Spanish conquest of Yucatán

The Spanish conquest of Yucatán was the campaign undertaken by the Spanish conquistadores against the Late Postclassic Maya states and polities in the Yucatán Peninsula, a vast limestone plain covering south-eastern Mexico, northern Guatemala, and all of Belize. The Spanish conquest of the Yucatán Peninsula was hindered by its politically fragmented state. The Spanish engaged in a strategy of concentrating native populations in newly founded colonial towns. Native resistance to the new nucleated settlements took the form of the flight into inaccessible regions such as the forest or joining neighbouring Maya groups that had not yet submitted to the Spanish. Among the Maya, ambush was a favoured tactic. Spanish weaponry included broadswords, rapiers, lances, pikes, halberds, crossbows, matchlocks and light artillery. Maya warriors fought with flint-tipped spears, bows and arrows and stones, and wore padded cotton armour to protect themselves. The Spanish introduced a number of Old World diseases previously unknown in the Americas, initiating devastating plagues that swept through the native populations.

The first encounter with the Yucatec Maya may have occurred in 1502, when the fourth voyage of Christopher Columbus came across a large trading canoe off Honduras. In 1511, Spanish survivors of the shipwrecked caravel called Santa María de la Barca sought refuge among native groups along the eastern coast of the peninsula. Hernán Cortés made contact with two survivors, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, six years later. In 1517, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba made landfall on the tip of the peninsula. His expedition continued along the coast and suffered heavy losses in a pitched battle at Champotón, forcing a retreat to Cuba. Juan de Grijalva explored the coast in 1518, and heard tales of the wealthy Aztec Empire further west. As a result of these rumours, Hernán Cortés set sail with another fleet. From Cozumel he continued around the peninsula to Tabasco where he fought a battle at Potonchán; from there Cortés continued onward to conquer the Aztec Empire. In 1524, Cortés led a sizeable expedition to Honduras, cutting across southern Campeche, and through Petén in what is now northern Guatemala. In 1527 Francisco de Montejo set sail from Spain with a small fleet. He left garrisons on the east coast, and subjugated the northeast of the peninsula. Montejo then returned to the east to find his garrisons had almost been eliminated; he used a supply ship to explore southwards before looping back around the entire peninsula to central Mexico. Montejo pacified Tabasco with the aid of his son, also named Francisco de Montejo.

In 1531 the Spanish moved their base of operations to Campeche, where they repulsed a significant Maya attack. After this battle, the Spanish founded a town at Chichen Itza in the north. Montejo carved up the province amongst his soldiers. In mid-1533 the local Maya rebelled and laid siege to the small Spanish garrison, which was forced to flee. Towards the end of 1534, or the beginning of 1535, the Spanish retreated from Campeche to Veracruz. In 1535, peaceful attempts by the Franciscan Order to incorporate Yucatán into the Spanish Empire failed after a renewed Spanish military presence at Champotón forced the friars out. Champotón was by now the last Spanish outpost in Yucatán, isolated among a hostile population. In 1541–42 the first permanent Spanish town councils in the entire peninsula were founded at Campeche and Mérida. When the powerful lord of Mani converted to the Roman Catholic religion, his submission to Spain and conversion to Christianity encouraged the lords of the western provinces to accept Spanish rule. In late 1546 an alliance of eastern provinces launched an unsuccessful uprising against the Spanish. The eastern Maya were defeated in a single battle, which marked the final conquest of the northern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula.

The polities of Petén in the south remained independent and received many refugees fleeing from Spanish jurisdiction. In 1618 and in 1619 two unsuccessful Franciscan missions attempted the peaceful conversion of the still pagan Itza. In 1622 the Itza slaughtered two Spanish parties trying to reach their capital Nojpetén. These events ended all Spanish attempts to contact the Itza until 1695. Over the course of 1695 and 1696 a number of Spanish expeditions attempted to reach Nojpetén from the mutually independent Spanish colonies in Yucatán and Guatemala. In early 1695 the Spanish began to build a road from Campeche south towards Petén and activity intensified, sometimes with significant losses on the part of the Spanish. Martín de Urzúa y Arizmendi, governor of Yucatán, launched an assault upon Nojpetén in March 1697; the city fell after a brief battle. With the defeat of the Itza, the last independent and unconquered native kingdom in the Americas fell to the Spanish.

Geography

The Yucatán Peninsula is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the east and by the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west. It can be delimited by a line running from the Laguna de Términos on the Gulf coast through to the Gulf of Honduras on the Caribbean coast. It incorporates the modern Mexican states of Yucatán, Quintana Roo and Campeche, the eastern portion of the state of Tabasco, most of the Guatemalan department of Petén, and all of Belize.[1] Most of the peninsula is formed by a vast plain with few hills or mountains and a generally low coastline. A 15-kilometre (9.3 mi) stretch of high, rocky coast runs south from the city of Campeche on the Gulf Coast. A number of bays are situated along the east coast of the peninsula, from north to south they are Ascensión Bay, Espíritu Santo Bay, Chetumal Bay and Amatique Bay.[2] The north coast features a wide, sandy littoral zone.[2] The extreme north of the peninsula, roughly corresponding to Yucatán State, has underlying bedrock consisting of flat Cenozoic limestone. To the south of this the limestone rises to form the low chain of Puuc Hills, with a steep initial scarp running 160 kilometres (99 mi) east from the Gulf coast near Champotón, terminating some 50 kilometres (31 mi) from the Caribbean coast near the border of Quintana Roo.[3] The hills reach a maximum altitude of 170 metres (560 ft).[2]

The northwestern and northern portions of the Yucatán Peninsula experience lower rainfall than the rest of the peninsula; these regions feature highly porous limestone bedrock resulting in less surface water.[4] This limestone geology results in most rainwater filtering directly through the bedrock to the phreatic zone, from whence it slowly flows to the coasts to form large submarine springs. Various freshwater springs rise along the coast to form watering holes. The filtering of rainwater through the limestone has caused the formation of extensive cave systems. These cave rooves are subject to collapse forming deep sinkholes; if the bottom of the cave is deeper than the groundwater level then a cenote is formed.[5]

In contrast, the northeastern portion of the peninsula is characterised by forested swamplands.[4] The northern portion of the peninsula lacks rivers, except for the Champotón River – all other rivers are located in the south.[2] The Sibun River flows from west to east from south central Quintana Roo to Lake Bacalar on the Caribbean Coast; the Río Hondo flows northwards from Belize to empty into the same lake.[6] Bacalar Lake empties into Chetumal Bay. The Río Nuevo flows from Lamanai Lake in Belize northwards to Chetumal Bay. The Mopan River and the Macal River flow through Belize and join to form the Belize River, which empties into the Caribbean Sea. In the southwest of the peninsula, the San Pedro River, the Candelaría River and the Mamantel River, which all form a part of the Gulf of Mexico drainage.[5]

The Petén region consists of densely forested low-lying limestone plain featuring karstic topography.[7] The area is crossed by low east–west oriented ridges of Cenozoic limestone and is characterised by a variety of forest and soil types; water sources include generally small rivers and low-lying seasonal swamps known as bajos. A chain of fourteen lakes runs across the central drainage basin of Petén; during the rainy season some of these lakes become interconnected. This drainage area measures approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) east–west by 30 kilometres (19 mi) north–south.[9] The largest lake is Lake Petén Itza, near the centre of the drainage basin; it measures 32 by 5 kilometres (19.9 by 3.1 mi). A broad savannah extends south of the central lakes. To the north of the lakes region bajos become more frequent, interspersed with forest. In the far north of Petén the Mirador Basin forms another interior drainage region. To the south the plain gradually rises towards the Guatemalan Highlands.[11] The canopy height of the forest gradually decreases from Petén northwards, averaging from 25 to 35 metres (82 to 115 ft).[12] This dense forest covers northern Petén and Belize, most of Quinatana Roo, southern Campeche and a portion of the south of Yucatán State. Further north, the vegetation turns to lower forest consisting of dense scrub.[13]

Climate

The climate becomes progressively drier towards the north of the peninsula.[13] In the north, the annual mean temperature is 27 °C (81 °F) in Mérida. Average temperature in the peninsula varies from 24 °C (75 °F) in January to 29 °C (84 °F) in July. The lowest temperature on record is 6 °C (43 °F). For the peninsula as a whole, the mean annual precipitation is 1,100 millimetres (43 in). The rainy season lasts from June to September, while the dry season runs from October to May. During the dry season, rainfall averages 300 millimetres (12 in); in the wet season this increases to an average 800 to 900 millimetres (31 to 35 in). The prevailing winds are easterly and have created an east-west precipitation gradient with average rainfall in the east exceeding 1,400 millimetres (55 in) and the north and northwestern portions of the peninsula receiving a maximum of 800 millimetres (31 in). The southeastern portion of the peninsula has a tropical rainy climate with a short dry season in winter.[14]

Petén has a hot climate and receives the highest rainfall in all Mesoamerica.[12] The climate is divided into wet and dry seasons, with the rainy season lasting from June to December,[15] although these seasons are not clearly defined in the south;[16] with rain occurring through most of the year.[12] The climate of Petén varies from tropical in the south to semitropical in the north; temperature varies between 12 and 40 °C (54 and 104 °F), although it does not usually drop beneath 18 °C (64 °F).[15] Mean temperature varies from 24.3 °C (75.7 °F) in the southeast to 26.9 °C (80.4 °F) in the northeast. Highest temperatures are reached from April to June, while January is the coldest month; all Petén experiences a hot dry period in late August. Annual precipitation is high, varying from a mean of 1,198 millimetres (47.2 in) in the northeast to 2,007 millimetres (79.0 in) in central Petén.[16]

Yucatán before the conquest

The first large Maya cities developed in the Petén Basin in the far south of the Yucatán Peninsula as far back as the Middle Preclassic (c. 600–350 BC),[17] and Petén formed the heartland of the ancient Maya civilization during the Classic period (c. AD 250–900).[18] The 16th century Maya provinces of northern Yucatán are likely to have evolved out of polities of the Maya Classic period. From the mid-13th century AD through to the mid-15th century, the League of Mayapán united several of the northern provinces; for a time they shared a joint form of government.[19] The great cities that dominated Petén had fallen into ruin by the beginning of the 10th century AD with the onset of the Classic Maya collapse.[20] A significant Maya presence remained in Petén into the Postclassic period after the abandonment of the major Classic period cities; the population was particularly concentrated near permanent water sources.[21]

In the early 16th century, when the Spanish discovered the Yucatán Peninsula, the region was still dominated by the Maya civilization. It was divided into a number of independent provinces referred to as kuchkabal (plural kuchkabaloob) in the Yucatec Maya language. The various provinces shared a common culture but the internal sociopolitical organisation varied from one province to the next, as did access to important resources. These differences in political and economic makeup often led to hostilities between the provinces. The politically fragmented state of the Yucatán Peninsula at the time of conquest hindered the Spanish invasion, since there was no central political authority to be overthrown. However, the Spanish were also able to exploit this fragmentation by taking advantage of pre-existing rivalries between polities. Estimates of the number of kuchkabal in the northern Yucatán vary from sixteen to twenty-four.[19] The boundaries between polities were not stable, being subject to the effects of alliances and wars; those kuchkabaloob with more centralised forms of government were likely to have had more stable boundaries than those of loose confederations of provinces.[22] When the Spanish discovered Yucatán, the provinces of Mani and Sotuta were two of the most important polities in the region. They were mutually hostile; the Xiu Maya of Mani allied themselves with the Spanish, while the Cocom Maya of Sotuta became the implacable enemies of the European colonisers.[23]

At the time of conquest, polities in the north included Mani, Cehpech and Chakan.[19] Chakan was largely landlocked with a small stretch of coast on the north of the peninsula. Cehpech was a coastal province to its east; further east along the north coast were Ah Kin Chel, Cupul, and Chikinchel.[24] The modern city of Valladolid is situated upon the site of the former capital of Cupul.[25] Cupul and Chinkinchel are known to have been mutually hostile, and to have engaged in wars to control the salt beds of the north coast.[26] Tases was a small landlocked province south of Chikinchel. Ecab was a large province in the east. Uaymil was in the southeast, and Chetumal was to the south of it; all three bordered on the Caribbean Sea. Cochuah was also in the eastern half of the peninsula; it was southwest of Ecab and northwest of Uaymil. Its borders are poorly understood and it may have been landlocked, or have extended to occupy a portion of the Caribbean coast between the latter two kuchkabaloob. The capital of Cochuah was Tihosuco. Hocaba and Sotuta were landlocked provinces north of Mani and southwest of Ah Kin Chel and Cupul. Ah Canul was the northernmost province on the Gulf coast of the peninsula. Canpech (modern Campeche) was to the south of it, followed by Chanputun (modern Champotón). South of Chanputun, and extending west along the Gulf coast was Acalan.[24] This Chontal Maya-speaking province extended east of the Usumacinta River in Tabasco, as far as what is now the southern portion of Campeche state, where their capital was located.[28] In the southern portion of the peninsula, a number of polities occupied the Petén Basin.[17] The Kejache occupied a territory to the north of the Itza and east of Acalan, between the Petén lakes and what is now Campeche,[28] and to the west of Chetumal.[24] The Cholan Maya-speaking Lakandon (not to be confused with the modern inhabitants of Chiapas by that name) controlled territory along the tributaries of the Usumacinta River spanning southwestern Petén in Guatemala and eastern Chiapas.[28] The Lakandon had a fierce reputation amongst the Spanish.[29]

Although there is insufficient data to accurately estimate population sizes at the time of contact with the Spanish, early Spanish reports suggest that sizeable Maya populations existed in Petén, particularly around the central lakes and along the rivers.[30] Before their defeat in 1697 the Itza controlled or influenced much of Petén and parts of Belize. The Itza were warlike, and their martial prowess impressed both neighbouring Maya kingdoms and their Spanish enemies. Their capital was Nojpetén, an island city upon Lake Petén Itzá; it has developed into the modern town of Flores, which is the capital of the Petén department of Guatemala.[28] The Itza spoke a variety of Yucatecan Maya.[31] The Kowoj were the second in importance; they were hostile towards their Itza neighbours. The Kowoj were located to the east of the Itza, around the eastern Petén lakes: Lake Salpetén, Lake Macanché, Lake Yaxhá and Lake Sacnab.[32] The Yalain appear to have been one of the three dominant polities in Postclassic central Petén, alongside the Itza and the Kowoj. The Yalain territory had its maximum extension from the east shore of Lake Petén Itzá eastwards to Tipuj in Belize.[33] In the 17th century the Yalain capital was located at the site of that name on the north shore of Lake Macanché. At the time of Spanish contact the Yalain were allied with the Itza, an alliance cemented by intermarriage between the elites of both groups.[33] In the late 17th century, Spanish colonial records document hostilities between Maya groups in the lakes region, with the incursion of the Kowoj into former Yalain sites including Zacpeten on Lake Macanché and Ixlu on Lake Salpetén.[35] Other groups in Petén are less well known, and their precise territorial extent and political makeup remains obscure; among them were the Chinamita, the Icaiche, the Kejache, the Lakandon Chʼol, the Manche Chʼol, and the Mopan.[36]

Impact of Old World diseases

A single soldier arriving in Mexico in 1520 was carrying smallpox and thus initiated the devastating plagues that swept through the native populations of the Americas.[37] The European diseases that ravaged the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas also severely affected the various Maya groups of the entire Yucatán Peninsula. Modern estimates of native population decline vary from 75% to 90% mortality. The terrible plagues that swept the peninsula were recorded in Yucatec Maya written histories, which combined with those of neighbouring Maya peoples in the Guatemalan Highlands, suggest that smallpox was rapidly transmitted throughout the Maya area the same year that it arrived in central Mexico with the forces under the command of Pánfilo Narváez. Old World diseases are often mentioned only briefly in indigenous accounts, making it difficult to identify the exact culprit. Among the most deadly were the aforementioned smallpox, influenza, measles and a number of pulmonary diseases, including tuberculosis; the latter disease was attributed to the arrival of the Spanish by the Maya inhabitants of Yucatán.[38]

These diseases swept through Yucatán in the 1520s and 1530s, with periodic recurrences throughout the 16th century. By the late 16th century, the reports of high fevers suggest the arrival of malaria in the region, and yellow fever was first reported in the mid-17th century, with a terse mention in the Chilam Balam of Chumayel for 1648. That particular outbreak was traced back to the island of Guadaloupe in the Caribbean, from whence it was introduced to the port city of Campeche, and from there was transmitted to Mérida. Mortality was high, with approximately 50% of the population of some Yucatec Maya settlements being wiped out. Sixteen Franciscan friars are reported to have died in Mérida, probably the majority of the Franciscans based there at the time, and who had probably numbered not much more than twenty before the outbreak.[38] Those areas of the peninsula that experience damper conditions, particularly those possessing swamplands, became rapidly depopulated after the conquest with the introduction of malaria and other waterborne parasites. An example was the one-time well-populated province of Ecab occupying the northeastern portion of the peninsula. In 1528, when Francisco de Montejo occupied the town of Conil for two months, the Spanish recorded approximately 5,000 houses in the town; the adult male population at the time has been conservatively estimated as 3,000. By 1549, Spanish records show that only 80 tributaries were registered to be taxed, indicating a population drop in Conil of more than 90% in 21 years.[4] The native population of the northeastern portion of the peninsula was almost completely eliminated within fifty years of the conquest.[39]

In the south, conditions conducive to the spread of malaria existed throughout Petén and Belize.[39] At the time of the fall of Nojpetén in 1697, there are estimated to have been 60,000 Maya living around Lake Petén Itzá, including a large number of refugees from other areas. It is estimated that 88% of them died during the first ten years of colonial rule owing to a combination of disease and war.[40] Likewise, in Tabasco the population of approximately 30,000 was reduced by an estimated 90%, with measles, smallpox, catarrhs, dysentery and fevers being the main culprits.[39]

Weaponry, strategies and tactics

The Spanish engaged in a strategy of concentrating native populations in newly founded colonial towns, or reducciones (also known as congregaciones).[41] Native resistance to the new nucleated settlements took the form of the flight of the indigenous inhabitants into inaccessible regions such as the forest or joining neighbouring Maya groups that had not yet submitted to the Spanish.[42] Those that remained behind in the reducciones often fell victim to contagious diseases.[43] An example of the effect on populations of this strategy is the province of Acalan, which occupied an area spanning southern Campeche and eastern Tabasco. When Hernán Cortés passed through Acalan in 1525 he estimated the population size as at least 10,000. In 1553 the population was recorded at around 4,000. In 1557 the population was forcibly moved to Tixchel on the Gulf coast, so as to be more easily accessible to the Spanish authorities. In 1561 the Spanish recorded only 250 tribute-paying inhabitants of Tixchel, which probably had a total population of about 1,100. This indicates a 90% drop in population over a 36-year span. Some of the inhabitants had fled Tixchel for the forest, while others had succumbed to disease, malnutrition and inadequate housing in the Spanish reducción. Coastal reducciones, while convenient for Spanish administration, were vulnerable to pirate attacks; in the case of Tixchel, pirate attacks and contagious European diseases led to the eradication of the reducción town and the extinction of the Chontal Maya of Campeche.[39] Among the Maya, ambush was a favoured tactic.[44]

Spanish weaponry and armour

The 16th-century Spanish conquistadors were armed with broadswords, rapiers, crossbows, matchlocks and light artillery. Mounted conquistadors were armed with a 3.7-metre (12 ft) lance, that also served as a pike for infantrymen. A variety of halberds and bills were also employed. As well as the one-handed broadsword, a 1.7-metre (5.5 ft) long two-handed version was also used. Crossbows had 0.61-metre (2 ft) arms stiffened with hardwoods, horn, bone and cane, and supplied with a stirrup to facilitate drawing the string with a crank and pulley. Crossbows were easier to maintain than matchlocks, especially in the humid tropical climate of the Caribbean region that included much of the Yucatán Peninsula.[45]

Native weaponry and armour

Maya warriors entered battle against the Spanish with flint-tipped spears, bows and arrows and stones. They wore padded cotton armour to protect themselves.[44] Members of the Maya aristocracy wore quilted cotton armour, and some warriors of lesser rank wore twisted rolls of cotton wrapped around their bodies. Warriors bore wooden or animal hide shields decorated with feathers and animal skins.[46]

First encounters: 1502 and 1511

On 30 July 1502, during his fourth voyage, Christopher Columbus arrived at Guanaja, one of the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras. He sent his brother Bartholomew to scout the island. As Bartholomew explored the island with two boats, a large canoe approached from the west, apparently en route to the island. The canoe was carved from one large tree trunk and was powered by twenty-five naked rowers.[47] Curious as to the visitors, Bartholomew Columbus seized and boarded it. He found it was a Maya trading canoe from Yucatán, carrying well-dressed Maya and a rich cargo that included ceramics, cotton textiles, yellow stone axes, flint-studded war clubs, copper axes and bells, and cacao.[48] Also among the cargo were a small number of women and children, probably destined to be sold as slaves, as were a number of the rowers. The Europeans looted whatever took their interest from amongst the cargo and seized the elderly Maya captain to serve as an interpreter; the canoe was then allowed to continue on its way.[49] This was the first recorded contact between Europeans and the Maya.[50] It is likely that news of the piratical strangers in the Caribbean passed along the Maya trade routes – the first prophecies of bearded invaders sent by Kukulkan, the northern Maya feathered serpent god, were probably recorded around this time, and in due course passed into the books of Chilam Balam.[51]

In 1511 the Spanish caravel Santa María de la Barca set sail along the Central American coast under the command of Pedro de Valdivia.[52] The ship was sailing to Santo Domingo from Darién to inform the colonial authorities there of ongoing conflict between conquistadors Diego de Nicuesa and Vasco Nuñez de Balboa in Darién.[53] The ship foundered upon a reef known as Las Víboras ("The Vipers") or, alternatively, Los Alacranes ("The Scorpions"), somewhere off Jamaica.[52] There were just twenty survivors from the wreck, including Captain Valdivia, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero.[54] They set themselves adrift in one of the ship's boats, with bad oars and no sail; after thirteen days during which half of the survivors died, they made landfall upon the coast of Yucatán.[52] There they were seized by Halach Uinik, a Maya lord. Captain Vildivia was sacrificed with four of his companions, and their flesh was served at a feast. Aguilar and Guerrero were held prisoner and fattened for killing, together with five or six of their shipmates. Aguilar and Guerrero managed to escape their captors and fled to a neighbouring lord who was an enemy of Halach Uinik; he took them prisoner and kept them as slaves. After a time, Gonzalo Guerrero was passed as a slave to the lord Nachan Can of Chetumal. Guerrero became completely Mayanised and served his new lord with such loyalty that he was married to one of Nachan Chan's daughters, Zazil Ha, by whom he had three children. By 1514, Guerrero had achieved the rank of nacom, a war leader who served against Nachan Chan's enemies.[55]

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, 1517

In 1517, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba set sail from Cuba with a small fleet,[56] consisting of two caravels and a brigantine,[57] with the dual intention of exploration and of rounding up slaves.[56] The experienced Antón de Alaminos served as pilot; he had previously served as pilot under Christopher Columbus on his final voyage. Also among the approximately 100-strong expedition members was Bernal Díaz del Castillo.[58] The expedition sailed west from Cuba for three weeks, and weathered a two-day storm a week before sighting the coast of the northeastern tip of the Yucatán Peninsula. The ships could not put in close to the shore due to the shallowness of the coastal waters. However, they could see a Maya city some two leagues inland, upon a low hill. The Spanish called it Gran Cairo (literally "Great Cairo") due to its size and its pyramids.[57] Although the location is not now known with certainty, it is believed that this first sighting of Yucatán was at Isla Mujeres.

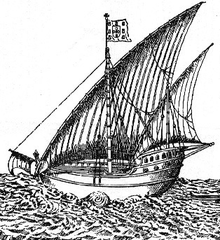

The following morning, the Spanish sent the two ships with a shallower draught to find a safe approach through the shallows.[57] The caravels anchored about one league from the shore.[44] Ten large canoes powered by both sails and oars rowed out to meet the Spanish ships. Over thirty Maya boarded the vessels and mixed freely with the Spaniards. The Maya visitors accepted gifts of beads, and the leader indicated with signs that they would return to take the Spanish ashore the following day.[57]

The Maya leader returned the following day with twelve canoes, as promised. The Spanish could see from afar that the shore was packed with natives. The conquistadors put ashore in the brigantine and the ships' boats; a few of the more daring Spaniards boarded the native canoes. The Spanish named the headland Cape Catoche, after some words spoken by the Maya leader, which sounded to the Spanish like cones catoche. Once ashore, the Spaniards clustered loosely together and advanced towards the city along a path among low, scrub-covered hillocks. At this point the Maya leader gave a shout and the Spanish party was ambushed by Maya warriors armed with spears, bows and arrows, and stones. Thirteen Spaniards were injured by arrows in the first assault, but the conquistadors regrouped and repulsed the Maya attack. They advanced to a small plaza bordered by temples upon the outskirts of the city.[44] When the Spaniards ransacked the temples they found a number of low-grade gold items, which filled them with enthusiasm. The expedition captured two Mayas to be used as interpreters and retreated to the ships. Over the following days the Spanish discovered that although the Maya arrows had struck with little force, the flint arrowheads tended to shatter on impact, causing infected wounds and a slow death; two of the wounded Spaniards died from the arrow-wounds inflicted in the ambush.[60]

Over the next fifteen days the fleet slowly followed the coastline west, and then south.[60] The casks brought from Cuba were leaking and the expedition was now running dangerously low on fresh water; the hunt for more became an overriding priority as the expedition advanced, and shore parties searching for water were left dangerously exposed because the ships could not pull close to the shore due to the shallows.[61] On 23 February 1517, the day of Saint Lazarus, another city was spotted and named San Lázaro by the Spanish – it is now known by its original Maya name, Campeche. A large contingent put ashore in the brigantine and the ships' boats to fill their water casks in a freshwater pool. They were approached by about fifty finely dressed and unarmed Indians while the water was being loaded into the boats; they questioned the Spaniards as to their purpose by means of signs. The Spanish party then accepted an invitation to enter the city.[62] They were led amongst large buildings until they stood before a blood-caked altar, where many of the city's inhabitants crowded around. The Indians piled reeds before the visitors; this act was followed by a procession of armed Maya warriors in full war paint, followed by ten Maya priests. The Maya set fire to the reeds and indicated that the Spanish would be killed if they were not gone by the time the reeds had been consumed. The Spanish party withdrew in defensive formation to the shore and rapidly boarded their boats to retreat to the safety of the ships.[63]

The small fleet continued for six more days in fine weather, followed by four stormy days.[64] By this time water was once again dangerously short.[65] The ships spotted an inlet close to another city,[66] Champotón, and a landing party discovered fresh water. Armed Maya warriors approached from the city while the water casks were being filled. Communication was once again attempted with signs. Night fell by the time the water casks had been filled and the attempts at communication concluded. In the darkness the Spaniards could hear the movements of large numbers of Maya warriors. They decided that a night-time retreat would be too risky; instead, they posted guards and waited for dawn. At sunrise, the Spanish saw that they had been surrounded by a sizeable army. The massed Maya warriors launched an assault with missiles, including arrows, darts and stones; they then charged into hand-to-hand combat with spears and clubs. Eighty of the defenders were wounded in the initial barrage of missiles, and two Spaniards were captured in the frantic mêlée that followed. All of the Spanish party received wounds, including Hernández de Córdoba. The Spanish regrouped in a defensive formation and forced passage to the shore, where their discipline collapsed and a frantic scramble for the boats ensued, leaving the Spanish vulnerable to the pursuing Maya warriors who waded into the sea behind them.[66] Most of the precious water casks were abandoned on the beach.[67] When the surviving Spanish reached the safety of the ships, they realised that they had lost over fifty men, more than half their number.[66] Five men died from their wounds in the following days.[68] The battle had lasted only an hour,[67] and the Spanish named the locale as the Coast of the Disastrous Battle. They were now far from help and low on supplies; too many men had been lost and injured to sail all three ships back to Cuba. They decided to abandon their smallest ship, the brigantine, although it was purchased on credit from Governor Velásquez of Cuba.[67]

The few men who had not been wounded because they were manning the ships during the battle were reinforced with three men who had suffered relatively minor wounds; they put ashore at a remote beach to dig for water. They found some and brought it back to the ships, although it sickened those who drank it.[69] The two ships sailed through a storm for two days and nights; Alaminos, the pilot, then steered a course for Florida, where they found good drinking water, although they lost one man to the local Indians and another drank so much water that he died. The ships finally made port in Cuba, where Hernández de Cordóba wrote a report to Governor Velázquez describing the voyage, the cities, the plantations, and, most importantly, the discovery of gold. Hernández died soon after from his wounds.[70] The two captured Maya survived the voyage to Cuba and were interrogated; they swore that there was abundant gold in Yucatán.[71]

Based upon Hernández de Córdoba's report and the testimony of the interrogated Indian prisoners, Governor Velázquez wrote to the Council of the Indies notifying it of "his" discovery.[71]

Juan de Grijalva, 1518

Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba, was enthused by Hernández de Córdoba's report of gold in Yucatán. He organised a new expedition consisting of four ships and 260 men.[72] He placed his nephew Juan de Grijalva in command. Francisco de Montejo, who would eventually conquer much of the peninsula, was captain of one of the ships;[73] Pedro de Alvarado and Alonso d'Avila captained the other ships.[74] Bernal Díaz del Castillo served on the crew; he was able to secure a place on the expedition as a favour from the governor, who was his kinsman.[75] Antón de Alaminos once again served as pilot. Governor Velázquez provided all four ships, in an attempt to protect his claim over the peninsula.[71] The small fleet was stocked with crossbows, muskets, barter goods, salted pork and cassava bread.[77] Grijalva also took one of the captured Indians from the Hernández expedition.[75]

The fleet left Cuba in April 1518, and made its first landfall upon the island of Cozumel,[75] off the east coast of Yucatán. The Maya inhabitants of Cozumel fled the Spanish and would not respond to Grijalva's friendly overtures. The fleet sailed south from Cozumel, along the east coast of the peninsula. The Spanish spotted three large Maya cities along the coast, one of which was probably Tulum. On Ascension Thursday the fleet discovered a large bay, which the Spanish named Bahía de la Ascensión. Grijalva did not land at any of these cities and turned back north from Ascensión Bay. He looped around the north of the Yucatán Peninsula to sail down the west coast. At Campeche the Spanish tried to barter for water but the Maya refused, so Grijalva opened fire against the city with small cannon; the inhabitants fled, allowing the Spanish to take the abandoned city. Messages were sent with a few Maya who had been too slow to escape but the Maya remained hidden in the forest. The Spanish boarded their ships and continued along the coast.[75]

At Champotón, where the inhabitants had routed Hernández and his men, the fleet was approached by a small number of large war canoes, but the ships' cannon soon put them to flight.[75] At the mouth of the Tabasco River the Spanish sighted massed warriors and canoes but the natives did not approach.[79] By means of interpreters, Grijalva indicated that he wished to trade and bartered wine and beads in exchange for food and other supplies. From the natives they received a few gold trinkets and news of the riches of the Aztec Empire to the west. The expedition continued far enough to confirm the reality of the gold-rich empire,[80] sailing as far north as Pánuco River. As the fleet returned to Cuba, the Spanish attacked Champotón to avenge the previous year's defeat of the Spanish expedition led by Hernández. One Spaniard was killed and fifty were wounded in the ensuing battle, including Grijalva. Grijalva put into the port of Havana five months after he had left.

Hernán Cortés, 1519

Grijalva's return aroused great interest in Cuba, and Yucatán was believed to be a land of riches waiting to be plundered. A new expedition was organised, with a fleet of eleven ships carrying 500 men and some horses. Hernán Cortés was placed in command, and his crew included officers that would become famous conquistadors, including Pedro de Alvarado, Cristóbal de Olid, Gonzalo de Sandoval and Diego de Ordaz. Also aboard were Francisco de Montejo and Bernal Díaz del Castillo, veterans of the Grijalva expedition.

The fleet made its first landfall at Cozumel, and Cortés remained there for several days. Maya temples were cast down and a Christian cross was put up on one of them. At Cozumel, Cortés heard rumours of bearded men on the Yucatán mainland, who he presumed were Europeans.[81] Cortés sent out messengers to them and was able to rescue the shipwrecked Gerónimo de Aguilar, who had been enslaved by a Maya lord. Aguilar had learnt the Yucatec Maya language and became Cortés' interpreter.[82]

From Cozumel, the fleet looped around the north of the Yucatán Peninsula and followed the coast to the Tabasco River, which Cortés renamed as the Grijalva River in honour of the Spanish captain who had discovered it. In Tabasco, Cortés anchored his ships at Potonchán,[84] a Chontal Maya town.[85] The Maya prepared for battle but the Spanish horses and firearms quickly decided the outcome.[84] The defeated Chontal Maya lords offered gold, food, clothing and a group of young women in tribute to the victors.[84] Among these women was a young Maya noblewoman called Malintzin,[84] who was given the Spanish name Marina. She spoke Maya and Nahuatl and became the means by which Cortés was able to communicate with the Aztecs. Marina became Cortés' consort and eventually bore him a son.[84] From Tabasco, Cortés continued to Cempoala in Veracruz, a subject city of the Aztec Empire,[84] and from there on to conquer the Aztecs.[86]

In 1519, Cortés sent the veteran Francisco de Montejo back to Spain with treasure for the king. While he was in Spain, Montejo pleaded Cortés' cause against the supporters of Diego de Velásquez. Montejo remained in Spain for seven years, and eventually succeeded in acquiring the hereditary military title of adelantado.

Hernán Cortés in the Maya lowlands, 1524–25

In 1524, after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés led an expedition to Honduras over land, cutting across Acalan in southern Campeche and the Itza kingdom in what is now the northern Petén Department of Guatemala.[88] His aim was to subdue the rebellious Cristóbal de Olid, whom he had sent to conquer Honduras; Olid had, however, set himself up independently on his arrival in that territory. Cortés left Tenochtitlan on 12 October 1524 with 140 Spanish soldiers, 93 of them mounted, 3,000 Mexican warriors, 150 horses, a herd of pigs, artillery, munitions and other supplies. He also had with him the captured Aztec emperor Cuauhtemoc, and Cohuanacox and Tetlepanquetzal, the captive Aztec lords of Texcoco and Tlacopan. Cortés marched into Maya territory in Tabasco; the army crossed the Usumacinta River near Tenosique and crossed into the Chontal Maya province of Acalan, where he recruited 600 Chontal Maya carriers. In Acalan, Cortés believed that the captive Aztec lords were plotting against him and he ordered Cuauhtemoc and Tetlepanquetzal to be hanged. Cortés and his army left Acalan on 5 March 1525.

The expedition passed onwards through Kejache territory and reported that the Kejache towns were situated in easily defensible locations and were often fortified.[89] One of these was built on a rocky outcrop near a lake and a river that fed into it. The town was fortified with a wooden palisade and was surrounded by a moat. Cortés reported that the town of Tiac was even larger and was fortified with walls, watchtowers and earthworks; the town itself was divided into three individually fortified districts. Tiac was said to have been at war with the unnamed smaller town.[90] The Kejache claimed that their towns were fortified against the attacks of their aggressive Itza neighbours.[91]

They arrived at the north shore of Lake Petén Itzá on 13 March 1525. The Roman Catholic priests accompanying the expedition celebrated mass in the presence of Aj Kan Ekʼ, the king of the Itza, who was said to be so impressed that he pledged to worship the cross and to destroy his idols. Cortés accepted an invitation from Kan Ekʼ to visit Nojpetén (also known as Tayasal), and crossed to the Maya city with 20 Spanish soldiers while the rest of his army continued around the lake to meet him on the south shore.[93] On his departure from Nojpetén, Cortés left behind a cross and a lame horse that the Itza treated as a deity, attempting to feed it poultry, meat and flowers, but the animal soon died.[94] The Spanish did not officially contact the Itza again until the arrival of Franciscan priests in 1618, when Cortés' cross was said to still be standing at Nojpetén.[88]

From the lake, Cortés continued south along the western slopes of the Maya Mountains, a particularly arduous journey that took 12 days to cover 32 kilometres (20 mi), during which he lost more than two-thirds of his horses. When he came to a river swollen with the constant torrential rains that had been falling during the expedition, Cortés turned upstream to the Gracias a Dios rapids, which took two days to cross and cost him more horses.

On 15 April 1525 the expedition arrived at the Maya village of Tenciz. With local guides they headed into the hills north of Lake Izabal, where their guides abandoned them to their fate. The expedition became lost in the hills and came close to starvation before they captured a Maya boy who led them to safety. Cortés found a village on the shore of Lake Izabal, perhaps Xocolo. He crossed the Dulce River to the settlement of Nito, somewhere on the Amatique Bay,[95] with about a dozen companions, and waited there for the rest of his army to regroup over the next week. By this time the remnants of the expedition had been reduced to a few hundred; Cortés succeeded in contacting the Spaniards he was searching for, only to find that Cristóbal de Olid's own officers had already put down his rebellion. Cortés then returned to Mexico by sea.[96]

Francisco de Montejo, 1527–28

The richer lands of Mexico engaged the main attention of the conquistadors for some years, then in 1526 Francisco de Montejo (a veteran of the Grijalva and Cortés expeditions) successfully petitioned the King of Spain for the right to conquer Yucatán. On 8 December of that year he was issued with the hereditary military title of adelantado and permission to colonise the Yucatán Peninsula.[97] In 1527, he left Spain with 400 men in four ships, with horses, small arms, cannon and provisions.[98] He set sail for Santo Domingo, where more supplies and horses were collected, allowing Montejo to increase his cavalry to fifty.[100] One of the ships was left at Santo Domingo as a supply ship to provide later support; the other ships set sail and reached Cozumel in the second half of September 1527. Montejo was received in peace by the lord of Cozumel, Aj Naum Pat, but the ships only stopped briefly before making for the Yucatán coast. The expedition made landfall somewhere near Xelha in the Maya province of Ekab, in what is now Mexico's Quintana Roo state.[101]

Montejo garrisoned Xelha with 40 soldiers under his second-in-command, Alonso d'Avila, and posted 20 more at nearby Pole. Xelha was renamed Salamanca de Xelha and became the first Spanish settlement on the peninsula. The provisions were soon exhausted and additional food was seized from the local Maya villagers; this too was soon consumed. Many local Maya fled into the forest and Spanish raiding parties scoured the surrounding area for food, finding little.[102] With discontent growing among his men, Montejo took the drastic step of burning his ships; this strengthened the resolve of his troops, who gradually acclimatised to the harsh conditions of Yucatán.[103] Montejo was able to get more food from the still-friendly Aj Nuam Pat, when the latter made a visit to the mainland.[102] Montejo took 125 men and set out on an expedition to explore the north-eastern portion of the Yucatán peninsula. His expedition passed through the towns of Xamanha, Mochis and Belma, none of which survives today.[nb 1] At Belma, Montejo gathered the leaders of the nearby Maya towns and ordered them to swear loyalty to the Spanish Crown. After this, Montejo led his men to Conil, a town in Ekab that was described as having 5,000 houses, where the Spanish party halted for two months.

In the spring of 1528, Montejo left Conil for the city of Chauaca, which was abandoned by its Maya inhabitants under cover of darkness. The following morning, the inhabitants attacked the Spanish party but were defeated. The Spanish then continued to Ake, some 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) north of Tizimín, where they engaged in a major battle against the Maya, killing more than 1,200 of them. After this Spanish victory, the neighbouring Maya leaders all surrendered. Montejo's party then continued to Sisia and Loche before heading back to Xelha. Montejo arrived at Xelha with only 60 of his party, and found that only 12 of his 40-man garrison survived, while the garrison at Pole had been entirely wiped out.[105]

The support ship eventually arrived from Santo Domingo, and Montejo used it to sail south along the coast, while he sent D'Avila over land. Montejo discovered the thriving port city of Chaktumal (modern Chetumal).[106] At Chaktumal, Montejo learnt that shipwrecked Spanish sailor Gonzalo de Guerrero was in the region, and Montejo sent messages to him, inviting him to return to join his compatriots, but the Mayanised Guerrero declined.

The Maya at Chaktumal fed false information to the Spanish, and Montejo was unable to find d'Avila and link up with him. D'Avila returned overland to Xelha, and transferred the fledgling Spanish colony to nearby Xamanha, modern Playa del Carmen, which Montejo considered to be a better port.[108] After waiting for d'Avila without result, Montejo sailed south as far as the Ulúa River in Honduras before turning around and heading back up the coast to finally meet up with his lieutenant at Xamanha. Late in 1528, Montejo left d'Avila to oversee Xamanha and sailed north to loop around the Yucatán Peninsula and head for the Spanish colony of New Spain in central Mexico.

Francisco de Montejo and Alonso d'Avila, 1531–35

Montejo was appointed alcalde mayor (a local colonial governor) of Tabasco in 1529, and pacified that province with the aid of his son, also named Francisco de Montejo. D'Avila was sent from eastern Yucatán to conquer Acalan, which extended southeast of the Laguna de Terminos. Montejo the Younger founded Salamanca de Xicalango as a base of operations. In 1530 D'Avila established Salamanca de Acalán as a base from which to launch new attempts to conquer Yucatán.[108] Salamanca de Acalán proved a disappointment, with no gold for the taking and with lower levels of population than had been hoped. D'Avila soon abandoned the new settlement and set off across the lands of the Kejache to Champotón, arriving there towards the end of 1530.[109] During a colonial power struggle in Tabasco, the elder Montejo was imprisoned for a time. Upon his release, he met up with his son in Xicalango, Tabasco, and they then both rejoined d'Avila at Champotón.

In 1531 Montejo moved his base of operations to Campeche.[110] Alonso d'Avila was sent overland to Chauaca in the east of the peninsula, passing through Maní where he was well received by the Xiu Maya. D'Avila continued southeast to Chetumal where he founded the Spanish town of Villa Real ("Royal Town"). The local Maya fiercely resisted the placement of the new Spanish colony and d'Avila and his men were forced to abandon Villa Real and make for Honduras in canoes.

At Campeche, the Maya amassed a strong force and attacked the city; the Spanish were able to fight them off, a battle in which the elder Montejo was almost killed.[111] Aj Canul, the lord of the attacking Maya, surrendered to the Spanish. After this battle, the younger Francisco de Montejo was despatched to the northern Cupul province, where the lord Naabon Cupul reluctantly allowed him to found the Spanish town of Ciudad Real at Chichen Itza. Montejo carved up the province amongst his soldiers and gave each of his men two to three thousand Maya in encomienda. After six months of Spanish rule, Cupul dissatisfaction could no longer be contained and Naabon Cupul was killed during a failed attempt to kill Montejo the Younger. The death of their lord only served to inflame Cupul anger and, in mid 1533, they laid siege to the small Spanish garrison at Chichen Itza. Montejo the Younger abandoned Ciudad Real by night after arranging a distraction for their attackers, and he and his men fled west, where the Chel, Pech and Xiu provinces remained obedient to Spanish rule. Montejo the Younger was received in friendship by Namux Chel, the lord of the Chel province, at Dzilam. In the spring of 1534 he rejoined his father in the Chakan province at Dzikabal, near Tʼho (the modern city of Mérida).

While his son had been attempting to consolidate the Spanish control of Cupul, Francisco de Montejo the Elder had met the Xiu ruler at Maní. The Xiu Maya maintained their friendship with the Spanish throughout the conquest and Spanish authority was eventually established over Yucatán in large part due to Xiu support. The Montejos, after reuniting at Dzikabal, founded a new Spanish town at Dzilam, although the Spanish suffered hardships there. Montejo the Elder returned to Campeche, where he was received with friendship by the local Maya. He was accompanied by the friendly Chel lord Namux Chel, who travelled on horseback, and two of the lord's cousins, who were taken in chains.[113] Montejo the Younger remained behind in Dzilam to continue his attempts at conquest of the region but, finding the situation too difficult, he soon retreated to Campeche to rejoin his father and Alonso d'Avila, who had returned to Campeche shortly before Montejo the Younger. Around this time, the news began to arrive of Francisco Pizarro's conquests in Peru and the rich plunder that his soldiers were taking there, undermining the morale of Montejo's already disenchanted band of followers. Montejo's soldiers began to abandon him to seek their fortune elsewhere; in seven years of attempted conquest in the northern provinces of the Yucatán Peninsula, very little gold had been found. Towards the end of 1534 or the beginning of the next year, Montejo the Elder and his son retreated from Campeche to Veracruz, taking their remaining soldiers with them.

Montejo the Elder became embroiled in colonial infighting over the right to rule Honduras, a claim that put him in conflict with Pedro de Alvarado, captain general of Guatemala, who also claimed Honduras as part of his jurisdiction. Alvarado's claim ultimately turned out successful. In Montejo the Elder's absence, first in central Mexico, and then in Honduras, Montejo the Younger acted as lieutenant governor and captain general in Tabasco.

Conflict at Champoton

The Franciscan friar Jacobo de Testera arrived in Champoton in 1535 to attempt the peaceful incorporation of Yucatán into the Spanish Empire. Testera had been assured by the Spanish authorities that no military activity would be undertaken in Yucatán, while he was attempting its conversion to the Roman Catholic faith, and that no soldiers would be permitted to enter the peninsula. His initial efforts were proving successful when Captain Lorenzo de Godoy arrived in Champoton at the command of soldiers despatched there by Montejo the Younger. Godoy and Testera were soon in conflict and the friar was forced to abandon Champoton and return to central Mexico.

Godoy's attempt to subdue the Maya around Champoton was unsuccessful and the local Kowoj Maya resisted his attempts to assert Spanish dominance of the region.[115] This resistance was sufficiently tenacious that Montejo the Younger sent his cousin from Tabasco to Champoton to take command. His diplomatic overtures to the Champoton Kowoj were successful and they submitted to Spanish rule. Champoton was the last Spanish outpost in the Yucatán Peninsula; it was increasingly isolated and the situation there became difficult.

Conquest and settlement in northern Yucatán, 1540–46

In 1540, Montejo the Elder, who was now in his late 60s, turned his royal rights to colonise Yucatán over to his son, Francisco de Montejo the Younger. In early 1541, Montejo the Younger joined his cousin in Champoton; he did not remain there long, and quickly moved his forces to Campeche. Once there, Montejo the Younger, commanding between three and four hundred Spanish soldiers, established the first permanent Spanish town council in the Yucatán Peninsula. Shortly after establishing the Spanish presence in Campeche, Montejo the Younger summoned the local Maya lords and commanded them to submit to the Spanish Crown. A number of lords submitted peacefully, including the ruler of the Xiu Maya. The lord of the Canul Maya refused to submit and Montejo the Younger sent his cousin against them; Montejo himself remained in Campeche awaiting reinforcements.

Montejo the Younger's cousin met the Canul Maya at Chakan, not far from Tʼho. On 6 January 1542, he founded the second permanent town council, calling the new colonial town Mérida. On 23 January, Tutul Xiu, the lord of Mani, approached the Spanish encampment at Mérida in peace, bearing sorely needed food supplies. He expressed interest in the Spanish religion and witnessed a Roman Catholic mass celebrated for his benefit. Tutul Xiu was greatly impressed and converted to the new religion; he was baptised as Melchor and stayed with the Spanish at Mérida for two months, receiving instruction in the Catholic faith. Tutul Xiu was the ruler of the most powerful province of northern Yucatán and his submission to Spain and conversion to Christianity had repercussions throughout the peninsula, and encouraged the lords of the western provinces of the peninsula to accept Spanish rule. The eastern provinces continued to resist Spanish overtures.

Montejo the Younger next sent his cousin to Chauaca where most of the eastern lords greeted him in peace. The Cochua Maya resisted fiercely but were soon defeated by the Spanish. The Cupul Maya also rose up against the newly imposed Spanish domination, and also their opposition was quickly put down. Montejo continued to the eastern Ekab province, reaching the east coast at Pole. Stormy weather prevented the Spanish from crossing to Cozumel, and nine Spaniards drowned in the attempted crossing. Another Spanish conquistador was killed by hostile Maya. Rumours of this setback grew in the telling and both the Cupul and Cochua provinces once again rose up against their would-be European overlords. The Spanish hold on the eastern portion of the peninsula remained tenuous and a number of Maya polities remained independent, including Chetumal, Cochua, Cupul, Sotuta and the Tazes.

On 8 November 1546, an alliance of eastern provinces launched a coordinated uprising against the Spanish. The provinces of Cupul, Cochua, Sotuta, Tazes, Uaymil, Chetumal and Chikinchel united in a concerted effort to drive the invaders from the peninsula; the uprising lasted four months.[118] Eighteen Spaniards were surprised in the eastern towns, and were sacrificed. A contemporary account described the slaughter of over 400 allied Maya, as well as livestock. Mérida and Campeche were forewarned of the impending attack; Montejo the Younger and his cousin were in Campeche. Montejo the Elder arrived in Mérida from Chiapas in December 1546, with reinforcements gathered from Champoton and Campeche. The rebellious eastern Maya were finally defeated in a single battle, in which twenty Spaniards and several hundred allied Maya were killed. This battle marked the final conquest of the northern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula. As a result of the uprising and the Spanish response, many of the Maya inhabitants of the eastern and southern territories fled to the still unconquered Petén Basin, in the extreme south of the peninsula. The Spanish only achieved dominance in the north and the polities of Petén remained independent and continued to receive many refugees from the north.[119]

Petén Basin, 1618–97

The Petén Basin covers an area that is now part of Guatemala; in colonial times it originally fell under the jurisdiction of the Governor of Yucatán, before being transferred to the jurisdiction of the Audiencia Real of Guatemala in 1703.[120] The Itza kingdom centred upon Lake Petén Itzá had been visited by Hernán Cortés on his march to Honduras in 1525.[88]

Early 17th century

Following Cortés' visit, no Spanish attempted to visit the warlike Itza inhabitants of Nojpetén for almost a hundred years. In 1618 two Franciscan friars set out from Mérida on a mission to attempt the peaceful conversion of the still-pagan Itza in central Petén. Bartolomé de Fuensalida and Juan de Orbita were accompanied by some Christianised Maya. After an arduous six-month journey the travellers were well received at Nojpetén by the current Kan Ekʼ. They stayed for some days in an attempt to evangelise the Itza, but the Aj Kan Ekʼ refused to renounce his Maya religion, although he showed interest in the masses held by the Catholic missionaries. Attempts to convert the Itza failed, and the friars left Nojpetén on friendly terms with Kan Ekʼ. The friars returned in October 1619, and again Kan Ekʼ welcomed them in a friendly manner, but this time the Maya priesthood were hostile and the missionaries were expelled without food or water, but survived the journey back to Mérida.

In March 1622, the governor of Yucatán, Diego de Cardenas, ordered Captain Francisco de Mirones Lezcano to launch an assault upon the Itza; he set out from Yucatán with 20 Spanish soldiers and 80 Mayas from Yucatán.[123] His expedition was later joined by Franciscan friar Diego Delgado. In May the expedition advanced to Sakalum, southwest of Bacalar, where there was a lengthy delay while they waited for reinforcements.[124] En route to Nojpetén, Delgado believed that the soldiers' treatment of the Maya was excessively cruel, and he left the expedition to make his own way to Nojpetén with eighty Christianised Maya from Tipuj in Belize. In the meantime the Itza had learnt of the approaching military expedition and had become hardened against further Spanish missionary attempts.[125] When Mirones learnt of Delgado's departure, he sent 13 soldiers to persuade him to return or continue as his escort should he refuse. The soldiers caught up with him just before Tipuj, but he was determined to reach Nojpetén.[126] From Tipuj, Delgado sent a messenger to Kan Ekʼ, asking permission to travel to Nojpetén; the Itza king replied with a promise of safe passage for the missionary and his companions. The party was initially received in peace at the Itza capital,[127] but as soon as the Spanish soldiers let their guard down, the Itza seized and bound the new arrivals.[128] The soldiers were sacrificed to the Maya gods.[129] After their sacrifice, the Itza took Delgado, cut his heart out and dismembered him; they displayed his head on a stake with the others.[130] The fortune of the leader of Delgado's Maya companions was no better. With no word from Delgado's escort, Mirones sent two Spanish soldiers with a Maya scout to learn their fate. When they arrived upon the shore of Lake Petén Itzá, the Itza took them across to their island capital and imprisoned them. Bernardino Ek, the scout, escaped and returned to Mirones with the news.[128] Soon afterwards, on 27 January 1624, an Itza war party led by AjKʼin Pʼol caught Mirones and his soldiers off guard and unarmed in the church at Sakalum,[131] and killed them all. Spanish reinforcements arrived too late. A number of local Maya men and women were killed by Spanish attackers, who also burned the town.[132]

Following these killings, Spanish garrisons were stationed in several towns in southern Yucatán, and rewards were offered for the whereabouts of AjKʼin Pʼol. The Maya governor of Oxkutzcab, Fernando Kamal, set out with 150 Maya archers to track the warleader down; they succeeded in capturing the Itza captain and his followers, together with silverware from the looted Sakalum church and items belonging to Mirones. The prisoners were taken back to the Spanish Captain Antonio Méndez de Canzo, interrogated under torture, tried, and condemned to be hanged, drawn and quartered. They were decapitated, and the heads were displayed in the plazas of towns throughout the colonial Partido de la Sierra in what is now Mexico's Yucatán state.[133] These events ended all Spanish attempts to contact the Itza until 1695. In the 1640s internal strife in Spain distracted the government from attempts to conquer unknown lands; the Spanish Crown lacked the time, money or interest in such colonial adventures for the next four decades.[134]

Late 17th century

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of New Spain |

|

|

In 1692 Basque nobleman Martín de Ursúa y Arizmendi proposed to the Spanish king the construction of a road from Mérida southwards to link with the Guatemalan colony, in the process "reducing" any independent native populations into colonial congregaciones; this was part of a greater plan to subjugate the Lakandon and Manche Chʼol of southern Petén and the upper reaches of the Usumacinta River. The original plan was for the province of Yucatán to build the northern section and for Guatemala to build the southern portion, with both meeting somewhere in Chʼol territory; the plan was later modified to pass further east, through the kingdom of the Itza.[135]

The governor of Yucatán, Martín de Ursúa y Arizmendi, began to build the road from Campeche south towards Petén. At the beginning of March 1695, Captain Alonso García de Paredes led a group of 50 Spanish soldiers, accompanied by native guides, muleteers and labourers.[136] The expedition advanced south into Kejache territory, which began at Chunpich, about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) north of the modern border between Mexico and Guatemala.[137] He rounded up some natives to be moved into colonial settlements, but met with armed Kejache resistance. García decided to retreat around the middle of April.[138]

In March 1695, Captain Juan Díaz de Velasco set out from Cahabón in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, with 70 Spanish soldiers, accompanied by a large number of Maya archers from Verapaz, native muleteers, and four Dominican friars.[139] The Spanish pressed ahead to Lake Petén Itzá and engaged in a series of fierce skirmishes with Itza hunting parties.[140] At the lakeshore, within sight of Nojpetén, the Spanish encountered such a large force of Itzas that they retreated south, back to their main camp.[141] Interrogation of an Itza prisoner revealed that the Itza kingdom was in a state of high alert to repel the Spanish;[142] the expedition almost immediately withdrew back to Cahabón.[143]

In mid-May 1695 García again marched southwards from Campeche,[143] with 115 Spanish soldiers and 150 Maya musketeers, plus Maya labourers and muleteers; the final tally was more than 400 people, which was regarded as a considerable army in the impoverished Yucatán province.[144] Ursúa also ordered two companies of Maya musketeers from Tekʼax and Oxkʼutzkabʼ to join the expedition at Bʼolonchʼen Kawich, some 60 kilometres (37 mi) southeast of the city of Campeche.[145] At the end of May three friars were assigned to join the Spanish force, accompanied by a lay brother. A second group of Franciscans would continue onwards independently to Nojpetén to make contact with the Itzas; it was led by friar Andrés de Avendaño, who was accompanied by another friar and a lay brother.[146] García ordered the construction of a fort at Chuntuki, some 25 leagues (approximately 65 miles or 105 km) north of Lake Petén Itzá, which would serve as the main military base for the Camino Real ("Royal Road") project.[147]

The Sajkabʼchen company of native musketeers pushed ahead with the road builders from Tzuktzokʼ to the first Kejache town at Chunpich, which the Kejache had fled. The company's officers sent for reinforcements from García at Tzuktokʼ but before any could arrive some 25 Kejache returned to Chunpich with baskets to collect their abandoned food. The nervous Sajkabʼchen sentries feared that the residents were returning en masse and discharged their muskets at them, with both groups then retreating. The musketeer company then arrived to reinforce their sentries and charged into battle against approaching Kejache archers. Several musketeers were injured in the ensuing skirmish and, the Kejache retreated along a forest path without injury. The Sajkabʼchen company followed the path and found two more deserted settlements with large amounts of abandoned food. They seized the food and retreated back along the path.[148]

Around 3 August García moved his entire army forward to Chunpich,[149] and by October Spanish soldiers had established themselves near the source of the San Pedro River.[150] By November Tzuktokʼ was garrisoned with 86 soldiers and more at Chuntuki. In December 1695 the main force was reinforced with 250 soldiers, of which 150 were Spanish and pardo and 100 were Maya, together with labourers and muleteers.[151]

Avendaño's expedition, June 1695

In May 1695 Antonio de Silva had appointed two groups of Franciscans to head for Petén; the first group was to join up with García's military expedition. The second group was to head for Lake Petén Itza independently. This second group was headed by friar Andrés de Avendaño. Avendaño was accompanied by another friar, a lay brother, and six Christian Maya.[152] This latter group left Mérida on 2 June 1695.[153] Avendaño continued south along the course of the new road, finding increasing evidence of Spanish military activity. The Franciscans overtook García at Bʼukʼte, about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) before Tzuktokʼ.[154] On 3 August García advanced to Chunpich but tried to persuade Avendaño to stay behind to minister to the prisoners from Bʼukʼte. Avendaño instead split his group and left in secret with just four Christian Maya companions,[155] seeking the Chunpich Kejache that had attacked one of García's advance companies and had now retreated into the forest.[156] He was unable to find the Kejache but did manage to get information regarding a path that led southwards to the Itza kingdom. Avendaño returned to Tzuktokʼ and reconsidered his plans; the Franciscans were short of supplies, and the forcefully congregated Maya that they were charged with converting were disappearing back into the forest daily.[157] Antonio de Silva ordered Avendaño to return to Mérida, and he arrived there on 17 September 1695.[158] Meanwhile, the other group of Franciscans, led by Juan de San Buenaventura Chávez, continued following the roadbuilders into Kejache territory, through IxBʼam, Bʼatkabʼ and Chuntuki (modern Chuntunqui near Carmelita, Petén).[159]

San Buenaventura among the Kejache, September – November 1695

Juan de San Buenaventura's small group of Franciscans arrived in Chuntuki on 30 August 1695, and found that the army had opened the road southwards for another seventeen leagues (approximately 44.2 miles or 71.1 km), almost half way to Lake Petén Itzá, but returned to Chuntuki due to the seasonal rains.[160] San Buenaventura was accompanied by two friars and a lay brother.[161] With Avendaño's return to Mérida, provincial superior Antonio de Silva despatched two additional friars to join San Buenaventura's group. One of these was to convert the Kejache in Tzuktokʼ, and the other was to do the same at Chuntuki.[162] On 24 October San Buenaventura wrote to the provincial superior reporting that the warlike Kejache were now pacified and that they had told him that the Itza were ready to receive the Spanish in friendship.[163] On that day 62 Kejache men had voluntarily come to Chuntuki from Pakʼekʼem, where another 300 Kejache resided.[164] In early November 1695, friar Tomás de Alcoser and brother Lucas de San Francisco were sent to establish a mission at Pakʼekʼem, where they were well received by the cacique (native chief) and his pagan priest. Pakʼekʼem was sufficiently far from the new Spanish road that it was free from military interference, and the friars oversaw the building of a church in what was the largest mission town in Kejache territory. A second church was built at Bʼatkabʼ to attend to over 100 Kʼejache refugees who had been gathered there under the stewardship of a Spanish friar;[165] a further church was established at Tzuktokʼ, overseen by another friar.[166]

Avendaño's expedition, December 1695 – January 1696

Franciscan Andrés de Avendaño left Mérida on 13 December 1695, and arrived in Nojpetén around 14 January 1696, accompanied by four companions.[167] From Chuntuki they followed an Indian trail that led them past the source of the San Pedro River and across steep karst hills to a watering hole by some ruins.[168] From there they followed the small Acté River to a Chakʼan Itza town called Saklemakal.[169] They arrived at the western end of Lake Petén Itzá to an enthusiastic welcome by the local Itza. The following day, the current Aj Kan Ekʼ travelled across the lake with eighty canoes to greet the visitors at the Chakʼan Itza port town of Nich, on the west shore of Lake Petén Itza.[171] The Franciscans returned to Nojpetén with Kan Ekʼ and baptised over 300 Itza children over the following four days. Avendaño tried to convince Kan Ekʼ to convert to Christianity and surrender to the Spanish Crown, without success. The king of the Itza, cited Itza prophecy and said the time was not yet right.

On 19 January AjKowoj, the king of the Kowoj, arrived at Nojpetén and spoke with Avendaño,[172] arguing against the acceptance of Christianity and Spanish rule.[173] The discussions between Avendaño, Kan Ekʼ and AjKowoj exposed deep divisions among the Itza.[174] Kan Ekʼ learnt of a plot by the Kowoj and their allies to ambush and kill the Franciscans, and the Itza king advised them to return to Mérida via Tipuj.[175] The Spanish friars became lost and suffered great hardships, including the death of one of Avendaño's companions,[176] but after a month wandering in the forest found their way back to Chuntuki, and from there returned to Mérida.[177]

Battle at Chʼichʼ, 2 February 1696

By mid-January Captain García de Paredes had arrived at the advance portion of the Camino Real at Chuntuki.[178] By now he only had 90 soldiers plus labourers and porters.[179] Captain Pedro de Zubiaur, García's senior officer, arrived at Lake Petén Itza with 60 musketeers, two Franciscans, and allied Yucatec Maya warriors.[180] They were also accompanied by about 40 Maya porters.[181] They were approached by about 300 canoes carrying approximately 2,000 Itza warriors.[182] The warriors began to mingle freely with the Spanish party and a scuffle then broke out; a dozen of the Spanish party were forced into canoes, and three of them were killed. At this point the Spanish soldiers opened fire with their muskets, and the Itza retreated across the lake with their prisoners, who included the two Franciscans.[183] The Spanish party retreated from the lake shore and regrouped on open ground where they were surrounded by thousands of Itza warriors. Zubiaur ordered his men to fire a volley that killed between 30 and 40 Itzas. Realising that they were hopelessly outnumbered, the Spanish retreated towards Chuntuki, abandoning their captured companions to their fate.[184]

Martín de Ursúa was now convinced that Kan Ekʼ would not surrender peacefully, and he began to organise an all-out assault on Nojpetén. Work on the road was redoubled and about a month after the battle at Chʼichʼ the Spanish arrived at the lakeshore, now supported by artillery. Again a large number of canoes gathered, and the nervous Spanish soldiers opened fire with cannons and muskets; no casualties were reported among the Itza, who retreated and raised a white flag from a safe distance.[184]

Expedition from Verapaz, February – March 1696

Oidor Bartolomé de Amésqueta led the next Guatemalan expedition against the Itza. He marched his men from Cahabón to Mopán, arriving on 25 February 1696.[186] On 7 March, Captain Díaz de Velasco led a party ahead to the lake; he was accompanied by two Dominican friars and by AjKʼixaw, an Itza nobleman who had been taken prisoner on Díaz's previous expedition.[187] When they drew close to the shore of Lake Petén Itzá, AjKʼixaw was sent ahead as an emissary to Nojpetén.[188] Díaz's party was lured into an Itza trap and the expedition members were killed to a man. The two friars were captured and sacrificed. The Itza killed a total of 87 expedition members, including 50 soldiers, two Dominicans and about 35 Maya helpers.[189]

Amésqueta left Mopán three days after Díaz and followed Díaz's trail to the lakeshore. He arrived at the lake over a week later with 36 men. As they scouted along the south shore near Nojpetén they were shadowed by about 30 Itza canoes and more Itzas approached by land but kept a safe distance.[190] Amésqueta was extremely suspicious of the small canoes being offered by the Itza to transport his party across to Nojpetén; as nightfall approached Amésqueta retreated from the lakeshore and his men took up positions on a small hill nearby.[191] In the early hours of the morning he ordered a retreat by moonlight.[192] At San Pedro Martír he received news of an Itza embassy to Mérida in December 1695, and an apparent formal surrender of the Itza to Spanish authority.[193] Unable to reconcile the news with the loss of his men, and with appalling conditions in San Pedro Mártir, Amésqueta abandoned his unfinished fort and retreated to Guatemala.[194]

Assault on Nojpetén

The Itzas' continued resistance had become a major embarrassment for the Spanish colonial authorities, and soldiers were despatched from Campeche to take Nojpetén once and for all.[195] Martín de Urzúa y Arizmendi arrived on the western shore of Lake Petén Itzá with his soldiers on 26 February 1697, and once there built the heavily armed galeota attack boat.[196] The galeota carried 114 men and at least five artillery pieces.[197] The piragua longboat used to cross the San Pedro River was also transported to the lake to be used in the attack on the Itza capital.[198]

On 10 March a number of Itza and Yalain emissaries arrived at Chʼichʼ to negotiate with Ursúa.[199] Kan Ekʼ then sent a canoe with a white flag raised bearing emissaries, who offered peaceful surrender. Ursúa received the embassy in peace and invited Kan Ekʼ to visit his encampment three days later. On the appointed day Kan Ekʼ failed to arrive; instead Maya warriors amassed both along the shore and in canoes upon the lake.

A waterbourne assault was launched upon Kan Ek's capital on the morning of 13 March.[201] Ursúa boarded the galeota with 108 soldiers, two secular priests, five personal servants, the baptised Itza emissary AjChan and his brother-in-law and an Itza prisoner from Nojpetén. The attack boat was rowed east towards the Itza capital; half way across the lake it encountered a large fleet of canoes spread in an arc across the approach to Nojpetén – Ursúa simply gave the order to row through them. A large number of defenders had gathered along the shore of Nojpetén and on the roofs of the city.[202] Itza archers began to shoot at the invaders from the canoes. Ursúa ordered his men not to return fire but arrows wounded a number of his soldiers; one of the wounded soldiers discharged his musket and at that point the officers lost control of their men. The defending Itza soon fled from the withering Spanish gunfire.[203]

The city fell after a brief but bloody battle in which many Itza warriors died; the Spanish suffered only minor casualties. The Spanish bombardment caused heavy loss of life on the island;[204] the surviving Itza abandoned their capital and swam across to the mainland with many dying in the water.[205] After the battle the surviving defenders melted away into the forests, leaving the Spanish to occupy an abandoned Maya town.[195] Martín de Ursúa planted his standard upon the highest point of the island and renamed Nojpetén as Nuestra Señora de los Remedios y San Pablo, Laguna del Itza ("Our Lady of Remedy and Saint Paul, Lake of the Itza").[206] The Itza nobility fled, dispersing to Maya settlements throughout Petén; in response the Spanish scoured the region with search parties.[207] Kan Ekʼ was soon captured with help from the Yalain Maya ruler Chamach Xulu;[208] The Kowoj king (Aj Kowoj) was also soon captured, together with other Maya nobles and their families.[204] With the defeat of the Itza, the last independent and unconquered native kingdom in the Americas fell to the European colonisers.[209]

See also

Notes

- Belma has been tentatively identified with the modern settlement and Maya archaeological site of El Meco.[104]

Citations

- Quezada 2011, p. 13.

- Quezada 2011, p. 14.

- White and Hood 2004, p. 152.

Quezada 2011, p. 14. - Thompson 1966, p. 25.

- Quezada 2011, p. 15.

- Quezada 2011, pp. 14–15.

- Lovell 2005, p. 17.

- Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 46–47.

- Rice and Rice 2009, p. 5.

- Quezada 2011, p. 16.

- Quezada 2011, p. 17.

- White and Hood 2004, p. 152.

- Schwartz 1990, p. 17.

- Schwartz 1990, p. 18.

- Estrada-Belli 2011, p. 52.

- Coe 1999, p. 31.