Marrakesh

Marrakesh (/məˈrækɛʃ/ or /ˌmærəˈkɛʃ/;[4] Arabic: مراكش Marākiš; Berber languages: ⴰⵎⵓⵔⴰⴽⵓⵛ, romanized: Amurakuc, French: Marrakech) [5] is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco.[3] It is the capital of the mid-southwestern region of Marrakesh-Safi. It is west of the foothills of the Atlas Mountains. Marrakesh is 580 km (360 mi) southwest of Tangier, 327 km (203 mi) southwest of the Moroccan capital of Rabat, 239 km (149 mi) south of Casablanca, and 246 km (153 mi) northeast of Agadir.

Marrakesh مراكش ⴰⵎⵓⵔⴰⴽⵓⵛ Marrakech | |

|---|---|

Prefecture-level city | |

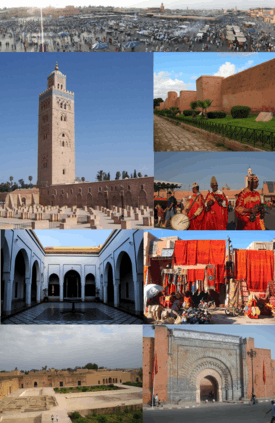

Clockwise, from top: Jemaa el-Fnaa, Saadian wall, Musicians on Jemaa el-Fnaa, Local handicraft, Bab Agnaou, El-Badi Palace, Bahia Palace, Koutoubia Mosque. | |

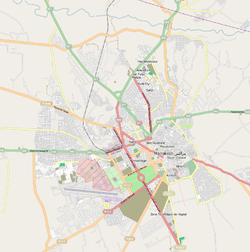

Map of Marrakesh | |

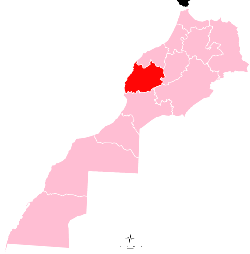

Marrakesh Location of Marrakesh within Morocco  Marrakesh Marrakesh (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 31°37′48″N 8°0′32″W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Marrakesh-Safi |

| Prefecture | Marrakesh |

| Established | 1062 |

| Founded by | Abu Bakr ibn Umar |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mohamed Larbi Belcaid[1] |

| Elevation | 466 m (1,529 ft) |

| Population (2014)[2] | |

| • Total | 928,850 |

| • Rank | 4th in Morocco[lower-alpha 1] |

| Demonym(s) | Marrakshi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| |

The region has been inhabited by Berber farmers since Neolithic times. The city was founded in 1062, by Abu Bakr ibn Umar, a chieftain and cousin of the Almoravid king, Yusuf ibn Tashfin, as the imperial capital of the Almoravid Empire. The city was one of Morocco's four imperial cities. In the 12th century, the Almoravids built many madrasas (Quranic schools) and mosques in Marrakesh that bear Andalusian influences. The red walls of the city, built by Ali ibn Yusuf in 1122–1123, and various buildings constructed in red sandstone during this period, have given the city the nickname of the "Red City" (المدينة الحمراء) or "Ochre City" (ville ocre). Marrakesh grew rapidly and established itself as a cultural, religious, and trading center for the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa. Jemaa el-Fnaa is the busiest square in Africa.

After a period of decline, the city was surpassed by Fez, but in the early 16th century, Marrakesh again became the capital of the kingdom. The city regained its preeminence under wealthy Saadian sultans Abu Abdallah al-Qaim and Ahmad al-Mansur, who embellished the city with sumptuous palaces such as the El Badi Palace (1578) and restored many ruined monuments. Beginning in the 17th century, the city became popular among Sufi pilgrims for its seven patron saints who are entombed here. In 1912 the French Protectorate in Morocco was established and T'hami El Glaoui became Pasha of Marrakesh and held this position nearly throughout the protectorate until the role was dissolved upon the independence of Morocco and the reestablishment of the monarchy in 1956. In 2009, Marrakesh mayor Fatima Zahra Mansouri became the second woman to be elected mayor in Morocco.

Marrakesh comprises an old fortified city packed with vendors and their stalls. This medina quarter is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[6] Today it is one of the busiest cities in Africa and serves as a major economic center and tourist destination. Tourism is strongly advocated by the reigning Moroccan monarch, Mohammed VI, with the goal of doubling the number of tourists visiting Morocco to 20 million by 2020. Despite the economic recession, real estate and hotel development in Marrakesh have grown dramatically in the 21st century. Marrakesh is particularly popular with the French, and numerous French celebrities own property in the city. Marrakesh has the largest traditional market (souk) in Morocco, with some 18 souks selling wares ranging from traditional Berber carpets to modern consumer electronics. Crafts employ a significant percentage of the population, who primarily sell their products to tourists.

Marrakesh is served by Ménara International Airport and by Marrakesh railway station which connects the city to Casablanca and northern Morocco. Marrakesh has several universities and schools, including Cadi Ayyad University. A number of Moroccan football clubs are here, including Najm de Marrakech, KAC Marrakech, Mouloudia de Marrakech and Chez Ali Club de Marrakech. The Marrakesh Street Circuit hosts the World Touring Car Championship, Auto GP and FIA Formula Two Championship races.

Etymology

The exact meaning of the name is debated.[7] One possible origin of the name Marrakesh is from the Berber (Amazigh) words amur (n) akush (ⴰⵎⵓⵔ ⵏ ⴰⴽⵓⵛ), which means "Land of God".[5] According to historian Susan Searight, however, the town's name was first documented in an 11th-century manuscript in the Qarawiyyin library in Fez, where its meaning was given as "country of the sons of Kush".[8] The word mur [9] is used now in Berber mostly in the feminine form tamurt. The same word "mur" appears in Mauretania, the North African kingdom from antiquity, although the link remains controversial as this name possibly originates from μαύρος mavros, the ancient Greek word for black.[7] The common English spelling is "Marrakesh",[10][11] although "Marrakech" (the French spelling) is also widely used.[5] The name is spelt Mṛṛakc in the Berber Latin alphabet, Marraquexe in Portuguese, Marraquech in Spanish,[10][11] and "Mer-raksh" in Moroccan Arabic.[9]

From medieval times until around the beginning of the 20th century, the entire country of Morocco was known as the "Kingdom of Marrakesh", as the kingdom's historic capital city was often Marrakesh.[12][13] The name for Morocco is still "Marrakesh" (مراكش) to this day in Persian and Urdu as well as many other South Asian languages. Various European names for Morocco (Marruecos, Marrocos, Maroc, Marokko, etc.) are directly derived from the Berber word Murakush. Conversely, the city itself was in earlier times simply called Marocco City (or similar) by travelers from abroad. The name of the city and the country diverged after the Treaty of Fez divided Morocco into a French protectorate in Morocco and Spanish protectorate in Morocco, but the old interchangeable usage lasted widely until about the interregnum of Mohammed Ben Aarafa (1953–1955).[14] The latter episode set in motion the country's return to independence, when Morocco officially became المملكة المغربية (al-Mamlaka al-Maġribiyya, "The Maghreb Kingdom"), its name no longer referring to the city of Marrakesh. Marrakesh is known by a variety of nicknames, including the "Red City", the "Ochre City" and "the Daughter of the Desert", and has been the focus of poetic analogies such as one comparing the city to "a drum that beats an African identity into the complex soul of Morocco."[15]

History

The Marrakesh area was inhabited by Berber farmers from Neolithic times, and numerous stone implements have been unearthed in the area.[8] Marrakesh was founded in 1062 (454 in the Hijri calendar) by Abu Bakr ibn Umar, chieftain and second cousin of the Almoravid king Yusuf ibn Tashfin (c. 1061–1106).[16][17][18] Under the berber dynasty of the Almoravids, pious and learned warriors from the desert, numerous mosques and madrasas (Quranic schools) were built, developing the community into a trading centre for the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa.[19] Marrakesh grew rapidly and established itself as a cultural and religious centre, supplanting Aghmat, which had long been the capital of Haouz. Andalusian craftsmen from Cordoba and Seville built and decorated numerous palaces in the city, developing the Umayyad style characterised by carved domes and cusped arches.[8][20] This Andalusian influence merged with designs from the Sahara and West Africa, creating a unique style of architecture which was fully adapted to the Marrakesh environment. Yusuf ibn Tashfin completed the city's first mosque (the Ben Youssef mosque, named after his son), built houses, minted coins, and brought gold and silver to the city in caravans.[8] The city became the capital of the Almoravid Emirate,[21] stretching from the shores of Senegal to the centre of Spain and from the Atlantic coast to Algiers.

Marrakesh is one of the great citadels of the Muslim world.[15] The city was fortified by Tashfin's son, Ali ibn Yusuf, who in 1122–1123 built the ramparts which remain to this day, completed further mosques and palaces, and developed an underground water system in the city known as the rhettara to irrigate his new garden.[8] In 1125, the preacher Ibn Tumert settled in Tin Mal in the mountains to the south of Marrakesh. He preached against the Almoravids and influenced a revolt which succeeded in bringing about the fall of nearby Aghmat, but stopped short of bringing down Marrakesh following an unsuccessful siege in 1130.[8] The Almohads, Masmouda tribesmen from the High Atlas mountains who practiced orthodox Islam, took the city in 1147 under leader Abd al-Mu'min.[8] After a long siege and the killing of some 7,000 people, the last of the Almoravids were exterminated apart from those who sought exile in the Balearic Islands. As a result, almost all the city's monuments were destroyed.[8] The Almohads constructed a range of palaces and religious buildings, including the famous Koutoubia Mosque (1184–1199), and built upon the ruins of an Almoravid palace.[8] It was a twin of the Giralda in Seville and the unfinished Hassan Tower in Rabat, all built by the same designer.[22] The Kasbah housed the residence of the caliph, a title borne by the Almohad rulers from the reign of Abd al-Mu'min, rivaling the far eastern Abbasid Caliphate. The Kasbah was built by the caliph Yaqub al-Mansur. The irrigation system was perfected to provide water for new palm groves and parks, including the Menara Garden.[8] As a result of its cultural reputation, Marrakesh attracted many writers and artists, especially from Andalusia, including the famous philosopher Averroes of Cordoba.

The death of Yusuf II in 1224 began a period of instability. Marrakesh became the stronghold of the Almohad tribal sheikhs and the ahl ad-dar (descendants of Ibn Tumart), who sought to claw power back from the ruling Almohad family. Marrakesh was taken, lost and retaken by force multiple times by a stream of caliphs and pretenders, such as during the brutal seizure of Marrakesh by the Sevillan caliph Abd al-Wahid II al-Ma'mun in 1226, which was followed by a massacre of the Almohad tribal sheikhs and their families and a public denunciation of Ibn Tumart's doctrines by the caliph from the pulpit of the Kasbah Mosque.[23] After al-Ma'mun's death in 1232, his widow attempted to forcibly install her son, acquiring the support of the Almohad army chiefs and Spanish mercenaries with the promise to hand Marrakesh over to them for the sack. Hearing of the terms, the people of Marrakesh sought to make an agreement with the military captains and saved the city from destruction with a sizable payoff of 500,000 dinars.[23] In 1269, Marrakesh was conquered by nomadic Zenata tribes who overran the last of the Almohads.[24] The city then fell into a state of decline, which soon led to the loss of its status as capital to rival city Fez.

In the early 16th century, Marrakesh again became the capital of the kingdom, after a period when it was the seat of the Hintata emirs. It quickly reestablished its status, especially during the reigns of the Saadian sultans Abu Abdallah al-Qaim and Ahmad al-Mansur. Thanks to the wealth amassed by the Sultans, Marrakesh was embellished with sumptuous palaces while its ruined monuments were restored. El Badi Palace, built by Ahmad al-Mansur in 1578, was a replica of the Alhambra Palace, made with costly and rare materials including marble from Italy, gold dust from Sudan, porphyry from India and jade from China. The palace was intended primarily for hosting lavish receptions for ambassadors from Spain, England, and the Ottoman Empire, showcasing Saadian Morocco as a nation whose power and influence reached as far as the borders of Niger and Mali.[25] Under the Saadian dynasty, Marrakesh regained its former position as a point of contact for caravan routes from the Maghreb, the Mediterranean and sub-Saharan Africa.

For centuries Marrakesh has been known as the location of the tombs of Morocco's seven patron saints (sebaatou rizjel). When sufism was at the height of its popularity during the late 17th-century reign of Moulay Ismail, the festival of these saints was founded by Abu Ali al-Hassan al-Yusi at the request of the sultan.[26] The tombs of several renowned figures were moved to Marrakesh to attract pilgrims, and the pilgrimage associated with the seven saints is now a firmly established institution. Pilgrims visit the tombs of the saints in a specific order, as follows: Sidi Yusuf Ali Sanhaji (1196–97), a leper; Qadi Iyyad or qadi of Ceuta (1083–1149), a theologian and author of Ash-Shifa (treatises on the virtues of Muhammad); Sidi Bel Abbas (1130–1204), known as the patron saint of the city and most revered in the region; Sidi Muhammad al-Jazuli (1465), a well known Sufi who founded the Jazuli brotherhood; Abdelaziz al-Tebaa (1508), a student of al-Jazuli; Abdallah al-Ghazwani (1528), known as Moulay al-Ksour; and Sidi Abu al-Qasim Al-Suhayli, (1185), also known as Imam al-Suhayli.[27][28] Until 1867, European Christians were not authorized to enter the city unless they acquired special permission from the sultan; east European Jews were permitted.[13]

During the early 20th century, Marrakesh underwent several years of unrest. After the premature death in 1900 of the grand vizier Ba Ahmed, who had been designated regent until the designated sultan Abd al-Aziz became of age, the country was plagued by anarchy, tribal revolts, the plotting of feudal lords, and European intrigues. In 1907, Marrakesh caliph Moulay Abd al-Hafid was proclaimed sultan by the powerful tribes of the High Atlas and by Ulama scholars who denied the legitimacy of his brother, Abd al-Aziz.[29] It was also in 1907 that Dr. Mauchamp, a French doctor, was murdered in Marrakesh, suspected of spying for his country.[30] France used the event as a pretext for sending its troops from the eastern Moroccan town of Oujda to the major metropolitan center of Casablanca in the west. The French colonial army encountered strong resistance from Ahmed al-Hiba, a son of Sheikh Ma al-'Aynayn, who arrived from the Sahara accompanied by his nomadic Reguibat tribal warriors. On 30 March 1912, the French Protectorate in Morocco was established.[31] After the Battle of Sidi Bou Othman, which saw the victory of the French Mangin column over the al-Hiba forces in September 1912, the French seized Marrakesh. The conquest was facilitated by the rallying of the Imzwarn tribes and their leaders from the powerful Glaoui family, leading to a massacre of Marrakesh citizens in the resulting turmoil.[32]

T'hami El Glaoui, known as "Lord of the Atlas", became Pasha of Marrakesh, a post he held virtually throughout the 44-year duration of the Protectorate (1912–1956).[33] Glaoui dominated the city and became famous for his collaboration with the general residence authorities, culminating in a plot to dethrone Mohammed Ben Youssef (Mohammed V) and replace him with the Sultan's cousin, Ben Arafa.[33] Glaoui, already known for his amorous adventures and lavish lifestyle, became a symbol of Morocco's colonial order. He could not, however, subdue the rise of nationalist sentiment, nor the hostility of a growing proportion of the inhabitants. Nor could he resist pressure from France, who agreed to terminate its Moroccan Protectorate in 1956 due to the launch of the Algerian War (1954–1962) immediately following the end of the war in Indochina (1946–1954), in which Moroccans had been conscripted to fight in Vietnam on behalf of the French Army. After two successive exiles to Corsica and Madagascar, Mohammed Ben Youssef was allowed to return to Morocco in November 1955, bringing an end to the despotic rule of Glaoui over Marrakesh and the surrounding region. A protocol giving independence to Morocco was then signed on 2 March 1956 between French Foreign Minister Christian Pineau and M’Barek Ben Bakkai.[34]

.jpg)

Since the independence of Morocco, Marrakesh has thrived as a tourist destination. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the city became a trendy "hippie mecca". It attracted numerous western rock stars and musicians, artists, film directors and actors, models, and fashion divas,[35] leading tourism revenues to double in Morocco between 1965 and 1970.[36] Yves Saint Laurent, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Jean-Paul Getty all spent significant time in the city; Laurent bought a property here and renovated the Majorelle Gardens.[37][38] Expatriates, especially those from France, have invested heavily in Marrakesh since the 1960s and developed many of the riads and palaces.[37] Old buildings were renovated in the Old Medina, new residences and commuter villages were built in the suburbs, and new hotels began to spring up.

United Nations agencies became active in Marrakesh beginning in the 1970s, and the city's international political presence has subsequently grown. In 1985, UNESCO declared the old town area of Marrakesh a UNESCO World Heritage Site, raising international awareness of the cultural heritage of the city.[39] In the 1980s, Patrick Guerand-Hermes purchased the 30 acres (12 ha) Ain el Quassimou, built by the family of Leo Tolstoy. [38] On 15 April 1994, the Marrakesh Agreement was signed here to establish the World Trade Organisation,[40] and in March 1997 Marrakesh served as the site of the World Water Council's first World Water Forum, which was attended by over 500 international participants.[41]

From November 7 to 18, 2016, the city of Marrakesh was host to the meeting of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), known as the 22nd Session of the Conference of the Parties, or COP 22. Also known as 2016 United Nations Climate Change Conference it also served as the first meeting of the governing body of the Paris Agreement, known by the acronym CMA1. The UNFCCC secretariat (UN Climate Change) was established in 1992 when countries adopted the UNFCCC. In recent years, the secretariat also supports the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action, agreed by governments to signal that successful climate action requires strong support from a wide range of actors, including regions, cities, business, investors and all parts of civil society.[42] Commencing six months ahead of the start of the UN Climate Change Conference in Marrakesh, construction work at the Bab Ighli site was launched. The site was composed of two zones. The “Blue Zone”, placed under the authority of the United Nations, and spanning 154,000 m2 and consisting notably of two plenary rooms, 30 conference and meeting rooms for negotiators and 10 meeting rooms reserved for observers. The second zone, the "Green Zone", was reserved for non-state actors, NGOs, private companies, state institutions and organizations, and local authorities within two areas (“civil society” and “innovations”) each measuring 12,000 m2. The area will also include spaces dedicated to exhibitions and restaurants. The total surface of the Bab Ighli site will be 223,647 m2 (more than 80,000 m2 covered by a roof).[43]

In the 21st century, property and real estate development in the city has boomed, with a dramatic increase in new hotels and shopping centres, fuelled by the policies of Mohammed VI of Morocco, who aims to increase the number of tourists annually visiting Morocco to 20 million by 2020. In 2010, a major gas explosion occurred in the city. On 28 April 2011, a bomb attack took place in the Jemaa el-Fnaa square, killing 15 people, mainly foreigners. The blast destroyed the nearby Argana Cafe.[44] Police sources arrested three suspects and claimed the chief suspect was loyal to Al-Qaeda, although Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb denied involvement.[45] In November 2016 the city hosted the 2016 United Nations Climate Change Conference.

Geography

By road, Marrakesh is 580 kilometres (360 mi) southwest of Tangier, 327 kilometres (203 mi) southwest of the Moroccan capital of Rabat, 239 kilometres (149 mi) southwest of Casablanca, 196 kilometres (122 mi) southwest of Beni Mellal, 177 kilometres (110 mi) east of Essaouira, and 246 kilometres (153 mi) northeast of Agadir.[46] The city has expanded north from the old centre with suburbs such as Daoudiat, Diour El Massakine, Sidi Abbad, Sakar and Amerchich, to the southeast with Sidi Youssef Ben Ali, to the west with Massira and Targa, and southwest to M'hamid beyond the airport.[46] On the P2017 road leading south out of the city are large villages such as Douar Lahna, Touggana, Lagouassem, and Lahebichate, leading eventually through desert to the town of Tahnaout at the edge of the High Atlas, the highest mountainous barrier in North Africa.[46] The average elevation of the snow-covered High Atlas lies above 3,000 metres (9,800 ft). It is mainly composed of Jurassic limestone. The mountain range runs along the Atlantic coast, then rises to the east of Agadir and extends northeast into Algeria before disappearing into Tunisia.[47]

The Ourika River valley is about 30 kilometres (19 mi) south of Marrakesh.[48] The "silvery valley of the Ourika river curving north towards Marrakesh", and the "red heights of Jebel Yagour still capped with snow" to the south are sights in this area.[49] David Prescott Barrows, who describes Marrakesh as Morocco's "strangest city", describes the landscape in the following terms: "The city lies some fifteen or twenty miles [25–30 km] from the foot of the Atlas mountains, which here rise to their grandest proportions. The spectacle of the mountains is superb. Through the clear desert air the eye can follow the rugged contours of the range for great distances to the north and eastward. The winter snows mantle them with white, and the turquoise sky gives a setting for their grey rocks and gleaming caps that is of unrivaled beauty."[32]

With 130,000 hectares of greenery and over 180,000 palm trees in its Palmeraie, Marrakesh is an oasis of rich plant variety. Throughout the seasons, fragrant orange, fig, pomegranate and olive trees display their color and fruits in Agdal Garden, Menara Garden and other gardens in the city.[50] The city's gardens feature numerous native plants alongside other species that have been imported over the course of the centuries, including giant bamboos, yuccas, papyrus, palm trees, banana trees, cypress, philodendrons, rose bushes, bougainvilleas, pines and various kinds of cactus plants.

Climate

A hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh) predominates at Marrakesh. Average temperatures range from 12 °C (54 °F) in the winter to 26–30 °C (79–86 °F) in the summer.[51] The relatively wet winter and dry summer precipitation pattern of Marrakesh mirrors precipitation patterns found in Mediterranean climates. However, the city receives less rain than is typically found in a Mediterranean climate, resulting in a semi-arid climate classification. Between 1961 and 1990 the city averaged 281.3 millimetres (11.1 in) of precipitation annually.[51] Barrows says of the climate, "The region of Marrakesh is frequently described as desert in character, but, to one familiar with the southwestern parts of the United States, the locality does not suggest the desert, but rather an area of seasonal rainfall, where moisture moves underground rather than by surface streams, and where low brush takes the place of the forests of more heavily watered regions. The location of Marrakesh on the north side of the Atlas, rather than the south, prevents it from being described as a desert city, but it remains the northern focus of the Saharan lines of communication, and its history, its types of dwellers, and its commerce and arts, are all related to the great south Atlas spaces that reach further into the Sahara desert."[52]

| Climate data for Marrakesh, Morocco (Menara International Airport) 1961–1990, extremes 1900–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.1 (86.2) |

34.3 (93.7) |

37.0 (98.6) |

39.6 (103.3) |

44.4 (111.9) |

46.9 (116.4) |

49.6 (121.3) |

48.6 (119.5) |

44.8 (112.6) |

38.7 (101.7) |

35.2 (95.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

49.6 (121.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

31.3 (88.3) |

36.8 (98.2) |

36.5 (97.7) |

32.5 (90.5) |

27.5 (81.5) |

22.2 (72.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.3 (27.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.4 (32.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 32.2 (1.27) |

37.9 (1.49) |

37.8 (1.49) |

38.8 (1.53) |

23.7 (0.93) |

4.5 (0.18) |

1.2 (0.05) |

3.4 (0.13) |

5.9 (0.23) |

23.9 (0.94) |

40.6 (1.60) |

31.4 (1.24) |

281.3 (11.07) |

| Average precipitation days | 7.6 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 4.8 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 58.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65 | 66 | 61 | 60 | 58 | 55 | 47 | 47 | 52 | 59 | 62 | 65 | 58 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 220.6 | 209.4 | 247.5 | 254.5 | 287.2 | 314.5 | 335.2 | 316.2 | 263.6 | 245.3 | 214.1 | 220.6 | 3,128.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.1 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 9.3 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 7.9 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 8.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 71 | 68 | 67 | 65 | 66 | 75 | 77 | 78 | 73 | 72 | 65 | 71 | 71 |

| Source 1: NOAA,[51] Weather Atlas (percent sunshine) [53] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (record highs for February, April, May, September and November, and humidity),[54] Meteo Climat (record highs and record lows for June, July and August only)[55] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Marrakesh | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 12.1 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7.3 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [53] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

According to the 2014 census, the population of Marrakesh was 928,850 against 843,575 in 2004. The number of households in 2014 was 217,245 against 173,603 in 2004.[56][57]

Economy

.jpg)

Marrakesh is a vital component to the economy and culture of Morocco.[58] Improvements to the highways from Marrakesh to Casablanca, Agadir and the local airport have led to a dramatic increase in tourism in the city, which now attracts over two million tourists annually. Because of the importance of tourism to Morocco's economy, King Mohammed VI has vowed to attract 20 million tourists a year to Morocco by 2020, doubling the number of tourists from 2012.[59] The city is popular with the French, and many French celebrities have bought property in the city, including fashion moguls Yves St Laurent and Jean-Paul Gaultier.[60] In the 1990s very few foreigners lived in the city, but real estate developments have dramatically increased in the last 15 years; by 2005 over 3,000 foreigners had purchased properties in the city, lured by its culture and the relatively cheap house prices.[60] It has been cited in French weekly magazine Le Point as the second St Tropez: "No longer simply a destination for a scattering of adventurous elites, bohemians or backpackers seeking Arabian Nights fantasies, Marrakech is becoming a desirable stopover for the European jet set."[60] However, despite the tourism boom, the majority of the city's inhabitants are still poor, and as of 2010, some 20,000 households still have no access to water or electricity.[61] Many enterprises in the city are facing colossal debt problems.[61]

Despite the global economic crisis that began in 2007, investments in real estate progressed substantially in 2011 both in the area of tourist accommodation and social housing. The main developments have been in facilities for tourists including hotels and leisure centres such as golf courses and health spas, with investments of 10.9 billion dirham (US$1.28 billion) in 2011.[62][63] The hotel infrastructure in recent years has experienced rapid growth. In 2012, alone, 19 new hotels were scheduled to open, a development boom often compared to Dubai.[59] Royal Ranches Marrakech, one of Gulf Finance House's flagship projects in Morocco, is a 380 hectares (940 acres) resort under development in the suburbs and one of the world's first five star Equestrian Resorts.[64] The resort is expected to make a significant contribution to the local and national economy, creating many jobs and attracting thousands of visitors annually; as of April 2012 it was about 45% complete.[65] The Avenue Mohammed VI, formerly Avenue de France, is a major city thoroughfare. It has seen rapid development of residential complexes and many luxury hotels. Avenue Mohammed VI contains what is claimed to be Africa's largest nightclub:[66] Pacha Marrakech, a trendy club that plays house and electro house music.[67] It also has two large cinema complexes, Le Colisée à Gueliz and Cinéma Rif, and a new shopping precinct, Al Mazar.

.jpg)

Trade and crafts are extremely important to the local tourism-fueled economy. There are 18 souks in Marrakesh, employing over 40,000 people in pottery, copperware, leather and other crafts. The souks contain a massive range of items from plastic sandals to Palestinian-style scarves imported from India or China. Local boutiques are adept at making western-style clothes using Moroccan materials.[60] The Birmingham Post comments: "The souk offers an incredible shopping experience with a myriad of narrow winding streets that lead through a series of smaller markets clustered by trade. Through the squawking chaos of the poultry market, the gory fascination of the open-air butchers' shops and the uncountable number of small and specialist traders, just wandering around the streets can pass an entire day."[58] Marrakesh has several supermarkets including Marjane Acima, Asswak Salam and Carrefour, and three major shopping centres, Al Mazar Mall, Plaza Marrakech and Marjane Square; a branch of Carrefour opened in Al Mazar Mall in 2010.[68][69] Industrial production in the city is centred in the neighbourhood of Sidi Ghanem Al Massar, containing large factories, workshops, storage depots and showrooms. Ciments Morocco, a subsidiary of a major Italian cement firm, has a factory in Marrakech.[70] The AeroExpo Marrakech International Exhibition of aeronautical industries and services is held here, as is the Riad Art Expo.

Marrakesh is one of North Africa's largest centers of wildlife trade, despite the illegality of most of this trade.[71] Much of this trade can be found in the medina and adjacent squares. Tortoises are particularly popular for sale as pets, but Barbary macaques and snakes can also be seen.[72][73] The majority of these animals suffer from poor welfare conditions in these stalls.[74]

Politics

Marrakesh, the regional capital, constitutes a prefecture-level administrative unit of Morocco, Marrakech Prefecture, forming part of the region of Marrakech-Safi. Marrakesh is a major centre for law and jurisdiction in Morocco and most of the major courts of the region are here. These include the regional Court of Appeal, the Commercial Court, the Administrative Court, the Court of First Instance, the Court of Appeal of Commerce, and the Administrative Court of Appeal.[75] Numerous organizations of the region are based here, including the regional government administrative offices, the Regional Council of Tourism office, and regional public maintenance organisations such as the Governed Autonomous Water Supply and Electricity and Maroc Telecom.[76]

Testament to Marrakesh's development as a modern city, on 12 June 2009, Fatima-Zahra Mansouri, a then 33-year-old lawyer and daughter of a former assistant to the local authority chief in Marrakesh, was elected the first female mayor of the city, defeating outgoing Mayor Omar Jazouli by 54 votes to 35 in a municipal council vote.[77][78] Mansouri became the second woman in the history of Morocco to obtain a mayoral position, after Asma Chaabi, mayor of Essaouira.[77] The Secretary General of her Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM), Mohamed Cheikh Biadillah, stated that "her election reflects the image of a modern Morocco."[77] Her appointment was shrouded in controversy and resulted in her temporarily losing her seat the following month after a court ruled that the election had been fixed. The court found that "some ballots were distributed before the legal date and some vote records were destroyed."[79] Her party called for a 48-hour strike to "protest the plot against the democratic process."[79] On 7 July 2011, Mansouri presented her resignation from the city council of Marrakesh, but reconsidered her decision the next day.[80]

Since the legislative elections in November 2011, the ruling political party in Marrakesh has, for the first time, been the Justice and Development Party or PDJ which also rules at the national level. The party, which advocates Islamism and Islamic democracy, won five seats; the National Rally of Independents (RNI) took one seat, while the PAM won three.[81] In the partial legislative elections for the Guéliz Ennakhil constituency in October 2012, the PDJ under the leadership of Ahmed El Moutassadik was again declared the winner with 10,452 votes. The PAM, largely consisting of friends of King Mohammed VI, came in second place with 9,794 votes.[82]

Landmarks

Jemaa el-Fnaa

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Jemaa el-Fnaa place | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv, v |

| Reference | 331 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th session) |

| Area | 1,107 ha |

The Jemaa el-Fnaa is one of the best-known squares in Africa and is the centre of city activity and trade. It has been described as a "world-famous square", "a metaphorical urban icon, a bridge between the past and the present, the place where (spectacularized) Moroccan tradition encounters modernity."[83] It has been part of the UNESCO World Heritage site since 1985.[84] The name roughly means "the assembly of trespassers" or malefactors.[85] Jemaa el-Fnaa was renovated along with much of the Marrakech city, whose walls were extended by Abu Yaqub Yusuf and particularly by Yaqub al-Mansur in 1147–1158. The surrounding mosque, palace, hospital, parade ground and gardens around the edges of the marketplace were also overhauled, and the Kasbah was fortified. Subsequently, with the fluctuating fortunes of the city, Jemaa el-Fnaa saw periods of decline and renewal.[86] Historically this square was used for public decapitations by rulers who sought to maintain their power by frightening the public. The square attracted dwellers from the surrounding desert and mountains to trade here, and stalls were raised in the square from early in its history. The square attracted tradesmen, snake charmers ("wild, dark, frenzied men with long disheveled hair falling over their naked shoulders"), dancing boys of the Chleuh Atlas tribe, and musicians playing pipes, tambourines and African drums.[85] Richard Hamilton said that Jemaa el-Fnaa once "reeked of Berber particularism, of backward-looking, ill-educated countrymen, rather than the reformist, pan-Arab internationalism and command economy that were the imagined future."[87] Today the square attracts people from a diversity of social and ethnic backgrounds and tourists from all around the world. Snake charmers, acrobats, magicians, mystics, musicians, monkey trainers, herb sellers, story-tellers, dentists, pickpockets, and entertainers in medieval garb still populate the square.[84][88]

Souks

Marrakesh has the largest traditional market in Morocco and the image of the city is closely associated with its souks. Paul Sullivan cites the souks as the principal shopping attraction in the city: "A honeycomb of intricately connected alleyways, this fundamental section of the old city is a micro-medina in itself, comprising a dizzying number of stalls and shops that range from itsy kiosks no bigger than an elf's wardrobe to scruffy store-fronts that morph into glittering Aladdin's Caves once you're inside."[89] Historically the souks of Marrakesh were divided into retail areas for particular goods such as leather, carpets, metalwork and pottery. These divisions still roughly exist but with significant overlap. Many of the souks sell items like carpets and rugs, traditional Muslim attire, leather bags, and lanterns.[89] Haggling is still a very important part of trade in the souks.[90]

One of the largest souks is Souk Semmarine, which sells everything from brightly coloured bejewelled sandals and slippers and leather pouffes to jewellery and kaftans.[91] Souk Ableuh contains stalls which specialize in lemons, chilis, capers, pickles, green, red, and black olives, and mint, a common ingredient of Moroccan cuisine and tea. Similarly, Souk Kchacha specializes in dried fruit and nuts, including dates, figs, walnuts, cashews and apricots.[92] Rahba Qedima contains stalls selling hand-woven baskets, natural perfumes, knitted hats, scarves, tee shirts, Ramadan tea, ginseng, and alligator and iguana skins. Criee Berbiere, to the northeast of this market, is noted for its dark Berber carpets and rugs.[91] Souk Siyyaghin is known for its jewellery, and Souk Smata nearby is noted for its extensive collection of babouches and belts. Souk Cherratine specializes in leatherware, and Souk Belaarif sells modern consumer goods.[90] Souk Haddadine specializes in ironware and lanterns.[93]

Ensemble Artisanal is a government-run complex of small arts and crafts which offers a range of leather goods, textiles and carpets. Young apprentices are taught a range of crafts in the workshop at the back of this complex.[94]

City walls and gates

The ramparts of Marrakesh, which stretch for some 19 kilometres (12 mi) around the medina of the city, were built by the Almoravids in the 12th century as protective fortifications. The walls are made of a distinct orange-red clay and chalk, giving the city its nickname as the "red city"; they stand up to 19 feet (5.8 m) high and have 20 gates and 200 towers along them.[95] Bab Agnaou was built in the 12th century during the Almohad dynasty. The Berber name Agnaou, like Gnaoua, refers to people of Sub-Saharan African origin (cf. Akal-n-iguinawen – land of the black). The gate was called Bab al Kohl (the word kohl also meaning "black") or Bab al Qsar (palace gate) in some historical sources. The corner-pieces are embellished with floral decorations. This ornamentation is framed by three panels marked with an inscription from the Quran in Maghrebi script using foliated Kufic letters, which were also used in Al-Andalus. Bab Agnaou was renovated and its opening reduced in size during the rule of sultan Mohammed ben Abdallah. Bab Aghmat is east of the Jewish and Muslim cemeteries, and is near the tomb of Ali ibn Yusuf.[96] Bab Berrima with its solid towers stands near the Badi Palace.[97] Bab er Robb is a southern exit from the city, near Bab Agnaou. Built in the 12th century, it provides access to roads leading to the mountain towns of Amizmiz and Asni. Bab el Khemis—in the medina's northeastern corner, and so-called for the open-air Thursday market (Souq el Khemis)[98]—is one of the city's main gates and features a man-made spring.[99] Bab Doukkala (in the northwestern part of the city wall) is in general more massive but less ornamented than the other gates; it takes its name from Doukkala area on the Atlantic coast, well to the north of Marrakesh.[100]

Gardens

The Menara gardens are to the west of the city, at the gates of the Atlas mountains. They were built around 1130 by the Almohad ruler Abd al-Mu'min. The name menara derives from the pavilion with its small green pyramid roof (menzeh). The pavilion was built during the 16th century Saadi dynasty and renovated in 1869 by sultan Abderrahmane of Morocco, who used to stay here in summertime.[101]

.jpg)

The pavilion and a nearby artificial lake are surrounded by orchards and olive groves. The lake was created to irrigate the surrounding gardens and orchards using a sophisticated system of underground channels called a qanat. The basin is supplied with water through an old hydraulic system which conveys water from the mountains approximately 30 kilometres (19 mi) away from Marrakesh. There is also a small amphitheater and a symmetrical pool[102] where films are screened. Carp fish can be seen in the pond.[103]

The Majorelle Garden, on Avenue Yacoub el Mansour, was at one time the home of the landscape painter Jacques Majorelle. Famed designer Yves Saint Laurent bought and restored the property, which features a stele erected in his memory,[104] and the Museum of Islamic Art, which is housed in a dark blue building.[105] The garden, open to the public since 1947, has a large collection of plants from five continents including cacti, palms and bamboo.[106]

The Agdal Gardens, south of the medina and also built in the 12th century, are royal orchards surrounded by pise walls. Measuring 400 hectares (990 acres) in size, the gardens feature citrus, apricot, pomegranate, olive and cypress trees. Sultan Moulay Hassan's harem resided at the Dar al Baida pavilion, which was within these gardens.[102] This site is also known for its historic swimming pool, where a Sultan is said to have drowned.[107]

The Koutoubia Gardens are behind the Koutoubia Mosque. They feature orange and palm trees, and are frequented by storks.[102] The Mamounia Gardens, more than 100 years old and named after Prince Moulay Mamoun, have olive and orange trees as well as a variety of floral displays.[108]

In 2016, artist André Heller opened the acclaimed garden ANIMA near Ourika, which combines a large collection of plants, palms, bamboo and cacti as well as works by Keith Haring, Auguste Rodin, Hans Werner Geerdts and other artists.

Palaces and Riads

The historic wealth of the city is manifested in palaces, mansions and other lavish residences. The main palaces are El Badi Palace, the Royal Palace and Bahia Palace. Riads (Moroccan mansions) are common in Marrakesh. Based on the design of the Roman villa, they are characterized by an open central garden courtyard surrounded by high walls. This construction provided the occupants with privacy and lowered the temperature within the building.[109] Buildings of note inside the Medina are Riad Argana, Riad Obry, Riad Enija, Riad el Mezouar, Riad Frans Ankone, Dar Moussaine, Riad Lotus, Riad Elixir, Riad les Bougainvilliers, Riad Dar Foundouk, Dar Marzotto, Dar Darma, and Riad Pinco Pallino. Others of note outside the Medina area include Ksar Char Bagh, Amanjena, Villa Maha, Dar Ahlam, Dar Alhind and Dar Tayda.[110]

El Badi Palace

The El Badi Palace flanks the eastern side of the Kasbah. It was built by Saadian sultan Ahmad al-Mansur after his success against the Portuguese at the Battle of the Three Kings in 1578.[97] The lavish palace, which took around a quarter of a century to build, was funded by compensation from the Portuguese and African gold and sugar cane revenue. This allowed Carrara marble to be brought from Italy and other materials to be shipped from France, Spain and India.[97] It is a larger version of the Alhambra's Court of the Lions.[111] Although the palace is now a ruin with little left but the outer walls, the site has become the location of the annual Marrakech Folklore Festival and other events.[112]

Royal Palace

The Royal Palace, also known as Dar el-Makhzen, is next to the Badi Palace. The Almohads built the palace in the 12th century on the site of their kasba,[111] and it was partly remodeled by the Saadians in the 16th century and the Alaouites in the 17th century.[112] Historically it was one of the palaces owned by the Moroccan king,[113] who employed some of the most talented craftsmen in the city for its construction.[114][115] The palace is not open to the public, and is now privately owned by French businessman Dominique du Beldi.[112][114] The rooms are large, with unusually high ceilings for Marrakesh, with zellij (elaborate geometric terracotta tile work covered with enamel) and cedar painted ceilings.[116]

Bahia Palace

The Bahia Palace, set in extensive gardens, was built in the late 19th century by the Grand Vizier of Marrakesh, Si Ahmed ben Musa (Bou-Ahmed). Bou Ahmed resided here with his four wives, 24 concubines and many children.[117] With a name meaning "brilliance", it was intended to be the greatest palace of its time, designed to capture the essence of Islamic and Moroccan architectural styles. Bou-Ahmed paid special attention to the privacy of the palace in its construction and employed architectural features such as multiple doors which prevented passers-by from seeing into the interior.[117] The palace took seven years to build, with hundreds of craftsmen from Fez working on its wood, carved stucco and zellij.[118] The palace is set in a two-acre (8,000 m²) garden with rooms opening onto courtyards. The palace acquired a reputation as one of the finest in Morocco and was the envy of other wealthy citizens. Upon the death of Bou-Ahmed in 1900,[119] the palace was raided by Sultan Abd al-Aziz.[117]

Mosques

Koutoubia Mosque

The Koutoubia Mosque is the largest mosque in the city, in the southwest of the medina quarter of Marrakesh, within sight of the Jemaa al-Fnaa. It was completed under the reign of the Almohad Caliph Yaqub al-Mansur (1184–1199), and has inspired other buildings such as the Giralda of Seville and the Hassan Tower of Rabat. The mosque is made of red stone and brick and measures 80 metres (260 ft) long and 60 metres (200 ft) wide. The minaret is constructed from sandstone and stands 77 metres (253 ft) high. It was originally covered with Marrakshi pink plaster, but in the 1990s experts opted to remove the plaster to expose the original stone work. The spire atop the minaret is decorated with gilded copper balls that decrease in size towards the top, a style unique to Morocco.[120]

Ben Youssef Mosque

Ben Youssef Mosque, distinguished by its green tiled roof and minaret, is in the medina and is Marrakesh's oldest mosque.[121] It was originally built in the 12th century by the Almoravid Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf, whom it is named after.[122] It served as the city's main Friday mosque. After being abandoned during the Almohad period and falling into ruin, it was rebuilt in the 1560s by the Saadian sultan Abdallah al-Ghalib and then completely rebuilt again by the Alaouite sultan Moulay Sliman at the beginning of the 19th century, with construction of the minaret finishing in 1819 or 1820.[122] This reconstruction has eliminated all traces of the original mosque, and the current mosque is much smaller than the original and features a very different qibla orientation.[123][122] Abdallah al-Ghalib was also responsible for building the adjacent Ben Youssef Madrasa, which contained a library and operated as an educational institution up until the 20th century.

Almoravid Koubba

The only Almoravid-era remnant of the original mosque is the nearby Koubba Ba’adiyn, a two-storied ablutions kiosk discovered in a sunken location next to the mosque site in 1948. It demonstrates a sophisticated style and is an important piece of historical Moroccan architecture.[122] Its arches are scalloped on the first floor, while those on the second floor bear a twin horseshoe shape embellished with a turban motif. The dome of the kiosk is framed by a battlement decorated with arches and seven-pointed stars. The interior of the octagonal arched dome is decorated with distinctive carvings bordered by a Kufic frieze inscribed with the name of its patron, Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf. The squinches at the corners of the dome are covered with muqarnas.[124] The kiosk has motifs of pine cones, palms and acanthus leaves which are also replicated in the Ben Youssef Madrasa.[125]

Kasbah Mosque

The Kasbah Mosque overlooks Place Moulay Yazid in the Kasbah district of Marrakesh, close to the El Badi Palace. It was built by the Almohad caliph Yaqub al-Mansour in the late 12th century to serve as the main mosque of the kasbah (citadel) where he and his high officials resided.[122] It features a unique floor plan and courtyard layout that sets it apart from other classic Moroccan mosques. It contended with the Koutoubia Mosque for prestige and the decoration of its minaret was highly influential in subsequent Moroccan architecture.[122] The mosque was repaired by the Saadi sultan Moulay Abd Allah al-Ghalib following a devastating explosion at a nearby gunpowder reserve in the second half of the 16th century.[126] Notably, the Saadian Tombs were built just outside its qibla (southern) wall, and visitors pass behind the mosque to see them today.

Mouassine Mosque

The Mouassine Mosque (also known as the Al Ashraf Mosque) was built by the Saadian Sultan Moulay Abdallah al-Ghalib between 1562–63 and 1572–73.[127] It is in the Mouassine district and is part of a larger architectural complex which includes a library, hammam (public bathhouse), madrasa (school) and a triple arched fountain known as the Mouassine Fountain. The fountain, which provided locals with access to water, is one of the largest and most important in the city, decorated with geometric patterns and Arabic inscriptions.[127][128] Along with Bab Doukkala Mosque further west, which was built around the same time, the Mouassine Mosque appears to have been originally designed to anchor the development of new neighbourhoods after the relocation of the Jewish district from this area to the new mellah near the Kasbah.[127][129][122]

Tombs

Saadian Tombs

The Saadian Tombs were built in the 16th century as a royal necropolis for the Saadian sultans and their family members. It is next to the south wall of the Kasbah Mosque.[130] It was lost for many years until the French rediscovered it in 1917 using aerial photographs.[131] The mausoleum comprises the remains of about sixty members of the Saadi Dynasty which originated in the valley of the Draa River.[88][95] Among the tombs are those of Saadian sultan Ahmad al-Mansur and his family; al-Mansur buried his mother in this dynastic necropolis in 1590 after enlarging the original square funeral structure constructed by Abdallah al-Ghalib. His own mausoleum, richly embellished, was modeled on the Nasrid mausoleum in the Alhambra of Granada, Spain. It comprises a roof of carved and painted cedar wood supported on twelve columns of carrara marble, as well as walls covered in elaborate geometric patterns in zellij tilework, Arabic calligraphic inscriptions, and vegetal motifs in carved stucco.[130][132] The chamber also contains the graves of his close family members and some of his successors, many of which are covered with horizontal tombstones of finely carved marble.[132] His chamber is adjoined by two other rooms, the largest of which was originally a prayer room, equipped with a mihrab, which was later repurposed as a mausoleum for members of the Alaouite dynasty.[132]

Tombs of the Seven Saints

The medina holds the tombs of the seven patron saints of the city, which are visited every year by pilgrims during the week-long ziara pilgrimage. A pilgrimage to the tombs offers an alternative to the hajj to Mecca and Medina for people of western Morocco who could not visit Arabia due to the arduous and costly journey involved.[133] This ritual is performed over seven days in the following order: Sidi Yusuf ibn Ali Sanhaji, Sidi al-Qadi Iyyad al-Yahsubi, Sidi Bel Abbas, Sidi Mohamed ibn Sulayman al-Jazouli, Sidi Abdellaziz Tabba'a, Sidi Abdellah al-Ghazwani, and lastly, Sidi Abderrahman al-Suhayli.[134][135] Many of these mausoleums also serve as the focus of their own zawiyas (Sufi religious complexes with mosques), including: the Zawiya and mosque of Sidi Bel Abbes (the most important of them)[133], the Zawiya of al-Jazuli, the Zawiya of Sidi Abdellaziz, the Zawiya of Sidi Yusuf ibn Ali, and the Zawiya of Sidi al-Ghazwani (also known as Moulay el-Ksour).[28]

Mellah

The old Jewish Quarter (Mellah) is in the kasbah area of the city's medina, east of Place des Ferblantiers. It was created in 1558 by the Saadians at the site where the sultan's stables were.[136] At the time, the Jewish community consisted of a large portion of the city's bankers, jewelers, metalworkers, tailors and sugar traders. During the 16th century, the Mellah had its own fountains, gardens, synagogues and souks. Until the arrival of the French in 1912, Jews could not own property outside of the Mellah; all growth was consequently contained within the limits of the neighborhood, resulting in narrow streets, small shops and higher residential buildings. The Mellah, today reconfigured as a mainly residential zone renamed Hay Essalam, currently occupies an area smaller than its historic limits and has an almost entirely Muslim population. The Alzama Synagogue, built around a central courtyard, is in the Mellah.[137] The Jewish cemetery here is the largest of its kind in Morocco. Characterized by white-washed tombs and sandy graves,[137] the cemetery is within the Medina on land adjacent to the Mellah.[138]

Hotels

As one of the principal tourist cities in Africa, Marrakesh has over 400 hotels. Mamounia Hotel is a five-star hotel in the Art Deco-Moroccan fusion style, built in 1925 by Henri Prost and A. Marchis.[139] It is considered the most eminent hotel of the city[140][141] and has been described as the "grand dame of Marrakesh hotels." The hotel has hosted numerous internationally renowned people including Winston Churchill, Prince Charles of Wales and Mick Jagger.[141] Churchill used to relax within the gardens of the hotel and paint there.[142] The 231-room hotel,[143] which contains a casino, was refurbished in 1986 and again in 2007 by French designer Jacques Garcia.[142][141] Other hotels include Eden Andalou Hotel, Hotel Marrakech, Sofitel Marrakech, Palm Plaza Hotel & Spa, Royal Mirage Hotel, Piscina del Hotel, and Palmeraie Palace at the Palmeraie Rotana Resort.[144] In March 2012, Accor opened its first Pullman-branded hotel in Marrakech, Pullman Marrakech Palmeraie Resort & Spa. Set in a 17 hectares (42 acres) olive grove at La Palmeraie, the hotel has 252 rooms, 16 suites, six restaurants and a 535 square metres (5,760 sq ft) conference room.[145]

Culture

Museums

Marrakech Museum

The Marrakech Museum, housed in the Dar Menebhi Palace in the old city centre, was built at the end of the 19th century by Mehdi Menebhi. The palace was carefully restored by the Omar Benjelloun Foundation and converted into a museum in 1997.[146] The house itself represents an example of classical Andalusian architecture, with fountains in the central courtyard, traditional seating areas, a hammam and intricate tilework and carvings.[147] It has been cited as having "an orgy of stalactite stucco-work" which "drips from the ceiling and combines with a mind-boggling excess of zellij work."[147] The museum holds exhibits of both modern and traditional Moroccan art together with fine examples of historical books, coins and pottery produced by Moroccan Jewish, Berber and Arab peoples.[148][149]

Dar Si Said Museum

Dar Si Said Museum, also known as the Museum of Moroccan Arts is to the north of the Bahia Palace. It was the mansion of Si Said, brother to Grand Vizier Ba Ahmad, and was constructed at the same time as Ahmad's own Bahia Palace. The collection of the museum is considered to be one of the finest in Morocco, with "jewellery from the High Atlas, the Anti Atlas and the extreme south; carpets from the Haouz and the High Atlas; oil lamps from Taroudannt; blue pottery from Safi and green pottery from Tamgroute; and leatherwork from Marrakesh."[117] Among its oldest and most significant artifacts is an early 11th-century marble basin from the late caliphal period of Cordoba, Spain.[150]

Museum of Islamic Art

The Museum of Islamic Art (Musée d'Art Islamique) is a blue-coloured building in the Marjorelle Gardens. The private museum was created by Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé in the home of Jacques Majorelle,[111] who had his art studio there. Recently renovated, its small exhibition rooms have displays of Islamic artifacts and decorations including Irke pottery, polychrome plates, jewellery, and antique doors.[151][152]

Music, theatre and dance

Two types of music are traditionally associated with Marrakesh. Berber music is influenced by Andalusian classical music and typified by its oud accompaniment. By contrast, Gnaoua music is loud and funky with a sound reminiscent of the Blues. It is performed on handmade instruments such as castanets, ribabs (three-stringed banjos) and deffs (handheld drums). Gnaoua music's rhythm and crescendo take the audience into a mood of trance; the style is said to have emerged in Marrakesh and Essaouira as a ritual of deliverance from slavery.[153] More recently, several Marrakesh female music groups have also risen to popularity.[154]

The Théâtre Royal de Marrakesh, the Institut Français and Dar Chérifa are major performing arts institutions in the city. The Théâtre Royal, built by Tunisian architect Charles Boccara, puts on theatrical performances of comedy, opera, and dance in French and Arabic.[155] A greater number of theatrical troupes perform outdoors and entertain tourists on the main square and the streets, especially at night. Christopher Hudson of the Daily Mail noted that "men dressed as women performed bawdy street theatre, to the delight of a ring of onlookers of all ages."[156]

Crafts

The arts and crafts of Marrakesh have had a wide and enduring impact on Moroccan handicrafts to the present day. Riad décor is widely used in carpets and textiles, ceramics, woodwork, metal work and zelij. Carpets and textiles are weaved, sewn or embroidered, sometimes used for upholstering. Moroccan women who practice craftsmanship are known as Maalems (expert craftspeople) and make such fine products as Berber carpets and shawls made of sabra (cactus silk).[154] Ceramics are in monochrome Berber-style only, a limited tradition depicting bold forms and decorations.[154]

Wood crafts are generally made of cedar, including the riad doors and palace ceilings. Orange wood is used for making ladles known as harira (lentil soup ladles). Thuya craft products are made of caramel coloured thuya, a conifer indigenous to Morocco. Since this species is almost extinct, these trees are being replanted and promoted by the artists' cooperative Femmes de Marrakech.[154]

Metalwork made in Marrakesh includes brass lamps, iron lanterns, candle holders made from recycled sardine tins, and engraved brass teapots and tea trays used in the traditional serving of tea. Contemporary art includes sculpture and figurative paintings. Blue veiled Tuareg figurines and calligraphy paintings are also popular.[154]

Festivals

Festivals, both national and Islamic, are celebrated in Marrakesh and throughout the country, and some of them are observed as national holidays.[157] Cultural festivals of note held in Marrakesh include the National Folklore Festival, the Marrakech Festival of Popular Arts (in which a variety of famous Moroccan musicians and artists participate), international folklore festival Marrakech Folklore Days and the Berber Festival.[157][158] The International Film Festival of Marrakech, which aspires to be the North African version of the Cannes Film Festival, was established in 2001.[159] The festival, which showcases over 100 films from around the world annually, has attracted Hollywood stars such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Susan Sarandon, Jeremy Irons, Roman Polanski and many European, Arabic and Indian film stars.[159] The Marrakech Bienniale was established in 2004 by Vanessa Branson as a cultural festival in various disciplines, including visual arts, cinema, video, literature, performing arts, and architecture.[160]

Food

Surrounded by lemon, orange, and olive groves, the city's culinary characteristics are rich and heavily spiced but not hot, using various preparations of Ras el hanout (which means "Head of the shop"), a blend of dozens of spices which include ash berries, chilli, cinnamon, grains of paradise, monk's pepper, nutmeg, and turmeric.[161] A specialty of the city and the symbol of its cuisine is tanjia marrakshia a local tajine prepared with beef meat, spices and "smen" and slow-cooked in a traditional oven in hot ashes.[162] Tajines can be prepared with chicken, lamb, beef or fish, adding fruit, olives and preserved lemon, vegetables and spices, including cumin, peppers, saffron, turmeric, and ras el hanout. The meal is prepared in a tajine pot and slow-cooked with steam. Another version of tajine includes vegetables and chickpeas seasoned with flower petals.[163] Tajines may also be basted with "smen" moroccan ghee that has a flavour similar to blue cheese.[164]

Shrimp, chicken and lemon-filled briouats are another traditional specialty of Marrakesh. Rice is cooked with saffron, raisins, spices, and almonds, while couscous may have added vegetables. A pastilla is a filo-wrapped pie stuffed with minced chicken or pigeon that has been prepared with almonds, cinnamon, spices and sugar.[165] Harira soup in Marrakesh typically includes lamb with a blend of chickpeas, lentils, vermicelli, and tomato paste, seasoned with coriander, spices and parsley. Kefta (mince meat), liver in crépinette, merguez and tripe stew are commonly sold at the stalls of Jemaa el-Fnaa.[166]

The desserts of Marrakesh include chebakia (sesame spice cookies usually prepared and served during Ramadan), tartlets of filo dough with dried fruit, or cheesecake with dates.[167]

The Moroccan tea culture is practiced in Marrakesh; green tea with mint is served with sugar from a curved teapot spout into small glasses.[168] Another popular non-alcoholic drink is orange juice.[169] Under the Almoravids, alcohol consumption was common;[170] historically, hundreds of Jews produced and sold alcohol in the city.[171] In the present day, alcohol is sold in some hotel bars and restaurants.[172]

Education

Marrakesh has several universities and schools, including Cadi Ayyad University (also known as the University of Marrakech), and its component, the École nationale des sciences appliquées de Marrakech (ENSA Marrakech), which was created in 2000 by the Ministry of Higher Education and specializes in engineering and scientific research, and the La faculté des sciences et techniques-gueliz which known to be number one in Morocco in its kind of faculties. [173][174] Cadi Ayyad University was established in 1978 and operates 13 institutions in the Marrakech Tensift Elhaouz and Abda Doukkala regions of Morocco in four main cities, including Kalaa of Sraghna, Essaouira and Safi in addition to Marrakech.[175] Sup de Co Marrakech, also known as the École Supérieure de Commerce de Marrakech, is a private four-year college that was founded in 1987 by Ahmed Bennis. The school is affiliated with the École Supérieure de Commerce of Toulouse, France; since 1995 the school has built partnership programs with numerous American universities including the University of Delaware, University of St. Thomas, Oklahoma State University, National-Louis University, and Temple University.

Ben Youssef Madrasa

.jpg)

The Ben Youssef Madrasa, north of the Medina, was an Islamic college in Marrakesh named after the Almoravid sultan Ali ibn Yusuf (1106–1142) who expanded the city and its influence considerably. It is the largest madrasa in all of Morocco and was one of the largest theological colleges in North Africa, at one time housing as many as 900 students.[176]

The college, which was affiliated with the neighbouring Ben Youssef Mosque, was founded during the Marinid dynasty in the 14th century by Sultan Abu al-Hassan.[176]

This education complex specialized in Quranic law and was linked to similar institutions in Fez, Taza, Salé, and Meknes.[124] The Madrasa was re-constructed by the Saadian Sultan Abdallah al-Ghalib (1557–1574) in 1564 as the largest and most prestigious madrasa in Morocco.[124] The construction ordered by Abdallah al-Ghalib was completed in 1565, as attested by the inscription in the prayer room.[177] Its 130 student dormitory cells cluster around a courtyard richly carved in cedar, marble and stucco. In accordance with Islam, the carvings contain no representation of humans or animals, consisting entirely of inscriptions and geometric patterns. One of the school's best known teachers was Mohammed al-Ifrani (1670–1745). After a temporary closure beginning in 1960, the building was refurbished and reopened to the public as a historical site in 1982.[178]

Sports

Football clubs based in Marrakesh include Najm de Marrakech, KAC Marrakech, Mouloudia de Marrakech and Chez Ali Club de Marrakech. The city contains the Circuit International Automobile Moulay El Hassan a race track which hosts the World Touring Car Championship and from 2017 FIA Formula E. The Marrakech Marathon is also held here.[179] Roughly 5000 runners turn out for the event annually.[180] Also, here takes place Grand Prix Hassan II tennis tournament (on clay) part of ATP World Tour series.

Golf is a popular sport in Marrakech. The city has three golf courses just outside the city limits and played almost through the year. The three main courses are the Golf de Amelikis on the road to Ourazazate, the Palmeraie Golf Palace near the Palmeraie, and the Royal Golf Club, the oldest of the three courses.[181]

Transport

Rail

The Marrakesh railway station is linked by several trains running daily to other major cities in Morocco such as Casablanca, Tangiers, Fez, Meknes and Rabat. The Casablanca–Tangier high-speed rail line opened in November 2018.[182]

In 2015, a tramway is proposed.

Road

The main road network within and around Marrakesh is well paved. The major highway connecting Marrakesh with Casablanca to the south is A7, a toll expressway, 210 km (130 mi) in length. The road from Marrakesh to Settat, a 146 km (91 mi) stretch, was inaugurated by King Mohammed VI in April 2007, completing the 558 km (347 mi) highway to Tangiers. Highway A7 connects also Marrakesh to Agadir, 233 km (145 mi) to the south-west.[182]

Air

The Marrakesh-Menara Airport (RAK) is 3 km (1.9 mi) southwest of the city centre. It is an international facility that receives several European flights as well as flights from Casablanca and several Arab nations.[183] The airport is at an elevation of 471 metres (1,545 ft) at 31°36′25″N 008°02′11″W.[184] It has two formal passenger terminals, but these are more or less combined into one large terminal. A third terminal is being built.[185] The existing T1 and T2 terminals offer a space of 42,000 m2 (450,000 sq ft) and have a capacity of 4.5 million passengers per year. The blacktopped runway is 4.5 km (2.8 mi) long and 45 m (148 ft) wide. The airport has parking space for 14 Boeing 737 and four Boeing 747 aircraft. The separate freight terminal has 340 m2 (3,700 sq ft) of covered space.[186]

Healthcare

Marrakesh has long been an important centre for healthcare in Morocco, and the regional rural and urban populations alike are reliant upon hospitals in the city. The psychiatric hospital installed by the Merinid Caliph Ya'qub al-Mansur in the 16th century was described by the historian 'Abd al-Wahfd al- Marrakushi as one of the greatest in the world at the time.[187] A strong Andalusian influence was evident in the hospital, and many of the physicians to the Caliphs came from places such as Seville, Zaragoza and Denia in eastern Spain.[187]

A severe strain has been placed upon the healthcare facilities of the city in the last decade as the city population has grown dramatically.[188] Ibn Tofail University Hospital is one of the major hospitals of the city.[189] In February 2001, the Moroccan government signed a loan agreement worth eight million U.S. dollars with The OPEC Fund for International Development to help improve medical services in and around Marrakesh, which led to expansions of the Ibn Tofail and Ibn Nafess hospitals. Seven new buildings were constructed, with a total floor area of 43,000 square metres (460,000 sq ft). New radiotherapy and medical equipment was provided and 29,000 square metres (310,000 sq ft) of existing hospital space was rehabilitated.[188]

In 2009, king Mohammed VI inaugurated a regional psychiatric hospital in Marrakesh, built by the Mohammed V Foundation for Solidarity, costing 22 million dirhams (approximately 2.7 million U.S. dollars).[190] The hospital has 194 beds, covering an area of 3 hectares (7.4 acres).[190] Mohammed VI has also announced plans for the construction of a 450 million dirham military hospital in Marrakesh.[191]

Gallery

The Boarding Area inside Marrakesh Airport.

The Boarding Area inside Marrakesh Airport.- Marrakesh Menara Mall is a mall in Marrakesh.

- A Traditional house in Marrakesh a Riad.

.jpg) American School of Marrakesh.

American School of Marrakesh..jpg) Koutoubia Mosque, Marrakesh

Koutoubia Mosque, Marrakesh Jemaa el-Fnaa at night, Marrakesh.

Jemaa el-Fnaa at night, Marrakesh.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Marrakesh is twinned with:

See also

- List of people from Marrakesh

- Marrakesh in popular culture

References

- "Présidences des communes: des résultats sans surprises". medias24.com (in French). Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- "Morocco Population Census - Marrakesh (مراكش)". High Commission for Planning. 19 March 2015. p. 7. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- "Note de présentation des premiers résultats du Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitat 2014" (in French). High Commission for Planning. 20 March 2015. p. 8. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "Marrakech or Marrakesh". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Nanjira 2010, p. 208.

- "Medina of Marrakesh". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Shillington 2005, p. 948.

- Searight 1999, p. 378.

- Egginton & Pitz 2010, p. 11.

- Bosworth 1989, p. 588.

- Cornell 1998, p. 15.

- Bosworth 1989, p. 593.

- Gottreich 2007, p. 10.

- International Business Publications (1 April 2006). Morocco Country Study Guide. International Business Publications. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7397-1514-7. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- Rogerson & Lavington 2004, p. xi.

- Messier 2010, p. 180.

- Naylor 2009, p. 90.

- Gerteiny 1967, p. 28.

- The Rotarian. Rotary International. July 2005. p. 14. ISSN 0035-838X. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- Lehmann, Henss & Szerelmy 2009, p. 292.

- "Moroccan Resurgence: Wealth and the World Come to Tangier". Spiegel Online. 2007-11-09. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

- Barrows 2004, p. 85.

- Cenival (1913–38: p.300; 2007: p.324)

- Lehmann, Henss & Szerelmy 2009, p. 57.

- Orange Coast Magazine. Emmis Communications. February 1996. p. 46. ISSN 0279-0483. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "The Patron Saints of Marrakech". Dar-Sirr.com. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Bosworth 1989, p. 591.

- Wilbaux, Quentin (2001). La médina de Marrakech: Formation des espaces urbains d'une ancienne capitale du Maroc. Paris: L'Harmattan. pp. 107–109. ISBN 2747523888.

- Loizillon 2008, p. 50.

- Chisholm, Hugh, General Editor. Entry for 'Marrakesh'. 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica (1910).

- Bibliographic Set (2 Vol Set). International Court of Justice, Digest of Judgments and Advisory Opinions, Canon and Case Law 1946 – 2011. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 117. ISBN 978-90-04-23062-0. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- Barrows 2004, p. 73.

- Lehmann, Henss & Szerelmy 2009, p. 84.

- Hoisington 2004, p. 109.

- Christiani 2009, p. 38.

- MEED. Economic East Economic Digest, Limited. 1971. p. 324. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Sullivan 2006, p. 8.

- Howe 2005, p. 46.

- Shackley 2012, p. 43.

- "Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organization (with final act, annexes and protocol). Concluded at Marrakesh on 15 April 1994" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (pdf) on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- Academie de droit 2002, p. 71.

- "MARRAKECH: Dozens of heads of State and Government to attend UN climate conference". United Nations. 13 November 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- "Construction Begins on Venue of COP22 in Marrakech | UNFCCC". unfccc.int. 12 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2019. Content is copied from this source, which is © 2019 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Reuse is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged.

- "Morocco: Marrakesh bomb strikes Djemaa el-Fna square". BBC. 28 April 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "Qaeda denies involvement in Morocco cafe bomb attack". Reueters. 7 May 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- Maps (Map). Google Maps.

- Clark 2012, pp. 11–13.

- Searight 1999, p. 407.

- Rogerson & Lavington 2004, p. 49.

- Lehmann, Henss & Szerelmy 2009, p. 310.

- "Marrakech (Marrakesh) Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Barrows 2004, p. 74.

- "Marrakesh, Morocco - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "Klimatafel von Marrakech / Marokko" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- "Station Menara" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- 2014 Morocco Population Census

- "Recensement général de la population et de l'habitat de 2004" (PDF). Haut-commissariat au Plan, Lavieeco.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "WORLD TRAVEL: Africa's beating heart; Marrakech, no longer a hippy paradise, is still a vital centre of economy and culture in Morocco". The Birmingham Post via Questia Online Library. 2 September 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Duncan, Fiona. "The best Marrakesh hotels". The Telegraph. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "Marrakech is the new Costa del Sol: for a host of Western celebrities, Marrakech in Morocco has become the place to be seen at and increasingly, to live in. Where celebrities go, the lesser folk are bound to follow. The result is that Morocco's economy and its culture is changing—but for the better or for the worse?". African Business via Questia Online Library. 1 March 2005. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "Fatima Zahra Mansouri, première dame de Marrakech". Jeune Afrique (in French). 25 January 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "La reprise de la croissance du secteur immobilier à Marrakech" (in French). Regiepresse.co. 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- "Marrakech, Morocco Sees Hotel Boom". Huffington Post. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- "Royal Ranches Marrakech' closes land sale with Equine Management Services". Mena Report via HighBeam Research (subscription required). 2 October 2008. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "Bahrain : Royal Ranches Marrakech inks MoU with BMCE.(Memorandum of Understanding )(Banque Marocaine de Commerce Exteriur)". Mena Report via HighBeam Research (subscription required). 13 April 2012. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Humphrys 2010, p. 9.

- Misc. (1 June 2008). Cool Restaurants Top of the World. teNeues. p. 274. ISBN 978-3-8327-9233-6. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- Humphrys 2010, p. 161.

- The Report: Morocco 2011. Oxford Business Group. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-907065-30-9. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- "Nos usines et centres L'usine de Marrakech" (in French). Ciments du Maroc. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Bergin, Daniel; Nijman, Vincent (2014-11-01). "Open, Unregulated Trade in Wildlife in Morocco's Markets". ResearchGate. 26 (2).

- Nijman, Vincent; Bergin, Daniel; Lavieren, Els van (2015-07-01). "Barbary macaques exploited as photo-props in Marrakesh's punishment square". ResearchGate. Jul-Sep.

- Nijman, V. and Bergin, D. (2017). "Trade in spur-Thighed tortoises Testudo graeca in Morocco: Volumes, value and variation between markets". Amphibia-Reptilia.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bergin, D. and Nijman, V. (2018). "An Assessment of Welfare Conditions in Wildlife Markets across Morocco". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "L'Organisation Judicaire" (in French). Le Ministère de la Justice. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- "Adresses Utiles" (in French). Chambre de Commerce, D'Industrie et des Services de Marrakech. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- "Morocco's Marrakech elects first woman mayor". Al Arabiya (Saudi Arabia) via HighBeam Research (subscription required). 21 June 2009. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "Biography of Fatima Zahra MANSOURI". African Success. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- "Morocco mayor's unseating prompts strike calls". Al Arabiya (Saudi Arabia) via HighBeam Research (subscription required). 14 July 2009. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.