Battle of Pavia

The Battle of Pavia, fought on the morning of 24 February 1525, was the decisive engagement of the Italian War of 1521–1526 between the Kingdom of France and the Habsburg empire of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor as well as ruler of Spain, Austria, the Low Countries, and the Two Sicilies.

| Battle of Pavia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian War of 1521–1526 | |||||||

Ruprecht Heller, The Battle of Pavia (1529), Nationalmuseum, Stockholm[1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Fewer than 20,000[2] | 20,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,500 killed or wounded[5] | ||||||

The French army was led by King Francis I of France, who laid siege to the city of Pavia (then part of the Duchy of Milan within the Holy Roman Empire) with 26,200 troops since the month of October. The French infantry consisted of 6,000 French soldiers and 17,000 foreigners: 8,000 Swiss mercenaries and 9,000 German-Italian black bands. The French cavalry consisted of 2,000 gendarmes and 1,200 lances fournies. Charles V, intending to break the siege, sent a relief force of 22,300 troops under the command of the Picard Charles de Lannoy, Imperial captain and viceroy of Naples, and of the French renegade Charles III, Duke of Bourbon. The Habsburg infantry consisted of 12,000 German Landsknechte, 5,000 Spaniards, and 3,000 Italians, and its command was exercised by an Italian Condottiero, the Marquis of Pescara, in conjunction with the German military leader Georg Frundsberg and the Spanish captain Antonio de Leyva who was in charge of an Imperial garrison inside Pavia. The cavalry, led by Lannoy and Bourbon, consisted of 1,500 knights and 800 lances.[6]

The battle was fought in the Visconti Park of Mirabello di Pavia, outside the city walls, where Pescara and Frundsberg stationed their forces in pike and shot formation. Francis took a personal initiative and led a cavalry charge against Lannoy, with the possible intent of capturing Bourbon, but it was held by German and Spanish pikemen and pummeled by arquebus fire. The arquebusiers formed a part of the Spanish colunellas and the German doppelsöldner.[7][8][9] A mass of Spanish and German foot soldiers descended on the French cavalry from all sides and initiated to systematically kill the French gendarmes. The remaining French forces, including Swiss mercenaries and Black bands, intervened to protect the King but were surrounded by the pikemen in front of them and by the defensive forces of Pavia that made a sortie behind them.

In the four-hour battle, the French army was split and defeated in detail. Many of the chief nobles of France were killed or captured. In the chaos of the battle, Francis fell from his horse and found himself surrounded by Germans and Spaniards. Two followers of the Duke of Bourbon persuaded Francis to surrender to Charles de Lannoy, who kneeled before the King and made him a prisoner. Francis was imprisoned in the Imperial tower of Pizzighettone, and then transferred to a fortress in Spain where he signed the Treaty of Madrid (1526) with Charles V. By the terms of the treaty, France ceded Burgundy to the Habsburg Netherlands and abandoned the Imperial Duchy of Milan. The outcome of the battle cemented Habsburg ascendancy in Italy and Europe, but Francis denounced it after his liberation and re-opened hostilities over Burgundy and Lombardy shortly after.

Prelude

The French, in possession of Lombardy at the start of the Italian War of 1521–26, had been forced to abandon it after their defeat at the Battle of Bicocca in 1522. Determined to regain it, Francis ordered an invasion of the region in late 1523, under the command of Guillaume Gouffier, Seigneur de Bonnivet; but Bonnivet was defeated by Imperial troops at the Battle of the Sesia and forced to withdraw to France.

Charles de Lannoy now launched an invasion of Provence under the command of Fernando d'Ávalos, and Charles III, Duke of Bourbon (who had recently betrayed Francis and allied himself with the Emperor). While initially successful, the Imperial offensive lost valuable time during the Siege of Marseille and was forced to withdraw back to Italy by the arrival of Francis and the main French army at Avignon.

.png)

In mid-October 1524, Francis himself crossed the Alps and advanced on Milan at the head of an army numbering more than 40,000. Bourbon and Pescara, their troops not yet recovered from the campaign in Provence, were in no position to offer serious resistance.[10] The French army moved in several columns, brushing aside Imperial attempts to hold its advance, but failed to bring the main body of Imperial troops to battle. Nevertheless, Charles de Lannoy, who had concentrated some 16,000 men to resist the 33,000 French troops closing on Milan, decided that the city could not be defended and withdrew to Lodi on 26 October.[11] Having entered Milan and installed Louis II de la Trémoille as the governor, Francis (at the urging of Bonnivet and against the advice of his other senior commanders, who favored a more vigorous pursuit of the retreating Lannoy) advanced on Pavia, where Antonio de Leyva remained with a sizable Imperial garrison of about 9,000.[12]

The main mass of French troops arrived at Pavia in the last days of October. By 2 November, Anne de Montmorency had crossed the Ticino River and invested the city from the south, completing its encirclement. Inside were about 9,000 men, mainly mercenaries whom Antonio de Leyva was able to pay only by melting the church plate.[13] A period of skirmishing and artillery bombardments followed, and several breaches had been made in the walls by mid-November. On 21 November, Francis attempted an assault on the city through two of the breaches, but was beaten back with heavy casualties; hampered by rainy weather and a lack of gunpowder, the French decided to wait for the defenders to starve.[14]

In early December, a Spanish force commanded by Ugo de Moncada landed near Genoa, intending to interfere in a conflict between pro-Valois and pro-Habsburg factions in the city. Francis dispatched a larger force under the Marquis of Saluzzo to intercept them. Confronted by the more numerous French and left without naval support by the arrival of a pro-Valois fleet commanded by Andrea Doria, the Spanish troops surrendered.[15] Francis then signed a secret agreement with Pope Clement VII, who pledged not to assist Charles in exchange for Francis's assistance with the conquest of Naples. Against the advice of his senior commanders, Francis detached a portion of his forces under the Duke of Albany and sent them south to aid the Pope.[16] Lannoy attempted to intercept the expedition near Fiorenzuola, but suffered heavy casualties and was forced to return to Lodi by the intervention of the infamous Black Bands of Giovanni de' Medici, Italian mercenaries which had just entered French service. Medici then returned to Pavia with a supply train of gunpowder and shot gathered by the Duke of Ferrara; but the French position was simultaneously weakened by the departure of nearly 5,000 Grisons Swiss mercenaries, who returned to their cantons in order to defend them against marauding landsknechts.[17]

In January 1525, Lannoy was reinforced by the arrival of Georg Frundsberg with 15,000 fresh landsknechts from Germany and renewed the offensive. Pescara captured the French outpost at Sant'Angelo Lomellina, cutting the lines of communication between Pavia and Milan, while a separate column of landsknechts advanced on Belgiojoso and, despite being briefly pushed back by a raid led by Medici and Bonnivet, occupied the town.[18] By 2 February, Lannoy was only a few miles from Pavia. Francis had encamped the majority of his forces in the great walled park of Mirabello outside the city walls, placing them between Leyva's garrison and the approaching relief army.[19] Skirmishing and sallies by the garrison continued through the month of February. Medici was seriously wounded and withdrew to Piacenza to recuperate, forcing Francis to recall much of the Milan garrison to offset the departure of the Black Band; but the fighting had little overall effect. On 21 February, the Imperial commanders, running low on supplies and mistakenly believing that the French forces were more numerous than their own, decided to launch an attack on Mirabello Castle in order to save face and demoralize the French sufficiently to ensure a safe withdrawal.[20]

Battle

- The times given here are taken from Konstam's reconstruction of the battle.

Movements in the dark

On the evening of 23 February, Lannoy's imperial troops, who had been encamped outside the east wall of the park, began their march north along the walls. Although Konstam indicates that at the same time, the Imperial artillery began a bombardment of the French siege lines—which had become routine during the extended siege—in order to conceal Lannoy's movement,[21] Juan de Oznaya – a soldier who participated in the battle and wrote about it in 1544 – indicates that at that moment, the Imperial troops set their tents on fire to mislead the French into believing that they were retreating.[22] Meanwhile, Imperial engineers quickly worked to create a breach in the park walls, at the Porta Pescarina near the village of San Genesio, through which the Imperial army could enter.[23] By 5:00 am, some 3,000 arquebusiers under the command of Alfonso d'Avalos had entered the park and were rapidly advancing on Mirabello Castle, where they believed the French headquarters to be; simultaneously, Imperial light cavalry spread out from the breach into the park, intending to intercept any French movements.[24]

Meanwhile, a detachment of French cavalry under Charles Tiercelin encountered the Imperial cavalry and began a series of skirmishes with them. A mass of Swiss pikemen under Robert de la Marck, Seigneur de la Flourance moved up to assist them, overrunning a battery of Spanish artillery that had been dragged into the park.[25] They missed De Basto's arcabuceros—who had, by 6:30 am, emerged from the woods near the castle and swiftly overrun it—and blundered into 6,000 of Georg Frundsberg's landsknechts. By 7:00 am, a full-scale infantry battle had developed not far from the original breach.[26]

Francis attacks

A third mass of troops—the German and Spanish heavy cavalry under Lannoy himself, as well as d'Avalos's Spanish infantry—had meanwhile been moving through the woods to the west, closer to where Francis was encamped. The French did not realize the magnitude of the Imperial attack for some time; however, by about 7:20 am, d'Avalos's advance had been spotted by a battery of French artillery, which commenced firing on the Spanish lines. This alerted Francis, who launched a charge against Lannoy's outnumbered cavalry with the entire force of French gendarmes, scattering the Spanish by 7:40 am.[28]

Francis's precipitate advance, however, had not only masked the fire of the French artillery, but also pulled him away from the mass of French infantry, commanded by Richard de la Pole, and by Francois de Lorraine, who led the Black Band of renegade landsknecht pikemen (not to be confused with the Italian mercenary company of arquebusiers by the same name), which was 4,000 to 5,000 men strong. Pescara, left in command of the Spanish forces after Lannoy had followed the retreating cavalry, formed his men up at the edge of the woods and sent messengers to Bourbon, Frundsberg, and De Vasto requesting assistance.[29]

Frundsberg meanwhile mauled the heavily outnumbered Swiss infantry opposing him; Tiercelin and Flourance were unable to hold their troops together, and the French foot began to flee the field.

Endgame

By 8:00 am, a mass of Imperial pikemen and arquebusiers descended on the French cavalry from all sides. Lacking room to maneuver because of the surrounding woods, the French gendarmes were surrounded and systematically killed. Richard de la Pole and Lorraine, advancing to assist Francis, were met by Frundsberg's arriving landsknechts; the French infantry was broken and routed, and de la Pole and Lorraine were both killed. In a particularly bitter contest between Imperial and freelance landsknechts, the Black Band was surrounded by Frundsberg's pikemen and exterminated where it stood. The French king fought on as his horse was killed under him by Cesare Hercolani, an Italian Condottiero;[30][31] surrounded by Spanish arquebusiers and German Landsknecht, he was taken prisoner and escorted from the field.[32][33]

Meanwhile, Antonio de Leyva had sortied with the garrison, overrunning the 3,000 Swiss under Montmorency that had been manning the siege lines. The remnants of the Swiss–both Montmorency's and Flourance's—tried to flee across the river, suffering massive casualties as they did.[34] The French rearguard, under the Duke of Alençon, had taken no part in the battle; when the Duke realized what had occurred in the park, he quickly began to retreat towards Milan. By 9:00 am, the battle was over.

Francis' Capture

The exact nature of Francis's surrender—in particular, who exactly had taken him prisoner—is uncertain, with a variety of candidates put forwards by historians:

- Charles de Lannoy himself, who allegedly kneeled in front of the king and kissed his hand. According to this famous story, Lannoy and Francis I exchanged their swords.

- Three Spanish soldiers: namely Alonso Pita da Veiga, Juan de Urbieta and Diego Dávila.[35]

- Pedro de Valdivia, the future conqueror of Chile.[36]

- A group of Germans that found the King and spared Francis' life at his request.[33]

- The German Nicholas, Count of Salm, who was made a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece for the capture of King Francis.

- The Italian condottiero Cesare Hercolani, who was rewarded as "hero of Pavia" by Charles V.

- In various of these accounts, two followers of Charles de Bourbon persuaded King Francis to surrender.

The fact of the matter was that, as documented in the article for Alonso Pita da Veiga, at the time, no single individual was given credit for the capture of Francis I. The decree granting a coat of arms to Alonso Pita da Veiga for his deeds at the Battle of Pavia, was archived at the General Archive of Simanca (Archivo general de Simancas, legajo 388, rotulado de "Mercedes y Privilegios.') and was issued by Emperor Charles V on 24 July 1529. In that decree, Charles V does not credit a single individual but, rather, a group of individuals that includes da Veiga: " ..... and in the same battle, you (Alonso Pita da Veiga) accomplished so much that you reached the person of said King (Francis I of France) and captured him, jointly with the other persons that captured him." (" .... y en la misma batalla ficistes tanto que allegastes á la misma persona del dicho Rey, y fuistes en prenderle, juntamente con las otras personas que le prendieron ....")

Aftermath

The French defeat was decisive. Aside from Francis, a number of leading French nobles—including Montmorency and Flourance—had been captured; an even greater number—among them Bonnivet, La Tremoille, La Palice, Richard de la Pole, and Lorraine—had been killed in the fighting. Francis was taken to the fortress of Pizzighettone, where he wrote a letter to Louise of Savoy, his mother:

To inform you of how the rest of my ill-fortune is proceeding, all is lost to me save honour and life, which is safe...[37]

Soon afterwards, he finally learned that the Duke of Albany had lost the larger part of his army to attrition and desertion, and had returned to France without ever having reached Naples.[38] The broken remnants of the French forces, aside from a small garrison left to hold the Castel Sforzesco in Milan, retreated across the Alps under the nominal command of Charles IV of Alençon, reaching Lyon by March.[37]

Francis was brought to Genoa, and from there he was taken to Spain by Charles de Lannoy. He remained jailed in a tower in Madrid until the Treaty of Madrid was signed.

Art

In Rome Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici, who acted as Florentine emissary to Charles V in 1535, expressed support for the Emperor's victory by commissioning a rock crystal low relief in the manner of an Antique cameo, from the gem engraver Giovanni Bernardi. The classicizing treatment of the event lent it a timeless, mythic quality and reflected on the culture and taste of the patron.

An oil-on-panel Battle of Pavia, painted by an anonymous Flemish artist, depicts the military engagement between the armies of Charles V and Francis I. Because of its detail, the painting is considered an accurate visual record, probably based on eyewitness accounts.[39] A suite of seven Brussels tapestries after cartoons by Bernard van Orley (left) celebrate the Imperial–Spanish victory.

In 2016, the Spanish writer Arturo Pérez-Reverte published his short story Jodía Pavía (1526)[40] ("Fucking Pavia (1526)"), an enhanced version of a column published in El País Semanal in October 2000. It is a fictional letter by king Francis to his lover, written from his Madrid prison. In it, Francis explains the battle and laments his situation. Pérez-Reverte uses a satirical and colloquial language with frequent anachronism (as an example, there are allusions to Errol Flynn and films).

Notes

- This is the only identified work of the master Ruprecht Heller

- Tucker, Spencer (2011). Battles that Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-59884-429-0.

- Tucker, Spencer (2011). Battles that Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-59884-429-0.

- Tucker, Spencer (2011). Battles that Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-59884-429-0.

- Tucker, Spencer (2011). Battles that Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-59884-429-0.

- Livio Agostini, Piero Pastoretto (1999). Le grandi Battaglie della Storia. Milano: Viviani Editore.

- Tucker 2010, p. 495.

- Brugh, Patrick (2019). Gunpowder, Masculinity, and Warfare in German Texts, 1400–1700. ISBN 9781580469685.

- Morris, T. A. (11 September 2002). Europe and England in the Sixteenth Century. ISBN 9781134748198.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 89.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 30–33.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 34.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 34–35.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 36–39.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 40–41.

- Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 57; Konstam, Pavia 1525, 42–43.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 43–45.

- Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 59; Konstam, Pavia 1525, 46–50.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 50.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 52–53.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 56–57.

- Oznaya. de, Juan (1842). Pidal, Marquis of; Miraflores, Marquis of; Salvá, M. (eds.). Historia de la Guerra de Lombardia, Batalla de Pavía y Prisión del Rey Francisco de Francia. Colección de Documentos Inéditos Para la Historia de España. XXXVIII. Madrid: Imprenta de la viuda de Calero. pp. 289–405.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 56–58. It is unclear whether the breach was in the east wall of the park or the north one; Konstam, based on an analysis of the later course of the battle, suggests that the north is the more likely option.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 58–61.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 62–63.

- Konstam, PavÍa 1525, 63–65.

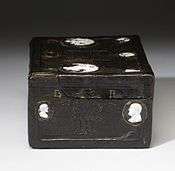

- "Leather Box for the Pennant of Francis I at the Battle of Pavia". The Walters Art Museum.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 65–69.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 69–72.

- Archived 25 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Storia di Pavia

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 72–74.

- Emperor: A new life of Charles V

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 74.

- Juan Carlos Losada, Batallas Decisivas de la Historia de España (Decisive battles of Spanish History), Ed. Punto de lectura, 2004 [Pavía, pg 224]

- Córdoba, J. (2014). "Inés Suárez y la conquista de Chile". Iberoamérica Social: Revista-red de Estudios Sociales (in Spanish). III: 38–42.

- Konstam, Pavia 1525, 76.

- Guicciardini, History of Italy, 348.

- Birmingham Museum of Art : guide to the collection. Birmingham, Ala: Birmingham Museum of Art, 2010.

- (in Spanish) Nueva edición de Jodía Pavía (1525), de Arturo Pérez-Reverte, 4 July 2016, Zenda Libros.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Italian Wars. |

- Black, Jeremy. "Dynasty Forged by Fire." MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 18, no. 3 (Spring 2006): 34–43. ISSN 1040-5992.

- Blockmans, Wim. Emperor Charles V, 1500–1558. Translated by Isola van den Hoven-Vardon. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-340-73110-9.

- Guicciardini, Francesco. The History of Italy. Translated by Sydney Alexander. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-691-00800-0.

- Hall, Bert S. Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe: Gunpowder, Technology, and Tactics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8018-5531-4.

- Knecht, Robert J. Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-57885-X.

- Konstam, Angus. Pavia 1525: The Climax of the Italian Wars. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-85532-504-7.

- Oman, Charles. A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century. London: Methuen & Co., 1937.

- Phillips, Charles and Alan Axelrod. Encyclopedia of Wars. Volume 2. New York: Facts on File, 2005. ISBN 0-8160-2851-6.

- Taylor, Frederick Lewis. The Art of War in Italy, 1494–1529. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1973. ISBN 0-8371-5025-6.

- Tucker, Stephen, ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict:From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. II. ABC-CLIO.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferrer de Couto, Jose, (1862) "Crisol historico español y restauracion de glorias nacionales – Alonso Pita da Veiga en la Batalla de Pavía", pp. 167