Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands (Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande) was the name for the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of the Holy Roman Empire in the Low Countries held in personal union by the Spanish Crown (also called Habsburg Spain). This region comprised most of the modern states of Belgium and Luxembourg, as well as parts of northern France, southern Netherlands, and western Germany with the capital being Brussels.

Spanish Netherlands | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1556–1714 | |||||||||||

Flag

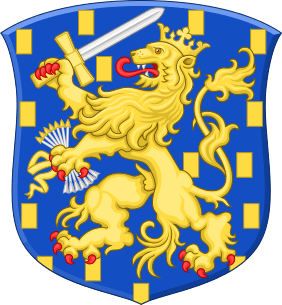

Coat of arms of Archduke Albert VII of Austria

| |||||||||||

Motto: Plus Ultra "Further Beyond" | |||||||||||

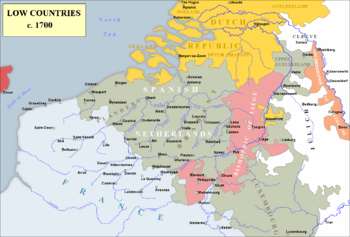

Spanish Netherlands (grey) in 1700 | |||||||||||

| Status | Province of the Spanish Empire States of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||||

| Capital | Brussels | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Dutch, French, German, Latin, Spanish, Low Saxon, West Frisian, Walloon, Luxembourgish, | ||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (State religion) Protestantism | ||||||||||

| Government | Governorate | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1581–1592 | Alexander Farnese (first) | ||||||||||

• 1692–1706 | Maximilian Emanuel (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern | ||||||||||

| 1556 | |||||||||||

| 1568–1648 | |||||||||||

| 30 January 1648 | |||||||||||

| 1683–1684 | |||||||||||

| 15 August 1684 | |||||||||||

| 1688–1697 | |||||||||||

| 1701–1714 | |||||||||||

| 7 March 1714 | |||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1700 | 1,794,000[1] | ||||||||||

| Currency | Gulden | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

The Imperial fiefs of the former Burgundian Netherlands had been inherited by the Austrian House of Habsburg from the extinct House of Valois-Burgundy upon the death of Mary of Burgundy in 1482. The Seventeen Provinces formed the core of the Habsburg Netherlands which passed to the Spanish Habsburgs upon the abdication of Emperor Charles V in 1556. When part of the Netherlands separated to form the autonomous Dutch Republic in 1581, the remainder of the area stayed under Spanish rule until the War of the Spanish Succession.

History

Background

A common administration of the Netherlandish fiefs, centred in the Duchy of Brabant, already existed under the rule of the Burgundian duke Philip the Good with the implementation of a stadtholder and the first convocation of the States General of the Netherlands in 1464.[2] His granddaughter Mary had confirmed a number of privileges to the States by the Great Privilege signed in 1477.[3] After the government takeover by her husband Archduke Maximilian I of Austria, the States insisted on their privileges, culminating in a Hook rebellion in Holland and Flemish revolts. Maximilian prevailed with the support of Duke Albert III of Saxony and his son Philip the Handsome, husband of Joanna of Castile, could assume the rule over the Habsburg Netherlands in 1493.

Philip as well as his son and successor Charles V retained the title of a "Duke of Burgundy" referring to their Burgundian inheritance, notably the Low Countries and the Free County of Burgundy in the Holy Roman Empire. The Habsburgs often used the term Burgundy to refer to their hereditary lands (e.g. in the name of the Imperial Burgundian Circle established in 1512), actually until 1795, when the Austrian Netherlands were lost to the French Republic. The Governor-general of the Netherlands was responsbile for the administration of the Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries. Charles V was born and raised in the Low Countries and often stayed at the Palace of Coudenberg in Brussels.

By the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, Charles V declared the Seventeen Provinces a united and indivisible Habsburg dominion. Between 1555 and 1556, the House of Habsburg split into an Austro-German and a Spanish branch as a consequence of Charles' abdications of Brussels. The Netherlands were left to of his son Philip II of Spain, while his brother Archduke Ferdinand I succeeded him as Holy Roman Emperor. The Seventeen Provinces, de jure still fiefs of the Holy Roman Empire, from that time on de facto were ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs as part of the Burgundian heritage.

Eighty Years' War

Philip's stern Counter-Reformation measures sparked the Dutch Revolt in the mainly Calvinist Netherlandish provinces, which led to the outbreak of the Eighty Years' War in 1568. In January 1579 the seven northern provinces formed the Protestant Union of Utrecht, which declared independence from the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands by the 1581 Act of Abjuration. The Spanish branch of the Habsburgs could retain the rule only over the partly Catholic Southern Netherlands, completed after the Fall of Antwerp in 1585.

Obv: Portraits of Albert and Isabella.

Rev: Eagle holding balance, date 1612.

Better times came, when in 1598 the Spanish Netherlands passed to Philip's daughter Isabella Clara Eugenia and her husband Archduke Albert VII of Austria.The couple's rule brought a period of much-needed peace and stability to the economy, which stimulated the growth of a separate South Netherlandish identity and consolidated the authority of the House of Habsburg reconciling previous anti-Spanish sentiments. In the early 17th century, there was a flourishing court at Brussels. Among the artists who emerged from the court of the "Archdukes", as they were known, was Peter Paul Rubens. Under Isabella and Albert, the Spanish Netherlands actually had formal independence from Spain, but always remained unofficially within the Spanish sphere of influence. With Albert's death in 1621 they returned to formal Spanish control, although the childless Isabella remained on as Governor until her death in 1633.

The failing wars intended to regain the 'heretical' northern Netherlands meant significant loss of (still mainly Catholic) territories in the north, which was consolidated in 1648 in the Peace of Westphalia, and given the peculiar inferior status of Generality Lands (jointly ruled by the United Republic, not admitted as member provinces): Zeelandic Flanders (south of the river Scheldt), the present Dutch province of Noord-Brabant and Maastricht (in the present-day Dutch province of Limburg).

French conquests

As the power of the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs waned in the latter decades of the 17th century, the territory of the Netherlands under Habsburg rule was repeatedly invaded by the French and an increasing portion of the territory came under French control in successive wars. By the Treaty of the Pyrenees of 1659 the French annexed Artois and Cambrai, and Dunkirk was ceded to the English. By the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (ending the War of Devolution in 1668) and Nijmegen (ending the Franco-Dutch War in 1678), further territory up to the current Franco-Belgian border was ceded, including Walloon Flanders, as well as half of the county of Hainaut (including Valenciennes). Later, in the War of the Reunions and the Nine Years' War, France annexed other parts of the region.

During the War of the Spanish Succession, in 1706 the Habsburg Netherlands became an Anglo-Dutch condominium for the remainder of the conflict.[4] By the peace treaties of Utrecht and Rastatt in 1713/14 ending the war, the Southern Netherlands returned to the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy forming the Austrian Netherlands.

Provinces

From 1581 the Habsburg Netherlands consisted of the following territories, all part of modern Belgium unless otherwise stated:

- the Duchy of Brabant, except for North Brabant part of the Generality Lands of the Dutch Republic in 1648, including the former Margraviate of Antwerp (now mostly Belgium, some in Netherlands)

- the Duchy of Limburg, except for Limburg of the States part of the Dutch Generality Lands from 1648

- the Duchy of Luxembourg, a sovereign state from 1815 (parts in modern Belgium, France and Germany)

- the Upper Quarter (Bovenkwartier) of the Duchy of Guelders (Now Netherlands and Germany: the area around Venlo and Roermond, in the present Dutch province of Limburg, and the town of Geldern in the present German district of Kleve)

- the County of Artois, ceded to France by the 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees (now in France)

- the County of Flanders, except for Zeelandic Flanders part of the Dutch Generality Lands from 1648, Walloon Flanders ceded to France by the 1678 Peace of Nijmegen (now in Belgium and France French Flanders)

- the County of Namur

- the County of Hainaut, southern part with Valenciennes ceded to France by the 1678 Peace of Nijmegen (now in Belgium and France)

- the Lordship of Mechelen[note 1]

- the Tournaisis

- the Prince-Bishopric of Cambrai, not part of the Seventeen Provinces, incorporated by King Philip II in 1559, ceded to France by the 1678 Peace of Nijmegen (now France: roughly the département Nord and the northern half of Pas-de-Calais)

See also

Notes

- A seignory comes closest to the concept of a heerlijkheid; there is no equivalent in English for the Dutch-language term. In its earliest history, Mechelen was a heerlijkheid of the Bishopric (later Prince-Bishopric) of Liège that exercised its rights through the Chapter of Saint Rumbold though at the same time the Lords of Berthout and later the Dukes of Brabant also exercised or claimed separate feudal rights.

References

- Demographics of the Netherlands, Jan Lahmeyer. Retrieved on 20 February 2014.

- “The States General.” Staten Generaal, www.staten-generaal.nl/begrip/the_states_general.

- Koenigsberger, H. G. (2001). Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521803304.

- Bromley, J.S. (editor) 1970, The New Cambridge Modern History Volume 6: The Rise of Great Britain and Russia, 1688-1715/25, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521075244 (p. 428)