Permian

The Permian (/ˈpɜːr.mi.ən/ PUR-mee-ən)[2] is a geologic period and system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous period 298.9 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic period 251.902 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleozoic era; the following Triassic period belongs to the Mesozoic era. The concept of the Permian was introduced in 1841 by geologist Sir Roderick Murchison, who named it after the region of Perm in Russia.[3][4][5][6]

| Permian Period 298.9–251.902 million years ago | |

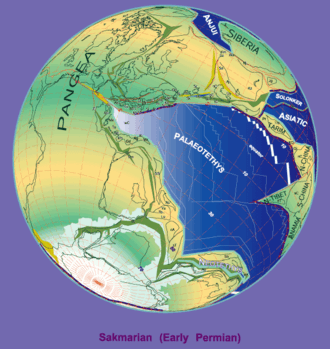

A map of the world as it appeared during the Late Permian, just before the end-Capitanian mass extinction event. (260 ma) | |

| Mean atmospheric O 2 content over period duration |

c. 23 vol % (115 % of modern level) |

| Mean atmospheric CO 2 content over period duration |

c. 900 ppm (3 times pre-industrial level) |

| Mean surface temperature over period duration | c. 16 °C (2 °C above modern level) |

| Sea level (above present day) | Relatively constant at 60 m (200 ft) in early Permian; plummeting during the middle Permian to a constant −20 m (−66 ft) in the late Permian.[1] |

Key events in the Permian -300 — – -295 — – -290 — – -285 — – -280 — – -275 — – -270 — – -265 — – -260 — – -255 — – -250 — An approximate timescale of key Permian events. Axis scale: millions of years ago. | |

The Permian witnessed the diversification of the early amniotes into the ancestral groups of the mammals, turtles, lepidosaurs, and archosaurs. The world at the time was dominated by two continents known as Pangaea and Siberia, surrounded by a global ocean called Panthalassa. The Carboniferous rainforest collapse left behind vast regions of desert within the continental interior.[7] Amniotes, which could better cope with these drier conditions, rose to dominance in place of their amphibian ancestors.

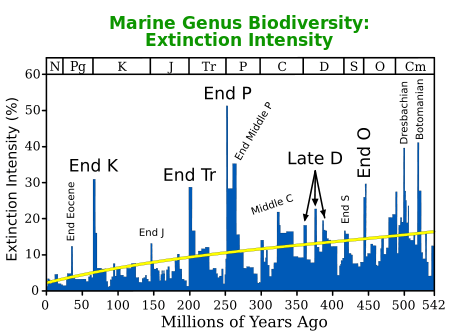

The Permian (along with the Paleozoic) ended with the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the largest mass extinction in Earth's history, in which nearly 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial species died out.[8] It would take well into the Triassic for life to recover from this catastrophe;[9] on land, ecosystems took 30 million years to recover.[10]

Discovery

The term "Permian" was introduced into geology in 1841 by Sir R. I. Murchison, president of the Geological Society of London, who identified typical strata in extensive Russian explorations undertaken with Édouard de Verneuil.[11][12] The region now lies in the Perm Krai of Russia.

ICS subdivisions

Official ICS 2018 subdivisions of the Permian System from most recent to most ancient rock layers are:[13]

- Lopingian epoch [259.1 ± 0.5 Mya – 251.902 ± 0.024 Mya]

- Changhsingian (Changxingian) [254.14 ± 0.07 Mya – 251.902 ± 0.024 Mya]

- Wuchiapingian (Wujiapingian) [259.1 ± 0.5 Mya – 254.14 ± 0.07 Mya]

- Others:

- Waiitian (New Zealand) [260.4 ± 0.7 Mya – 253.8 ± 0.7 Mya]

- Makabewan (New Zealand) [253.8 – 251.0 ± 0.4 Mya]

- Ochoan (North American) [260.4 ± 0.7 Mya – 251.0 ± 0.4 Mya]

- Guadalupian epoch [272.95 ± 0.11 – 259.1 ± 0.5 Mya]

- Capitanian stage [265.1 ± 0.4 – 259.1 ± 0.5 Mya]

- Wordian stage [268.8 ± 0.5 – 265.1 ± 0.4 Mya]

- Roadian stage [272.95 ± 0.11 – 268.8 ± 0.5 Mya]

- Others:

- Kazanian or Maokovian (European) [270.6 ± 0.7 – 260.4 ± 0.7 Mya][14]

- Braxtonian stage (New Zealand) [270.6 ± 0.7 – 260.4 ± 0.7 Mya]

- Cisuralian epoch [298.9 ± 0.15 – 272.95 ± 0.11 Mya]

- Kungurian stage [283.5 ± 0.6 – 272.95 ± 0.11 Mya]

- Artinskian stage [290.1 ± 0.26 – 283.5 ± 0.7 Mya]

- Sakmarian stage [293.52 ± 0.17 – 290.1 ± 0.26 Mya]

- Asselian stage [298.9 ± 0.15 – 293.52 ± 0.17 Mya]

- Others:

- Telfordian (New Zealand) [289 – 278]

- Mangapirian (New Zealand) [278 – 270.6]

Oceans

Sea levels in the Permian remained generally low, and near-shore environments were reduced as almost all major landmasses collected into a single continent—Pangaea. This could have in part caused the widespread extinctions of marine species at the end of the period by severely reducing shallow coastal areas preferred by many marine organisms.

Paleogeography

During the Permian, all the Earth's major landmasses were collected into a single supercontinent known as Pangaea. Pangaea straddled the equator and extended toward the poles, with a corresponding effect on ocean currents in the single great ocean ("Panthalassa", the "universal sea"), and the Paleo-Tethys Ocean, a large ocean that existed between Asia and Gondwana. The Cimmeria continent rifted away from Gondwana and drifted north to Laurasia, causing the Paleo-Tethys Ocean to shrink. A new ocean was growing on its southern end, the Tethys Ocean, an ocean that would dominate much of the Mesozoic era. Large continental landmass interiors experience climates with extreme variations of heat and cold ("continental climate") and monsoon conditions with highly seasonal rainfall patterns. Deserts seem to have been widespread on Pangaea. Such dry conditions favored gymnosperms, plants with seeds enclosed in a protective cover, over plants such as ferns that disperse spores in a wetter environment. The first modern trees (conifers, ginkgos and cycads) appeared in the Permian.

Three general areas are especially noted for their extensive Permian deposits—the Ural Mountains (where Perm itself is located), China, and the southwest of North America, including the Texas red beds. The Permian Basin in the U.S. states of Texas and New Mexico is so named because it has one of the thickest deposits of Permian rocks in the world.

Climate

The climate in the Permian was quite varied. At the start of the Permian, the Earth was still in an ice age, which began in the Carboniferous. Glaciers receded around the mid-Permian period as the climate gradually warmed, drying the continent's interiors.[15] In the late Permian period, the drying continued although the temperature cycled between warm and cool cycles.[15]

Life

Marine biota

Permian marine deposits are rich in fossil mollusks, echinoderms, and brachiopods.[16] Fossilized shells of two kinds of invertebrates are widely used to identify Permian strata and correlate them between sites: fusulinids, a kind of shelled amoeba-like protist that is one of the foraminiferans, and ammonoids, shelled cephalopods that are distant relatives of the modern nautilus. By the close of the Permian, trilobites and a host of other marine groups became extinct.

Terrestrial biota

Terrestrial life in the Permian included diverse plants, fungi, arthropods, and various types of tetrapods. The period saw a massive desert covering the interior of Pangaea. The warm zone spread in the northern hemisphere, where extensive dry desert appeared.[16] The rocks formed at that time were stained red by iron oxides, the result of intense heating by the sun of a surface devoid of vegetation cover. A number of older types of plants and animals died out or became marginal elements.

The Permian began with the Carboniferous flora still flourishing. About the middle of the Permian a major transition in vegetation began. The swamp-loving lycopod trees of the Carboniferous, such as Lepidodendron and Sigillaria, were progressively replaced in the continental interior by the more advanced seed ferns and early conifers. At the close of the Permian, lycopod and equisete swamps reminiscent of Carboniferous flora survived only on a series of equatorial islands in the Paleo-Tethys Ocean that later would become South China.[17]

The Permian saw the radiation of many important conifer groups, including the ancestors of many present-day families. Rich forests were present in many areas, with a diverse mix of plant groups. The southern continent saw extensive seed fern forests of the Glossopteris flora. Oxygen levels were probably high there. The ginkgos and cycads also appeared during this period.

Insects

From the Pennsylvanian subperiod of the Carboniferous period until well into the Permian, the most successful insects were primitive relatives of cockroaches. Six fast legs, four well-developed folding wings, fairly good eyes, long, well-developed antennae (olfactory), an omnivorous digestive system, a receptacle for storing sperm, a chitin-based exoskeleton that could support and protect, as well as a form of gizzard and efficient mouth parts, gave it formidable advantages over other herbivorous animals. About 90% of insects at the start of the Permian were cockroach-like insects ("Blattopterans").[18]

Primitive forms of dragonflies (Odonata) were the dominant aerial predators and probably dominated terrestrial insect predation as well. True Odonata appeared in the Permian,[19][20] and all are effectively semi-aquatic insects (aquatic immature stages, and terrestrial adults), as are all modern odonates. Their prototypes are the oldest winged fossils,[21] dating back to the Devonian, and are different in several respects from the wings of other insects.[22] Fossils suggest they may have possessed many modern attributes even by the late Carboniferous, and it is possible that they captured small vertebrates, for at least one species had a wing span of 71 cm (28 in).[23] Several other insect groups appeared or flourished during the Permian, including the Coleoptera (beetles) and Hemiptera (true bugs).

Tetrapods

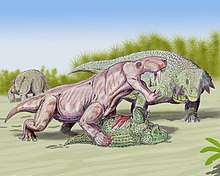

Early Permian terrestrial faunas were dominated by pelycosaurs, diadectids and amphibians,[24][25] the middle Permian by primitive therapsids such as the dinocephalia, and the late Permian by more advanced therapsids such as gorgonopsians and dicynodonts. Towards the very end of the Permian the first archosauriforms appeared, a group that would give rise to the pseudosuchians, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs in the following period. Also appearing at the end of the Permian were the first cynodonts, which would go on to evolve into mammals during the Triassic. Another group of therapsids, the therocephalians (such as Lycosuchus), arose in the Middle Permian.[26][27] There were no flying vertebrates (though there was a family of gliding reptiles known as weigeltisaurs).

The Permian period saw the development of a fully terrestrial fauna and the appearance of the first large herbivores and carnivores. It was the high tide of the anapsids in the form of the massive pareiasaurs and host of smaller, generally lizard-like groups. A group of small reptiles, the diapsids, started to abound. These were the ancestors to most modern reptiles and the ruling dinosaurs as well as pterosaurs and crocodiles.

Synapsids (the group that would later include mammals) thrived and diversified greatly at this time. Permian synapsids included some large members such as Dimetrodon. The special adaptations of synapsids enabled them to flourish in the drier climate of the Permian and they grew to dominate the vertebrates.[24]

Permian stem-amniotes consisted of temnospondyli, lepospondyli and batrachosaurs.

Edaphosaurus pogonias and Platyhystrix – Early Permian, North America and Europe

Edaphosaurus pogonias and Platyhystrix – Early Permian, North America and Europe Dimetrodon grandis and Eryops – Early Permian, North America

Dimetrodon grandis and Eryops – Early Permian, North America Ocher fauna, Estemmenosuchus uralensis and Eotitanosuchus – Middle Permian, Ural Region

Ocher fauna, Estemmenosuchus uralensis and Eotitanosuchus – Middle Permian, Ural Region Titanophoneus and Ulemosaurus – Ural Region

Titanophoneus and Ulemosaurus – Ural Region Inostrancevia alexandri and Scutosaurus – Late Permian, North European Russia (Northern Dvina)

Inostrancevia alexandri and Scutosaurus – Late Permian, North European Russia (Northern Dvina)

Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian ended with the most extensive extinction event recorded in paleontology: the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Ninety to 95% of marine species became extinct, as well as 70% of all land organisms. It is also the only known mass extinction of insects.[9][28] Recovery from the Permian–Triassic extinction event was protracted; on land, ecosystems took 30 million years to recover.[10] Trilobites, which had thrived since Cambrian times, finally became extinct before the end of the Permian. Nautiloids, a subclass of cephalopods, surprisingly survived this occurrence.

There is evidence that magma, in the form of flood basalt, poured onto the Earth's surface in what is now called the Siberian Traps, for thousands of years, contributing to the environmental stress that led to mass extinction. The reduced coastal habitat and highly increased aridity probably also contributed. Based on the amount of lava estimated to have been produced during this period, the worst-case scenario is the release of enough carbon dioxide from the eruptions to raise world temperatures five degrees Celsius.[15]

Another hypothesis involves ocean venting of hydrogen sulfide gas. Portions of the deep ocean will periodically lose all of its dissolved oxygen allowing bacteria that live without oxygen to flourish and produce hydrogen sulfide gas. If enough hydrogen sulfide accumulates in an anoxic zone, the gas can rise into the atmosphere. Oxidizing gases in the atmosphere would destroy the toxic gas, but the hydrogen sulfide would soon consume all of the atmospheric gas available. Hydrogen sulfide levels might have increased dramatically over a few hundred years. Models of such an event indicate that the gas would destroy ozone in the upper atmosphere allowing ultraviolet radiation to kill off species that had survived the toxic gas.[29] There are species that can metabolize hydrogen sulfide.

Another hypothesis builds on the flood basalt eruption theory. An increase in temperature of five degrees Celsius would not be enough to explain the death of 95% of life. But such warming could slowly raise ocean temperatures until frozen methane reservoirs below the ocean floor near coastlines melted, expelling enough methane (among the most potent greenhouse gases) into the atmosphere to raise world temperatures an additional five degrees Celsius. The frozen methane hypothesis helps explain the increase in carbon-12 levels found midway in the Permian–Triassic boundary layer. It also helps explain why the first phase of the layer's extinctions was land-based, the second was marine-based (and starting right after the increase in C-12 levels), and the third land-based again.[30]

An even more speculative hypothesis is that intense radiation from a nearby supernova was responsible for the extinctions.[31]

It has been hypothesised that huge meteorite impact crater (Wilkes Land crater) with a diameter of around 500 kilometers in Antarctica represents an impact event that may be related to the extinction.[32] The crater is located at a depth of 1.6 kilometers beneath the ice of Wilkes Land in eastern Antarctica. Scientists speculate that this impact may have caused the Permian–Triassic extinction event, although its age is bracketed only between 100 million and 500 million years ago. They also speculate that it may have contributed in some way to the separation of Australia from the Antarctic landmass, which were both part of a supercontinent called Gondwana. Levels of iridium and quartz fracturing in the Permian–Triassic layer do not approach those of the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary layer. Given that a far greater proportion of species and individual organisms became extinct during the former, doubt is cast on the significance of a meteorite impact in creating the latter. Further doubt has been cast on this theory based on fossils in Greenland that show the extinction to have been gradual, lasting about eighty thousand years, with three distinct phases.[33]

Many scientists argue that the Permian–Triassic extinction event was caused by a combination of some or all of the hypotheses above and other factors; the formation of Pangaea decreased the number of coastal habitats and may have contributed to the extinction of many clades.

See also

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- Olson's Extinction

- List of Permian tetrapods

References

- Haq, B. U.; Schutter, SR (2008). "A Chronology of Paleozoic Sea-Level Changes". Science. 322 (5898): 64–68. Bibcode:2008Sci...322...64H. doi:10.1126/science.1161648. PMID 18832639.

- "Permian". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- Olroyd, D.R. (2005). "Famous Geologists: Murchison". In Selley, R.C.; Cocks, L.R.M.; Plimer, I.R. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Geology, volume 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 213. ISBN 0-12-636380-3.

- Ogg, J.G.; Ogg, G.; Gradstein, F.M. (2016). A Concise Geologic Time Scale: 2016. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-444-63771-0.

- Murchison, R.I.; de Verneuil, E.; von Keyserling, A. (1842). On the Geological Structure of the Central and Southern Regions of Russia in Europe, and of the Ural Mountains. London: Richard and John E. Taylor. p. 14.

Permian System. (Zechstein of Germany — Magnesian limestone of England)—Some introductory remarks explain why the authors have ventured to use a new name in reference to a group of rocks which, as a whole, they consider to be on the parallel of the Zechstein of Germany and the magnesian limestone of England. They do so, not merely because a portion of deposits has long been known by the name "grits of Perm," but because, being enormously developed in the governments of Perm and Orenburg, they there assume a great variety of lithological features ...

- Murchison, R.I.; de Verneuil, E.; von Keyserling, A. (1845). Geology of Russia in Europe and the Ural Mountains. Vol. 1: Geology. London: John Murray. pp. 138–139.

...Convincing ourselves in the field, that these strata were so distinguished as to constitute a system, connected with the carboniferous rocks on the one hand, and independent of the Trias on the other, we ventured to designate them by a geographical term, derived from the ancient kingdom of Permia, within and around whose precincts the necessary evidences had been obtained. ... For these reasons, then, we were led to abandon both the German and British nomenclature, and to prefer a geographical name, taken from the region in which the beds are loaded with fossils of an independent and intermediary character; and where the order of superposition is clear, the lower strata of the group being seen to rest upon the Carboniferous rocks.

- Sahney, S., Benton, M.J. & Falcon-Lang, H.J. (2010). "Rainforest collapse triggered Pennsylvanian tetrapod diversification in Euramerica". Geology. 38 (12): 1079–1082. Bibcode:2010Geo....38.1079S. doi:10.1130/G31182.1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "{title}". Archived from the original on 2015-04-14. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- "GeoKansas--Geotopics--Mass Extinctions". ku.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- Sahney, S.; Benton, M. J. (2008). "Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1636): 759–65. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1370. PMC 2596898. PMID 18198148.

- Benton, M.J. et al., Murchison’s first sighting of the Permian, at Vyazniki in 1841 Archived 2012-03-24 at WebCite, Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, accessed 2012-02-21

- Murchison, Roderick Impey (1841) "First sketch of some of the principal results of a second geological survey of Russia," Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, series 3, 19 : 417-422. From p. 419: "The carboniferous system is surmounted, to the east of the Volga, by a vast series of marls, schists, limestones, sandstones and conglomerates, to which I propose to give the name of "Permian System," … ."

- "International Stratigraphic Chart v2018/08" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "GeoWhen Database - Kazanian". www.stratigraphy.org.

- Palaeos: Life Through Deep Time > The Permian Period Archived 2013-06-29 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 1 April 2013.

- "The Permian Period". berkeley.edu.

- Xu, R. & Wang, X.-Q. (1982): Di zhi shi qi Zhongguo ge zhu yao Diqu zhi wu jing guan (Reconstructions of Landscapes in Principal Regions of China). Ke xue chu ban she, Beijing. 55 pages, 25 plates.

- Zimmerman EC (1948) Insects of Hawaii, Vol. II. Univ. Hawaii Press

- Grzimek HC Bernhard (1975) Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia Vol 22 Insects. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co. NY.

- Riek EF Kukalova-Peck J (1984) "A new interpretation of dragonfly wing venation based on early Upper Carboniferous fossils from Argentina (Insecta: Odonatoida and basic character states in Pterygote wings.)" Can. J. Zool. 62; 1150-1160.

- Wakeling JM Ellington CP (1997) Dragonfly flight III lift and power requirements" Journal of Experimental Biology 200; 583-600, on p589

- Matsuda R (1970) Morphology and evolution of the insect thorax. Mem. Ent. Soc. Can. 76; 1-431.

- Riek EF Kukalova-Peck J (1984) A new interpretation of dragonfly wing venation based on early Upper Carboniferous fossils from Argentina (Insecta: Odonatoida and basic character states in Pterygote wings.) Can. J. Zool. 62; 1150-1160

- Huttenlocker, A. K., and E. Rega. 2012. The Paleobiology and Bone Microstructure of Pelycosaurian-grade Synapsids. Pp. 90–119 in A. Chinsamy (ed.) Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation, Histology, Biology. Indiana University Press.

- "NAPC Abstracts, Sto - Tw". berkeley.edu.

- Huttenlocker A. K. (2009). "An investigation into the cladistic relationships and monophyly of therocephalian therapsids (Amniota: Synapsida)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 157 (4): 865–891. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00538.x.

- Huttenlocker A. K.; Sidor C. A.; Smith R. M. H. (2011). "A new specimen of Promoschorhynchus (Therapsida: Therocephalia: Akidnognathidae) from the lowermost Triassic of South Africa and its implications for therocephalian survival across the Permo-Triassic boundary". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31: 405–421. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.546720.

- Andrew Alden. "The Great Permian-Triassic Extinction". About.com Education.

- Kump, L.R., A. Pavlov, and M.A. Arthur (2005). "Massive release of hydrogen sulfide to the surface ocean and atmosphere during intervals of oceanic anoxia". Geology. 33 (May): 397–400. Bibcode:2005Geo....33..397K. doi:10.1130/G21295.1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Benton, Michael J.; Twitchett, Richard J. (7 July 2003). "How to kill (almost) all life: the end-Permian extinction event". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 18 (7): 358–365. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00093-4.

- Ellis, J (January 1995). "Could a nearby supernova explosion have caused a mass extinction?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 92 (1): 235–8. arXiv:hep-ph/9303206. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92..235E. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.1.235. PMC 42852. PMID 11607506.

- Gorder, Pam Frost (June 1, 2006). "Big Bang in Antarctica – Killer Crater Found Under Ice". Ohio State University Research News. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016.

- Shen S.-Z.; et al. (2011). "Calibrating the End-Permian Mass Extinction". Science. 334 (6061): 1367–72. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1367S. doi:10.1126/science.1213454. PMID 22096103.

Further reading

- Ogg, Jim (June 2004). "Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's)". stratigraphy.org. Archived from the original on 2004-02-19. Retrieved April 30, 2006.

External links

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Paleozoic#Permian |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Permian. |

- University of California offers a more modern Permian stratigraphy

- Classic Permian strata in the Glass Mountains of the Permian Basin

- "International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS)". Geologic Time Scale 2004. Retrieved September 19, 2005.

- Examples of Permian Fossils

- Permian (chronostratigraphy scale)

- Schneebeli-Hermann, Elke (2012), "Extinguishing a Permian World", Geology, 40 (3): 287–288, Bibcode:2012Geo....40..287S, doi:10.1130/focus032012.1