other participants who swore allegiance to Spain. He established Spanish law and the cabildo (council) of New Orleans.

- 1770 – Luis de Unzaga freed the imprisoned rebels.

- 1780 & 1783 – The Battle of Saint Louis and the Battle of Arkansas Post were the only military engagements fought west of the Mississippi River during the American Revolutionary War.

- 1788 – The Great New Orleans Fire destroyed virtually all of New Orleans. Governor Esteban Rodríguez Miró was respected for his relief efforts.

- 1789 – Work on rebuilding New Orleans began, the city at that time being limited to what is now the French Quarter. The new structures had courtyards and masonry walls. The cornerstone for the new St. Louis Cathedral was laid.

- 1795 – Pinckney's Treaty settled boundary disputes with the United States and recognized its right to navigate through New Orleans.

- 1798 – Spain revoked the United States' right to travel through New Orleans.

- 1799 – The newly-rebuilt Cabildo opened.

French control

- 1800 – In the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso, Napoleon secretly acquired the territory, but Spain continued to administer it.[21]

- 1801 – The United States was permitted again to use the port of New Orleans.

- 1803 – The Sale of Louisiana to the United States was announced.

- 1803 – Spain refused Lewis and Clark permission to travel up the Missouri River, since the transfer from France to the United States had not been made official; they spent the winter in Illinois at Camp Dubois.

- 1803 – On 30 November 1803, Spanish officials formally conveyed the colonial lands and their administration to France.

- 1803 – France turned over New Orleans, the historic colonial capital, to the United States on 20 December 1803.

- 1804 – On 9 and 10 March, a ceremony, now commemorated as Three Flags Day, was conducted in St. Louis to transfer ownership of Upper Louisiana from Spain to the French First Republic, and then from France to the United States.

See also

References

- Chambers, Henry E. (May 1898). West Florida and its relation to the historical cartography of the United States. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 48.

- José Presas y Marull (1828). Juicio imparcial sobre las principales causas de la revolución de la América Española y acerca de las poderosas razones que tiene la metrópoli para reconocer su absoluta independencia. (original document) [Fair judgment about the main causes of the revolution of Spanish America and about the powerful reasons that the metropolis has for recognizing its absolute independence]. Burdeaux: Imprenta de D. Pedro Beaume. pp. 22, 23.

- Chambers, Henry E. (May 1898). West Florida and its relation to the historical cartography of the United States. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 48.

- "French Quarter Fire and Flood". FrenchQuarter.com. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "March 9–10: Three Flags Day". Florida Center for Instructional Technology. FCIT. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Din, Gilbert C.; Harkins, John E. (1996), New Orleans Cabildo: Colonial Louisiana's First City Government, 1769—1803, Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, ISBN 978-0-8071-2042-2, retrieved 9 July 2020

- Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (1995). Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0807119990.

- Berquist, Emily (2010). "Early Anti-Slavery Sentiment in the Spanish Atlantic World, 1765–1817". Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies. 31 (2): 181–205. doi:10.1080/01440391003711073.

- Kaplan-Levenson, Lanie (10 December 2015). "More Than A Runaway: Maroons In Louisiana". WWNO-FM. New Orleans, Louisiana. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- Reasonover, John R.; Michelle M. Haas (2005). Reasonover's Land Measures. Copano Bay Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-9767799-0-2.

- Ekberg, Carl (2000). French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times. Urbana and Chicago, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9780252069246.

- Santana Pérez, Juan Manuel; Sánchez Suárez, José Antonio (1992). Emigración por Reclutamientos Canarios en Luisiana [Emigration by Canarian recruitments in Louisiana] (in Spanish). Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain: Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria Servicio de Publicaciones. p. 133. ISBN 978-84-88412-62-1.

- Armistead, Samuel G. (2007), La Tradición Hispano–Canaria en Luisiana: La Literatura Tradicional de los Isleños [The Hispanic–Canarian Tradition in Louisiana: Traditional Literature of the Isleños] (in Spanish), Madrid: Celesa, pp. 51–61, ISBN 978-84-96887-08-4

- "St. Bernard Isleños: Louisiana's Spanish Treasure". The Los Isleños Heritage & Cultural Society Museum. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Hernández González, Manuel (2007). La emigración canaria a América [Canarian Emigration to the Americas] (in Spanish). pp. 15, 43–44 (Canarian emigration of Florida and Texas); p. 51 (Canarian emigration to Louisiana). First Edition

- Din, Gilbert C. (Spring 1976). "Lieutenant Colonel Francisco Bouligny and the Malagueño Settlement at New Iberia, 1779". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 17 (2): 187–202. JSTOR 4231587.

- "The Slave Rebellion of 1791". Library of Congress Country Studies.

- Bradshaw, Jim (27 January 1998). "Broussard named for early settler Valsin Broussard". Lafayette Daily Advertiser. Archived from the original on 21 May 2009.

- Hernández Sánchez Barba, Mario. "Antonio de Ulloa, primer gobernador español en Nueva Orleans". Repositorio Español de Ciencia y Tecnología (in Spanish): 32-34. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Acosta Rodríguez, Antonio (1978). "Porblemas económicos y rebelión popular en Luisiana en 1768" (in Spanish). Universidad de Sevilla: 131-146. Retrieved 27 June 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Louisiana Purchase". Library of Congress: 54-68. Retrieved 27 June 2020.