Monarchy of Barbados

The monarch of Barbados is the sovereign and head of state of Barbados. The current Barbadian monarch and head of state, since the independence of Barbados on 30 November 1966, is Queen Elizabeth II. As the sovereign, she is the personal embodiment of the Barbadian Crown. Although the person of the sovereign is equally shared with 15 other independent countries within the Commonwealth of Nations, each country's monarchy is separate and legally distinct. As a result, the current monarch is officially titled Queen of Barbados and, in this capacity, she, her husband, and other members of the Royal Family undertake public and private functions domestically and abroad as representatives of the Barbadian state. However, the Queen is the only member of the Royal Family with any constitutional role. The Queen lives predominantly in the United Kingdom and, while several powers are the sovereign's alone, most of the royal governmental and ceremonial duties in Barbados are carried out by the Queen's representative, the governor-general.

| Queen of Barbados | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Incumbent | |

| |

| Elizabeth II | |

| Details | |

| Style | Her Majesty |

| Heir apparent | Charles, Prince of Wales |

| First monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Formation | 30 November 1966 |

.svg.png) |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Barbados |

|

|

|

|

|

Administrative divisions |

|

Some of the powers of the Crown are exercisable by the monarch (such as appointing governors-general) and others by the governor-general (such as calling parliamentary elections). Further, the royal sign-manual is required for letters patent and orders in council. But, the authority for these acts stems from the Barbadian populace and, within the conventional stipulations of constitutional monarchy, the sovereign's direct participation in any of these areas of governance is limited, with most related powers entrusted for exercise (via advice or direction to the monarch or the viceroy) by the elected and appointed parliamentarians, the ministers of the Crown generally drawn from amongst them, and the judges and justices of the peace. The Crown today primarily functions as a guarantor of continuous and stable governance and a nonpartisan safeguard against the abuse of power.

The historical roots of the Barbadian monarchy date back to approximately the early 17th century, when King James VI of Scotland and I of England made the first claims to Barbados. Monarchical governance thenceforth evolved under a continuous succession of British sovereigns and eventually the Barbadian monarchy of today.

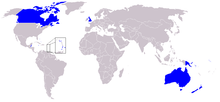

International and domestic aspects

The person who is the Barbadian sovereign is equally shared with 15 other monarchies (a grouping, including Barbados, known informally as the Commonwealth realms) in the 52-member Commonwealth of Nations, with the monarch residing predominantly in the oldest and most populous realm, the United Kingdom, and a viceroy—the Governor-General of Barbados—acting as the sovereign's representative in Barbados. This arrangement emerged among the older realms after the end of the First World War and is governed by the Statute of Westminster 1931. Since then, the pan-national Crown has had both a shared and a separate character and the sovereign's role as monarch of Barbados has been, since Barbados' independence in 1966, distinct to his or her position as monarch of any other realm, including the United Kingdom.[n 1][2] Only Barbadian ministers of the Crown may advise the sovereign on matters of the Barbadian state.[2] The monarchy thus ceased to be an exclusively British institution and in Barbados became a Barbadian, or "domesticated",[3] establishment.

This division is illustrated in a number of ways: The sovereign, for example, holds a unique Barbadian title and, when she is acting in public specifically as a representative of Barbados, she will use, where possible, Barbadian symbols, including the country's national flag, unique royal symbols, and the like. The sovereign similarly only draws from Barbadian coffers for support in the performance of her duties when in Barbados or acting as Queen of Barbados abroad; Barbadians do not pay any money to the Queen, either towards personal income or to support royal residences outside of Barbados. This applies equally to other members of the Royal Family. Normally, tax dollars pay only for the costs associated with the governor-general in the exercise of the powers of the Crown, including travel, security, residences, offices, and ceremonies.

A claim made by supporters of the monarchy is that it "keeps the line of stability open";[4] the sovereign's usual location outside the country means legitimate executive power would be unaffected by any hostile invasion of Barbados or other event that rendered the entire sitting government incapacitated or unable to function.[5] Such a situation has not arisen; however, it may have helped if the Operation Red Dog-invasion plot, which targeted the Commonwealth of Dominica and likely Barbados,[6] was not halted.[n 2]

Succession

By convention, succession in Barbados is deferred to the laws of the United Kingdom; whoever is monarch of the UK is automatically also monarch of Barbados. Succession in Britain is, for those born before 28 October 2011, by male-preference primogeniture and, for people born after 28 October 2011, by absolute primogeniture, governed by common law, the Act of Settlement 1701, Bill of Rights 1689, and Succession to the Crown Act 2013. This legislation limits the succession to the natural (i.e. non-adopted), legitimate descendants of Sophia, Electress of Hanover, and stipulates that the monarch cannot be a Roman Catholic and must be in communion with the Church of England upon ascending the throne. Though these laws still lie within the control of the British parliament, the United Kingdom agreed, via adopting the Statute of Westminster, not to change the rules of succession without the unanimous consent of the other realms, unless explicitly leaving the shared monarchy relationship.[7] This situation that applies symmetrically in all the other realms and has been likened to a treaty among these countries.[n 3] Barbados last indicated its consent to alteration to the line of succession in 2015, when the Governor-General-in-Council brought into force the Succession to the Throne Act, 2013, which signified the legislature's acquiescence to the British Succession to the Crown Bill 2013.[9]

Upon a demise of the Crown (the death or abdication of a sovereign), the late sovereign's heir immediately and automatically succeeds, without any need for confirmation or further ceremony; hence arises the phrase "The King is dead. Long live the King!" Following an appropriate period of mourning, the monarch is also crowned in the United Kingdom, though this ritual is not necessary for a sovereign to reign; for example, Edward VIII was never crowned, yet was undoubtedly king during his short time on the throne. All incumbent viceroys, judges, civil servants, legislators, military officers, etc., are not affected by the death of the monarch. After an individual ascends the throne, he or she typically continues to reign until death. Monarchs are not allowed to unilaterally abdicate; the only monarch to abdicate, Edward VIII, did so before Barbados was independent and, even then, only with the authorization of the governments of the United Kingdom and the then Dominions and special Acts of Parliament in each, as well as the UK.

Personification of the state

Today the sovereign is regarded as the personification, or legal personality, of the Barbadian state. Therefore, the state is referred to as Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Barbados; the state is referred to as such, or simply Regina, if a lawsuit is filed against the government. The monarch, in his or her position as sovereign, and not as an individual, is thus the owner of all state lands (called Crown land), buildings and equipment (called Crown held property), state-owned companies (called statutory bodies or Crown Corporations), and the copyright for all government publications (called Crown copyright), as well as guardianship of foster children (called Crown wards). Government staff (the Civil Service) are also employed by the monarch, as are the governor-general, judges, members of the Barbados Defence Force, police officers, and parliamentarians. Hence, many employees of the Crown are required by law to recite an oath of allegiance to the monarch before taking their posts, in reciprocation to the sovereign's Coronation Oath, wherein he or she promises "to govern the Peoples of... [Barbados]... according to their respective laws and customs".[10] The oath required by the Director of Public Prosecutions, for example, is: "I, [name], do swear that I will well and truly serve Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Her Heirs and Successors, in the office of Director of Public Prosecutions. So help me God", while that for judges is: "I, [name], do swear that I will well and truly serve Our Sovereign Lady Queen Elizabeth II, Her Heirs and Successors, in the office of Chief Justice/Judge of the Supreme Court and I will do right to all manner of people after the laws and usages of Barbados without fear or favour, affection or ill will. so help me God."[11]

Constitutional role

Barbados' constitution gives the country a similar parliamentary system of government to the other Commonwealth realms, wherein the role of the monarch and governor-general is both legal and practical, but not political. The Crown is regarded as a corporation, in which several parts share the authority of the whole, with the sovereign as the person at the centre of the constitutional construct,[12] meaning all powers of state are constitutionally reposed in the monarch. The constitution requires most of the Queen's domestic duties to be performed by the governor-general, appointed by the monarch on the advice of the Prime Minister of Barbados.[13]

All institutions of government are said to act under the sovereign's authority; the vast powers that belong to the Crown are collectively known as the Royal Prerogative. Parliamentary approval is not required for the exercise of the Royal Prerogative; moreover, the consent of the Crown must be obtained before either of the houses of parliament may even debate a bill affecting the sovereign's prerogatives or interests. While the Royal Prerogative is extensive, it is not unlimited; for example, the monarch does not have the prerogative to impose and collect new taxes—such an action requires the authorization of an Act of Parliament. The government of Barbados is also thus formally referred to as Her Majesty's Government. Further, the constitution instructs that any change to the position of the monarch, or the monarch's representative in Barbados, requires the consent of two-thirds of the all the members of each house of parliament.

Executive (Queen-in-Council)

One of the main duties of the Crown is to appoint a prime minister, who thereafter heads the Cabinet and advises the monarch or governor-general on how to execute their executive powers over all aspects of government operations and foreign affairs. Though the monarch's power is still a part of the executive process—the operation of the Cabinet is technically known as the Queen-in-Council (or Governor-in-Council)—the advice tendered is typically binding; the requirement of the governor-general to follow ministerial (either generally or specifically the prime minister's) advice is constitutionally enshrined in Barbados,[14] unlike in other Commonwealth realms, where it is a matter of convention.. Since the death of Queen Anne in 1714, the last monarch to head the British Cabinet, the monarch reigns but does not rule. This means that the monarch's, and thereby the viceroy's, role is almost entirely symbolic and cultural, acting as a symbol of the legal authority under which all governments and agencies operate, while the Cabinet directs the use of the Royal Prerogative, which includes the privilege to declare war, maintain the Queen's peace, and direct the actions of the Barbados Defence Force, as well as to summon and prorogue parliament and call elections. However, it is important to note that the Royal Prerogative belongs to the Crown and not to any of the ministers, though it may sometimes appear that way,[12] and the constitution allows the governor-general to unilaterally use these powers in relation to the dismissal of a prime minister, dissolution of parliament, and removal of a judge in exceptional, constitutional crisis situations.[15] There are also a few duties which must be specifically performed by, or bills that require assent by, the Queen. These include appointing the governor-general,[13] the creation of Barbadian honours, and the approval of any change in her Barbadian title.

The governor-general, to maintain the stability of government, must appoint as prime minister the individual most likely to maintain the support of the House of Assembly;[16] usually this is the leader of the political party with a majority in that house, but also, when no party or coalition holds a majority (referred to as a minority government situation), or other scenarios in which the governor-general's judgement about the most suitable candidate for prime minister has to be brought into play. The governor-general must additionally appoint to Cabinet, at the direction of the prime minister, at least five other ministers of the Crown.[17] All ministers are accountable to the democratically elected House of Assembly and, through it, to the people. The Queen is informed by her viceroy of the acceptance of the resignation of a prime minister and the swearing-in of a new prime minister and other members of the ministry, she remains fully briefed through regular communications from her Barbadian ministers, and she holds audience with them where possible.[2] Members of various executive agencies and other officials are appointed by the Crown. The commissioning of privy councillors, senators, the Speaker of the Senate, and Supreme Court justices also falls under the Royal Prerogative. Public inquiries are also commissioned by the Crown through a Royal Warrant and are called Royal Commissions.

The Royal Prerogative further extends to foreign affairs: the governor-general ratifies treaties, alliances, and international agreements. As with other uses of the Royal Prerogative, no parliamentary approval is required. However, a treaty cannot alter the domestic laws of Barbados; an Act of Parliament is necessary in such cases. The governor-general, on behalf of the Queen, also accredits Barbadian High Commissioners and ambassadors and receives diplomats from foreign states. In addition, the issuance of passports falls under the Royal Prerogative and, as such, all Barbadian passports are issued in the monarch's name.

Parliament (Queen-in-Parliament)

The sovereign, along with the Senate and the House of Assembly, is one of the three components of parliament,[18] called the Queen-in-Parliament. The authority of the Crown therein is embodied in the mace, which bears a crown at its apex; unlike other realms, however, the Barbados parliament only has a mace for the lower house.[19] The monarch does not, however, participate in the legislative process; the viceroy does, though only in the granting of Royal Assent.[20] Further, the constitution outlines that the governor-general alone is responsible for appointing senators. As in some other countries, such as Canada, the viceroy must make some senatorial appointments on the advice of the prime minister. However, uniquely, the constitution stipulates that two senators are to be appointed in consultation with the leader of the opposition and seven appointed by the governor-general acting at his own discretion.[21] The viceroy additionally summons, prorogues, and dissolves parliament;[22] after the latter, the writs for a general election are usually dropped by the governor-general at Government House. The new parliamentary session is marked by the State Opening of Parliament, during which either the monarch or the governor-general reads the Speech from the Throne. As the monarch and viceroy cannot enter the House of Assembly, this, as well as the bestowing of Royal Assent, takes place in the Senate chamber; Members of Parliament are summoned to these ceremonies from the Commons by the Crown's messenger, the Usher of the Black Rod, after he knocks on the doors of the lower house that have been slammed closed on him, to symbolise the barring of the monarch from the assembly.

All laws in Barbados are enacted only with the viceroy's granting of Royal Assent in the monarch's name.[20] Thus, all bills begin with the phrase "Her Majesty, by virtue and in exercise of the powers vested in Her by section 5 of the Barbados Independence Act 1966 and of all other powers enabling Her in that behalf, is pleased, by and with the advice of Her Privy Council, to order, and it is hereby ordered, as follows..."[23]

Courts (Queen-on-the-Bench)

The sovereign is deemed the fount of justice, and is responsible for rendering justice for all subjects, known in this role as the Queen on the Bench. However, he or she does not personally rule in judicial cases; instead, judicial functions are performed in his or her name. Hence, the common law holds that the sovereign "can do no wrong"; the monarch cannot be prosecuted in his or her own courts for criminal offences. Civil lawsuits against the Crown in its public capacity (that is, lawsuits against the government) are permitted; however, lawsuits against the monarch personally are not cognizable. In international cases, as a sovereign and under established principles of international law, the Queen of Barbados is not subject to suit in foreign courts without her express consent. The sovereign, and by extension the governor-general, also exercises the prerogative of mercy,[24] and may pardon offences against the Crown, either before, during, or after a trial. In addition, the monarch also serves as a symbol of the legitimacy of courts of justice and of their judicial authority. An image of the Queen or the Arms of Her Majesty in Right of Barbados is always displayed in Barbadian courtrooms. Judges also have a pair of white gloves from the Queen on display on the edge of the bench, which marks the authority of the court, similar to the ceremonial mace of parliament.

Cultural role

From the beginning of Queen Elizabeth II's reign onwards, royal symbols in Barbados were altered to make them distinctly Barbadian or new ones created, such as the Royal Arms of Barbados (presented on 14 February 1966 by the Queen to then President of the Senate Sir Grey Massiah)[25][26] and the Queen's Royal Standard for Barbados, created in 1975.[27] Second in precedence is the personal flag of the governor-general.

The main symbol of the monarchy is the sovereign herself. Thus, portraits of her are displayed in public buildings and on stamps.[28][29] A crown is also used to illustrate the monarchy as the locus of authority, appearing on police force and Barbados Defence Force regimental and maritime badges and rank insignia, as well as Barbadian honours, the system of such created through Letters Patent issued by Queen Elizabeth II in July 1980.[26]

History

The current Barbadian monarchy can trace its ancestral lineage back to the Anglo-Saxon period and, ultimately, back to the kings of the Angles and the early Scottish kings. The Crown in Barbados has grown over the centuries since the Barbados was claimed under King James VI of Scotland and I of England in 1625, though not colonised until 1627, when, in the name of King Charles I, Governor Charles Wolferstone established the first settlement on the island.[30] By the 18th century, Barbados became one of the main seats of British authority in the British West Indies, though, due to the economic burden of duties and trade restrictions, some Barbadians, including the Clerk of the General Assembly, attempted to declare in 1727 that the Act of Settlement 1701 had expired in the colony, since the Governor, Henry Worsley, had not received a new commission from King George II upon his accession to the throne. Thus, they refused to pay their taxes to a governor they recognised as having no authority. The Attorney and Solicitor General of Great Britain confirmed that Worsley was entitled to collect the dues owed, but, Worsley resigned his post before the directive arrived in Barbados.[31]

After attempting in 1958 a federation with other West Indian colonies, similar to that of fellow Commonwealth realms Canada and Australia, continued as a self-governing colony under the Colonial Office, until independence came with the signing of the Barbados Independence Order by Queen Elizabeth II. In the same year, Elizabeth's cousin, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, opened the second session of the first parliament of the newly established country,[30] before the Queen herself, along with her husband, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, toured Barbados, opening Barclays Park,[32] in Saint Andrew, amongst other events. Elizabeth returned for her Silver Jubilee in 1977, after addressing the new session of parliament, she departed on the Concorde, which was the Queen's first supersonic flight.[30] She also was in Barbados in 1989, to mark the 350th anniversary of the establishment of the Barbados parliament, where she sat to receive addresses from both houses.[2][30] In 2016 the Queen shared person congratulations to the people and government of Barbados on reaching 50 years of political independence and touched on her family's fondness of Barbados and witnessing development of nation over that time.[33]

Republicanism

Former Prime Minister Owen Arthur called for a referendum on becoming a republic to be held in 2005.[34] It was announced on 26 November 2007 that the referendum would be held in 2008, together with the general election.[35] On 2 December 2007, reports emerged that this vote was put off due to concerns raised by the Electoral and Boundaries Commission.[36] Following the election, David Thompson replaced Arthur as prime minister.

On 22 March 2015, Prime Minister Freundel Stuart announced his intention to move the country towards a republican form of government "in the very near future".[37] The general secretary of the Democratic Labour Party, George Pilgrim, confirmed the move and said that it is expected to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Barbadian independence in 2016.[38] According to the country's constitution, a two-thirds majority in parliament is needed to authorize the change; The Democratic Labour Party has a two-thirds majority in the Senate, but not in the House of Assembly, where it would need the support of the opposition Barbados Labour Party to approve the transition. Opposition leader Mia Mottley has not commented on the Prime Minister's proposal.[39]

See also

- List of Commonwealth visits made by Queen Elizabeth II

- Monarchies in the Americas

- List of monarchies

Notes

- The English Court of Appeal ruled in 1982, while "there is only one person who is the Sovereign within the British Commonwealth... in matters of law and government the Queen of the United Kingdom, for example, is entirely independent and distinct from the Queen of Canada."[1]

- During the 1990 Jamaat al Muslimeen coup attempt in nearby Trinidad and Tobago, all branches of government were successfully captured on the island, leading to the president and cabinet having to sign an amnesty to return toward governance.

- Justice Rouleau in a 2003 Ontario court ruling wrote that "Union under the... Crown together with other Commonwealth countries [is a] constitutional principle".[8]

Citations

- R v Foreign Secretary, Ex parte Indian Association (as referenced in High Court of Australia: Sue v Hill [1999] HCA 30; 23 June 1999; S179/1998 and B49/1998), QB 892 at 928 (English Court of Appeal June 1999).

- Royal Household. "The Queen and Commonwealth > Other Caribbean Realms". Queen's Printer.

- Mallory, J.R. (August 1956). "Seals and Symbols: From Substance to Form in Commonwealth Equality". The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. Montreal: Blackwell Publishing. 22 (3): 281–291. ISSN 0008-4085. JSTOR 138434.

- Anglican Church Worldwide. "Barbados". Archived from the original on 15 May 2013.

- Elizabeth II (2002), Constitution of Barbados (PDF), Bridgetown: Government Printer, p. 37, IV.29(1a), (1b), (1c), retrieved 3 May 2015

- A, C (4 October 2006). "Tull: Tell us about coup rumours". Nation Newspaper. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- Mackinlay, Andrew (10 March 2005). "Early day motion 895: MORGANATIC MARRIAGE AND THE STATUTE OF WESTMINSTER 1931". London: British Parliament. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- O'Donohue v. Her Majesty The Queen in Right of Canada and Her Majesty The Queen in Right of Ontario, 2003 CanLII 41404, paragraphs 3 and 24 (Ontario Superior Court of Justice 26 June 2003).

- Elizabeth II (2013), An Act to provide for the Parliament of Barbados to acquiesce to alterations in the law relating to the succession to the Throne of the United Kingdom (PDF), Bridgetown: Government Information Service, retrieved 31 March 2015

- "The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II".

- Constitution of Barbados; First Schedule Archived 5 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Cox, Noel; Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law: Black v Chrétien: Suing a Minister of the Crown for Abuse of Power, Misfeasance in Public Office and Negligence; Volume 9, Number 3 (September 2002)

- Elizabeth II 2002, IV.28

- Elizabeth II 2002, IV.32(1)

- Elizabeth II 2002, IV.32(2)

- Elizabeth II 2002, VI.65(1)

- Elizabeth II 2002, VI.64(1)

- Elizabeth II 2002, V.35

- Parliament of Barbados. "The Mace of the House of Assembly". Government Printer. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008.

- Elizabeth II 2002, V.58(1)

- Elizabeth II 2002, 36(3)-(4)

- Elizabeth II 2002, 61(1)-(2)

- Elizabeth II (1966), Barbados Independence Order, archived from the original on 7 July 2006

- Elizabeth II 2002, VI.78(1)-(4)

- "National Symbols: Barbados". Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- Parliament of Barbados. "The Barbados Parliament: Independence". Government Printer. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008.

- "Flag of Queen Elizabeth II in Barbados". Flags of the World.

- Barbados Postal Service. "The Golden Jubilee". Government Printer. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- Barbados Postal Service. "The Golden Jubilee Souvenir Sheet". Government Printer. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- "Parliament's History". The Barbados Parliament. Archived from the original on 23 May 2007.

- Schomburgk, Robert Hermann (1848). The History of Barbados. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 318.

- Guide, Barbados.org Travel. "Barclays Park, Barbados".

- A message from Her Majesty The Queen to the people of Barbados on the 50th Anniversary of Independence, Published 30 November 2016, ELIZABETH R.

- Thomas, Norman "Gus" (7 February 2005). "Barbados to vote on move to republic". Caribbean Net News. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2006.

- Staff writer (26 November 2007). "Referendum on Republic to be bundled with election". Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- Gollop, Chris (2 December 2007). "Vote Off". The Nation. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- "PM says Barbados moving towards Republic". Jamaica Observer. 23 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- "Barbados plans to replace Queen with ceremonial president". The Guardian. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- "Barbados wants to ditch the Queen on the 50th anniversary of its independence". The Independent. Associated Press. 14 December 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

References

- Burleigh, Craig (2017). "Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee in Barbados ends with her first flight on Concorde on a record setting flight back to London Heathrow". Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- Elizabeth II (January 2010). "Queen and Barbados: Royal visits". Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

External links

- Queen's Official website on Barbados

- Diamond Jubilee Celebration for Queen Elizabeth II on YouTube, Visits to Barbados by the Royal Family over the decades