Bruneian Empire

The Bruneian Empire or Empire of Brunei (/bruːˈnaɪ/ brew-NYE), also known as Sultanate of Brunei, was a Malay sultanate, centred in Brunei on the northern coast of Borneo island in Southeast Asia. Bruneian rulers converted to Islam around the 15th century, when it grew substantially since the fall of Malacca to the Portuguese,[3][4] extending throughout coastal areas of Borneo and the Philippines, before it declined in the 17th century.[5]

Empire of Brunei Bruneian Sultanate Empayar Brunei | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1368–1888 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||||||||||||||

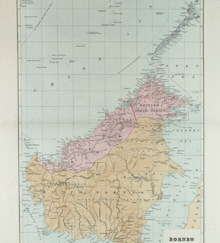

.png) The extent of the Bruneian Empire in the 16th century | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Tributary of the Ming Empire (1370-1425) Sovereign state (1425-1888) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kota Batu Kampong Ayer Brunei Town[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Brunei Malay, Old Malay, Old Tagalog, Arabic and Bornean languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sultan (until last empire) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1368–1402 | Sultan Muhammad Shah | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1425–1432 | Sharif Ali | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1485–1524 | Bolkiah | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1582–1598 | Muhammad Hassan | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1828–1852 | Omar Ali Saifuddin II | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1885–1906[2] | Hashim Jalilul Alam Aqamaddin | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• Sultanate established | 1368 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1888 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Barter, Cowrie, Piloncitos, and later Brunei pitis | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Brunei | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-Sultanate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Historiography

Understanding the history of the Bruneian Empire is quite difficult since it is hardly mentioned in contemporary sources of its time, as well as there being a scarcity of evidence of its nature. No local or indigenous sources exist to provide evidence for any of this. As a result, Chinese texts have been relied on to construct the history of early Brunei.[6] Boni in Chinese sources most likely refers to Borneo as a whole, while Poli 婆利, probably located in Sumatra, is claimed by local authorities to refer to Brunei as well.[7]

History

Pre-empire history

The earliest diplomatic relations between Boni (渤泥) and China are recorded in the Taiping Huanyu Ji (太平環宇記) (978).[7] In 1178, a mission to China sent by Srivijaya include forest product from Borneo such as plum flower-shaped Borneo camphor planks, which highlighted the Srivijaya's role as intermediary to acquire Borneo product.[8] In 1225, a Song dynasty official, Zhao Rukuo, reported that Boni had 10,000 population who populated a city surrounded by a timber wall, and having 150 warships to protect its trade, and that there was a lot of wealth in the kingdom.[8][9] Zhao Rukuo noted that smaller riverine systems in Borneo are traded with Boni in smaller vessel; they are Xi Fenggong (River Serudong), Shimiao (Sibu), Hulumandou (Martapura) and Suwulu (Matan). These are sub-regional port of Borneo network located in west and south coast of Borneo.[8]

In the 14th century, Brunei seems to be subjected to Java. The Javanese manuscript Nagarakretagama, written by Prapanca in 1365, mentioned Barune as the vassal state of Majapahit,[10] which had to make an annual tribute of 40 katis of camphor.

Early empire

In 1369, the Sulus attacked Po-ni, looting it of treasure and gold. A fleet from Majapahit succeeded in driving away the Sulus, but Po-ni was left weaker after the attack.[11] A Chinese report from 1371 described Po-ni as poor and totally controlled by Majapahit.[12]

Expansion

After the death of its emperor, Hayam Wuruk, Majapahit entered a state of decline and was unable to control its overseas possessions. This opened the opportunity for Bruneian kings to expand their influence.

In 1370, Brunei received an imperial emissary from the Ming Empire, which sought to re-establish the Song dynasty tributary system.[13] In 1371, Brunei established a tributary relationship with the Ming.[13]:41 During the 1370 visit, Ming observers noted the Islamisation of Brunei to be limited to only a section of the royal entourage, while Buddhism was spreading in the general populace.[13] Despite the establishment of Ming suzerainty, Brunei did not pay much attention to Ming decrees until 1403, when the Yongle Emperor rapidly strengthened among maritime trade policies.[13] Brunei ceased to be a tributary state of the Ming in 1425.[14]

By the 15th century, the empire became a Muslim state, when the King of Brunei converted to Islam, brought by Muslim Indians and Arab merchants from other parts of Maritime Southeast Asia, who came to trade and spread Islam.[15][16] It controlled most of northern Borneo, and it became an important hub for the East and Western world trading system.[17] Local historians assume that the Bruneian empire was a thalassocratic empire that was based upon maritime power, which means its influence was confined to coastal towns, ports and river estuaries, and seldom penetrated deep into the interior of the island. The Bruneian kings seem to have cultivated alliance with regional seafaring peoples of Orang Laut and Bajau that formed their naval armada. The Dayaks, native tribes of interior Borneo however, were not under their control, as imperial influence seldom penetrated deep into the jungles.

Following the presence of Portuguese after the fall of Malacca, Portuguese merchants traded regularly with Brunei from 1530 and described the capital of Brunei as surrounded by a stone wall.[3][18]

During the rule of Bolkiah, the fifth Sultan, the empire held control over coastal areas of northwest Borneo (present-day Brunei, Sarawak and Sabah) and reached Seludong (present-day Manila), Sulu Archipelago including parts of the island of Mindanao.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] In the 16th century, the Brunei empire's influence extended as far as Kapuas River delta in West Kalimantan. The Malay Sultanate of Sambas in West Kalimantan and Sultanate of Sulu in Southern Philippines in particular developed dynastic relations with the royal house of Brunei. Other Malay sultans of Pontianak, Samarinda as far as Banjarmasin, treated the Sultan of Brunei as their leader. The true nature of Brunei's relations to other Malay Sultanates of coastal Borneo and Sulu archipelago is still a subject of study, as to whether it was a vassal state, an alliance, or just a ceremonial relationship. Other regional polities also exercised their influence upon these sultanates. The Sultanate of Banjar (present-day Banjarmasin) for example, was also under the influence of Demak in Java.

Decline

.gif)

By the end of 17th century, Brunei entered a period of decline brought on by internal strife over royal succession, colonial expansion of the European powers, and piracy.[5] The empire lost much of its territory due to the arrival of the western powers such as the Spanish in the Philippines, the Dutch in southern Borneo and the British in Labuan, Sarawak and North Borneo. By 1725, Brunei had many of its supply routes had been taken over by the Sulu Sultanate.[13]:73

In 1888, Sultan Hashim Jalilul Alam Aqamaddin later appealed to the British to stop further encroachment.[27] In the same year British signed a "Treaty of Protection" and made Brunei a British protectorate[5] until 1984 when it gained independence.[28][29]

Government

The Government of Bruneian Empire was democratic in nature. The empire was divided into three traditional land systems known as Kerajaan (Crown Property), Kuripan (official property) and Tulin (hereditary private property).[30]

References

Citations

- Hussainmiya 2010, pp. 67.

- Yunos 2008.

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, pp. 129.

- Andaya & Andaya 2015, pp. 159.

- CIA Factbook 2017.

- Jamil Al-Sufri 2000.

- Kurz 2014, pp. 1.

- Aung-Thwin, Michael Arthur; Hall, Kenneth R. (13 May 2011). New Perspectives on the History and Historiography of Southeast Asia: Continuing Explorations. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-81964-3.

- History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 43.

- Suyatno 2008.

- History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 44.

- History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 45.

- de Vienne, Marie-Sybille (2015). Brunei: From the Age of Commerce to the 21st Century. National University of Singapore Press. pp. 39–74.

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2011). History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 91–93.

- Awang Abdul Aziz bin Awang Juned 1992.

- Saunders 2013, pp. 23.

- Oxford Business Group 2011, pp. 179.

- Lach 1994, pp. 580.

- Saunders 2013, pp. 60.

- Herbert & Milner 1989, pp. 99.

- Lea & Milward 2001, pp. 16.

- Hicks 2007, pp. 34.

- Church 2012, pp. 16.

- Eur 2002, pp. 203.

- Abdul Majid 2007, pp. 2.

- Welman 2013, pp. 8.

- World Atlas 2017.

- Abdul Majid 2007, pp. 4.

- Sidhu 2009, pp. 92.

- McArthur & Horton 1987, p. 102.

Sources

- Holt, P. M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 2A, The Indian Sub-Continent, South-East Asia, Africa and the Muslim West. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brunei Museum Journal (1986). The Brunei Museum Journal. The Museum of Brunei Darussalam.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McArthur, M.S.H.; Horton, A.V.M. (1987). Report on Brunei in 1904. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies, Center for Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 0-896-80135-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Herbert, Patricia; Milner, Anthony Crothers (1989). South-East Asia: Languages and Literatures : a Select Guide. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1267-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jamil Al-Sufri, Awang Mohd. Zain (1990). Tarsilah Brunei: sejarah awal dan perkembangan Islam (in Malay). Department of Historical Centre of Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports of Brunei Darussalam.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Awang Abdul Aziz bin Awang Juned (1992). Islam di Brunei: zaman pemerintahan Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Paduka Seri Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu'izzuddin Waddaulah, Sultan dan Yang Di-Pertuan Negara Brunei Darussalam (in Malay). Department of History of Brunei Darussalam.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lach, Donald F. (1994). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I: The Century of Discovery. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-46732-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jamil Al-Sufri, Awang Mohd. Zain (2000). Tarsilah Brunei: The Early History of Brunei Up to 1432 AD. Department of Historical Centre of Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports of Brunei Darussalam. ISBN 978-99917-34-03-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lea, David; Milward, Colette (2001). A Political Chronology of South-East Asia and Oceania. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-85743-117-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eur (2002). The Far East and Australasia 2003. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bala, Bilcher (2005). Thalassocracy: a history of the medieval Sultanate of Brunei Darussalam. School of Social Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah. ISBN 978-983-2643-74-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hicks, Nigel (2007). The Philippines. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84537-663-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abdul Majid, Harun (2007). Rebellion in Brunei: The 1962 Revolt, Imperialism, Confrontation and Oil. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-423-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yunos, Rozan (2008). "The Sultan who thwarted Rajah Brooke". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Suyatno (2008). "Naskah Nagarakretagama" (in Indonesian). National Library of Indonesia. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- History for Brunei Darussalam: Sharing our Past. Curriculum Development Department, Ministry of Education of Brunei Darussalam. 2009. ISBN 99917-2-372-2.

- Sidhu, Jatswan S. (2009). Historical Dictionary of Brunei Darussalam. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7078-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hussainmiya, B. A. (2010). "The Malay Identity in Brunei Darussalam and Sri Lanka" (PDF). Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oxford Business Group (2011). The Report: Sabah. Oxford Business Group. ISBN 978-1-907065-36-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Church, Peter (2012). A Short History of South-East Asia. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-35044-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saunders, Graham (2013). A History of Brunei. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-87401-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Welman, Frans (2013). Borneo Trilogy Brunei: Vol 1. Booksmango. ISBN 978-616-222-235-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2014). "Boni in Chinese Sources: Translations of Relevant Texts from the Song to the Qing Dynasties" (PDF). Universiti Brunei Darussalam. National University of Singapore. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Y. (2015). A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400–1830. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88992-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- CIA Factbook (2017). "The World Factbook – Brunei". Central Intelligence Agency.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- World Atlas (2017). "Brunei Darussalam". World Atlas.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)