Law of Australia

The legal system of Australia consists of multiple forms of law. The country's legal system comprises of a written constitution, unwritten constitutional conventions, statutes, regulations, and the judicially determined common law.

The Australian Constitution is the legal foundation of the Commonwealth of Australia and sets out a federal system of government, dividing power between the Federal Government and the States and Territories, each of which are separate jurisdictions and have their own system of courts and parliaments. Australia's constitutional framework is a combination of elements of the Westminster and United States constitutional arrangements; sometimes described as 'Washminister'.[1] The federal legislature has the power to pass laws with respect to a number of express areas,[2] which apply to the whole of Australia and override any State laws to the extent of any inconsistency.[3] However, beyond those express areas the States’ legislatures plenary power.[4]

The common law system in Australia is derived from the common law system of English law, and is enforced uniformly across Australian jurisdictions (subject to augmentation by Commonwealth and State statutes).[5]

The High Court of Australia is the highest court in Australia. It has the final say on all exercise of judicial power. It hears appeals from inferior state & federal courts, as well as matters of original jurisdiction.[6]

History

Reception of English law

The legal institutions and traditions of Australian law are monocultural in character, reflecting its English origins.[7] When the British arrived in Australia, they considered the continent to be terra nullius, or land belonging to no-one, on the basis that the Aboriginal peoples already inhabiting the continent were not cohesively organised for a treaty to be struck with any single representation of their peoples.[8] Under the English conception of international law at the time, when uninhabited lands were settled by English subjects the laws of England immediately applied to the settled lands.[9] As such, Aboriginal laws and customs, including native title to land, were not recognised. The reception of English law was clarified by the Australian Courts Act 1828 (UK), which provided that all laws and statutes in force in England at the date of enactment should be applied in the courts of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) so far as those laws were applicable. Since Queensland and Victoria were originally part of New South Wales, the same date applies in those States for the reception of English law. South Australia adopted a different date for reception,[10] as did Western Australia.[11]

The earliest civil and criminal courts established from the beginnings of the colony of New South Wales were rudimentary, adaptive and military in character. Although legality was not always observed, the courts limited the powers of the Governor, and the law of the colony was at times more egalitarian than in Britain.[12]

By 1824, a court system based in essence on the English model had been established through Acts of the British Parliament.[13] The New South Wales Act 1823 provided for the establishment of a Supreme Court with the power to deal with all criminal and civil matters "as fully and amply as Her Majesty's Court of King's Bench, Common Pleas and Exchequer at Westminster".[13] Inferior courts were also established, including courts of General or Quarter Sessions, and Courts of Requests.

Representative government emerged in the 1840s and 1850s, and a considerable measure of autonomy was given to local legislatures in the second half of the nineteenth century.[14] Colonial Parliaments introduced certain reforms such as secret ballots and female suffrage, which were not to occur in Britain until many years later. Nevertheless, Acts of the United Kingdom Parliament extending to the colonies could override contrary colonial legislation and would apply by "paramount force".[15] New doctrines of English common law continued to be treated as representing the common law of Australia. For example, the doctrine of the famous case of Donoghue v Stevenson from which the modern negligence law derived, was treated as being latent already within the common law at the time of reception.[16]

Federation and divergence

Following a number of constitutional conventions during the 1890s to develop a federal nation from the several colonies, the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (UK) was passed and came into force on 1 January 1901. Thus, although a British statute, this became Australia's Constitution.

Following federation, Britain's role in the government of Australia became increasingly nominal in the 20th century. However, there was little momentum for Australia to obtain legislative independence. The Australian States did not participate in the conferences leading up to the Statute of Westminster 1931, which provided that no British Act should be deemed to extend to the dominions without the consent of the dominion. The Australian Government did not invoke the provisions of the statute until 1942. The High Court also followed the decisions of the Privy Council during the first half of the twentieth century.

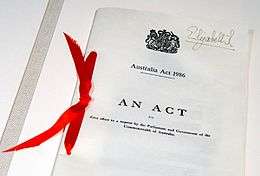

Complete legislative independence was finally established by the Australia Act 1986, passed by the United Kingdom Parliament. It removed the possibility of legislation being enacted at the consent and request of a dominion, and applied to the States as well as the Commonwealth. It also provided for the complete abolition of appeals to the Privy Council from any Australian court. The Australia Act represented an important symbolic break with Britain, emphasised by Queen Elizabeth II's visit to Australia to sign the legislation in her legally distinct capacity as the Queen of Australia.

Legislative independence has been paralleled by a growing divergence between Australian and English common law in the last quarter of the 20th century.[17] In addition, a large body of English law received in Australia has been progressively repealed in state parliaments, such as in New South Wales by the Imperial Acts Application Act 1969.

Australian Republicanism emerged as a movement in the 1990s, which aims eventually to change Australia's status as a constitutional monarchy to a republican form of government.

Sources of law

Discussion of the sources of Australian law is complicated by the federal structure, which creates two sources of written constitutional law: state and federal—and two sources of general statute law, with the federal Constitution determining the validity of State and federal statutes in cases where the two jurisdictions might overlap.

Constitutional law

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Australian colonies became a federation in 1901 through the passing of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act by the British Parliament. The federal constitution was the product of nearly ten years of discussion, "with roots in both the British legal tradition and Australian democracy".[18]

The Constitution provided for the legislative power of the Commonwealth to be vested in a federal Parliament consisting of the Queen, a Senate and a House of Representatives. The role of the Queen in the legislative process lies in her responsibility to grant Royal Assent, a power exercised on her behalf by the Governor-General. The Queen has the highest role in the Assent to legislation in contemporary Australia. Without the Royal Assent there can be no law created or amended within the dominion of the Commonwealth of Australia and its States and Territories.

The legislative powers of the federal Parliament are limited to those set out under an enumerated list of subject matters in section 51 of the Constitution. These powers include a power to legislate on matters "incidental" to the other powers,[19] similar to the United States necessary and proper clause. The Parliament of the Commonwealth can also legislate on matters referred to it by the Parliament of one or more States.[20] In contrast, with a few exceptions[21] the State legislatures generally have plenary power to enact laws on any subject. However, federal laws prevail over State laws where there is any inconsistency.[3] The High Court of Australia has jurisdiction to determine disputes about whether a law is within power and consistent with the Constitution.[22]

Chapter III of the Constitution required the creation of the High Court and confers power to establish other federal courts and to vest federal jurisdiction in State courts.

Australian courts could permit an appeal to the Privy Council on constitutional matters. The right of appeal from the High Court to the Privy Council was only abolished in 1975,[23] and from State courts in 1986.[24]

Australia does not have a constitutional bill of rights and there are few express rights guaranteed by the Constitution. However, certain indirect protections have been recognised by implication or as a consequence of other constitutional principles. For example, there is an implied guarantee of freedom of political communication.[25] Additionally, rights are protected indirectly through the separation of powers, which requires courts to be sufficiently independent and impartial from the other branches of government. Human rights in Australia are generally protected through statutes and the common law.

Statute law

If the government agrees that the changes are worthwhile, a Bill is drafted, usually by Parliamentary Counsel. The Bill is read and debated in both houses of parliament before it is either rejected, changed, or approved. An approved Bill must then receive the assent then handed down to either the Governor (State) or the Governor-General (Commonwealth). Parliament often delegates legislation to local councils, statutory authorities and government departments, for sub or minor statute laws or rules such as Road Rules, but all law is answerable to the Commonwealth Constitution.

Most statutes are meant to be applied in the main not by legal practitioners and judges but by administrative decision makers.[26] Certain laws receive more judicial interpretation than others, either because more is at stake or because those who are affected are in a position to take the matter to court. Whilst the meanings presented to the court are often those that benefit the litigants themselves,[27] the courts are not bound to select one of the interpretations offered by the parties.[28]

Australian courts have departed from the traditional approach of interpreting statutes (the literal rule, the golden rule,[29] and the mischief rule[30]). The dominant approach is that rules are not to be applied rigidly because the overriding goal is to interpret the statute in accordance with the intentions of Parliament.[31] This so-called "purposive approach" has been reinforced by statute.[32] Legislation in all States and Territories allows recourse to extrinsic materials.[33]

In each Australian state, including the Commonwealth and the Australian Capital Territory, there is an official compilation of all new laws enacted by the Parliaments in such states. The Western Australian Consolidated Acts, Northern Territory Consolidated Acts, Queensland Consolidated Acts, South Australian Current Acts, New South Wales Consolidated Acts, Victorian Consolidated Acts, and the Tasmanian Consolidated Acts are the official compilation of laws and statutes in such Australian states. They contain statutes, Acts of Parliament, criminal law and many major topic areas. They are all enacted in chronological order and are normally enacted in statute.

The Commonwealth of Australia Consolidated Acts are all of the federal statutes and laws, including federal criminal law, enacted by the Parliament of Australia. The Australian Capital Territory Consolidated Acts are all of the enacted laws and statutes of the Australian Capital Territory that are enacted by the Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly.

Common law

Common law in Australia, like in other former British colonies, is the body of law developed from thirteenth century England to the present day, as case law or precedent, by judges, courts, and tribunals. However, after over a century of federation, there is a substantial divergence between English and Australian common law.[34]

The High Court of Australia has a general appellate jurisdiction from the State Supreme Courts per s 73(ii) of the Australian Constitution.[35] The High Court's appellate jurisdiction ensures a uniform Australian common law.[5]:p 563 The High Court also has original jurisdiction for matters in s 75 of the Australian Constitution.[36]

Until 1963, the High Court regarded decisions of the House of Lords binding,[37] and there was substantial uniformity between Australian and English common law. In 1978, the High Court declared that it was no longer bound by decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.[38][39]

International law

The status of treaties as a source of Australian law has been controversial. Australia has entered many treaties.[40] The signature or ratification of a treaty, (apart from one terminating a state of war), is not directly or automatically incorporated into Australian domestic law. Treaties do not impose obligations upon individuals or the government in the absence of domestic legislation.

The role of treaties in the development of Australia's common law, or even in the interpretation of domestic statutes is controversial; however, it is accepted as legitimate that treaties may be called upon by Australian Statues as an interpretive aid to their enactment.[41]

Through reliance upon the external affairs power, matters that are the subject of a treaty may be legislated upon by the Commonwealth Parliament; even in the absence of that subject among the enumerated heads of legislative power in s51 of the constitution.

Through the external affairs power, can be incorporated into Australian law by the Commonwealth parliament through reliance upon the external affairs power;

Areas of law

The main substantive areas of law in Australia include:

- Administrative law - which deals with the laws governing the lawful exercise of Executive power and the review of government decisions.

- Constitutional law - which governs issues arising under the Australian Constitution, such as the validity of laws and the separation of powers.

- Contract law - which governs agreements, and which is derived from and very similar to English contract law.

- Corporations law - which includes the incorporation and regulation of companies and other collective entities.

- Criminal law - which deals with crime and punishment, and is principally regulated by laws of the States and territories.

- Environment and planning law - which governs land use and planning, and environmental protection, and is largely regulated by the States.

- Equity - which is primarily concerned with unconscionable conduct, and supplements other areas of civil law such as contract and property law.

- Family law - which is regulated by federal legislation. Disputes are usually heard in the Family Court of Australia.

- Insolvency law - which governs the winding up of corporations, and is regulated largely by the federal Corporations Act 2001.

- Intellectual property law - which governs copyright, designs, and patents, and is regulated largely by federal statutes.

- Property law - which governs rights and obligations regarding personal and real property.

- Tax law - which arises from federal and State statutes regulating taxation in Australia.

- Tort law - which governs civil wrongs such as negligence, trespass, defamation, nuisance, conversion, and detinue.

References

- corporateName=Commonwealth Parliament; address=Parliament House, Canberra. "Bicameral representation". www.aph.gov.au. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Constitution (Cth) s 51 Legislative powers of the Parliament.

- Constitution (Cth) s 109 Inconsistency of laws.

- Rizeq v Western Australia [2017] HCA 23 at [136] per Edelman J (21 June 2017), High Court (Australia)

- Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation ("Political Free Speech case") [1997] HCA 25, (1997) 189 CLR 520 (8 July 1997).

- Constitution (Cth) s 73 Appellate jurisdiction of High Court.

- Patrick Parkinson, Tradition and Change in Australian Law (Sydney: LBC Information Services, 2001) at 6.

- Australian Law Reform Commission, "Ch 4. Aboriginal Customary Laws and Anglo-Australian Law After 1788", Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws (ALRC Report 31), retrieved 27 August 2019

- Case 15 - Anonymous (1722) 2 Peer William's Reports 75, 24 ER 646, King's Bench (UK).

- Acts Interpretation Act 1915 (SA), s 48.

- Interpretation Act 1918 (WA), s 43.

- Kercher, B (1995). An Unruly Child: A History of Law in Australia. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781863738910. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017. at 7, 52. Kercher refers to the case of Henry Kable, who successfully sued the captain of the ship Alexander. Cable v Sinclair [1788] NSWSupC 7, [1788] NSWKR 7.

- New South Wales Act 1823 (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2017, retrieved 18 September 2017 (IMP); Australian Courts Act 1828 (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2016, retrieved 18 September 2017 (IMP).

- Great Reform Act 1832; Australian Constitutions Act 1842 (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2016, retrieved 7 May 2020 (IMP); Australian Constitutions Act (No 2) (IMP).

- Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2016, retrieved 7 May 2020 (Imp), s 2.

- State Government Insurance Commission v Trigwell [1979] HCA 40, (1979) 142 CLR 617.

- M. Ellinghaus, A. Bradbrook and A. Duggan (eds.), The Emergence of Australian Law (Butterworths: Sydney, 1989) at 70.

- Kercher, B (1995). An Unruly Child: A History of Law in Australia. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781863738910. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017. at 157.

- Constitution (Cth) s 51 Placitum xxxix.

- Constitution (Cth) s 51 Placitum xxxvii.

- Constitution (Cth) s 52 Exclusive powers of the Parliament.

- See, e.g. Pape v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2009] HCA 23, (2009) 238 CLR 1.

- Privy Council (Appeals from the High Court) Act 1975 (Cth).

- Australia Act 1986, archived from the original on 24 September 2017, retrieved 18 September 2017 (IMP).

- Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth [1992] HCA 45, (1992) 177 CLR 106.

- Barnes, Jeffrey W. "Statutory Interpretation, Law Reform and Sampford's Theory of the Disorder of Law Part One". Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) (1994) 22 Federal Law Review 116; Part Two, archived from the original on 19 March 2018, retrieved 19 March 2018, (1995) 23 Federal Law Review 77. - Dennis C. Pearce and R. S. Geddes, Statutory Interpretation in Australia (4th edition, Butterworths: Sydney, 1996), p. 3.

- Saif Ali v Sydney Mitchell v Co [1978] UKHL 6, [1980] AC 198 at 212.

- Grey v Pearson [1857] EngR 335; (1857) 6 HLC 61 at 106.

- Heydon's Case [1584] Eng R 9; (1584) 3 Co Rep 7a at 7b.

- Cooper Brookes (Wollongong) Pty Ltd v FCT [1981] HCA 26, (1981) 147 CLR 297 at 321 per Justices Mason and Wilson.

- For example, Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 15AA.

- For example, Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 15AB.

- Finn, Paul. "Common Law Divergences". Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017. (2013) 37 Melbourne University Law Review 509.

- Constitution (Cth) s 73.

- Constitution (Cth) s 75.

- Parker v The Queen [1963] HCA 14, (1963) 111 CLR 610 per Dixon J at [17].

- Viro v The Queen [1978] HCA 9, (1978) 141 CLR 88.

- Geddes, R. "The Authority of Privy Council Decisions in Australian Courts" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2016. (1978) 9 Federal Law Review 427.

- "Australian Treaties Library". AustLII. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "Treaty making process". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

Further reading

- Rosemary Barry (ed.), The Law Handbook (Redfern Legal Centre Publishing: Sydney, 2007).

- John Carvan, Understanding the Australian Legal System (Lawbook Co.: Sydney, 2002).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Law of Australia. |

| Library resources about Law of Australia |