History of Somaliland

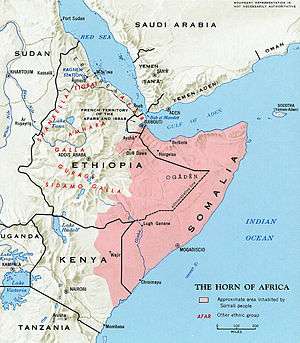

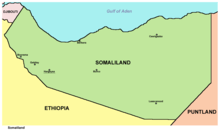

The history of Somaliland, a region of the eastern horn of Africa bordered by the Pacific Ocean, Gulf of Aden, and the east African land mass, begins with human habitation tens of thousands of years ago. It includes the civilizations of Punt, the Ottomans, and colonial influences from Europe and the Middle East.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Somaliland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prehistory

Somaliland has been inhabited since at least the Paleolithic. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished.[1] The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BC.[2] The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artefacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.[3]

According to linguists, the first Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic period from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[4] or the Near East.[5] Other scholars propose that the Afro-Asiatic family developed in situ in the Horn, with its speakers subsequently dispersing from there.[6]

The Laas Geel complex on the outskirts of Hargeisa in northwestern Somalia dates back around 5,000 years, and has rock art depicting both wild animals and decorated cows.[7] Other cave paintings are found in the northern Dhambalin region, which feature one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is in the distinctive Ethiopian-Arabian style, dated to 1000 to 3000 BCE.[8][9] Additionally, between the towns of Las Khorey and El Ayo in northern Somalia lies Karinhegane, the site of numerous cave paintings of real and mythical animals. Each painting has an inscription below it, which collectively have been estimated to be around 2,500 years old.[10][11]

Antiquity

Land of Punt

Most scholars locate the ancient Land of Punt in the Horn of Africa between present-day Somaliland, Djibouti and Eritrea. This is based in part on the fact that the products of Punt, as depicted on the Queen Hatshepsut murals at Deir el-Bahri, were abundantly found in the region but were less common or sometimes absent in the Arabian peninsula. These products included gold and aromatic resins such as myrrh, and ebony; the wild animals depicted in Punt include giraffes, baboons, hippopotami, and leopards. Says Richard Pankhurst : “[Punt] has been identified with territory on both the Arabian and the Horn of Africa coasts. Consideration of the articles which the Egyptians obtained from Punt, notably gold and ivory, suggests, however, that these were primarily of African origin. ... This leads us to suppose that the term Punt probably applied more to African than Arabian territory.”[12][13][14][15] The inhabitants of Punt procured myrrh, spices, gold, ebony, short-horned cattle, ivory and frankincense which was coveted by the Ancient Egyptians. An Ancient Egyptian expedition sent to Punt by the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut is recorded on the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, during the reign of the Puntite King Parahu and Queen Ati.[16]

Periplus

In the Classical era, the city states of Malao (Berbera) and Mundus ([Xiis/Heis) [See original map] prospered, and were deeply involved in the spice trade, selling myrrh and frankincense to The Romans and Egyptians Somaliland and Puntland became known as hubs for spices mainly cinnamon and the cities grew wealthy from it the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea tells us that the northern Somaliland and Puntland regions of modern-day Somalia were independent and competed with Aksum for trade.[17]

Early Islamic states

With the introduction of Islam in the 7th century in what are now the Afar-inhabited parts of Eritrea and Djibouti, the region began to assume a political character independent of Ethiopia. Three Islamic sultanates were founded in and around the area named Shewa (a Semitic-speaking sultanate in eastern Ethiopia, modern Shewa province and ruled by the Mahzumi dynasty, related to Muslim Amharas and Argobbas), Ifat (another Semitic-speaking[18] sultanate located in eastern Ethiopia in what is now eastern Shewa) and Adal and Mora (Gadabursi Clan, Somali, and Harari vassal sultanate of Ifat by 1288, centered on Dakkar and later Harar, with Zeila as its main port and second city, in eastern Ethiopia and in Somaliland's Awdal region; Mora was located in what is now the southern Afar Region of Ethiopia and was subservient to Adal).

At least by the reign of Emperor Amda Seyon I (r. 1314-1344) (and possibly as early as during the reign of Yekuno Amlak or Yagbe'u Seyon), these regions came under Ethiopian suzerainty. During the two centuries that it was under Ethiopian control, intermittent warfare broke out between Ifat (which the other sultanates were under, excepting Shewa, which had been incorporated into Ethiopia) and Ethiopia. In 1403 or 1415[19] (under Emperor Dawit I or Emperor Yeshaq I, respectively), a revolt of Ifat was put down during which the Walashma ruler, Sa'ad ad-Din II, was captured and executed in Zeila, which was sacked. After the war, the reigning king had his minstrels compose a song praising his victory, which contains the first written record of the word "Somali". Upon the return of Sa'ad ad-Din II's sons a few years later, the dynasty took the new title of "king of Adal," instead of the formerly dominant region, Ifat.

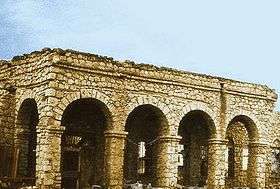

The area remained under Ethiopian control for another century or so. However, starting around 1527 under the charismatic leadership of Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi (Gurey in Somali, Gragn in Amharic, both meaning "left-handed), Adal revolted and invaded medieval Ethiopia. Regrouped Muslim armies with Ottoman support and arms marched into Ethiopia employing scorched earth tactics and slaughtered any Ethiopian that refused to convert from Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity to Islam.[20] Moreover, hundreds of churches were destroyed during the invasion, and an estimated 80% of the manuscripts in the country were destroyed in the process. Adal's use of firearms, still only rarely used in Ethiopia, allowed the conquest of well over half of Ethiopia, reaching as far north as Tigray. The complete conquest of Ethiopia was averted by the timely arrival of a Portuguese expedition led by Cristovão da Gama, son of the famed navigator Vasco da Gama. The Portuguese had been in the area earlier in early 16th centuries (in search of the legendary priest-king Prester John), and although a diplomatic mission from Portugal, led by Rodrigo de Lima, had failed to improve relations between the countries, they responded to the Ethiopian pleas for help and sent a military expedition to their fellow Christians. a Portuguese fleet under the command of Estêvão da Gama was sent from India and arrived at Massawa in February 1541. Here he received an ambassador from the Emperor beseeching him to send help against the Muslims, and in July following a force of 400 musketeers, under the command of Christovão da Gama, younger brother of the admiral, marched into the interior, and being joined by Ethiopian troops they were at first successful against the Somalis but they were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Wofla (28 August 1542), and their commander captured and executed. On February 21, 1543, however, a joint Portuguese-Ethiopian force defeated the Somali-Ottoman army at the Battle of Wayna Daga, in which al-Ghazi was killed and the war won.

Ahmed al-Ghazi's widow married Nur ibn Mujahid in return for his promise to avenge Ahmed's death, who succeeded Imam Ahmad, and continued hostilities against his northern adversaries until he killed the Ethiopian Emperor in his second invasion of Ethiopia, Emir Nur died in 1567. The Portuguese, meanwhile, tried to conquer Mogadishu but according to Duarta Barbosa never succeeded in taking it.[21] The Sultanate of Adal disintegrated into small independent states, many of which were ruled by Somali chiefs.

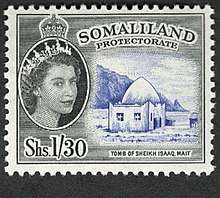

British Somaliland

The British Somaliland protectorate was initially ruled from British India (though later on by the Foreign Office and Colonial Office), and was to play the role of increasing the British Empire's control of the vital Bab-el-Mandeb strait which provided security to the Suez Canal and safety for the Empire's vital naval routes through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

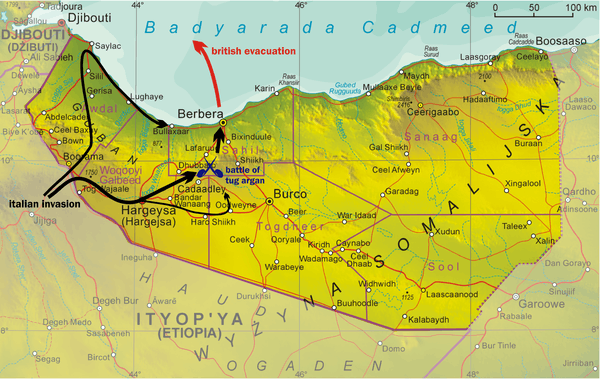

Resentment against the British authorities grew: Britain was seen as excessively profiting from the thriving coastal trading and farming occurring in the territory. Beginning in 1899, religious scholar Mohammed Abdullah Hassan began a campaign to wage a holy war.[22] Hassan raised an army united through the Islamic faith[23] and established the Dervish State, fighting Ethiopian, British, and Italian forces,[24] at first with conventional methods but switching to guerilla tactics after the first clash with the British.[22] The British launched four early expeditions against him, with the last one in 1904 ending in an indecisive British victory.[25] A peace agreement was reached in 1905, and lasted for three years.[22] British forces withdrew to the coast in 1909. In 1912 they raised a camel constabulary to defend the protectorate, but the Dervishes destroyed this in 1914.[25] In the First World War the new Ethiopian Emperor Iyasu V reversed the policy of his predecessor, Menelik II, and aided the Dervishes,[26] supplying them with weapons and financial aid. Germany sent Emil Kirsch, a mechanic, to assist the Dervish Forces as an armourer at Taleh[27] from 1916–1917,[25] and encouraged Ethiopia to aid the Dervishes while promising to recognise any territorial gains made by either of them.[28] The Ottoman Empire sent a letter to Hassan in 1917 assuring him of support and naming him "Emir of the Somali nation".[27] At the height of his power, Hassan led 6000 troops, and by November 1918 the British administration in Somaliland was spending its entire budget trying to stop Dervish activity. The Dervish state fell in February 1920 after a British campaign led by aerial bombing.[25]

Sporadic uprisings were to occur for decades afterwards, however on a much reduced scale with improved British infrastructural spending and a more benign, less paternalistic set of public policy.

During the East African Campaign of WWII, the protectorate was occupied by Italy in August 1940, but recaptured by the British in summer 1941. Some Italian guerrilla fighting (Amedeo Guillet) lasted until 1942.

The conquest of British Somaliland was Italy's only victory (without the cooperation of German troops) in WWII against the Allies.

Separatism

On May 18, 1991, after the collapse of the central government in Somalia in the Somali Civil War, the territory asserted its independence as the self-described Republic of Somaliland. However, the region's self-declared independence remains unrecognized by any country or international organization.[31][32]

References

- Peter Robertshaw (1990). A History of African Archaeology. J. Currey. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-435-08041-9.

- S. A. Brandt (1988). "Early Holocene Mortuary Practices and Hunter-Gatherer Adaptations in Southern Somalia". World Archaeology. 20 (1): 40–56. doi:10.1080/00438243.1988.9980055. JSTOR 124524. PMID 16470993.

- H.W. Seton-Karr (1909). "Prehistoric Implements From Somaliland". 9 (106). Man: 182–183. Retrieved 30 January 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Zarins, Juris (1990), "Early Pastoral Nomadism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia", (Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research)

- Diamond J, Bellwood P (2003) Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions SCIENCE 300, doi:10.1126/science.1078208

- Blench, R. (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman Altamira. pp. 143–144. ISBN 0759104662. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- Bakano, Otto (April 24, 2011). "Grotto galleries show early Somali life". AFP. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Mire, Sada (2008). "The Discovery of Dhambalin Rock Art Site, Somaliland". African Archaeological Review. 25: 153–168. doi:10.1007/s10437-008-9032-2. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- Alberge, Dalya (17 September 2010). "UK archaeologist finds cave paintings at 100 new African sites". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- Hodd, Michael (1994). East African Handbook. Trade & Travel Publications. p. 640. ISBN 0844289833.

- Ali, Ismail Mohamed (1970). Somalia Today: General Information. Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somali Democratic Republic. p. 295.

- Shaw & Nicholson, p.231.

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- Pankhurst, Richard (2001). "The Ethiopians: A history". ISBN 978-0-631-22493-8. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hatshepsut's Temple at Deir El Bahari By Frederick Monderson

- Breasted 1906–07, pp. 246–295, vol. 1.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2009-07-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Pankhurst, Richard. The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th century (Asmara, Eritrea: The Red Sea, Inc., 1997)

- Al-Maqrizi gives the former date, while the Walashma chronicle gives the latter.

- Somalia: From The Dawn of Civilization To The Modern Times: Chapter 8: Somali Hero - Ahmad Gurey (1506-43) Archived 2005-03-09 at the Wayback Machine CivicsWeb

- J. Makong’o & K. Muchanga ;Peak Revision K.C.S.E. History & Government, Page 50

- Abdi Ismail Samatar, The State and Rural Transformation in Northern Somalia, 1884-1986, page 38-39

- Mohamoud, Abdullah A (2006). State collapse and post-conflict development in Africa: the case of Somalia (1960-2001) (illustrated ed.). Purdue University Press. p. 71. ISBN 1557534136.

- Pecastaing, Camille (2011). Jihad in the Arabian sea. Hoover Press. ISBN 0817913769.

- Omissi, David E (1990). Air Power and Colonial Control: The Royal Air Force, 1919–1939. Manchester University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0719029600.

- Foster, Mary LeCron; Rubinstein, Robert A (1986). Peace and war: cross-cultural perspectives. Transaction Publishers. p. 139. ISBN 0887386199.

- Lewis, Ioan M. (2002). A modern history of the Somali: nation and state in the Horn of Africa (illustrated ed.). James Currey. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9780821414958.

With the not-disinterested support of the Turkish and German Consuls in Ethiopia, the new Emperor conceived the aim of creating a vast Muslim Empire in NE Africa. To this end he entered into relations with Sayyid Muhammad, supplying him with financial aid and arms, and arranged for a German mechanic called Emil Kirsch to join the Dervishes and work for them as an armourer at their new headquarters at Taleh where a formidable ring of fortresses had been built by Yemeni masons. Before his pathetically unsuccessful bid for freedom from his exacting masters, Kirsch served the Dervishes well...In 1917, the Italian Administration of Somalia intercepted a document from the Turkish government which assured the Sayyid of support and named him Emir of the Somali nation.

- Shinn, David Hamilton; Ofcansky, Thomas P; Prouty, Chris (2004). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia (illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 405. ISBN 0810849100.

- "Close Residents of Somaliland sit under a war memorial of a MiG fighter jet in the centre of town in Hargeisa". Reuters. 19 May 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Mohamud Omar Ali, Koss Mohammed, Michael Walls. "Peace in Somaliland: An Indigenous Approach to State-Building" (PDF). Academy for Peace and Development. p. 12. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

On 18th May 1991 at this second national meeting, the SNM Central Committee, with the support of a meeting of elders representing the major clans in the Northern Regions, declared the restoration of the Republic of Somaliland, covering the same area as that of the former British Protectorate. The Burao conference also established a government for the Republic

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Lacey, Marc (5 June 2006). "Hargeysa Journal; The Signs Say Somaliland, but the World Says Somalia". The New York Times. p. 4. Archived from the original on 27 June 2011.

- UN in Action: Reforming Somaliland's Judiciary