Felidae

Felidae is a family of mammals in the order Carnivora, colloquially referred to as cats, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a felid.[3][4][5][6] The term "cat" refers both to felids in general and specifically to the domestic cat (Felis catus).[7]

| Felidae[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae Fischer von Waldheim, 1817 |

| Type genus | |

| Felis | |

| Subfamilies | |

| |

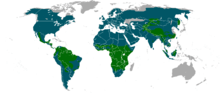

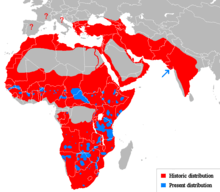

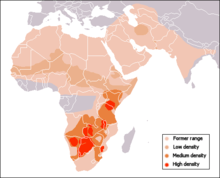

| Felidae ranges | |

Felidae species exhibit the most diverse fur pattern of all terrestrial carnivores.[8] Cats have retractile claws, slender muscular bodies and strong flexible forelimbs. Their teeth and facial muscles allow for a powerful bite. They are all obligate carnivores, and most are solitary predators ambushing or stalking their prey. Wild cats occur in Africa, Europe, Asia and the Americas. Some wild cat species are adapted to forest habitats, some to arid environments, and a few also to wetlands and mountainous terrain. Their activity patterns range from nocturnal and crepuscular to diurnal, depending on their preferred prey species.[9]

Reginald Innes Pocock divided the extant Felidae into three subfamilies: the Pantherinae, the Felinae and the Acinonychinae, differing from each other by the ossification of the hyoid apparatus and by the cutaneous sheaths which protect their claws.[10] This concept has been revised following developments in molecular biology and techniques for analysis of morphological data. Today, the living Felidae are divided in two subfamilies: the Pantherinae and Felinae, with the Acinonychinae subsumed into the latter. Pantherinae includes five Panthera and two Neofelis species, while Felinae includes the other 34 species in ten genera.[11]

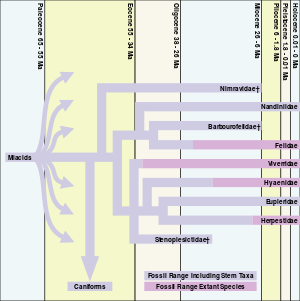

The first cats emerged during the Oligocene about 25 million years ago, with the appearance of Proailurus and Pseudaelurus. The latter species complex was ancestral to two main lines of felids: the cats in the extant subfamilies and a group of extinct cats of the subfamily Machairodontinae, which include the saber-toothed cats such as the Smilodon. The "false sabre-toothed cats", the Barbourofelidae and Nimravidae, are not true cats, but are closely related. Together with the Felidae, Viverridae, hyaenas and mongooses, they constitute the Feliformia.[7]

Characteristics

All members of the cat family have the following characteristics in common:

- They are digitigrade, have five toes on their forefeet and four on their hind feet. Their curved claws are protractile and attached to the terminal bones of the toe with ligaments and tendons. The claws are guarded by cutaneous sheaths, except in the Acinonyx.[12]

- They actively protract the claws by contracting muscles in the toe,[9] and they passively retract them. The dewclaws are expanded but do not protract.[13]

- They have 30 teeth with a dental formula of 3.1.3.13.1.2.1. The upper third premolar and lower molar are adapted as carnassial teeth, suited to tearing and cutting flesh.[14] The canine teeth are large, reaching exceptional size in the extinct saber-toothed species. The lower carnassial is smaller than the upper carnassial and has a crown with two compressed blade-like pointed cusps.[9]

- Their nose projects slightly beyond the lower jaw.[12]

- They have well developed and highly sensitive whiskers above the eyes, on the cheeks, on the muzzle, but not below the chin.[12] Whiskers help to navigate in the dark and to capture and hold prey.[13]

- Their skull is foreshortened with a rounded profile and large orbits.[13]

- Their tongue is covered with horny papillae, which rasp meat from prey and aid in grooming.[13]

- Their eyes are relatively large, situated to provide binocular vision. Their night vision is especially good due to the presence of a tapetum lucidum, which reflects light back inside the eyeball, and gives felid eyes their distinctive shine. As a result, the eyes of felids are about six times more light sensitive than those of humans, and many species are at least partially nocturnal. The retina of felids also contains a relatively high proportion of rod cells, adapted for distinguishing moving objects in conditions of dim light, which are complemented by the presence of cone cells for sensing colour during the day.[9]

- Their external ears are large, and especially sensitive to high-frequency sounds in the smaller cat species. This sensitivity allows them to locate small rodent prey.[9]

- They have lithe and flexible bodies with muscular limbs.[9]

- The plantar pads of both fore and hind feet form compact three-lobed cushions.[14]

- The penis is subconical and boneless,[12] facing backward when not erect.[15] Relative to body size, they have shorter bacula than canids.[16]

- They cannot detect the sweetness of sugar, as they lack the sweet-taste receptor.[17]

- Felids have a vomeronasal organ in the roof of the mouth, allowing them to "taste" the air.[18] The use of this organ is associated with the Flehmen response.[19]

- The standard sounds made by all felids include meowing, spitting, hissing, snarling and growling. Meowing is the main contact sound, whereas the others signify an aggressive motivation.[9]

- They can purr during both phases of respiration, though pantherine cats seem to purr only during oestrus and copulation, and as cubs when suckling. Purring is generally a low pitch sound of less than 2 kHz and mixed with other vocalization types during the expiratory phase.[20]

The colour, length and density of their fur is very diverse. Fur colour covers the gamut from white to black, and fur pattern from distinctive small spots, stripes to small blotches and rosettes. Most cat species are born with a spotted fur, except the jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi), Asian golden cat (Catopuma temminckii) and caracal (Caracal caracal). The spotted fur of lion (Panthera leo) and cougar (Puma concolor) cubs change to a uniform fur during their ontogeny.[8] Those living in cold environments have thick fur with long hair, like the snow leopard (Panthera uncia) and the Pallas's cat (Otocolobus manul).[13] Those living in tropical and hot climate zones have short fur. Several species exhibit melanism with all-black individuals.[9]

In the great majority of cat species, the tail is between a third and a half of the body length, although with some exceptions, like the Lynx species and margay.[9] Cat species vary greatly in body and skull sizes, and weights:

- The largest cat species is the tiger (Panthera tigris), with a head-to-body length of up to 390 cm (150 in), a weight range of at least 65 to 325 kg (143 to 717 lb), and a skull length ranging from 316 to 413 mm (12.4 to 16.3 in).[9][21] Although the maximum skull length of a lion is slightly greater at 419 mm (16.5 in), it is generally smaller in head-to-body length than the former.[22]

- The smallest cat species are the rusty-spotted cat (Prionailurus rubiginosus) and the black-footed cat (Felis nigripes). The former is 35–48 cm (14–19 in) in length and weighs 0.9–1.6 kg (2.0–3.5 lb).[9] The latter has a head-to-body length of 36.7–43.3 cm (14.4–17.0 in) and a maximum recorded weight of 2.45 kg (5.4 lb).[23][24]

Most cat species have a haploid number of 18 or 19. Central and South American cats have a haploid number of 18, possibly due to the combination of two smaller chromosomes into a larger one.[25]

Evolution

The family Felidae is part of the Feliformia, a suborder that diverged probably about 50.6 to 35 million years ago into several families.[26] The Felidae and the Asiatic linsangs are considered a sister group, which split about 35.2 to 31.9 million years ago.[27]

The earliest cats probably appeared about 35 to 28.5 million years ago. Proailurus is the oldest known cat that occurred after the Eocene–Oligocene extinction event about 33.9 million years ago; fossil remains were excavated in France and Mongolia's Hsanda Gol Formation.[7] Fossil occurrences indicate that the Felidae arrived in North America earliest 25 million years ago. This is about 20 million years ago later than the Ursidae and the Nimravidae, and about 10 million years later than the Canidae.[28]

In the Early Miocene about 20 to 16.6 million years ago, Pseudaelurus lived in Africa. Its fossil jaws were also excavated in geological formations of Europe's Vallesian, Asia's Middle Miocene and North America's late Hemingfordian to late Barstovian epochs.[29]

In the Early or Middle Miocene, the sabre-toothed Machairodontinae evolved in Africa and migrated northwards in the Late Miocene.[30] With their large upper canines, they were adapted to prey on large-bodied megaherbivores.[31][32] Miomachairodus is the oldest known member of this subfamily. Metailurus lived in Africa and Eurasia about 8 to 6 million years ago. Several Paramachaerodus skeletons were found in Spain. Homotherium appeared in Africa, Eurasia and North America around 3.5 million years ago, and Megantereon about 3 million years ago. Smilodon lived in North and South America from about 2.5 million years ago. This subfamily became extinct in the Late Pleistocene.[30]

Results of mitochondrial analysis indicate that the living Felidae species descended from a common ancestor, which originated in Asia in the Late Miocene epoch. They migrated to Africa, Europe and the Americas in the course of at least 10 migration waves during the past ~11 million years. Low sea levels, interglacial and glacial periods facilitated these migrations.[33] Panthera blytheae is the oldest known pantherine cat dated to the late Messinian to early Zanclean ages about 5.95 to 4.1 million years ago. A fossil skull was excavated in 2010 in Zanda County on the Tibetan Plateau.[34] Panthera palaeosinensis from North China probably dates to the Late Miocene or Early Pliocene. The skull of the holotype is similar to that of a lion or leopard.[35] Panthera zdanskyi dates to the Gelasian about 2.55 to 2.16 million years ago. Several fossil skulls and jawbones were excavated in northwestern China.[36] Panthera gombaszoegensis is the earliest known pantherine cat that lived in Europe about 1.95 to 1.77 million years ago.[37]

Living felids fall into eight evolutionary lineages or species clades.[38][39] Genotyping of nuclear DNA of all 41 felid species revealed that hybridization between species occurred in the course of evolution within the majority of the eight lineages.[40]

Modelling of felid coat pattern transformations revealed that nearly all patterns evolved from small spots.[41]

Classification

Traditionally, five subfamilies have been distinguished within the Felidae based on phenotypical features: the Pantherinae, the Felinae, the Acinonychinae,[10] and the extinct Machairodontinae and Proailurinae.[2]

Living species

The following table shows the living genera within the Felidae, grouped according to the traditional phenotypical classification.[11] Estimated genetic divergence times of the corresponding eight genotypical evolutionary lineages are indicated in million years ago (Mya), based on analysis of autosomal, xDNA, yDNA and mtDNA gene segments;[33] and estimates based on analysis of biparental nuclear genomes.[40]

| Genus | Species | IUCN Red List status and distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Neofelis Gray, 1867[42] [Lineage 1: 14.45 to 8.38 Mya] |

Clouded leopard (N. nebulosa) (Griffith, 1821)[43]

diverged 9.32 to 4.47 Mya |

VU[44]

|

| Sunda clouded leopard (N. diardi) (Cuvier, 1823)[45]

diverged 2 to 0.9 Mya[46] |

VU[47]

| |

| Panthera Oken, 1816[48] [Lineage 1]; 11.75 to 0.97 Mya[40] |

Leopard (P. pardus) (Linnaeus, 1758)[49]

diverged 4.63 to 1.81 Mya |

VU[50]

|

| Tiger (P. tigris) (Linnaeus, 1758)[51]

diverged 4.62 to 1.82 Mya |

EN[52]

| |

| Snow leopard (P. uncia) (Schreber, 1775)[53]

diverged 4.62 to 1.82 Mya |

VU[54]

| |

| Lion (P. leo) (Linnaeus, 1758)[55]

diverged 3.46 to 1.22 Mya |

VU[56]

| |

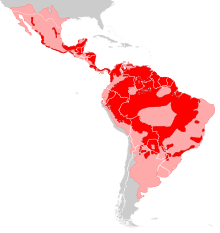

| Jaguar (P. onca) (Linnaeus, 1758)[57]

diverged 3.46 to 1.22 Mya |

NT[58]

|

| Genus | Species | IUCN Red List status and distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Pardofelis Severtzov, 1858[59] [Lineage 2: 12.77 to 7.36 Mya] |

Marbled cat (P. marmorata) (Martin, 1836)[60]

diverged 8.42 to 4.27 Mya |

NT[61]

|

| Catopuma Severtzov, 1858[59] [Lineage 2]; 8.47 to 0.41 Mya[40] |

Asian golden cat (C. temminckii) (Vigors & Horsfield, 1827)[62]

diverged 6.42 to 2.96 Mya; 4.58 to 0.03 Mya[40] |

NT[63]

|

| Bay cat (C. badia) (Gray, 1874)[64]

diverged 6.42 to 2.96 Mya; 4.58 to 0.03 Mya[40] |

EN[65]

| |

| Leptailurus Severtzov, 1858[59] [Lineage 3: 11.56 to 6.66 Mya] |

Serval (L. serval) (Schreber, 1775)[66]

diverged 7.91 to 4.14 Mya |

LC[67]

|

| Caracal Gray, 1843[68] [Lineage 3]; 11.99 to 3.64 Mya[40] |

Caracal (C. caracal) (Schreber, 1776)[69]

diverged 2.93 to 1.19 Mya; 6.25 to 0.07 Mya[40] |

LC[70]

|

| African golden cat (C. aurata) (Temminck, 1827)[71]

diverged 2.93 to 1.19 Mya; 6.25 to 0.07 Mya[40] |

VU[72]

| |

| Leopardus Gray, 1842[73] [Lineage 4: 10.95 to 6.3 Mya]; 5.19 to 0.93 Mya[40] |

Pampas cat (L. colocola) (Molina, 1782)[74]

diverged 2.70 to 1.18 Mya |

NT[75]

|

| Andean mountain cat (L. jacobitus) (Cornalia, 1865)[76]

diverged 2.70 to 1.18 Mya |

EN[77]

| |

| Ocelot (L. pardalis) (Linnaeus, 1758)[78]

diverged 2.41 to 1.01 Mya; 4.76 to 0.05 Mya[40] |

LC[79]

| |

| Margay (L. wiedii) (Schinz, 1821)[80]

diverged 2.41 to 1.01 Mya; 4.76 to 0.05 Mya[40] |

NT[81]

| |

| Kodkod (L. guigna) (Molina, 1782)[74]

diverged 1.48 to 0.56 Mya; 4.64 to 0.04 Mya[40] |

VU[82]

| |

| Geoffroy's cat (L. geoffroyi) (d'Orbigny & Gervais, 1844)[83]

diverged 1.48 to 0.56 Mya; 4.64 to 0.04 Mya[40] |

LC[84]

| |

| Oncilla (L. tigrinus) (Schreber, 1775)[85]

diverged 1.48 to 0.56 Mya |

VU[86]

| |

| Southern tigrina (L. guttulus) (Hensel, 1872)[87]

diverged 0.8 to 0.5 Mya[88] |

VU[89]

| |

| Lynx Kerr, 1792[90] [Lineage 5: 9.81 to 5.62 Mya]; 8.67 to 2.39 Mya[40] |

Bobcat (L. rufus) (Schreber, 1777)[91]

diverged 4.74 to 2.53 Mya |

LC[92]

|

| Canada lynx (L. canadensis) Kerr, 1792[90]

diverged 2.6 to 1.06 Mya |

LC[93]

| |

| Eurasian lynx (L. lynx) (Linnaeus, 1758)[94]

diverged 1.98 to 0.7 Mya |

LC[95]

| |

| Iberian lynx (L. pardinus) (Temminck, 1827)[96]

diverged 1.98 to 0.7 Mya |

EN[97]

| |

| Acinonyx Brookes, 1828[98] [Lineage 6: 9.20 to 5.27 Mya] |

Cheetah (A. jubatus) Schreber, 1775)[99]

diverged 6.92 to 3.86 Mya |

VU[100]

|

| Puma Jardine 1834[101] [Lineage 6] |

Cougar (P. concolor) Linnaeus, 1771[102]

diverged 6.01 to 3.16 Mya |

LC[103]

|

| Herpailurus Severtzov, 1858[59] [Lineage 6] |

Jaguarundi (H. yagouaroundi) (Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1803)[104]

diverged 6.01 to 3.16 Mya |

LC[105]

|

| Otocolobus Brandt, 1842[106] [Lineage 7: 8.55 to 4.8 Mya]; 9.4 to 1.46 Mya[40] |

Pallas's cat (O. manul) (Pallas, 1776)[107]

diverged 8.16 to 4.53 Mya |

NT[108]

|

| Prionailurus Severtzov, 1858[59] [Lineage 7]; 8.76 to 0.73 Mya[40] |

Rusty-spotted cat (P. rubiginosus) (Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1834)[109]

diverged 6.54 to 3.42 Mya |

NT[110]

|

| Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) (Kerr, 1792)[111]

diverged 4.31 to 2.04 Mya |

LC[112]

| |

| Fishing cat (P. viverrinus) (Bennett, 1833)[113]

diverged 3.82 to 1.74 Mya |

VU[114]

| |

| Flat-headed cat (P. planiceps) (Vigors & Horsfield, 1827)[62]

diverged 3.82 to 1.74 Mya |

VU[115]

| |

| Sunda leopard cat (P. javanensis) (Desmarest, 1816)[116]

diverged 1.3 to 0.56 Mya[117] |

| |

| Felis Linnaeus, 1758[118] [Lineage 8: 4.88 to 2.41 Mya]; 6.52 to 1.03 Mya[40] |

Jungle cat (F. chaus) Schreber, 1777[119]

diverged 4.88 to 2.41 Mya |

LC[120]

|

| Black-footed cat (F. nigripes) Burchell, 1824[121]

diverged 4.44 to 2.16 Mya |

VU[122]

| |

| Sand cat (F. margarita) Loche, 1858[123]

diverged 3.67 to 1.72 Mya |

LC[124]

| |

| Chinese mountain cat (F. bieti) Milne-Edwards, 1892[125]

diverged 1.86 to 0.72 Mya |

VU[126]

| |

| African wildcat (F. lybica) Forster, 1780[127]

diverged 1.86 to 0.72 Mya |

| |

| European wildcat (F. silvestris) Schreber, 1777[128]

diverged 1.62 to 0.59 Mya |

LC[129]

| |

| Domestic cat (F. catus) Linnaeus, 1758[118]

|

Phylogeny

The phylogenetic relationships of living felids are shown in the following cladogram:[33][40]

| Felidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prehistoric taxa

- Proailurinae

- Proailurus (Filhol, 1879)[130]

- Pseudailurus grade

- Pseudaelurus (Gervais, 1850)[132][7]

- P. quadridentatus (Blainville, 1882)

- P. guangheesis (Cao et al, 1990)

- P. cuspidatus (Wang et al, 1998)

- Sivaelurus (Pilgrim, 1910)

- S. chinjiensis (Pilgrim, 1910)

- Hyperailurictis (Kretzoi, 1929)

- H. intrepidus (Leidy, 1858)

- H. marshi (Thorpe, 1922)

- H. stouti (Schultz & Martin, 1972)

- H. validus (Rothwell, 2001)

- H. skinneri (Rothwell, 2003)

- Styriofelis (Kretzoi, 1929)

- S. turnauensis (Deperet, 1892)

- S. romieviensis (Roman & Viret, 1934)

- Miopanthera (Kretzoi, 1938)

- M. lorteti (Gaillard, 1899)

- M. pamiri (Ozansoy, 1965)

- Pseudaelurus (Gervais, 1850)[132][7]

- Pantherinae

- Panthera

- P. spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810)[133]

- P. atrox (Leidy, 1853)[134]

- P. fossilis (Reichenau, 1906)

- P. palaeosinensis (Zdansky, 1924)

- P. youngi (Pei, 1934)

- P. gombaszoegensis (Kretzoi, 1938)[135]

- P. shawi (Broom, 1948)

- P. zdanskyi (Mazák, Christiansen & Kitchener, 2011)[36]

- P. blytheae (Tseng et al., 2013)[34]

- P. balamoides (Stinnesbeck et al., 2019)

- P. leo

- P. onca

- P. onca augusta (Leidy, 1872)

- P. onca mesembrina (Cabrera 1934)

- P. pardus

- P. pardus spelaea (Bächler, 1936)

- P. tigris

- P. tigris trinilensis (Dubois, 1908)

- P. tigris soloensis (Koenigswald, 1933)

- Panthera

- Felinae

- Felis

- F. lunensis (Martelli, 1906)

- Lynx

- L. issiodorensis (Croizet & Jobert, 1828)

- L. rexroadensis (Stephens, 1959)[136][137]

- L. thomasi

- Puma

- P. pardoides (Owen, 1846)

- P. pumoides (Castellanos, 1956)

- Acinonyx

- A. pardinensis (Croizet & Jobert, 1828)

- A. intermedius (Thenius, 1954)[7]

- A. aicha (Geraads, 1997)

- Sivapanthera (Kretzoi, 1929)

- S. arvernensis (Croizet & Jobert, 1828)

- S. brachygnathus (Lydekker, 1884)

- S. pleistocaenicus (Zdansky, 1925)

- S. potens (Pilgrim, 1932)

- S. linxiaensis (Qiu et al., 2004)

- S. padhriensis (Ghaffar & Akhtar, 2004)

- Pratifelis (Hibbard, 1934)

- P. martini (Hibbard, 1934)

- Miracinonyx (Adams, 1979)[138]

- M. inexpectatus (Cope, 1895)

- M. trumani (Orr, 1969)

- Diamantofelis (Morales, Pickford, Soria & Fraile, 1998)[139]

- D. ferox (Morales, Pickford, Soria & Fraile, 1998)

- Namafelis (Morales, Pickford, Fraile, Salesa & Soria, 2003)[140]

- N. minor (Morales, Pickford, Fraile, Salesa & Soria, 2003)

- Asilifelis (Werdelin, 2011)[141]

- A. coteae Werdelin, 2011

- Leptofelis (Salesa et al., 2012)

- L. vallesiensis (Salesa et al., 2012)

- Pristifelis (Salesa et al., 2012)

- Katifelis (Adrian, Werdelin & Grossman, 2018)[142]

- K. nightingalei (Adrian, Werdelin & Grossman, 2018)

- Felis

- Machairodontinae

- Tchadailurus (Salesa et al., 2012)

- T. adei (Bonis et al., 2018)

- Tribe Metailurini:

- Metailurus (Zdansky, 1924)[143]

- M. major (Zdansky, 1924)

- M. mongoliensis (Colbert, 1939)

- M. ultimus (Li, 2014)

- M. boodon

- Adelphailurus (Hibbard, 1934)

- A. kansensis (Hibbard, 1934)

- Stenailurus

- S. teilhardi

- Dinofelis (Zdansky, 1924)[30][144]

- D. aronoki

- D. barlowi

- D. cristata

- D. darti

- D. diastemata

- D. paleoonca

- D. petteri

- D. piveteaui

- Yoshi (Spassov and Geraads, 2014)[145]

- Y. minor (Zdansky, 1924)

- Y. garevskii (Spassov and Geraads, 2014)

- Metailurus (Zdansky, 1924)[143]

- Tribe Smilodontini:

- Megantereon (Croizet & Jobert, 1828)

- M. cultridens (Cuvier, 1824)

- M. nihowanensis (Teilhard de Chardin & Piveteau, 1930)

- M. hesperus (Gazin, 1933)

- M. whitei (Broom, 1937)

- M. inexpectatus (Tielhard de Chardin, 1939)

- M. vakshensis (Sarapov, 1986)

- M. ekidoit (Werdelin & Lewis, 2000)

- M. microta (Zhu et al., 2015)

- Smilodon (Lund, 1842)

- S. populator (Lund, 1842)

- S. fatalis (Leidy, 1869)

- S. gracilis (Cope, 1880)

- Paramachairodus (Pilgrim, 1913)

- P. maximiliani

- P. orientalis

- P. transasiaticus

- Promegantereon (Kretzoi, 1938)[143]

- P. ogygia (Kretzoi, 1938)

- Rhizosmilodon (Wallace & Hulbert, 2013)

- R. fiteae (Wallace & Hulbert, 2013)

- Megantereon (Croizet & Jobert, 1828)

- Tribe Homotherini:

- Homotherium (Fabrini, 1890)

- H. latidens (Owen, 1846)

- H. serum (Cope, 1893)

- H. ischyrus (Merriam, 1905)

- H. venezuelensis (Rincón et al., 2011)

- Amphimachairodus (Kretzoi, 1929)[143]

- A. giganteus (Kretzoi, 1929)

- A. kurteni (Sotnikova, 1992)

- A. coloradensis (Anton et al., 2013)

- A. alvarezi (Ruiz-Ramoni et al., 2019)

- Nimravides (Kitts, 1958)[143]

- N. catacopsis (Cope, 1887)

- N. pedionomus (MacDonald, 1948)

- N. thinobates (MacDonald, 1948)

- N. hibbardi (Dalquest, 1969)

- N. galiani (Baskin, 1981)

- Xenosmilus (Martin et al., 2000)

- X. hodsonae (Martin et al., 2000)

- Lokotunjailurus (Werdelin, 2003)

- L. emageritus (Werdelin, 2003)

- L. fanonei (Bonis, Peigné, Mackaye, Likius, Vignaud & Brunet, 2010)

- Homotherium (Fabrini, 1890)

- Tribe Machairodontini:

- Machairodus (Kaup, 1833)[143]

- M. aphanistus (Kaup, 1832)

- M. horribilis (Schlosser, 1903)

- M. robinsoni (Kurtén, 1975)

- M. pseudaeluroides (Schmidt-Kittler 1976)

- M. alberdiae (Ginsburg et al., 1981)

- M. laskerevi (Sotnikova, 1992)

- M. kabir (Peigné et al., 2005)

- Hemimachairodus (Koenigswald, 1974)

- H. zwierzyckii (Koenigswald, 1974)

- Miomachairodus (Schmidt-Kittler 1976)

- M. pseudaeluroides (Schmidt-Kittler 1976)

- Machairodus (Kaup, 1833)[143]

- Tchadailurus (Salesa et al., 2012)

See also

- Cat gap

- Exotic felines as pets

- Felid hybrid

- List of felids

- List of largest cats

- Panthera hybrid

- Pinch-induced behavioral inhibition

References

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Felidae". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–548. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- McKenna, M. C.; Bell, S. K. (2000). "Family Felidae Fischer de Waldheim, 1817:372. Cats". Classification of Mammals. Columbia University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-231-11013-6.

- Salles, L. O. (1992). "Felid phylogenetics: extant taxa and skull morphology (Felidae, Aeluroidea)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3047).

- Hemmer, H. (1978). "Evolutionary systematics of living Felidae – present status and current problems". Carnivore. 1: 71–79.

- Johnson, W. E.; Dratch, P. A.; Martenson, J. S.; O'Brien, S. J. (1996). "Resolution of recent radiations within three evolutionary lineages of Felidae using mitochondrial restriction fragment length polymorphism variation". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 3 (2): 97–120. doi:10.1007/bf01454358.

- Christiansen, P. (2008). "Evolution of skull and mandible shape in cats (Carnivora: Felidae)". PLOS ONE. 3 (7): e2807. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2807C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002807. PMC 2475670. PMID 18665225.

- Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)". In Macdonald, D. W.; Loveridge, A. J. (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5.

- Peters, G. (1982). "Zur Fellfarbe und zeichnung einiger Feliden". Bonner Zoologische Beiträge. 33 (1): 19−31.

- Sunquist, M.; Sunquist, F. (2002). "What is a Cat?". Wild Cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 5–18. ISBN 978-0-226-77999-7.

- Pocock, R. I. (1917). "The classification of the existing Felidae". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Series 8. XX (119): 329–350. doi:10.1080/00222931709487018.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11.

- Pocock, R. I. (1917). "VII.—On the external characters of the Felidæ". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 8. 19 (109): 113−136. doi:10.1080/00222931709486916.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Van Valkenburgh, B.; Yamaguchi, N. (2010). "Felid form and function". In Macdonald, D.; Loveridge, A. (eds.). Biology and Conservation of wild felids. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 83−106.

- Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Felidae". The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 191–330.

- de Morais, Rosana Nogueira. "Reproduction in small felid males." Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of South American Wild Animals (2008): 312.

- Ewer, R. F. (1973). The Carnivores. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8493-3. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- Li, X.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Cao, J.; Maehashi, K.; Huang, L.; Bachmanov, A. A.; Reed, D. R.; Legrand-Defretin, V.; Beauchamp, G. K. & Brand, J. G. (2005). "Pseudogenization of a Sweet-Receptor Gene Accounts for Cats' Indifference toward Sugar". PLOS Genetics. 1 (1): 27–35. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010003. PMC 1183522. PMID 16103917.

- Salazar, I.; Quinteiro, P.; Cifuentes, J. M.; Caballero, T. G. (1996). "The vomeronasal organ of the cat". Journal of Anatomy. 188 (2): 445–454. PMC 1167581. PMID 8621344.

- Hart, B. L.; Leedy, M. G. (1987). "Stimulus and hormonal determinants of flehmen behavior in cats" (PDF). Hormones and Behavior. 21 (1): 44−52. doi:10.1016/0018-506X(87)90029-8. PMID 3557332.

- Peters, G. (2002). "Purring and similar vocalizations in mammals". Mammal Review. 32 (4): 245−271. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.2002.00113.x.

- Hewett, J. P.; Hewett Atkinson, L. (1938). Jungle trails in northern India: reminiscences of hunting in India. London: Metheun and Company Limited. Alt URL

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Tiger". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 95–202.

- Mills, M. G. L. (2005). "Felis nigripes Burchell, 1824 Black-footed cat". In Skinner, J. D.; Chimimba, C. T. (eds.). The mammals of the southern African subregion (Third ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 405−408. ISBN 9780521844185.

- Sliwa, A. (2004). "Home range size and social organization of black-footed cats (Felis nigripes)". Mammalian Biology. 69 (2): 96–107. doi:10.1078/1616-5047-00124.

- Vella, C.; Shelton, L. M.; McGonagle, J. J. & Stanglein, T. W. (2002). Robinson's Genetics for Cat Breeders and Veterinarians (Forth ed.). Oxford: Butterworh-Heinemann Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7506-4069-5.

- Eizirik, E.; Murphy, W. J.; Köpfli, K. P.; Johnson, W. E.; Dragoo, J. W. & O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Pattern and timing of the diversification of the mammalian order Carnivora inferred from multiple nuclear gene sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (1): 49–63. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.033. PMC 7034395. PMID 20138220.

- Gaubert, P. & Veron, G. (2003). "Exhaustive sample set among Viverridae reveals the sister-group of felids: the linsangs as a case of extreme morphological convergence within Feliformia". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 270 (1532): 2523–2530. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2521. PMC 1691530. PMID 14667345.

- Silvestro, D.; Antonelli, A.; Salamin, N. & Quental, T. B. (2015). "The role of clade competition in the diversification of North American canids". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (28): 8684−8689. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.8684S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1502803112. PMC 4507235. PMID 26124128.

- Rothwell, T. (2003). "Phylogenetic systematics of North American Pseudaelurus (Carnivora: Felidae)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 3403 (3403): 1−64. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2003)403<0001:PSONAP>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/2829.

- van den Hoek Ostende, L. W.; Morlo, M. & Nagel, D. (2006). "Majestic killers: the sabre-toothed cats" (PDF). Geology Today. Fossils explained 52. 22 (4): 150–157. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2451.2006.00572.x. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- Randau, M.; Carbone, Turvey; C., S. T. (2013). "Canine evolution in sabretoothed carnivores: natural selection or sexual selection?". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e72868. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...872868R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072868. PMC 3738559. PMID 23951334.

- Piras, P.; Silvestro, D.; Carotenuto, F.; Castiglione, S.; Kotsakis, A.; Maiorino, L.; Melchionna, M.; Mondanaro, A.; Sansalone, G.; Serio, C. & Vero, V. A. (2018). "Evolution of the sabertooth mandible: A deadly ecomorphological specialization". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 496: 166−174. Bibcode:2018PPP...496..166P. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.01.034.

- Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W. J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2006). "The Late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: a genetic assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146.

- Tseng, Z. J.; Wang, X.; Slater, G. J.; Takeuchi, G. T.; Li, Q.; Liu, J. & Xie, G. (2014). "Himalayan fossils of the oldest known pantherine establish ancient origin of big cats". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 281 (1774): 20132686. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2686. PMC 3843846. PMID 24225466.

- Mazak, J. H. (2010). "What is Panthera palaeosinensis?". Mammal Review. 40 (1): 90−102. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2009.00151.x.

- Mazák, J. H.; Christiansen, P. & Kitchener, A. C. (2011). "Oldest Known Pantherine Skull and Evolution of the Tiger". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25483. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625483M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025483. PMC 3189913. PMID 22016768.

- Argant, A. & Argant, J. (2011). "The Panthera gombaszogensis story: The contribution of the Château Breccia (Saône-Et-Loire, Burgundy, France)". Quaternaire. Hors-série (4): 247–269.

- Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (1997). "Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Felidae using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 mitochondrial genes". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 44 (Supplement 1): S98–S116. Bibcode:1997JMolE..44S..98J. doi:10.1007/PL00000060. PMID 9071018.

- O'Brien, S. J. & Johnson, W. E. (2005). "Big cat genomics". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 6: 407–429. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162151. PMID 16124868.

- Li, G.; Davis, B. W.; Eizirik, E. & Murphy, W. J. (2016). "Phylogenomic evidence for ancient hybridization in the genomes of living cats (Felidae)". Genome Research. 26 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1101/gr.186668.114. PMC 4691742. PMID 26518481.

- Werdelin, L. & Olsson, L. (2008). "How the leopard got its spots: a phylogenetic view of the evolution of felid coat patterns". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 62 (3): 383–400. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1997.tb01632.x.

- Gray, J. E. (1867). "Notes on the skulls of the Cats. 5. Neofelis". Proceedings of the Scientific Meetings of the Zoological Society of London. 1867: 265–266.

- Griffith, E. (1821). "Felis nebulosa". General and particular descriptions of the vertebrated animals arranged comfortably to the modern discoveries and improvements in zoology. London: Baldwin, Cradock & Joy. p. 37.

- Grassman, L.; Lynam, A.; Mohamad, S.; Duckworth, J. W.; Borah, J.; Willcox, D.; Ghimirey, Y.; Reza, A. & Rahman, H. (2016). "Neofelis nebulosa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T14519A97215090.

- Cuvier, G. (1823). "Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles; ou, l'on retablit les caracteres de plusiers animaux dont les revolutions du globe ont detruit les especes". Les Ruminans et les Carnassiers Fossiles, Volume IV. Paris: G. Dufour & E. d'Ocagne.

- Buckley-Beason, V. A.; Johnson, W. E.; Nash, W. G.; Stanyon, R.; Menninger, J. C.; Driscoll, C. A.; Howard, J.; Bush, M.; Page, J. E.; Roelke, M. E.; Stone, G.; Martelli, P.; Wen, C.; Ling, L.; Duraisingam, R. K.; Lam, V. P. & O'Brien, S. J. (2006). "Molecular Evidence for Species-Level Distinctions in Clouded Leopards". Current Biology. 16 (23): 2371–2376. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.066. PMC 5618441. PMID 17141620.

- Hearn, A.; Ross, J.; Brodie, J.; Cheyne, S.; Haidir, I. A.; Loken, B.; Mathai, J.; Wilting, A. & McCarthy, J. (2016). "Neofelis diardi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T136603A97212874.

- Oken, L. (1816). "1. Art, Panthera". Lehrbuch der Zoologie. 2. Abtheilung. Jena: August Schmid & Comp. p. 1052.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis pardus". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 41−42.

- Stein, A. B.; Athreya, V.; Gerngross, P.; Balme, G.; Henschel, P.; Karanth, U.; Miquelle, D.; Rostro, S.; Kamler, J. F. & Laguardia, A. (2016). "Panthera pardus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15954A102421779.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis tigris". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 41.

- Goodrich, J.; Lynam, A.; Miquelle, D.; Wibisono, H.; Kawanishi, K.; Pattanavibool, A.; Htun, S.; Tempa, T.; Karki, J.; Jhala, Y. & Karanth, U. (2015). "Panthera tigris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T15955A50659951.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1777). "Die Unze". Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther. pp. 386–387.

- McCarthy, T.; Mallon, D.; Jackson, R.; Zahler, P. & McCarthy, K. (2017). "Panthera uncia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22732A50664030.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis leo". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 41.

- Bauer, H.; Packer, C.; Funston, P. F.; Henschel, P. & Nowell, K. (2016). "Panthera leo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T15951A107265605.en.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis onca". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 42. (in Latin)

- Quigley, H.; Foster, R.; Petracca, L.; Payan, E.; Salom, R. & Harmsen, B. (2017). "Panthera onca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T15953A123791436.

- Severtzow, M. N. (1858). "Notice sur la classification multisériale des Carnivores, spécialement des Félidés, et les études de zoologie générale qui s'y rattachent". Revue et Magasin de Zoologie Pure et Appliquée. X: 385–396.

- Martin, W. C. (1836). "Description of a new species of Felis". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. IV (XLVII): 107–108.

- Ross, J.; Brodie, J.; Cheyne, S.; Datta, A.; Hearn, A.; Loken, B.; Lynam, A.; McCarthy, J.; Phan, C. & Rasphone, A. (2016). "Pardofelis marmorata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T16218A97164299.

- Vigors, N. A.; Horsfield, T. (1827). "Descriptions of two species of the genus Felis, in the collections of the Zoological Society". The Zoological Journal. III (11): 449–451.

- McCarthy, J.; Dahal, S.; Dhendup, T.; Gray, T. N. E.; Mukherjee, S.; Rahman, H.; Riordan, P.; Boontua, N. & Willcox, D. (2015). "Catopuma temminckii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T4038A97165437.

- Gray, J. E. (1874). "Description of a new Species of Cat (Felis badia) from Sarawak". Proceedings of the Scientific Meetings of the Zoological Society of London for the Year 1874: 322–323.

- Hearn, A.; Brodie, J.; Cheyne, S.; Loken, B.; Ross, J. & Wilting, A. (2017). "Catopuma badia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T4037A112910221.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1778). "Der Serval". Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther.

- Thiel, C. (2015). "Leptailurus serval". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T11638A50654625.

- Gray, J. E. (1843). "Felidae". List of the specimens of Mammalia in the British Museum. London: The British Museum. pp. 39–46.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1777). "Der Karakal". Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther. pp. 413–414.

- Avgan, B.; Henschel, P.; Ghoddousi, A. (2016). "Caracal caracal". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T3847A102424310.

- Temminck, C. J. (1827). "Félis doré Felis aurata". Monographies de Mammalogie. Paris: G. Dufour et E. d'Ocagne. pp. 120−121.

- Bahaa-el-din, L.; Mills, D.; Hunter, L. & Henschel, P. (2015). "Caracal aurata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T18306A50663128.

- Gray, J. E. (1842). "Descriptions of some new genera and fifty unrecorded species of Mammalia". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 10 (65): 255−267. doi:10.1080/03745484209445232.

- Molina, G. I. (1782). "La Guigna Felis guigna". Saggio sulla storia naturale del Chilli. Bologna: Stamperia di S. Tommaso d’Aquino. p. 295.

- Lucherini, M.; Eizirik, E.; de Oliveira, T.; Pereira, J.; Williams, R.S.R. (2016). "Leopardus colocolo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15309A97204446.

- Cornalia, E. (1865). "Descrizione di una nuova specie del genere Felis. Felis jacobita (Corn.)". Memorie della Societá Italiana di Scienze Naturali. 1: 3−9.

- Villalba, L.; Lucherini, M.; Walker, S.; Lagos, N.; Cossios, D.; Bennett, M. & Huaranca, J. (2016). "Leopardus jacobita". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15452A50657407.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis pardalis". Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. I (Tenth ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 42.

- Paviolo, A.; Crawshaw, P.; Caso, A.; de Oliveira, T.; Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A.; Kelly, M.; De Angelo, C. & Payan, E. (2016). "Leopardus pardalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T11509A97212355.

- Schinz, H. R. (1821). "Wiedische Katze Felis wiedii". Das Thierreich eingetheilt nach dem Bau der Thiere: als Grundlage ihrer Naturgeschichte und der vergleichenden Anatomie von dem Herrn Ritter von Cuvier. Säugethiere und Vögel, Volume 1. Stuttgart, Tübingen: Cotta. pp. 235–236.

- de Oliveira, T.; Paviolo, A.; Schipper, J.; Bianchi, R.; Payan, E. & Carvajal, S. V. (2015). "Leopardus wiedii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T11511A50654216.

- Napolitano, C.; Gálvez, N.; Bennett, M.; Acosta-Jamett, G. & Sanderson, J. (2015). "Leopardus guigna". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T15311A50657245.

- D'Orbigny, A.; Gervais, P. (1844). "Mammalogie: Nouvelle espèce de Felis". Extraits des Procès-verbaux des Séances. 9: 40−41.

- Pereira, J.; Lucherini, M. & Trigo, T. (2015). "Leopardus geoffroyi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T15310A50657011.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1778). "Die Maragua". Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther. pp. 396–397.

- Payan, E. & de Oliveira, T. (2016). "Leopardus tigrinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T54012637A50653881.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Hensel, R. (1872). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Säugethiere Süd-Brasiliens". Physikalische Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (1873): 1−130.

- Trigo, T. C.; Schneider, A.; de Oliveira, T. G.; Lehugeur, L. M.; Silveira, L.; Freitas, T. R. O.; Eizirik, E. (2013). "Molecular Data Reveal Complex Hybridization and a Cryptic Species of Neotropical Wild Cat". Current Biology. 23 (24): 2528–2533. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.046. PMID 24291091.

- de Oliveira, T.; Trigo, T.; Tortato, M.; Paviolo, A; Bianchi, R.; & Leite-Pitman, M. R. P. (2016). "Leopardus guttulus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T54010476A54010576. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T54010476A54010576.en.

- Kerr, R. (1792). "F. Lynx canadensis". The Animal Kingdom or zoological system of the celebrated Sir Charles Linnaeus. Class I. Mammalia. Edinburgh & London: A. Strahan & T. Cadell. p. 157−158.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1778). "Der Rotluchs". Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther. pp. 442–443.

- Kelly, M.; Morin, D.; & Lopez-Gonzalez, C. A. (2016). "Lynx rufus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T12521A50655874.

- Vashon, J. (2016). "Lynx canadensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T12518A101138963.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis lynx". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 43.

- Breitenmoser, U.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Lanz, T.; von Arx, M.; Antonevich, A.; Bao, W. & Avgan, B. (2015). "Lynx lynx". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T12519A121707666.

- Temminck, C. J. (1827). "Felis pardina". Monographies de mammalogie, ou description de quelques genres de mammifères, dont les espèces ont été observées dans les différens musées de l'Europe. Vol. 1. Leiden: C. C. Vander Hoek. pp. 116−117.

- Rodríguez, A. & Calzada, J. (2015). "Lynx pardinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T12520A50655794. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T12520A50655794.en.

- Brookes, J. (1828). "Section Carnivora. Order Prædacae". A catalogue of the Anatomical and Zoological Museum of Joshua Brookes. London: Richard Taylor. p. 16.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1777). "Der Gepard". Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen (Dritter Theil). Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther. pp. 392−393.

- Durant, S.; Mitchell, N.; Ipavec, A. & Groom, R. (2015). "Acinonyx jubatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T219A50649567.

- Jardine, W. (1834). "Genus II. Puma". Naturalists' library, Mammalia, volume 2. Edinburgh: Lizars, Stirling and Kenney. pp. 266–267.

- Linnaeus, C. (1771). "Felis concolor". Mantissa plantarum altera. Generum editionis VI et specierum editionis II. Regni animalis appendix. Holmiae: Laurentii Salvii. p. 522.

- Nielsen, C.; Thompson, D.; Kelly, M.; Lopez-Gonzalez, C. A. (2015). "Puma concolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T18868A97216466. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T18868A50663436.en.

- Geoffroy St. Hilaire, É. (1803). "Le Chat Yagouarundi Felis yagouarundi". Catalogue des Mammifères du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. Paris, France: Museum National d'histoire naturelle. p. 124.

- Caso, A.; de Oliveira, T.; Carvajal, S.V. (2015). "Herpailurus yagouaroundi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T9948A50653167. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T9948A50653167.en.

- Brandt J. F. (1842). "Observations sur le manoul (Felis manul Pallas)". Bulletin Scientifique. Académie Impériale des Sciences de Saint Petersbourg. 9: 37–39.

- Pallas, P. S. (1776). "Felis manul". Reise durch verschiedene Provinzen des russischen Reichs in einem ausführlichen Auszuge. Volume 3. Frankfurt und Leipzig: J. G. Fleischer. p. 490.

- Ross, S.; Barashkova, A.; Farhadinia, M. S.; Appel, A.; Riordan, P.; Sanderson, J. & Munkhtsog, B. (2016). "Otocolobus manul". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016.

- Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, I. (1831). "Le Chat à Taches de Rouille, Felis rubiginosa (Nob.)l". In Bélanger, C.; Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, I. (eds.). Voyage aux Indes-Orientales par le nord de l'Europe, les provinces du Caucases, la Géorgie, l'Arménie et la Perse, suivi des détails topographiques, statistiques et autre sur le Pégou, les Iles de Jave, de Maurice et de Bourbon, sur le Cap-de-bonne-Espérance et Sainte-Hélène, pendant les années 1825, 1826, 1827, 1828 et 1829. Tome 3: Zoologie. Paris: Arthus Bertrand. pp. 140−144.

- Mukherjee, S.; Duckworth, J. W.; Silva, A.; Appel, A. & Kittle, A. (2016). "Prionailurus rubiginosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T18149A50662471.

- Kerr, R. (1792). "Bengal Tiger-Cat Felis bengalensis". The Animal Kingdom or zoological system of the celebrated Sir Charles Linnaeus. Class I. Mammalia. Edinburgh & London: A. Strahan & T. Cadell. pp. 151–152.

- Ross, J.; Brodie, J.; Cheyne, S.; Hearn, A.; Izawa, M.; Loken, B.; Lynam, A.; McCarthy, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Phan, C.; Rasphone, A.; Wilting, A. (2015). "Prionailurus bengalensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T18146A50661611.

- Bennett, E. T. (1833). "Felis viverrinus". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. Part I: 68–69.

- Mukherjee, S.; Appel, A.; Duckworth, J. W.; Sanderson, J.; Dahal, S.; Willcox, D. H. A.; Herranz Muñoz, V.; Malla, G.; Ratnayaka, A.; Kantimahanti, M.; Thudugala, A.; Thaung R. & Rahman, H. (2016). "Prionailurus viverrinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T18150A50662615.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Wilting, A.; Brodie, J.; Cheyne, S.; Hearn, A.; Lynam, A.; Mathai, J.; McCarthy, J.; Meijaard, E.; Mohamed, A.; Ross, J.; Sunarto, S.; & Traeholt, C. (2015). "Prionailurus planiceps". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T18148A50662095.

- Desmarest, A. G. (1816). "Le Chat de Java, Felis javanensis Nob.". In Société de naturalistes et d'agriculteurs (ed.). Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine. Tome 6. Paris: Chez Deterville. p. 115.

- Patel, R. P.; Wutke, S.; Lenz, D.; Mukherjee, S.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Veron, G.; Fickel, J.; Wilting, A.; Förster, D. (2017). "Genetic Structure and Phylogeography of the Leopard Cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) Inferred from Mitochondrial Genomes". Journal of Heredity. 108 (4): 349−360. doi:10.1093/jhered/esx017. PMID 28498987.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis". Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). 1 (Tenth reformed ed.). Holmiae: Laurentii Salvii. pp. 42–44.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1778). "Der Kirmyschak". Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther. pp. 414–416.

- Gray, T. N. E.; Timmins, R. J.; Jathana, D.; Duckworth, J. W.; Baral, H. & Mukherjee, S. (2016). "Felis chaus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T8540A50651463.

- Burchell, W. J. (1824). "Felis nigripes". Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa, Vol. II. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. p. 592.

- Sliwa, A.; Wilson, B.; Küsters, M. & Tordiffe, A. (2016). "Felis nigripes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T8542A50652196.

- Loche, V. (1858). "Description d'une nouvelle espèce de Chat par M. le capitaine Loche" [Description of a new species of cat, Mr. Captain Loche]. Revue et Magasin de Zoologie Pure et Appliquée. 2. X: 49–50.

- Sliwa, A.; Ghadirian, T.; Appel, A.; Banfield, L.; Sher Shah, M. & Wacher, T. (2016). "Felis margarita". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T8541A50651884.

- Milne-Edwards, A. (1892). "Observations sur les mammifères du Thibet". Revue Générale des Sciences Pures et Appliquées. III: 670–671.

- Riordan, P.; Sanderson, J.; Bao, W.; Abdukadir, A.; Shi, K. (2015). "Felis bieti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T8539A50651398.

- Forster, G. R. (1780). "LIII. Der Karakal". Herrn von Büffons Naturgeschichte der vierfüssigen Thiere. Mit Vermehrungen, aus dem Französischen übersetzt. Sechster Band [Mr. von Büffon‘s Natural History of Quadrupeds. With additions, translated from French. Volume 6]. Berlin: Joachim Pauli. pp. 299–319.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1778). "Die wilde Kaze" [The wild Cat]. Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen (Dritter Theil). Erlangen: Expedition des Schreber'schen Säugthier- und des Esper'schen Schmetterlingswerkes. pp. 397–402.

- Yamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A.; Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. (2015). "Felis silvestris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T60354712A50652361.

- Filhol, H. (1879). "Étude sur les Mammifères fossiles de Saint-Gérand le Puy (Allier)". Annales des Sciences Géologiques. 10 (1): 1–252.

- Peigné, S. (1999). "Proailurus, l'un des plus anciens Felidae (Carnivora) 'dEurasie : systematique et evolution". Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire Naturelle de Toulouse (135): 125–134.

- Gervais, P. (1850). "Zoologie et paléontologie françaises. Nouvelles recherches sur les animaux vertébrés dont on trouve les ossements enfouis dans les sol de le France et sur leur comparaison avec les espèces propres aux autres regions du globe". Zoologie et Paléontologie Françaises. 8: 1–271.

- Barnett, R.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Soares, A. E. R.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Zazula, G.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shapiro, B.; Kirillova, I. V.; Larson, G.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2016). "Mitogenomics of the Extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), Resolve its Position within the Panthera Cats". Open Quaternary. 2: 4. doi:10.5334/oq.24.

- Leidy, J. (1853). "Description of an Extinct Species of American Lion: Felis atrox". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 10: 319–322. doi:10.2307/1005282. JSTOR 1005282.

- Kretzoi, M. (1938). "Die Raubtiere von Gombaszög nebst einer Übersicht der Gesamtfauna (Ein Beitrag zur Stratigraphie des Altquartärs)". Annales Musei Nationalis Hungarici. 31: 88–157.

- Stephens, J. J. (1959). "A new Pliocene cat from Kansas". Academy of Science, Arts and Letters (44): 41–46.

- Werdelin, L. (1981). "The evolution of lynxes" (PDF). Annales Zoologici Fennici (18): 37–71.

- Adams, D. B. (1979). "The Cheetah: Native American". Science. 205 (4411): 1155–1158. Bibcode:1979Sci...205.1155A. doi:10.1126/science.205.4411.1155. PMID 17735054. S2CID 17951039.

- Morales, J.; Pickford, M.; Soria, D.; Fraile, S. (1998). "New carnivores from the basal Middle Miocene of Arrisdrift, Namibia". Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae. 91: 27–40.

- Morales, J.; Pickford, M.; Fraile, S.; Salesa, M. J.; Soria, D. (2003). "Creodonta and Carnivora from Arrisdrift, early Middle Miocene of southern Namibia". Memoirs of the Geological Survey of Namibia. 19: 177–194.

- Werdelin, L. (2011). "A new genus and species of Felidae (Mammalia) from Rusinga Island, Kenya, with notes on early Felidae of Africa". Estudios Geológicos. 67 (2): 217–222. doi:10.3989/egeol.40463.184.

- Adrian, B.; Werdelin, L.; Grossman, A. (2018). "New Miocene Carnivora (Mammalia) from Moruorot and Kalodirr, Kenya". Palaeontologia Electronica. 21 (1): 21.1.10A. doi:10.26879/778.

- Anton, M. (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. ISBN 9780253010421.

- de Bonis, L.; Peigné, S.; Mackaye, H. T.; Likius, A.; Vignaud, P.; Brunet, M. (2018). "New sabre-toothed Felidae (Carnivora, Mammalia) in the hominid-bearing sites of Toros Menalla (late Miocene, Chad)" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 40 (1): 69−87. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2018v40a3.

- Spassov, N.; Geraads, D. (2014). "A New Felid from the Late Miocene of the Balkans and the Contents of the Genus Metailurus Zdansky, 1924 (Carnivora, Felidae)". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 22: 45–56. doi:10.1007/s10914-014-9266-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Felidae. |

- Felidae at Curlie

- Keller, E. (2015). "Secrets of the World's 38 Species of Wild Cats". National Geographic Society.

%2C_Paris%2C_d%C3%A9cembre_2013.jpg)

-8.jpg)

_female_2.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

_in_XiNing_Wild_Zoo_croped.jpg)