German Australians

German Australians (German: Deutsch-Australier) are Australian citizens of ethnic German ancestry. The German community constitute one of the largest ethnic groups in Australia, numbering 898,700 or 4.5 percent of respondents in the 2011 Census. It is the fifth most identified European ancestry in Australia behind English, Irish, Scottish and Italian.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| German 898,674 (by ancestry, 2011) 108,003 (by birth, 2011) 4.5% of total Australian population.[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| South Australia, Western Australia, New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland | |

| Languages | |

| Australian English, German, Barossa German | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Lutheranism and Roman Catholicism.[2] |

Demography

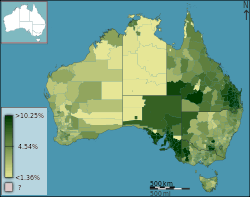

The 2011 Census counted 108,000 Australian residents who were born in Germany.[1] However, 898,700 persons identified themselves as having German ancestry, either alone or in combination with another ancestry.[1] This number does not include people of German ancestry who selected their ancestry as simply "Australian". The 2001 census recorded 103,010 German-born in Australia, although this excludes persons of German ethnicity and culture born elsewhere, such as the Netherlands (1,030), Hungary (660) and Romania (440).

In December 2001, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs estimated that there were 15,000 Australian citizens resident in Germany.[3]

According to the 2001 Census, the German-born population are more likely than Australians as a whole to live in South Australia (11.9 per cent to 7.6 per cent) and Victoria (27.0 per cent to 24.7 per cent). They are also more likely to live in rural and regional areas. It is probable their German Australian children share this settlement pattern.

According to census data released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 2004, German Australians are, by religion, 21.7 per cent Catholic, 16.5 per cent Anglican, 32.8 per cent Other Christian, 4.2 Other Religions and 24.8 No Religion.

In 2001, the German language was spoken at home by 76,400 persons in Australia. German is the eighth most widely spoken language in the country after English, Chinese, Italian, Greek, Arabic, Vietnamese, Spanish, and Tagalog.

Immigration history

| No. of arrivals July 1949 – June 2000[4] | July 1940 – June 1959[lower-alpha 1] | July 1959 – June 1970[lower-alpha 2] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 255,930 | 162,756 | 50,452 |

| Total immigrant arrivals | 5,640,638 | 1,253,083 | 1,445,356 |

| Percentage of immigrants from Germany | 4.5% | 13.0% | 3.5% |

Germans have been in Australia since the commencement of European settlement in 1788. At least seventy-three Germans arrived in Australia as convicts.[5]

1800s

Germans formed the largest non-English-speaking group in Australia up to the 20th century.[6]

Old Lutherans

Old Lutherans emigrated in response to the 1817 Prussian Union and organized churches both among themselves and with other German speakers, such as the Kavel-Fritzsche Synod.

Although a few individuals had emigrated earlier,[7] the first large group of Germans arrived in South Australia 1838, not long after the British colonisation of South Australia. These "Old Lutherans" were from Brandenburg (then a Prussian province), and were trying to preserve their traditional faith. They emigrated with the financial assistance of George Fife Angas and the Emigration Fund. Not all subsequent arrivals shared this religious motivation, but the Lutheran Church remained at the centre of the German settlers' lives right into the 20th century.[8]

Forty-Eighters

Forty-Eighters is a term for those who participated in or supported the European Revolutions of 1848. Many emigrated as a result of those revolutions. In particular, following the ultimate failure of the "March Revolution" in Germany, a substantial number of Germans immigrated to Australia. See Forty-Eighters in Australia.

Fleeing militarism

Many Germans had immigrated to Australia to flee the rise of militarism and martial chauvinism in the land of their birth. Indeed, "After the Unification of Germany under Prussia in 1870/1871, when Universal Conscription was brought in across all the States of Deutschland, the pattern of emigration from Germany to Australia changed. Instead of the earlier pattern of the majority of settlers arriving in families, young single men started to arrive, young men who were at odds with the increasing militarisation of their Fatherland, and also often at odds with the Rampant Chauvinisation of German Social Life."[9]

1900s

By 1900, Germans were the fourth-largest European ethnic group on the continent, behind the English, Irish and Scots.[10]

By 1914, the number of German-Australians (including the descendants of German-born migrants of the second and third generation who had become Australians by birth) was estimated at approximately 100,000.[11]

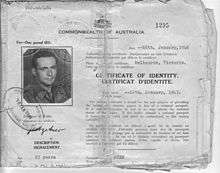

Throughout both world wars Germans were considered an "enemy within" and a number were interned or deported – or both. The persecution of German Australians also included the closure of German schools, the banning of the German language in government schools, and the renaming of many German place names. To avoid persecution and/or to demonstrate that they commit themselves to their new home, many German Australians changed their names into Anglicised or Francophone variants. During WWII, Australia was also place of incarceration of 2,542 "enemy aliens" deported from Britain, composed of many of the Austrian and German nationals who were expelled in a blanket deportation, and numerous Italian citizens.[12] Notorious for the inhumane treatment present during the voyage, the 2,053 anti-Nazis, 451 prisoners of war, and approximately 55 Nazi sympathisers and others departed from Liverpool via HMT Dunera shortly after the Fall of France in 1940.[12]

After the Second World War, Australia received a large influx of ethnic German displaced persons who were a significant proportion of Australia's post war immigrants. A number of German scientists were recruited soon after the War through the ESTEA scheme some of them coming by migrant ships such as the Partizanka.[13][14] In the 1950s and 1960s, German immigration continued under assisted migration programs promoted by the Australian Government. By July 2000, Germany was the fifth most common birthplace for settler arrivals in Australia after United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy and New Zealand.[4] By 1991, there were 112,000 German-born persons in Australia.

World War I

Internment camps

.jpg)

The internment camps were maintained by the Australian Army during World War I. At the time, they were also described as concentration camps. Old prison buildings in Berrima and Trial Bay Gaol were initially used as locations for camps in New South Wales.

The largest internment camp in WWI was the Holsworthy Internment Camp, located west of Sydney.[15] There were camps in Berrima; Bourke; Holsworthy and Trial Bay (all New South Wales); Enoggera, Queensland; Langwarrin, Victoria; the Molonglo camp at Fyshwick, Australian Capital Territory; Rottnest Island, Western Australia; and Torrens Island, South Australia. Smaller and temporary internment camps were also established on Bruny Island, Tasmania; Fort Largs, South Australia; and Garden Island, Western Australia.[16] The camp on Rottnest Island, which operated from the end of 1914 until the end of 1915, housed 989 people in September 1915. Among this group were 841 Australian and Austrian internees, as well as 148 prisoners of war.[17] According to a statement by the Australian War Memorial organisation, there were a total of 7,000 people interned over the course of World War I, including roughly 4,500 Germans and British people of German background who had already been living in Australia for a long time.[18] This meant approximately 4.5% of the German-Australian population were held in internment camps.

One of the largest internment camps for imprisoned officers and soldiers of the Imperial German Navy from the warzones in the Pacific, in China and in Southeast Asia, was the Trial Bay Gaol. Among those interned were German and Austrian business people who had been captured on ships, as well as wealthy, high-standing Germans and Austrians living in Australia who were assumed to be sympathising with the enemy. The camp was opened in August 1915 and at its peak contained as many as 580 men.[19] The internees were held in solitary cells within the prison, with the exception of those with a high social or military rank, who were kept in cabins on the bay. The prisoners were free to swim, fish, and sunbathe on the beach or play tennis in the prison yard on a court they had built themselves. In 1916 they held a theatre performance of the comedy Minna von Barnhelm by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing.[20] They had their own orchestra and in 1917 created their own newspaper named Welt am Montag (World on Monday), which was published once a week. In memory of the four Germans who died in the camp, the internees built a monument on the hill at Trial Bay. The internees were transferred in 1918 due to fears that German warships would be able to land in the bay. They were moved to the Holsworthy internment camp near Sydney, now Holsworthy Barracks.[19] After it became known that graves of the Allied forces in Germany had been vandalised, the internees' monument was destroyed. It was once again constructed in 1960 and now leads the way to the memorial site on the hill.[21]

Some Australians believed that the prisoners were being treated too well. However, they were under constant surveillance, their post was censored and contact with the outside world (as well as contact with internees from other camps) was not allowed.[19]

Many internees from Western Australia were transported to camps in New South Wales, including the 193 German marines from the SMS Emden which had been defeated by HMAS Sydney.

After the war ended, the camps were shut down and most of the occupants were deported[15], but German immigration was only made legal again in 1925. The German population increased slowly as a result and eventually came to a halt in 1933 with Adolf Hitler's rise to power.[22]

World War II

Internment

In World War I, the majority of internees were of German heritage. However, in World War II, a large number of Italians and Japanese were also imprisoned. The internees, which included women and children, had come from more than 30 different countries, including Finland, Hungary, Portugal and also the Soviet Union. In addition to the Australian residents who were imprisoned, there were also people of German and Japanese descent who were captured overseas and brought to Australia. These people came from England, Palestine, Iran, present-day Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. The first of these groups arrived on the HMT Dunera from England in 1940[23] and their destination was the Hay Internment Camp in New South Wales.

The internment camps in WWII were constructed for three reasons: residents could not be allowed to support Australia's enemies, the public needed to be placated, and those who had been captured overseas and transported to Australia had to be housed somewhere. All Japanese people were immediately imprisoned, but it was only after the war criminals of Nazi Germany and Italy were discovered that Germans and Italians were sent to the internment camps. This was especially true for those living in northern Australia, because that was where the enemy was expected to invade. More than 20 percent of Italians in Australia were held in internment camps as well as a total of 7,000 people with connections to the enemy, 1,500 of which who were British nationals. 8,000 people from overseas were detained in Australian camps and in 1942, the camps were at their largest, with a total of 12,000 internees in the country. In addition to British people of German origin, Australian fascists could not escape imprisonment: leading members of the Australia First Movement were interned, including Adela Pankhurst and P. R. Stephensen.[24]

Tourism

Australia has long been a popular destination for German tourists and students.[25]

Education

There are the following German international schools in Australia:

German Australian culture

The Australian wine industry was the creation of German settlers in the nineteenth century.[26]

The Goethe-Institut is active in Australia, there are branches in Melbourne and Sydney.[27]

Media

Historically, German newspapers were set up by early settlers, with many being forced to close or merge due to labour shortages caused by the Victorian gold rush of the 1850s-1860s. A number of the earliest South Australian newspapers were printed primarily in German, and these included:

- Die Deutsche Post für die Australischen Colonien (1848–1850) – Adelaide: Australia's first non-English newspaper[28]

- Suedaustralische Zeitung (1850–1851) – Adelaide

- Deutsche Zeitung für Süd-Australien (1851) – Tanunda

- Adelaider Deutsche Zeitung (1851–1862) – Adelaide: this was also the first German language newspaper to publish an entertainment supplement - Blatter fur Ernst und scherz.[29]

- Süd Australische Zeitung (1860–1874) – Tanunda/Adelaide

- Australisches Unterhaltungsblatt (1862–1916) – Tanunda: a supplement to the Süd Australische Zeitung and Australische Zeitung

- Tanunda Deutsche Zeitung (1863–1869) – Tanunda; later renamed Australische Deutsche Zeitung

- Australische Deutsche Zeitung (1870–1874) – Tanunda/Adelaide: a Melbourne edition of the newspaper was also printed 1870–1872.

- Neue Deutsche Zeitung (1875–1876) – Adelaide: opposition newspaper to Australische Zeitung

- Australische Zeitung (1875–1916) – Tanunda/Adelaide: formed by the merger of Süd Australische Zeitung, and Australische Deutsche Zeitung; closed due to WWI

- Australische Zeitung (1927–1929) – Tanunda: attempted revival

- Adelaider Post (1960–1962) – Adelaide: South Australian edition of the Sydney-based Die Woche in Australien.

- Neue Australische Post (1984–1993), Salisbury

German missionaries

There were many German missionaries who emigrated to Australia, established mission stations and worked with Aboriginal Australians, in some cases helping to preserve their languages and culture.[30]

- 1838: Rev. Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann (1815–1893) and Christian Gottlob Teichelmann (1807–1893) established and ran the Pirltawardli (or Piltawodli) Native Location in Adelaide from 1838 to 1845, learning the local Kaurna language, teaching the Kaurna in their own language and translating texts. Later Samuel Klose joined them. Their work provided the basis for a language revival in the 21st century, after the language was all but extinct.[31]

- 1892: Carl Strehlow was an anthropologist, linguist and genealogist who served on two Lutheran missions, Killalpaninna Mission (also known as Bethesda) in northern South Australia from 1892, and then, from October 1894, Hermannsburg, Northern Territory (also known as Finke River), renowned for its artists, with his wife Frieda Strehlow. They were the parents of noted anthropologist Ted Strehlow.[32]

- 1901: German Pallotine missionaries took over the running of the mission station at Beagle Bay Mission in Western Australia.[33]

- La Grange Mission at Bidyadanga (1955/6–1985), was run by Thomas Bachmair (1872–1918). Considered an "enlightened" mission, there was a strong emphasis on enculturation and respect for traditional customs and obligations.[34]

Missions founded by Germans

- Killalpaninna Mission (1866 – 1915): Founded by Johann Friedrich Gößling and Ernst Homann, and two lay brethren, Hermann Vogelsang and Ernst Jakob; later joined by Strehlow.

- Hermannsburg, Northern Territory (1877 – 1982?): Founded by A. Hermann Kemp (sometimes spelt Kempe) and Wilhelm F. Schwarz of the Hermannsburg Mission in Germany.

- Aurukun Mission (1904 – 1913), originally Archer River Mission Station, Queensland: Founded by Moravians Rev. Arthur Richter and his wife Elisabeth[35]

- Bathurst Island Mission (1911 – 1978), founded by Francis Xavier Gsell[36]

- La Grange Mission at Bidyadanga (1955/6–1985)

Notable Australians of German ancestry

| Name | Born | Description | Connection to Australia | Connection to Germany |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eric Abetz | 1958 | Australian Senator | Immigrated to Australia from Germany in 1961 | Born in Germany |

| Eric Bana | 1968 | Australian Actor | Born in Australia | German mother |

| Gerard Brennan | 1928 | Judge and retired Chief Justice of Australia (1995–1998) | Born in Australia | German maternal ancestry |

| Bettina Arndt | 1949 | Sexologist and critic of feminism | Born in the United Kingdom | German father |

| Heinz Arndt | 1915 | Economist | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Shaun Berrigan | 1978 | Rugby League player | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Henry Bolte | 1908 | Politician (Premier of Victoria) | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Dieter Brummer | 1976 | Soap opera actor | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Ernest Burgmann | 1885 | Anglican bishop and social justice activist | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Meredith Burgmann | 1947 | Politician (Australian Labor Party) | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Wolfgang Degenhardt | 1924 | Artist | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Carl Ditterich | 1945 | Australian rules footballer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Andrew Ettingshausen | 1965 | Rugby League player | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Brad Fittler | 1972 | Rugby League player | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Harry Frei | 1951 | Cricketer | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Johannes Fritzsch | 1960 | Conductor | Works and lives in Australia | Born in Germany |

| Gotthard Fritzsche | 1797 | Lutheran pastor | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Ken Grenda | Businessman and philanthropist | Born in Australia | German ancestry | |

| Michael Grenda | 1964 | Olympic cyclist | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Andre Haermeyer | 1956 | Politician (Australian Labor Party) | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Heinrich Haussler | 1984 | Cyclist | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| George Heinz | 1891 | Australian rules footballer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Hans Heysen | 1877 | Landscape artist | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Ben Hilfenhaus | 1983 | Cricketer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Bert Hinkler | 1892 | Aviator | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Hermann Homburg | 1874 | Politician | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| August Kavel | 1798 | Lutheran pastor | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Kristina Keneally | 1968 | Politician (Premier of New South Wales) | Immigrated to Australian from the United States | German ancestry |

| David Klemmer | 1993 | Rugby league player | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| David Koch | 1956 | Television presenter | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Gerard Krefft | 1830 | Zoologist and palaeontologist | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Sonia Kruger | 1965 | Television presenter, media personality and dancer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Dichen Lachman | 1982 | Actress and producer | Raised in Adelaide, Australia | Born in Kathmandu, Nepal, to a German-Australian father |

| Ludwig Leichhardt | 1813 | Explorer | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Darren Lehmann | 1970 | Cricketer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Carl Linger | 1810 | Composer | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Stewart Loewe | 1968 | Australian rules footballer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Baz Luhrmann | 1962 | Film director, screenwriter, producer, and actor | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Bertha McNamara | 1853 | Socialist and feminist | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| John Monash | 1865 | Australian General | Born in Australia | German (Jewish) Parents |

| Ferdinand von Mueller | 1825 | Botanist, geologist and physician | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| David Neitz | 1975 | Australian rules footballer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Nadine Neumann | 1975 | Olympic swimmer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Hubert Opperman | 1904 | Cyclist and politician | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Annastacia Palaszczuk | 1969 | 39th Premier of Queensland | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Arthur Phillip | 1738 | First Governor of New South Wales | Served in NSW 1788–1792 | German father |

| Ingo Rademacher | 1971 | Soap opera actor | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Jack Riewoldt | 1988 | Australian rules footballer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Nick Riewoldt | 1982 | Australian rules footballer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Hermann Sasse | 1895 | Lutheran theologian | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Chris Schacht | 1946 | Politician (Australian Labor Party) and mining company director | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Manfred Schäfer | 1943 | Football (soccer) player | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Jessicah Schipper | 1986 | Olympic swimmer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Melanie Schlanger | 1986 | Olympic swimmer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Mark Schwarzer | 1972 | Football (soccer) player | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Emily Seebohm | 1992 | Olympic swimmer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Anthony Seibold | 1974 | Rugby league coach | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Gert Sellheim | 1901 | Artist | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Lithuania to ethnically-German parents |

| Wolfgang Sievers | 1913 | Photographer | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Christian Sprenger | 1985 | Olympic swimmer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Carl Strehlow | 1871 | Lutheran missionary | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Ted Strehlow | 1908 | Anthropologist | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Matthias Ungemach | 1968 | Olympic rower | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Shane Warne | 1969 | Cricketer | Born in Australia | German mother |

| Chris Watson | 1867 | Prime Minister of Australia | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Chile to ethnically-German father |

| Shane Webcke | 1974 | Rugby League player | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

| Judith Zeidler | 1968 | Olympic rower | Immigrated to Australia | Born in Germany |

| Markus Zusak | 1975 | Writer | Born in Australia | German ancestry |

See also

- German settlement in Australia

- Temple Society Australia

- Forty-Eighters

- Barossa German

- Australian place names changed from German names

- Lutheran Church of Australia

- History of the Lutheran Church of Australia

- Goethe-Institut

Notes

- Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs: Settler arrivals by birthplace data not available prior to 1959. For the period July 1949 to June 1959, Permanent and Long Term Arrivals by Country of Last Residence have been included as a proxy for this data. When interpreting this data for some countries, in the period immediately after World War II, there were large numbers of displaced persons whose country of last residence was not necessarily the same as their birthplace.

- Note this period covers 11 years rather than a decade.

References

- "Reflecting a Nation: Stories from the 2011 Census, 2012–2013". 2011 Census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 21 June 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2013. Total count of persons: 19,855,288.

- "Welcome to the Department of Home Affairs". www.immi.gov.au. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Estimates of Australian Citizens Living Overseas as at December 2001" (PDF). Southern Cross Group (DFAT data). 14 February 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- "Immigration: Federation to Century's End 1901–2000" (PDF). Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs. October 2001. p. 25. Archived from the original (pdf, 64 pages) on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- Donohoe, J.H. (1988) The Forgotten Australians: Non-Anglo or Celtic Convicts and Exiles.

- G. Leitner, Australia's Many Voices: Australian English – The National Language, 2004, p. 181

- "09/06/1837-16/10/1837: Solway [Hamburg to Nepean Bay]". Passengers in History. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Harmstorf, Ian (5 June 2015). "Germans". Adelaidia. "First published in The Wakefield companion to South Australian history, edited by Wilfrid Prest, Kerrie Round and Carol Fort (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2001). Edited lightly and references updated". Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Knoll, Wayne D. (4 May 2011). "GERMAN-AUSTRALIAN ALIENS OF MILITARISM: The Anti-War German-Australian Story". Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- Harmstorf & Cigler 1985, p. .

- Kay Saunders, Roger Daniels, Alien Justice: Wartime Internment in Australia and North America, p. 4

- "Wartime internment". naa.gov.au. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Homeyer, Uta v. (1994). "The Employment of Scientific and Technical Enemy Aliens (Estea) Scheme in Australia: A Reparation for World War Ii?". Prometheus. 12: 77–93. doi:10.1080/08109029408629379.

- Muenstermann, Ingrid (30 May 2015). Some Personal Stories of German Immigration to Australia since 1945. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781503503137.

- "Wartime internment camps in Australia". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "World War I internment camps". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "Military Functions – Rottnest Island Authority". Rottnest Island. 2005. Archived from the original on 21 August 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Civilian internees in Australia". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- "Trial Bay, South West Rocks Detention Barracks 1914–1918 [Germany]". Auspostal History. 2016. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Trial Bay, New South Wales". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Arakoon State Recreation Area Plan of Management" (PDF). NSW Environment, Energy and Science. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Tampke, Jurgen (2008). "Germans". The Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- The compete passenger list can be retrieved at RecordSearch | National Archives of Australia using the search term "Dunera". It is also possible to search using passenger names.

- "Wartime internment camps in Australia". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "Welcome to the Australian Embassy, Berlin". www.germany.embassy.gov.au. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Speech By The Prime Minister, The Hon PJ Keating, Mp Luncheon The His Excellency Dr Von Weizsaecrer, President Of The Federal Republic Of Germany Parliament House, Canberra, 6 September 1993 Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Goethe-Institut Australien". www.goethe.de. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- Laube, Anthony. "LibGuides: SA Newspapers: C-E". guides.slsa.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Laube, Anthony. "LibGuides: SA Newspapers: A-B". guides.slsa.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Ganter, Regina (2009–2018). "A web-directory of intercultural encounters". German Missionaries in Australia. Griffith University. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- Amery, Robert. "Piltawodli Native Location (1838–1845)". German Missionaries in Australia. Griffith University. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- Scherer, Paul E. (2004). "Strehlow, Carl Friedrich Theodor (1871–1922)". webjournals.ac.edu.au. Evangelical History Association of Australia. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015.

- "Beagle Bay (1890–2000)". German missionaries in Australia. Griffith University. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

Also known as: Nôtre Dame du Sacré Coeur (1890-1901), Sacred Heart Mission, Herz Jesu Mission.

- "La Grange Mission (Bidyadanga) (1924–1985)". German missionaries in Australia. Griffith University. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "Aurukun (1904–1913))". German missionaries in Australia. Griffith University. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "Bathurst Island Mission 1911-1938-1978)". German missionaries in Australia. Griffith University. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

Sources

- Harmstorf, Ian; Cigler, Michael (1985). The Germans in Australia. Australian ethnic heritage series. Melbourne: AE Press. ISBN 0-86787-203-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Lehmann, Hartmut. "South Australian German Lutherans in the second half of the nineteenth century: A case of rejected assimilation?." Journal of Intercultural Studies 2.2 (1981): 24–42. online

- Lehmann, Hartmut. "Conflicting kinds of loyalty: The political outlook of the australischer christenbote, Melbourne, 1867–1910." Journal of Intercultural Studies 6.2 (1985): 5–21.

- Petersson, Irmtraud. German Images in Australian Literature from the 1940s to the 1980s (P. Lang, 1990)

- Seitz, Anne, and Lois Foster. "Dilemmas of immigration—Australian expectations, migrant responses: Germans in Melbourne." Journal of Sociology 21.3 (1985): 414–430. online

- Tolley, Julie Holbrook. "A social and cultural investigation of women in the wine industry of South Australia" (thesis, 2004) online

External links

- Zivil Lager (Internment Camp): World War One Prisoners Of War At Trial Bay (online exhibition)

- The Enemy At Home: German Internees in World War One Australia (online exhibition)

- Interview with Sophie Schütt about South Australian Documentary (in German)

- South Australia on German TV – article about Sophie Schütt travel documentary

- German Australian Aliens of Militarism

- German missionaries in Australia

- Jurgen Tampke – University of New South Wales (2008). "Germans". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 4 October 2015. (Germans in Sydney)