Monarchy of Tuvalu

The monarchy of Tuvalu is a system of government in which a hereditary monarch is the sovereign and head of state of Tuvalu. The present monarch of Tuvalu is Queen Elizabeth II,[1] who is also the Sovereign of 15 other Commonwealth realms.[2] The Queen's constitutional roles are mostly delegated to the Governor-General of Tuvalu.

| Queen of Tuvalu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Incumbent | |

| |

| Elizabeth II | |

| Details | |

| Style | Her Majesty |

| Heir apparent | Charles, Prince of Wales |

| First monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Formation | 1 October 1978 |

|

|---|

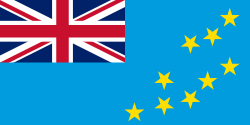

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Tuvalu |

|

|

|

|

The Head of State is recognised in section 50 of the Constitution of Tuvalu, as a symbol of the unity and identity of Tuvalu.[3] The powers of the head of state are set out in section 52 (1) of the Constitution.[4][5]

Part IV of the Constitution confirms the head of state of Tuvalu is Queen Elizabeth II as the sovereign of Tuvalu and provides for the rules for succession to the Crown. As set out in section 54 of the Constitution, the Queen’s representative is the governor-general. Section 58 of the Constitution requires the governor-general to perform the functions of the head of state when the sovereign is outside Tuvalu or otherwise incapacitated.[4][5] The governor-general of Tuvalu is appointed by the monarch upon the advice of the Prime Minister of Tuvalu.

Royal succession is governed by the English Act of Settlement of 1701, which is part of constitutional law.

International and domestic role

Fifty-two states are members of the Commonwealth of Nations. Sixteen of these countries are specifically Commonwealth realms who recognise, individually, the same person as their Monarch and Head of State; Tuvalu is one of these.[6] Despite sharing the same person as their respective national monarch, each of the Commonwealth realms—including Tuvalu—is sovereign and independent of the others.

Development of shared monarchy

The Balfour Declaration of 1926 provided the Dominions the right to be considered equal to Britain, rather than subordinate; an agreement that had the result of, in theory, a shared Crown that operates independently in each realm rather than a unitary British Crown under which all the dominions were secondary. The Monarchy thus ceased to be an exclusively British institution, although it has often been called "British" since this time (in both legal and common language) for reasons historical, legal, and of convenience. The Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act, 1927 was the first indication of this shift in law, further elaborated in the Statute of Westminster 1931.

Tuvalu achieved independence in 1978 but retained the Queen as Head of State. Under the Statute of Westminster, Tuvalu has a common monarchy with Britain and the other Commonwealth realms.

On all matters of the Tuvaluan State, the monarch is advised solely by Tuvaluan ministers.[7] 16 June remains a public holiday in Tuvalu as the Queen's Official Birthday.

The Queen of Tuvalu and the Duke of Edinburgh toured Tuvalu between 26–27 October 1982. The royal couple were carried around in ceremonial litters and later served with traditional local dishes on a banquet.[8][9] A sheet of commemorative stamps was issued for the royal visit by the Tuvalu Philatelic Bureau.

Title

By the Act 1 of 1987 of the Parliament of Tuvalu her style and title are: Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God, Queen of Tuvalu and of Her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth.[10]

This style communicates Tuvalu's status as an independent monarchy, highlighting the Monarch's role specifically as Queen of Tuvalu, as well as the shared aspect of the Crown throughout the Commonwealth. Typically, the Sovereign is styled "Queen of Tuvalu," and is addressed as such when in Tuvalu, or performing duties on behalf of Tuvalu abroad.

Constitutional role

The Monarchy of Tuvalu and the Governor General

The Monarchy of Tuvalu exists in a framework of a parliamentary representative democracy. As a constitutional monarch, The Queen acts entirely on the advice of her Government ministers in Tuvalu.[7] The Head of State is recognised in section 50 of the Constitution of Tuvalu, as a symbol of the unity and identity of Tuvalu. The powers of the Head of State are set out in section 52 (1) of the Constitution.[4][5]

Part IV of the Constitution confirms the Head of State of Tuvalu is Queen Elizabeth II as the Sovereign of Tuvalu and provides for the rules for succession to the Crown. As set out in section 54 of the Constitution, the Queen’s representative is the governor general. Section 58 of the Constitution requires the governor general to perform the functions of the Head of State when the Sovereign is outside Tuvalu or otherwise incapacitated.[4][5] The governor general of Tuvalu is appointed by the monarch upon the advice of the Prime Minister of Tuvalu.

In 1986 the Constitution adopted upon independence was amended in order to give attention to Tuvaluan custom and tradition as well as the aspirations and values of the Tuvaluan people.[11] The changes placed greater emphasis on Tuvaluan community values rather than Western concepts of individual entitlement.[12] The preamble was changed and an introductory ‘Principles of the Constitution’ was added.

The preamble to the Constitution of Tuvalu recites that the Ellice Islands, after coming under the protection of Queen Victoria in 1892, had, in January 1916, in conjunction with the Gilbert Islands, become known as the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony; and that after the Ellice Islands had been established by Queen Elizabeth as a separate colony in October 1975 under their ancient name of Tuvalu, a constitution had been adopted which was given the force of law by Order in Council, taking effect on 1 October 1978. The constitution now provides that Queen Elizabeth II is the sovereign of Tuvalu and the head of state and that references to the sovereign extend to the sovereign's heirs and successors.[4][5]

Duties

As a constitutional monarch, The Queen acts entirely on the advice of her government ministers in Tuvalu.[7]

Most of the Queen's domestic duties are performed by the governor-general. The governor-general represents the Queen on ceremonial occasions such as the opening of parliament, the presentation of honours and military parades. Under the constitution, the governor-general is given authority to act in some matters, for example in appointing and disciplining officers of the civil service, in proroguing Parliament. As in the other Commonwealth realms, however, the monarch's role, and thereby the governor-general's role, is almost entirely symbolic and cultural, acting as a symbol of the legal authority under which all governments operate, and the powers that are constitutionally hers are exercised almost wholly upon the advice of the Cabinet, made up of Ministers of the Crown. It has been said since the death of Queen Anne in 1714, the last monarch to head the British Cabinet, that the monarch "reigns" but does not "rule". In exceptional circumstances, however, the monarch or governor-general can act against such advice based upon his or her reserve powers.[13]

There are also a few duties which must be specifically performed by, or bills that require assent by the Queen. These include: signing the appointment papers of governors-general, the confirmation of awards of honours, and approving any change in her title.

It is also possible that if the governor-general decided to go against the prime minister's or the government's advice, the prime Minister could appeal directly to the monarch, or even recommend that the monarch dismiss the governor-general.

Succession

The constitution provides that the Queen's heirs shall succeed her as head of state. Unlike some realms, but as with others, Tuvalu defers to United Kingdom law to determine the line of succession to the Tuvaluan throne.[14] As such, succession is by absolute primogeniture and governed by the Act of Settlement 1701, the Bill of Rights 1689, and the Succession to the Crown Act 2013. This legislation lays out the rules that the monarch cannot be a Roman Catholic and must be in communion with the Church of England upon ascending the throne. The heir apparent is Elizabeth II's eldest son, Charles, who has no official title outside of the UK, but is accorded his UK title, Prince of Wales, as a courtesy title.

Legal role

All laws in Tuvalu are enacted with the sovereign's, or the governor-general's granting of Royal Assent; it and proclamation are required for all acts of parliament, usually granted or withheld by the governor-general.[13] The governor-general may reserve a bill for the monarch's pleasure, that is to say, allow the monarch to make a personal decision on the bill. The monarch has the power to disallow a bill (within a time limit specified by the constitution).

The sovereign is deemed the "fount of justice," and is responsible for rendering justice for all subjects. The sovereign does not personally rule in judicial cases; instead, judicial functions are performed in his or her name. The common law holds that the sovereign "can do no wrong"; the monarch cannot be prosecuted in his or her own courts for criminal offences. Civil lawsuits against the Crown in its public capacity (that is, lawsuits against the government) are permitted; however, lawsuits against the monarch personally are not cognizable.

The sovereign, and by extension the governor-general, also exercises the "prerogative of mercy," and may pardon offences against the Crown. Pardons may be awarded before, during, or after a trial. The exercise of the 'Power of Mercy' to grant a pardon and the commutation of prison sentences in described in section 80 of the Constitution.

In Tuvalu the legal personality of the state is referred to as Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Tuvalu. For example, if a lawsuit is filed against the government, the respondent is formally described as Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Tuvalu. The monarch as an individual takes no more role in such an affair than in any other business of government.

Referendum of 2008

In the first years of the 21st century there was a debate about the abolition of the monarchy. Prime Minister Saufatu Sopoanga had stated in 2004 that he was in favour of replacing the Queen as Tuvalu's head of state, a view supported by popular former Prime Minister Ionatana Ionatana; Sopoanga also stated that public opinion would be evaluated first before taking any further moves.[15] Former Prime Minister Kamuta Latasi also supported the idea.

A referendum was held in Tuvalu in 2008, giving voters the option of retaining the monarchy, or abolishing it in favour of a republic. The monarchy was retained with 1,260 votes to 679 (64.98%).[16][17] Turnout was low, with about 2,000 voters of a potential 9,000 taking part.

References

- Government

- The Monarchy Today > Queen and Commonwealth

- "Amasone v Attorney General [2003] TVHC 4; Case No 24 of 2003 (6 August 2003)". PACLII. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- "The Constitution of Tuvalu". PACLII. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- "The Constitution of Tuvalu". Tuvalu Islands. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- The Monarchy Today > Queen and Commonwealth > Members

- "The Queen's Role in Tuvalu". Official website of the British Monarchy. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "Slide show of Queen Elizabeth II & the Duke of Edinburgh during their visit to Tuvalu in October, 1982". YouTube (video). Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "'Change in Tuvalu' - Royal Visit to Tuvalu by Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II & The Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Philip in October, 1982". YouTube (video). Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "The Queen and Tuvalu (style and title)". Official website of the British Monarchy. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Farran, Sue (2006). "Obstacle to Human Rights? Considerations from the South Pacific" (PDF). Journal of Legal Pluralism: 77–105.

- Levine, Stephen (1992). "Constitutional change in Tuvalu". Australian Journal of Political Science. 27 (3): 492–509.

- "Amasone v Attorney General [2003] TVHC 4; Case No 24 of 2003 (6 August 2003)". PACLII. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- Clegg, Nick (26 March 2015), Commencement of Succession to the Crown Act 2013 :Written statement - HCWS490, London: Queen's Printer, retrieved 26 March 2015

- Chapman, Paul (6 May 2004). "Tuvalu may ditch the Queen and declare a republic". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 30 June 2006.

- "Tuvalu votes to maintain monarchy", Radio Australia, 17 June 2008

- "Tuvaluans vote against republic, Tuvalu News, 30 April 2008