Transport in Australia

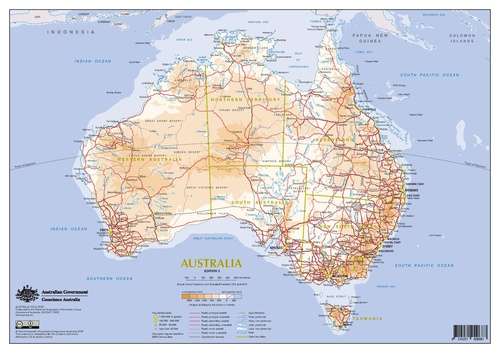

There are many forms of transport in Australia. Australia is highly dependent on road transport. There are more than 300 airports with paved runways. Passenger rail transport includes widespread commuter networks in the major capital cities with more limited intercity and interstate networks. The Australian mining sector is reliant upon rail to transport its product to Australia's ports for export.

Road transport

Road transport is an essential element of the Australian transport network, and an enabler of the Australian economy. There is a heavy reliance on road transport due to Australia's large area and low population density in considerable parts of the country.[1]

Another reason for the reliance upon roads is that the Australian rail network has not been sufficiently developed for a lot of the freight and passenger requirements in most areas of Australia. This has meant that goods that would otherwise be transported by rail are moved across Australia via road trains. Almost every household owns at least one car, and uses it most days.[2]

There are 3 different categories of Australian roads. They are federal highways, state highways and local roads. The road network comprises a total of 913,000 km broken down into:[3]

- paved: 353,331 km (including 3,132 km of expressways)

- unpaved: 559,669 km (1996 estimate)

Victoria has the largest network, with thousands of arterial (major, primary and secondary) roads to add.

The majority of road tunnels in Australia have been constructed since the 1990s to relieve traffic congestion in metropolitan areas, or to cross significant watercourses.

Cars

Australia has the second highest level of car ownership in the world. It has three to four times more road per capita than Europe and seven to nine times more than Asia. Australia also has the third highest per capita rate of fuel consumption in the world. Melbourne is the most car-dependent city in Australia, according to a data survey in the 2010s. Having over 110,000 more cars driving to and from the city each day than Sydney. Perth, Adelaide and Brisbane are rated as being close behind. All these capital cities are rated among the highest in this category in the world (car dependency).[4] The distance travelled by car (or similar vehicle) in Australia is among the highest in the world, being exceeded by USA and Canada.[1]

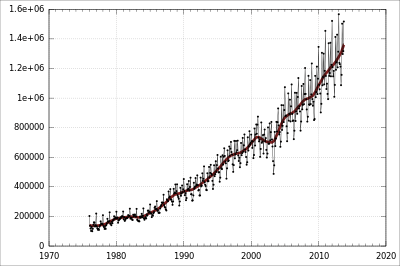

Electric vehicles

The adoption of plug-in electric vehicles in Australia is driven by customer demand due to the lack of government policies or monetary incentives to support the adoption and deployment of low or zero emission vehicles.

The total stock of plug-in electric vehicles is almost 12,000 with 6,718 of these electric cars sold in 2019 alone with the other sales occurring between 2012 and 2018.[7][8][9] A further 14,253 electric vehicles were registered in early 2020 which is nearly double the registrations of the previous year.[10] The Mitsubishi Outlander P-HEV was the country's top selling plug-in electric vehicle, with over 2,906 plug-in hybrid SUVs sold through March 2018.[11] However, Tesla accounted for 70% of the 6,718 electric car sales in 2019 with the Tesla Model 3 compromising two-thirds of electric car sales in the year.[12] The electric Tesla Model X and Model 3 are Australia's second and third most safest cars.[13] While the Mercedes-Benz all-electric EQC was named the best car in Australia in 2019.[14]

Victoria is Australia's most important electric vehicle market with the most electric vehicle purchases in Australia between 2011 and 2017 with a total of 1,324 car sales.[15] Victoria is also Australia's most important electric vehicle market because it had the most electric vehicle chargers in the country.[15] Similarly, Victoria's capital city Melbourne, had the highest concentration of electric vehicle chargers in Australia in 2017.[15] Victoria had 403 electric vehicle chargers in 2019 with another 31 expected to be constructed by the end of 2020.[16] Victoria almost doubled the electric vehicle charger network from 216 chargers in 2018 to 403 chargers in 2019.[16][15] Victoria also manufactures electric vehicles with a commercial electric vehicle manufacturing facility to be established in Victoria in 2021, producing 2,400 vehicles per year.[17] The Victorian company SEA Electric also manufactures electric trucks and other vehicles for domestic and international markets.[18][19] Overall, Victoria, Australian Capital Territory/New South Wales, South Australia and Tasmania represent the largest markets in the country for electric car sales.[15]

The 2018 Electric Vehicle Council report Recharging the Economy, stated a high adoption of electric vehicles has the potential to boost GDP by $2.9 billion and support 13,400 jobs by 2030, and has other positive economic effects including lower fuel costs and better fuel security, improved public health and growth of EV supply chains.[20] A study in 2020 by ClimateWorks Australia, stated that at least 50% of all new cars sold in 2030 will need to be electric vehicles to remain within 2C of global warming by 2050.[21] The study further found that Australia will require an accelerated rollout of electric vehicles to transition to net zero emissions by 2050 and to ensure 100% renewable energy by 2035.[21]Public transport in Australia

.jpg)

Commuter rail

Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide have extensive commuter rail networks which have grown and expanded over time. Australian commuter rail typically operates with bidirectional all day services with Sydney, Melbourne, and to a lesser extent Perth and Brisbane’s systems operating with much higher frequencies, particularly in their underground cores. Sydney Trains operates the busiest system in the country with approximately 1 million trips per day. Metro Trains Melbourne operates a larger system albeit with a lower number of trips.

Trams and light rail

Trams have historically operated in many Australian towns and cities, with the majority of these being shut down before the 1970s in the belief that more widespread car ownership would render them unnecessary. Melbourne is a major exception and today has the largest tram network of any city in the world. Adelaide also retained one tram service - the Glenelg tram line, since extended from 2008 onwards to Hindmarsh and the East End. Trams had operated in a number of major regional cities including Ballarat, Bendigo, Brisbane, Broken Hill, Fremantle, Geelong, Hobart, Kalgoorlie, Launceston, Maitland, Newcastle, Perth, Rockhampton, Sorrento, Sydney and St Kilda.

A modern light rail system opened in Sydney in 1997 with the conversion of a disused section of a freight railway line into what is now part of the Dulwich Hill Line. The CBD and South East Light Rail in Sydney opened to Randwick in December 2019 and Kingsford in April 2020. A light rail system opened on the Gold Coast in 2014. A line opened in Newcastle in February 2019 and a line in Canberra opened in April 2019.[22][23]

Rapid transit

Sydney is the only city in Australia with a rapid transit system. The Sydney Metro network currently consists of one 36 km driverless line, connecting Tallawong and Chatswood. The line will eventually connect with the Sydney Metro City & Southwest to form a 66 km network with 31 metro stations. The Sydney Metro West is also currently in planning stages.

Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth's commuter systems are all partially underground and reflect some aspects of typical rapid transit systems, particularly in the city centres.

Intra-city public transport networks

The following table presents an overview of multi-modal intra-city public transport networks in Australia's larger cities. The only Australian capital cities without multi-modal networks is Darwin, which relies entirely on buses, and Hobart, which has sections of derelict railway. The table does not include tourist or heritage transport modes (such as the private monorail at Sea World or the tourist Victor Harbor Horse Drawn Tram).

| City | Overview | Integrated network name | Buses | Urban rail/Commuter rail | Light rail[24] | Watercraft[25] | Rapid transit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adelaide | Public transport in Adelaide | Adelaide Metro | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Brisbane | Public transport in Brisbane | TransLink | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Canberra | Public transport in Canberra | Transport Canberra | Yes | Yes | |||

| Darwin | Public transport in Darwin | Darwinbus | Yes | Limited | |||

| Gold Coast | Public transport on the Gold Coast | TransLink | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Hobart | Transport in Hobart | Metro Tasmania | Yes | Yes | |||

| Melbourne | Public transport in Melbourne | Public Transport Victoria | Yes | Yes | Yes | Limited | |

| Newcastle | Transport in Newcastle | Newcastle Transport (under Transport for NSW) | Yes | Limited | Yes | Limited | |

| Perth | Public transport in Perth | Transperth | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Sydney | Public transport in Sydney | Transport for NSW | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

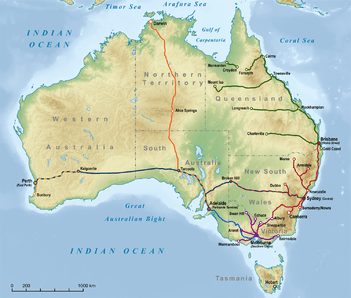

Intercity rail transport

State Government owned rail services: Journey Beyond lines:

The railway network is large, comprising a total of 33,819 km (2,540 km electrified) of track: 3,719 km broad gauge, 15,422 km standard gauge, 14,506 km narrow gauge and 172 km dual gauge. Rail transport started in the various colonies at different dates. Privately owned railways started the first lines, and struggled to succeed on a remote, huge, and sparsely populated continent, and government railways dominated. Although the various colonies had been advised by London to choose a common gauge, the colonies ended up with different gauges.

Inter-state rail services

Journey Beyond operates four trains: the Indian Pacific (Sydney-Adelaide-Perth), The Ghan (Adelaide-Alice Springs-Darwin), The Overland (Melbourne-Adelaide),[26] and the Great Southern (Brisbane-Melbourne-Adelaide). NSW Government owned NSW TrainLink services link Brisbane, Canberra, Melbourne, Dubbo, Broken Hill, Armidale, Moree and Griffith to Sydney. Since the extension of the Ghan from Alice Springs to Darwin was completed in 2004, all mainland Australian capital cities are linked by standard gauge rail, for the first time.

Intra-state and city rail services

There are various state and city rail services operated by a combination of government and private entities, the most prominent of these include V/Line (regional trains and coaches in Victoria); Metro Trains Melbourne (suburban services in Melbourne); NSW TrainLink (regional trains and coaches in New South Wales); Sydney Trains (suburban services in Sydney); Queensland Rail (QR) operating long distance Traveltrain services and the City network in South-East Queensland, and Transwa operating train and bus services in Western Australia.

In Tasmania, TasRail operates a short haul narrow gauge freight system, that carries inter-modal and bulk mining goods. TasRail is government owned (by the State of Tasmania) and is going through a significant below and above rail upgrades with new locomotives and wagons entering service. Significant bridge and sleeper renewal has also occurred. The Tasmanian Government also operates the West Coast Wilderness Railway as a tourist venture over an isolated length of track on Tasmania's West Coast.

Mining railways

Six heavy-duty mining railways carry iron ore to ports in the northwest of Western Australia. These railways carry no other traffic, and are isolated by deserts from all other railways. The lines are standard gauge and are built to the heaviest US standards. Each line is operated by one of either BHP, Rio Tinto, Fortescue Metals Group and Hancock Prospecting.

A common carrier railway was proposed to serve the port of Oakajee just north of Geraldton, but this was later cancelled after a collapse in the iron ore price.

Cane railways

In Queensland, 19 sugar mills are serviced by ~3,000 km of narrow gauge (2 ft / 610 mm gauge) cane tramways that deliver sugar cane to the mills.

Pipelines

There are several pipeline systems including:

- Crude oil: 2,500 km

- Petroleum products: 500 km

- Natural gas: 5,600 km

- Water

- Perth to Kalgoorlie - Goldfields Water Supply Scheme

- Morgan on the Murray River to Whyalla, Port Lincoln - Morgan–Whyalla pipeline

- Mannum on the Murray River to Adelaide - Mannum–Adelaide pipeline

- Waranga Western Channel, near Colbinabbin to Bendigo and Ballarat - Goldfields Superpipe

Projects under construction or planned:

Victoria

- Goulburn River to Sugarloaf Reservoir, Melbourne (North-South Pipeline, alternatively called the Sugarloaf Pipeline) - was connected to Melbourne in February 2010.[27]

- Wimmera-Mallee Pipeline - construction commenced in November 2006 and was completed in April 2010.[28]

- Melbourne to Geelong Pipeline - construction was completed in March 2012.[29]

- Rocklands Reservoir to Grampian Headworks Pipeline (Hamilton - Grampians Pipeline) - construction commenced December 2008, expected completion in 2010.

Waterways

Between 1850 and 1940, paddle steamers were used extensively on the Murray-Darling Basin to transport produce, especially wool and wheat, to river ports such as Echuca, Mannum and Goolwa. However, the water levels of the inland waterways are highly unreliable, making the rivers impassable for large parts of the year. A system of locks was created largely to overcome this variability, but the steamers were unable to compete with rail, and later, road transport. Traffic on inland waterways is now largely restricted to private recreational craft.[30]

Ports and harbours

Mainland

General

- Adelaide, Brisbane, Cairns, Darwin, Fremantle, Geelong, Gladstone, Port Lincoln, Mackay, Melbourne, Newcastle, Portland, Sydney, Townsville, Wollongong

Iron ore

- Dampier

- Port Hedland

- Geraldton

- Oakajee - proposed 2006

- Esperance

- Port Lincoln - possible 2007

Tasmania

Merchant marine vessels

In 2006, the Australian fleet consisted of 53 ships of 1,000 gross tonnage or over. The use of foreign registered ships to carry Australian cargoes between Australian ports is permitted under a permit scheme, with either Single Voyage Permit (SVP) or a Continuous Voyage Permit (CVP) being issued to ships.[31] Between 1996 and 2002 the number of permits issued has increased by about 350 per cent.[32]

Over recent years the number of Australian registered and flagged ships has greatly declined, from 75 ships in 1996 to less than 40 in 2007, by 2009 the number is now approaching 30. Marine unions blame the decline on the shipping policy of the Howard Government which permitted foreign ships to carry coastal traffic.[33]

There have also been cases where locally operated ships have Australian flag from the vessel, registering it overseas under a flag of convenience, then hiring foreign crews who earn up to about half the monthly rate of Australian sailors.[32] Such moves were supported by the Howard Government but opposed by maritime unions and the Australian Council of Trade Unions.[34] The registration of the ships overseas also meant the earnings of the ships are not subject to Australian corporate taxation laws.[33]

Aviation

Qantas is the flag carrier of Australia. The Australian National Airways was the predominant domestic carrier from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s. After World War II, Qantas was nationalised and its domestic operations were transferred to Trans Australia Airlines in 1946. The Two Airlines Policy was formally established in 1952 to ensure the viability of both airlines. However, ANA's leadership was quickly eroded by TAA, and it was acquired by Ansett Airways in 1957. The duopoly continued for the next four decades. In the mid-1990s TAA was merged with Qantas and later privatised. Ansett collapsed in September 2001. In the following years, Virgin Australia became a challenger to Qantas. Both companies launched low-cost subsidiaries Jetstar and Tiger Airways Australia respectively.

Overseas flights from Australia to Europe via the Eastern Hemisphere are known as the Kangaroo Route, whereas flights via the Western Hemisphere are known as the Southern Cross Route. In 1954, the first flight from Australia to North America was completed, as a 60-passenger Qantas aircraft connected Sydney with San Francisco and Vancouver, having fuel stops at Fiji, Canton Island and Hawaii. In 1982, a Pan Am first flew non-stop from Los Angeles to Sydney. A non-stop flight between Australia and Europe was first completed in March 2018 from Perth to London.

There are many airports around Australia paved or unpaved. A 2004 estimate put the number of airports at 448. The busiest airports in Australia are:

- Sydney Airport Sydney, New South Wales SYD

- Melbourne Airport Melbourne, Victoria MEL

- Brisbane Airport Brisbane, Queensland BNE

- Perth Airport Perth, Western Australia PER

- Adelaide Airport Adelaide, South Australia ADL

- Gold Coast Airport Gold Coast, Queensland OOL

- Cairns Airport Cairns, Queensland CNS

- Canberra Airport Canberra, Australian Capital Territory CBR

- Hobart International Airport Hobart, Tasmania HBA

- Darwin International Airport, Northern Territory DRW

- Townsville Airport Townsville, Queensland TSV

Airports with paved runways

There are 305 airports with paved runways:

- Over 3,047 m (10,000 ft): 10

- 2,438 to 3,047 m (8,000 to 10,000 ft): 12

- 1,524 to 2,437 m (5,000 to 8,000 ft): 131

- 914 to 1,523 m (3,000 to 5,001 ft): 139

- Under 914 m (3,000 ft): 13 (2004 estimate)

Airports with unpaved runways

There are 143 airports with unpaved runways:

- 1,524 to 2,437 m (5,000 to 8,000 ft): 17

- 914 to 1,523 m (3,000 to 5,000 ft): 112

- Under 914 m (3,000 ft): 14 (2004 estimate)

Note:

sourced from CIA World Fact Book https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html

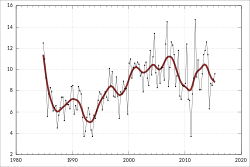

Environmental impact

The environmental impact of transport in Australia is considerable. In 2009, transport emissions made up 15.3% of Australia's total greenhouse gas emissions. Between 1990 and 2009, transport emissions grew by 34.6%, the second-highest growth rate in emissions after stationary energy.[35]

Australia subsidises fossil fuel energy, keeping prices artificially low and raising greenhouse gas emissions due to the increased use of fossil fuels as a result of the subsidies. The Australian Energy Regulator and state agencies such as the New South Wales' Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal set and regulate electricity prices, thereby lowering production and consumer cost.

See also

- Inland Railway

- Lonie Report

References

- "Transport in Australia". International Transport Statistics Database. iRAP. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- "Where are we now?". Australian Automobile Association. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- CIA world fact book.

- Urban Australia: Where most of us live. CSIRO. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- Schmidt, Bridie (30 August 2019). "First Tesla Model 3 electric sedans delivered to customers in Australia". RenewEconomy. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Charlwood, Sam (31 May 2019). "Tesla Model 3 Australian pricing revealed". Carsales. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Schmidt, Bridie (6 March 2020). "Tesla claims 80% of Australian market as electric vehicles near 18,000 mark". The Driven. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- Latimer, Cole (27 November 2018). "Electric cars continue push into Australia despite lack of government support". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Harris, Rob (5 February 2020). "Sharp jump in electric vehicle sales underscores 'untapped potential'". The Age. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (29 May 2020). "Media Release - Electric vehicle registrations almost double (Media Release)". www.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "New (MY19) Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV - Summer 2018" (PDF) (Press release). Mitsubishi Motors. 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018. See tables in pp. 3-4.

- "Tesla takes 70 per cent of market, as Australia electric car sales reach 5,000 in 2019". The Driven. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "Tesla Models X and 3 ranked among Australia's Top 3 safest cars for 2019". The Driven. 20 December 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Schmidt, Bridie (31 January 2020). "Mercedes Benz electric car beats Model 3 to win top Australia car award". The Driven. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "The State of Electric vehicles in Australia - Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA)". Australian Renewable Energy Agency. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Topsfield, Jewel (26 December 2019). "Victoria rolls out electric car charging stations to tackle 'range anxiety'". The Age. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Energy (17 December 2019). "Zero emissions vehicles". Energy. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Australia's SEA Electric takes massive order for 100 electric trucks". The Driven. 15 November 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Australia's SEA Electric is set to displace diesel in commercial vehicles worldwide". pv magazine Australia. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "NSW flags imminent release of EV strategy, as feds ignore electric in auto transition report". The Driven. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- editor, Katharine Murphy Political (26 February 2020). "Australia's electricity market must be 100% renewables by 2035 to achieve net zero by 2050 - study". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 February 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Light rail in Newcastle opening from Monday 18 February Transport for NSW 3 February 2019

- Start date revealed for Canberra’s light rail system The Canberra Times, 19 March 2019, Retrieved 28 April 2019

- includes modern tram networks

- includes public ferry and Water taxi services

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 April 2003. Retrieved 1 April 2003.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Sugarloaf Pipeline Project". Melbourne Water. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- "Wimmera Mallee Pipeline". GWMWater. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- "Melbourne to Geelong Pipeline". Barwon Water. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- Ian Mudie Riverboats Sun Books, Melbourne, Victoria 1965

- Australian Shipowners Association. "Industry Policy". asa.com.au. Archived from the original on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- Paul Robinson (26 March 2002). "Maritime unions slam use of 'cheap' foreign labour". The Age. theage.com.au. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- Martin Byrne (22 October 2009). "A new tanker ship for Australia" (PDF). Letter from the Australian Institute of Marine and Power Engineers to the Federal Minister. aimpe.asn.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- Liz Porter (14 July 2002). "Shipping out, and definitely not shaping up". The Age. theage.com.au. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- Australian Government Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (2010). Australian national greenhouse gas accounts (PDF) (Report).

Sources

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Transport in Australia. |