Batavia (1628 ship)

Batavia ([baːˈtaːviaː] (![]()

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Namesake: | Batavia, Dutch East Indies |

| Owner: | Dutch East India Company |

| Completed: | 1628 |

| Maiden voyage: | 29 October 1628 |

| On board: | 341 heads |

| Wrecked: | 4 June 1629 |

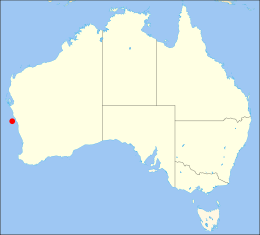

| Location: | Wallabi Group, Houtman Abrolhos |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | East Indiaman |

| Tonnage: | 650 tons |

| Displacement: | 1,200 tons |

| Length: | 56.6 meters (186 feet) |

| Beam: | 10.5 meters (34 feet) |

| Height: | 55 meters (180 feet) |

| Draught: | 5.1 meters (17 feet) |

| Sail plan: | Full-rigged |

| Sail area: | 3,100 m2 (33,000 sq ft) |

| Speed: | 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph) |

| Armament: | 24 × cast-iron cannon |

On 4 June 1629, the Batavia wrecked on the Houtman Abrolhos, a chain of small islands off the coast of Western Australia. As the ship broke apart, 40 of the 341 passengers drowned in their attempts to reach land. The ship's commander, Francisco Pelsaert, sailed to Batavia to get help, leaving merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz in charge. Cornelisz sent about 20 men to nearby islands under the false pretense of searching for fresh water, abandoning them there to die. He then orchestrated a mutiny that, over course of several weeks, resulted in the murder of approximately 125 of the remaining survivors, including women, children and infants; a small number of women were kept as sexual slaves, among them the famed beauty Lucretia Jans, reserved by Cornelisz for himself.[1]

Meanwhile, the men sent away had unexpectedly found water and, after learning of the atrocities, waged battles with the mutineers under soldier Wiebbe Hayes' leadership. In October, at the height of their last and deadliest battle, they were interrupted by the return of Pelsaert aboard the Sardam. He subsequently tried and convicted Cornelisz and six of his men, who became the first Europeans to be legally executed in Australia. Two other mutineers, convicted of comparatively minor crimes, were marooned on mainland Australia, thus becoming the first Europeans to permanently inhabit the Australian continent. Of the original 332 people on board Batavia, only 122 made it to the port of Batavia.

Associated today with "one of the worst horror stories in maritime history", Batavia has been the subject of numerous published histories, the earliest dating from 1647. Due to its unique place in the history of European contact with Australia, the story of the Batavia is sometimes offered as an alternative founding myth to the landing of British convicts in Sydney. Many Batavia artefacts, including the ship's stern and skeletal remains from the massacre, are housed at the Shipwreck Galleries in Fremantle, Western Australia, while a replica of the ship is moored as a museum ship in Lelystad.

Maiden voyage

On 27 October 1628, the newly built Batavia, commissioned by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), sailed from Texel in the Netherlands[2] for the Dutch East Indies, to obtain spices. It sailed under commander and senior merchant Francisco Pelsaert, with Ariaen Jacobsz serving as skipper. Pelsaert and Jacobsz had previously encountered each other in Dutch Suratte, when Pelsaert publicly dressed-down Jacobsz after he became drunk and insulted Pelsaert in front of other merchants. Animosity existed between the two men after this incident.[3] Also on board was the junior merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz (30), a bankrupt apothecary from Haarlem who was fleeing the Netherlands, in fear of arrest because of his heretical beliefs associated with the painter Johannes van der Beeck, also known as Torrentius.

Mutiny

During the voyage, Jacobsz and Cornelisz conceived a plan to take the ship, which would allow them to start a new life elsewhere, using the huge supply of trade gold and silver on board.[4] After leaving the Cape of Good Hope, where they had stopped for supplies, Jacobsz deliberately steered the ship off course, and away from the rest of the fleet. Jacobsz and Cornelisz had already gathered a small group of men around them and arranged an incident from which the mutiny was to ensue. This involved sexually assaulting a high-ranking young female passenger, Lucretia Jans, in order to provoke Pelsaert into disciplining the crew. They hoped to paint his discipline as unfair and recruit more members out of sympathy. However, the woman was able to identify her attackers.[5][6]

Shipwreck

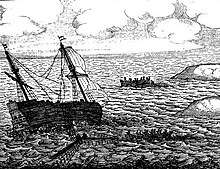

On 4 June 1629, Batavia struck Morning Reef near Beacon Island, part of the Houtman Abrolhos off the Western Australian coast.[2] Of the 322 aboard, most of the passengers and crew managed to get ashore, although 40 people drowned. The survivors, including all the women and children, were then transferred to nearby islands in the ship's longboat and yawl.

An initial survey of the islands found no fresh water and only limited food (sea lions and birds). Pelsaert realised the dire situation and decided to search for water on the mainland. A group consisting of Jacobsz, Pelsaert, senior officers, a few crew members, and some passengers left the wreck site in a nine-metre (30 ft) longboat, in search of drinking water. After an unsuccessful search for water on the mainland, they left the other survivors and headed north in a danger-fraught voyage to the city of Batavia, Dutch East Indies, to seek rescue.

En route the crew made further forays onto the mainland in search of fresh water. In his journal, Pelsaert stated that on 15 June 1629, they sailed through a channel between a reef and the coast, finding an opening around midday at a latitude guessed to be about 23 degrees south where they were able to land, and water was found.

The group spent the night on land. Pelsaert commented on the vast number of termite mounds in the vicinity and the plague of flies that afflicted them. Pelsaert stated that they continued north with the intention of finding the "river of Jacob Remmessens", identified first in 1622, but owing to the wind were unable to land. Drake-Brockman has suggested that this location is to be identified with Yardie Creek.[7][8][9]

It was not until the longboat reached the island of Nusa Kambangan in the Dutch East Indies that Pelsaert and the others found more water.[10] The journey took 33 days, with everyone surviving. After their arrival in Batavia, the boatswain, Jan Evertsz, was arrested and executed for negligence and "outrageous behavior" before the loss of the ship (he was suspected to have been involved). Jacobsz was also arrested for negligence, although his position in the potential mutiny was not guessed by Pelsaert.[11]

Governor-General Jan Pieterszoon Coen immediately gave Pelsaert command of Sardam to rescue the other survivors, as well as to attempt to salvage riches from Batavia's wreck. Pelsaert returned to the vicinity of ocean where the mishap occurred within a month, but it took another month of searching to locate the islands again. He finally arrived at the site only to discover that a bloody massacre had taken place among the survivors, reducing their numbers by at least a hundred.[12]

Murders

Cornelisz was one of a few men who stayed on Batavia to pillage and steal. He was one of the few who survived the final break-up of the ship and made it to the island after floating for two days. Cornelisz was elected to be in charge of the survivors due to his high rank. He made plans to hijack any rescue ship that might return and use the vessel to seek another safe haven. Cornelisz made far-fetched plans to start a new kingdom, using the gold and silver from the wreck. However, to carry out this plan, he first needed to eliminate possible opponents.[13]

Cornelisz's first deliberate act was to have all weapons and food supplies commandeered and placed under his control. He then moved a group of soldiers, led by Wiebbe Hayes, to nearby West Wallabi Island, under the false pretense of searching for water. They were told to light signal fires when they found water and they would then be rescued.[13] Convinced that they would be unsuccessful, he then left them there to die, taking complete control of the remaining survivors.

Cornelisz never committed any of the murders himself, although he tried and failed to poison a baby (who was eventually strangled).[14] Instead, he coerced others into doing it for him, usually under the pretense that the victim had committed a crime such as theft. The mutineers had originally murdered to save themselves, but eventually they began to kill for pleasure or out of habit.[15] Cornelisz planned to reduce the island's population to around 45 so that their supplies would last as long as possible. He also feared that many of the survivors remained loyal to the VOC.[16] In total, Cornelisz' followers murdered at least 110 men, women, and children.

Rescue

Although Cornelisz had left the soldiers, led by Hayes, to die, they had in fact found good sources of water and food on their islands. Initially, they were unaware of the barbarity taking place on the other islands and sent pre-arranged smoke signals announcing their finds. However, they soon learned of the massacres from survivors fleeing Cornelisz' island. In response, the soldiers devised makeshift weapons from materials washed up from the wreck. They also set a watch so that they were ready for the mutineers, and built a small fort out of limestone and coral blocks.[17]

Cornelisz seized on the news of water on the other island, as his own supply was dwindling and the continued survival of the soldiers threatened his own success. He went with his men to try to defeat the soldiers marooned on West Wallabi Island. However, the trained soldiers were by now much better fed than the mutineers and easily defeated them in several battles, eventually taking Cornelisz hostage. The mutineers who escaped regrouped under soldier Wouter Loos and tried again, this time employing muskets to besiege Hayes' fort and almost defeating the soldiers.[18]

But Hayes' men prevailed again, just as Pelsaert arrived. A race to the rescue ship ensued between Cornelisz' men and the soldiers. Hayes reached the ship first and was able to present his side of the story to Pelsaert. After a short battle, the combined force captured all of the mutineers.[19]

Aftermath

Pelsaert decided to conduct a trial on the islands, because Sardam on the return voyage to Batavia would have been overcrowded with both survivors and prisoners. After a brief trial, the worst offenders were taken to Seal Island and executed. Cornelisz and several of the major mutineers had both hands chopped off before being hanged.[20]

Loos and a cabin boy, Jan Pelgrom de Bye, considered only minor offenders, were marooned on mainland Australia, never to be heard of again. This unwittingly made them the first Europeans to have permanently lived on the Australian continent.[21] This location is now thought to be Wittecarra Creek near Kalbarri, though another suggestion is nearby Port Gregory.[10]

The remaining mutineers were taken to Batavia for trial. Five were hanged, while several others were flogged, keelhauled or dropped from the yardarm on the later voyage back home.[22] Cornelisz' second in command, Jacop Pietersz, was broken on the wheel, the most severe punishment available at the time. Jacobsz, despite being tortured, did not confess to his part in planning the mutiny and escaped execution due to lack of evidence. What finally became of him is unknown. It is suspected that he died in prison in Batavia. A board of inquiry decided that Pelsaert had exercised a lack of authority and was therefore partly responsible for what had happened. His financial assets were seized, and he died within a year.

Hayes was hailed a hero and promoted to sergeant, which increased his salary, while those who had been under his command were promoted to the rank of corporal.[22] Of the original 332 people on board Batavia, only 122 made it to the port of Batavia.[23] Sardam eventually sailed home with most of the treasure previously housed on the Batavia aboard. Of the twelve treasure chests that were originally on board, ten were recovered and taken aboard Sardam.[21]

Wreck

Surveying the north-west coast of the Abrolhos Islands for the British Admiralty in April 1840, Captain John Lort Stokes reported that "the beams of a large vessel were discovered", assumed to be Zeewijk, "on the south west point of an island", reminding them that since Zeewijk's crew "reported having seen a wreck of a ship on this part, there is little doubt that the remains were those of the Batavia".[20]

In the 1950s, historian Henrietta Drake-Brockman argued from extensive archival research, that the Batavia wreck must lie in the Wallabi Group of islands. The wreck was first sighted in 1963 by lobster fisherman David Johnson. Many artifacts were salvaged in the 1970s, including port-side stern timbers, cannons and an anchor.[24] To facilitate the monitoring and any future treatment, the hull timbers were erected on a steel frame. Its design—and that of a stone arch, also recovered—was such that individual components could be easily removed.[25]

In 1972, the Dutch government transferred rights to Dutch shipwrecks in Australian waters to the Australian government. Excavated items are on display at the Western Australian Museum's various locations, though the majority of cannons and anchors have been left in situ. The wreck remains one of the premier diving sites on the Western Australian coast.[26]

Treasure

Batavia carried a considerable amount of treasure. Each ship in the Batavia class carried an estimated 250,000 guilders in twelve wooden chests, each containing about 8,000 silver coins.[27] This money was intended for the purchase of spices and other commodities in Java. The bulk of these coins were silver rijksdaalder produced by the individual Dutch states, with the remainder being mostly made up of similar coins produced by German cities such as Hamburg.

Pelsaert was instructed to recover as much of the money as possible on his return to the Abrolhos Islands, using divers "to try if it is possible to salvage all the money [and] the casket of jewels that before your departure was already saved on the small island".[28] Recovery of the money was far from easy. Pelsaert reported difficulties in pulling up heavy chests, e.g. 27 October 1629, when a chest had to be marked with a buoy for later recovery. On 9 November, he recorded sending four money chests to Sardam, and three the next day, but then abandoned further recovery work. By 13 November, Pelsaert recorded that ten money chests had been recovered—about 80,000 coins—leaving two lost since there had been twelve loaded originally. One was jammed under a cannon, and one had been broken open by the mutineers.[29]

Batavia's treasure also included special items being carried by Pelsaert for sale to the Mogul Court in India where he had intended to travel on to. There were four jewel bags, stated to be worth about 60,000 guilders, and an early-fourth-century Roman cameo, as well as numerous other items either now displayed in Fremantle and Geraldton, Western Australia, or recovered by Pelsaert.[30]

Legacy

A Batavia ship replica was built from 1985 to 1995, using the same materials and methods utilized in the early 17th century. Its design was based on contemporary accounts, recovered wreckage, and other contemporary ships such as Vasa. After a number of commemorative voyages, the vessel is now moored as a museum ship in Lelystad.

Media

In 1973, Bruce Beresford produced a film about the ship called The Wreck Of The Batavia.[31][32] Another documentary film, The Batavia – Wreck, Mutiny and Murder, was aired on the Nine Network in 1995.[33] In 2012, Peter Fitzsimons released a book called Batavia discussing the mutiny in detail and in 2017, a 60 Minutes report detailed the archaeological recovery of the skeletal remains of some of the victims.[34] Casefile True Crime Podcast also covered the incident in detail in February 2020.

References

- Batavia (1629): giving voice to the voiceless – Symposium (PDF) (booklet). Nedlands: University of Western Australia. 7 October 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "Batavia". Department of Maritime Archaeology Online Databases. Western Australian Museum. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- Dash 2002, p. 57.

- Dash 2002, p. 87.

- Dash 2002, p. 99.

- "VOC ship Batavia". Voc.iinet.net.au. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Drake-Brockman 2006, pp. 300–304.

- Godard 1993, p. 156.

- Dash 2002, p. 150.

- Godard 1993, pp. 186–187.

- Dash 2002, pp. 161–162.

- Dash 2002, p. 162.

- "Batavia's Graveyard". Houtman Albrolhos. Perth: VOC Historical Society. 2008. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- Dash 2002, p. 140.

- Dash 2002, p. 138.

- Dash 2002, p. 122.

- Dash 2002, pp. 176–179.

- Dash 2002, pp. 182–183.

- Dash 2002, pp. 188–190.

- Kimberly, W.B. (compiler) (1897). History of West Australia. A Narrative of her Past. Together With Biographies of Her Leading Men. Melbourne: F.W. Niven. p. 10.

- Leavesley, James H. (2003). "The 'Batavia', an apothecary, his mutiny and its vengeance" (PDF). Vesalius. IX (2): 22–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Batavia's History". Western Australian Museum. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- Ariese, Csilla. (2012). Databases of the people aboard the VOC ships Batavia (1629) & Zeewijk (1725) : an analysis of the potential for finding the Dutch castaways' human remains in Australia. Australian National Centre of Excellence for Maritime Archaeology. Fremantle, W.A.: Australian National Centre of Excellence for Maritime Archaeology. p. 5. ISBN 9781876465070. OCLC 811789103.

- Green, J. (1989). The loss of the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie retourschip Batavia. British Archaeological Reports. 489. Oxford: BAR Publishing.

- Richards, V. (2002). "Cosmetic treatment of deacidified Batavia timbers". AICCM Bulletin. Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material. 27: 12–13. doi:10.1179/bac.2002.27.1.003.

- Souter, C. (2006). "Cultural Tourism and Diver Education". Maritime Archaeology. The Springer Series in Underwater Archaeology. Boston: Springer: 163–176. doi:10.1007/0-387-26108-7_13. ISBN 978-0-387-25882-9.

- Dash 2002, p. 55.

- Drake-Brockman 2006, pp. 257–258.

- Drake-Brockman 2006, pp. 218–220.

- "Defining Moments Wreck of the Batavia". https://www.nma.gov.au. National Museum Australia. 15 June 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020. External link in

|website=(help) - The Wreck of the Batavia (TV Movie 1973) - IMDb, retrieved 1 March 2020

- The Wreck Of The Batavia (1973), retrieved 1 March 2020

- The Batavia: Wreck, Mutiny and Murder (1995) - IMDb, retrieved 1 March 2020

- A mutiny, psychopath and mass murder – investigating 388-year-old cold case | 60 Minutes Australia, retrieved 1 March 2020

Bibliography

- Dash, M. (2002). Batavia's Graveyard. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9780575070240.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drake-Brockman, H. (2006). Voyage to Disaster. Perth: UWA Press. ISBN 9781920694722.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, H. (2000). Island of Angry Ghosts: The Story of the Batavia. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780732266066.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Godard, P. (1993). The First and Last Voyage of the Batavia. Perth: Abrolhos Publishing. ISBN 9780646105192.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Batavia. |

- Works about the Batavia at Open Library

- Works about the Batavia at WorldCat Identities