Heard Island and McDonald Islands

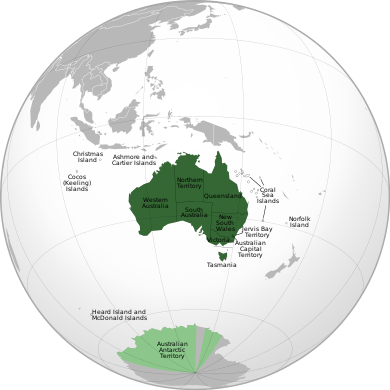

The Territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands[1][2] (HIMI[3]) is an Australian external territory comprising a volcanic group of mostly barren Antarctic islands, about two-thirds of the way from Madagascar to Antarctica. The group's overall size is 372 km2 (144 sq mi) in area and it has 101.9 km (63 mi) of coastline. Discovered in the mid-19th century, the islands have been an Australian territory since 1947 and contain the country's two only active volcanoes. The summit of one, Mawson Peak, is higher than any mountain on the Australian mainland. The islands lie on the Kerguelen Plateau in the Indian Ocean.

Satellite image of the southern tip of Heard Island. Cape Arkona is seen on the left side of the image, with Lied Glacier just above and Gotley Glacier just below. Big Ben Volcano and Mawson Peak are seen at the lower right side of the image. | |

.svg.png) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Indian Ocean |

| Major islands | 2 |

| Area | 368 km2 (142 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 2,745 m (9,006 ft) |

| Highest point | Mawson Peak |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | Uninhabited (2011) |

| Criteria | Natural: viii, ix |

| Reference | 577 |

| Inscription | 1997 (21st session) |

| Area | 658,903 ha |

The islands are among the most remote places on Earth: They are located approximately 4,099 km (2,547 mi) southwest of Perth,[4] 3,845 km (2,389 mi) southwest of Cape Leeuwin, Australia, 4,200 km (2,600 mi) southeast of South Africa, 3,830 km (2,380 mi) southeast of Madagascar, 1,630 km (1,010 mi) north of Antarctica, and 450 km (280 mi) southeast of the Kerguelen Islands.[5] The islands are currently uninhabited.

Geography

Heard Island, by far the largest of the group, is a 368-square-kilometre (142 sq mi) mountainous island covered by 41 glaciers[6] (the island is 80% covered with ice[1]) and dominated by the Big Ben massif. It has a maximum elevation of 2,745 metres (9,006 ft) at Mawson Peak, the historically active volcanic summit of Big Ben. A July 2000 satellite image from the University of Hawaii's Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) Thermal Alert Team showed an active 2-kilometre-long (1.2 mi) and 50- to 90-metre-wide (164–295 ft) lava flow trending south-west from the summit of Big Ben.[7]

The much smaller and rocky McDonald Islands are located 44 kilometres (27 mi) to the west of Heard Island. They consist of McDonald Island (186 metres (610 ft) high), Flat Island (55 metres (180 ft) high) and Meyer Rock (170 metres (560 ft) high). They total approximately 2.5 square kilometres (1.0 sq mi) in area, where McDonald Island is 1.13 square kilometres (0.4 sq mi). There is a small group of islets and rocks about 10 kilometres (6 mi) north of Heard Island, consisting of Shag Islet, Sail Rock, Morgan Island and Black Rock. They total about 1.1 square kilometres (0.4 sq mi) in area.

Mawson Peak and McDonald Island are the only two active volcanoes in Australian territory. Mawson Peak is also one of the highest Australian mountains (higher than Mount Kosciuszko); surpassed only by Mount McClintock range in the Antarctic territory.[8] Mawson Peak has erupted several times in the last decade; the most recent eruption was filmed on 2 February 2016.[9] The volcano on McDonald Island, after being dormant for 75,000 years, became active in 1992 and has erupted several times since, the most recent in 2005.[10]

Heard Island and the McDonald Islands have no ports or harbours; ships must anchor offshore. The coastline is 101.9 kilometres (63.3 mi), and a 12-nautical-mile (22 km; 14 mi) territorial sea and 200-nautical-mile (370 km; 230 mi) exclusive fishing zone are claimed.[1]

Wetlands

Heard Island has a number of small wetland sites scattered around its coastal perimeter, including areas of wetland vegetation, lagoons or lagoon complexes, rocky shores and sandy shores, including the Elephant Spit. Many of these wetland areas are separated by active glaciers. There are also several short glacier-fed streams and glacial pools. Some wetland areas have been recorded on McDonald Island but, due to substantial volcanic activity since the last landing was made in 1980, their present extent is unknown.

The HIMI wetland is listed on the Directory of Important Wetlands in Australia and, in a recent analysis of Commonwealth-managed wetlands, was ranked highest for nomination under the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar Convention) as an internationally important wetland.

Six wetland types have been identified from HIMI covering approximately 1860 ha: coastal ‘pool complex’ (237 ha); inland ‘pool complex’ (105 ha); vegetated seeps mostly on recent glaciated areas (18 ha); glacial lagoons (1103 ha); non-glacial lagoons (97ha); Elephant Spit (300 ha) plus some coastal areas. On Heard Island, the majority of these types suites are found below 150 m asl. The wetland vegetation occurs in the ‘wet mixed herbfield’ and ‘coastal biotic vegetation’ communities described above.

The wetlands provide important breeding and feeding habitat for a number of Antarctic and subantarctic wetland animals. These include the southern elephant seal and macaroni, gentoo, king and southern rockhopper penguins, considered to be wetland species under the Ramsar Convention. Non-wetland vegetated parts of the islands also support penguin and other seabird colonies.

Climate

The islands have an Antarctic climate, tempered by their maritime setting. The weather is marked by low seasonal and daily temperature ranges, persistent and generally low cloud cover, frequent precipitation and strong winds. Snowfall occurs throughout the year. Monthly average temperatures at Atlas Cove (at the northwestern end of Heard Island) range from 0.0 to 4.2 °C (32.0 to 39.6 °F), with an average daily range of 3.7 to 5.2 °C (38.7 to 41.4 °F) in summer and −0.8 to 0.3 °C (30.6 to 32.5 °F) in winter. The winds are predominantly westerly and persistently strong. At Atlas Cove, monthly average wind speeds range between around 26 and 33.5 km/h (16.2 and 20.8 mph). Gusts in excess of 180 km/h (110 mph) have been recorded. Annual precipitation at sea level on Heard Island is in the order of 1,300 to 1,900 mm (51.2 to 74.8 in); rain or snow falls on about 3 out of 4 days.[11]

Meteorological records at Heard Island are incomplete.

| Climate data for Heard Island, 12 m asl (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.1 (68.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.4 (59.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

5.3 (41.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

5.4 (41.7) |

4.2 (39.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

2.2 (36.0) |

0.9 (33.6) |

0.5 (32.9) |

0.4 (32.7) |

0.5 (32.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

3.1 (37.6) |

2.8 (37.0) |

1.9 (35.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

0.8 (33.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −0.5 (31.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

| Source 1: Météo climat stats[12] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Météo Climat [13] | |||||||||||||

Wildlife

Flora

Constraints

The islands are part of the Southern Indian Ocean Islands tundra ecoregion that includes several subantarctic islands. In this cold climate plant life is mainly limited to grasses, lichens, and mosses.[14] Low plant diversity reflects the islands’ isolation, small size, severe climate, the short, cool growing season and, for Heard Island, substantial permanent ice cover. The main environmental determinants of vegetation on subantarctic islands are wind exposure, water availability, parent soil composition, salt spray exposure, nutrient availability, disturbance by trampling (from seabirds and seals) and, possibly, altitude. At Heard Island, exposure to salt spray and the presence of breeding and moulting seabirds and seals are particularly strong influences on vegetation composition and structure in coastal areas.

History

Evidence from microfossil records indicates that ferns and woody plants were present on Heard Island during the Tertiary (a period with a cool and moist climate). Neither group of plants is present today, although potential Tertiary survivors include the vascular plant Pringlea antiscorbutica and six moss species. Volcanic activity has altered the distribution and abundance of the vegetation. The vascular flora covers a range of environments and, although only six species are currently widespread, glacial retreat and the consequent connection of previously separate ice-free areas is providing opportunities for further distribution of vegetation into adjacent areas.

Flowering plants and ferns

Low-growing herbaceous flowering plants and bryophytes are the major vegetation components. The vascular flora comprises the smallest number of species of any major subantarctic island group, reflecting its isolation, small ice-free area and severe climate. Twelve vascular species are known from Heard Island, of which five have also been recorded on McDonald Island. None of the vascular species is endemic, although Pringlea antiscorbutica, Colobanthus kerguelensis, and Poa kerguelensis occur only on subantarctic islands in the southern Indian Ocean.

The plants are typically subantarctic, but with a higher abundance of the cushion-forming Azorella selago than other subantarctic islands. Heard Island is the largest subantarctic island with no confirmed human-introduced plants. Areas available for plant colonisation on Heard Island are generally the result of retreating glaciers or new ice-free land created by lava flows. Today, substantial vegetation covers over 20 km2 of Heard Island, and is best developed on coastal areas at elevations below 250 m.

Mosses and liverworts

Bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) contribute substantially to the overall biodiversity of Heard Island, with 43 mosses and 19 liverworts being recorded, often occupying habitats unsuitable for vascular plants, such as cliff faces. Bryophytes are present in most of the major vegetation communities including several soil and moss-inhabiting species. A 1980 survey of McDonald Island found lower diversity than that on Heard Island; four mosses and a number of algal species are recorded from there.

Algae

At least 100 species of terrestrial algae are known from Heard Island, commonly in permanently moist and ephemeral habitats. Forests of the giant Antarctic kelp Durvillaea antarctica occur at a number of sites around Heard Island and at least 17 other species of seaweed are known, with more to be added following the identification of recent collections. Low seaweed diversity is due to the island's isolation from other land masses, unsuitable beach habitat, constant abrasion by waves, tides and small stones, and the extension of glaciers into the sea in many areas.

Vegetation communities

Heard Island has a range of terrestrial environments in which vegetation occurs. Seven general vegetation communities are currently recognised, although vegetation composition is considered more of a continuum than discrete units:

- Subantarctic vegetation is minimal and includes small types of shrubbery, including mosses and liverworts.

- Open cushionfield vegetation is the most widespread and abundant vegetation type on Heard Island. It is characterised by Azorella selago cushions interspersed with bryophytes, small vascular species and bare ground with 20–75% cover, and found mainly at altitudes between 30–70m asl.

- Fellfield describes vegetation with abundant bare ground and less than 50% plant cover. Fellfield may occur as a result of harsh climatic and/or edaphic factors, or recent deglaciation which has exposed bare ground.

- Mossy fellfield is a community with high species richness and consists of bryophytes and small Azorella selago cushions. It is found at altitudes between 30–150 m in areas with intermediate exposure.

- Wet mixed herbfield occurs on moist substrate, mostly on moraines and moist lee slopes (often in association with burrowing petrels colonies) at low altitude (< 40 m) where the water table is at or close to the surface. Species richness is highest here of all the communities, with dominant species being Poa cookii, Azorella selago, Pringlea antiscorbutica, Acaena magellanica, and Deschampsia antarctica.

- Coastal biotic vegetation is dominated by Poa cookii and Azorella selago, occurring mainly on coastal sites of moderate exposure and in areas subject to significant influence from seals and seabirds.

- Saltspray vegetation is dominated by the salt-tolerant moss Muelleriella crassifolia and limited in extent, being found at low elevations on lavas in exposed coastal sites.

- Closed cushionfield is found on moraines and sand at altitudes mostly below 60 m, and is dominated almost entirely by Azorella selago cushions that often grow together to form continuous carpets which can be subject to burrowing by seabirds.

Outlook

One of the most rapidly changing physical settings in the subantarctic has been produced on Heard Island by a combination of rapid glacial recession and climate warming. The consequent increase in habitat available for plant colonisation, plus the coalescing of previously discrete ice-free areas, has led to marked changes in the vegetation of Heard Island in the last 20 years or so. Other species and vegetation communities found on subantarctic islands north of the Antarctic Convergence now absent from the Heard Island flora may colonise the island if climate change produces more favourable conditions.

Some plant species are spreading and modifying the structure and composition of communities, some of which are also increasing in distribution. It is likely that further changes will occur, and possibly at an accelerated rate. Changes in population numbers of seal and seabird species are also expected to affect the vegetation by changing nutrient availability and disturbance through trampling.[15]

One plant species on Heard Island, Poa annua, a cosmopolitan grass native to Europe, was possibly introduced by humans, though is more likely to have arrived naturally, probably by skuas from the Kerguelen Islands where it is widespread. It was initially recorded in 1987 in two deglaciated areas of Heard Island not previously exposed to human visitors, while being absent from known sites of past human habitation. Since 1987 Poa annua populations have increased in density and abundance within the original areas and have expanded beyond them. Expeditioner boot traffic during the Australian Antarctic program expedition in 1987 may be at least partly responsible for the spread, but it is probably mainly due to dispersal by wind and the movement of seabirds and seals around the island.

The potential for introducing plant species (including invasive species not previously found on subantarctic islands) by both natural and human-induced means is high. This is due to the combination of low species diversity and climatic amelioration. During the 2003/04 summer a new plant species, Cotula plumosa, was recorded. Only one small specimen was found growing on a coastal river terrace that had experienced substantial development and expansion of vegetation over the past decade. The species has a circumantarctic distribution and occurs on many subantarctic islands.[16]

Fungi

71 species of lichens have been recorded from Heard Island and they are common on exposed rock, dominating the vegetation in some areas.[17] As with plants, a 1980 survey of McDonald Island found lower diversity there, with just eight lichen species and a number of non-lichenized fungi recorded.

Fauna

The main indigenous animals are insects along with large populations of ocean-going seabirds, seals and penguins.[18]

Mammals

Sealing at Heard Island lasted from 1855 to 1910, during which time 67 sealing vessels are recorded visiting, nine of which were wrecked off the coast.[19] Relics that survive from that time include trypots, casks, hut ruins, graves and inscriptions. This caused the seal populations there to either become locally extinct or reduced to levels too low to exploit economically. Modern sealers visited from Cape Town in the 1920s.[20] Since then the populations have generally increased and are protected. Seals breeding on Heard include the southern elephant seal, the Antarctic fur seal and the subantarctic fur seal. Leopard seals visit regularly in winter to haul-out though they do not breed on the islands. Crabeater, Ross and Weddell seals are occasional visitors.[21]

Birds

Heard Island and the McDonald Islands are free from introduced predators and provide crucial breeding habitat in the middle of the vast Southern Ocean for a range of birds. The surrounding waters are important feeding areas for birds and some scavenging species also derive sustenance from their cohabitants on the islands. The islands have been identified by BirdLife International as an Important Bird Area because they support very large numbers of nesting seabirds.[22]

Nineteen species of birds have been recorded as breeding on Heard Island[23] and the McDonald Islands, although recent volcanic activity at the McDonald Islands in the last decade is likely to have reduced vegetated and un-vegetated nesting areas.[24]

Penguins are by far the most abundant birds on the islands, with four breeding species present, comprising king, gentoo, macaroni and eastern rockhopper penguins. The penguins mostly colonise the coastal tussock and grasslands of Heard Island, and have previously been recorded as occupying the flats and gullies on McDonald Island.

Other seabirds recorded as breeding at Heard Island include three species of albatross (wandering, black-browed and light-mantled albatrosses, southern giant petrels, Cape petrels, four species of burrowing petrels Antarctic and Fulmar prions, common and South Georgian diving-petrels), Wilson's storm-petrels, kelp gulls, subantarctic skuas, Antarctic terns and the Heard shag.[25] Although not a true seabird, the Heard Island subspecies of the black-faced sheathbill also breeds on the island. Both the shag and the sheathbill are endemic to Heard Island.

A further 28 seabird species are recorded as either non-breeding visitors or have been noted during 'at-sea surveys' of the islands. All recorded breeding species, other than the Heard Island sheathbill, are listed marine species under the Australian Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Act (1999, four are listed as threatened species and five are listed migratory species. Under the EPBC Act a recovery plan has been made for albatrosses and giant petrels, which calls for ongoing population monitoring of the species found at HIMI, and at the time of preparing this plan a draft recovery plan has also been made for the Heard Island cormorant (or shag) and Antarctic tern.

The recorded populations of some seabird species found in the Reserve have shown marked change. The king penguin population is the best studied seabird species on Heard Island and has shown a dramatic increase since first recorded in 1947/48, with the population doubling every five years or so for more than 50 years.

A paper reviewing population data for the black-browed albatross between 1947 and 2000/01 suggested that the breeding population had increased to approximately three times that present in the late 1940s,[26] although a Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources CCAMLR) Working Group was cautious about the interpretation of the increasing trend given the disparate nature of the data,[27] as discussed in the paper. The discovery of a large, previously unknown, colony of Heard shags in 2000/01 at Cape Pillar raised the known breeding population from 200 pairs to over 1000 pairs.[24] The breeding population of southern giant petrels decreased by more than 50% between the early 1950s and the late 1980s.

Terrestrial, freshwater and coastal invertebrates

Heard Island supports a relatively low number of terrestrial invertebrate species compared to other Southern Ocean islands, in parallel with the low species richness in the flora–that is, the island's isolation and limited ice-free area. Endemism is also generally low and the invertebrate fauna is exceptionally pristine with few, if any, (successful) human-induced introductions of alien species. Two species, including the thrips Apterothrips apteris and the mite Tyrophagus putrescentiae are thought to be recent, possibly natural, introductions. An exotic species of earthworm Dendrodrilus rubidus was also collected in 1929 from a dump near Atlas Cove, and has recently been collected from a variety of habitats including wallows, streams and lakes on Heard Island.

The arthropods of Heard Island are comparatively well known with 54 species of mite and tick, one spider and eight springtails recorded. A study over summer at Atlas Cove in 1987/88 showed overall densities of up to 60 000 individual springtails per square metre in soil under stands of Pringlea antiscorbutica. Despite a few recent surveys, the non-arthropod invertebrate fauna of Heard Island remain poorly known.

Beetles and flies dominate Heard Island's known insect fauna, which comprises up to 21 species of ectoparasite (associated with birds and seals) and up to 13 free-living species. Approximately half of the free-living insects are habitat-specific, while the remainder are generalists found in a variety of habitats, being associated with either supralittoral or intertidal zones, Poa cookii and Pringlea antiscorbutica stands, bryophytes, lichen-covered rocks, exposed rock faces or the underside of rocks. There is a pronounced seasonality to the insect fauna, with densities in winter months dropping to a small percentage (between 0.75%) of the summer maximum. Distinct differences in relative abundances of species between habitats has also been shown, including a negative relationship between altitude and body size for Heard Island weevils.

The fauna of the freshwater pools, lakes, streams and mires found in the coastal areas of Heard Island are broadly similar to those on other subantarctic islands of the southern Indian Ocean. Many species reported from Heard Island are found elsewhere. Some sampling of freshwater fauna has been undertaken during recent expeditions and records to date indicate that the freshwater fauna includes a species of Protista, a gastrotrich, two species of tardigrade, at least four species of nematode, 26 species of rotifer, six species of annelid and 14 species of arthropod.

As with the other shore biota, the marine macro-invertebrate fauna of Heard Island is similar in composition and local distribution to other subantarctic islands, although relatively little is known about the Heard Island communities compared with the well-studied fauna of some other islands in the subantarctic region, such as Macquarie and Kerguelen.

Despite Heard Island's isolation, species richness is considered to be moderate, rather than depauperate, although the number of endemic species reported is low. The large macro-alga Durvillaea antarctica supports a diverse array of invertebrate taxa and may play an important role in transporting some of this fauna to Heard Island.

The rocky shores of Heard Island exhibit a clear demarcation between fauna of the lower kelp holdfast zone and the upper shore zone community, probably due to effects of desiccation, predation and freezing in the higher areas. The limpet Nacella kerguelensis is abundant in the lower part of the shore, being found on rock surfaces and on kelp holdfasts. Other common but less abundant species in this habitat include the chiton Hemiarthrum setulosum and the starfish Anasterias mawsoni. The amphipod Hyale sp. and the isopod Cassidinopsis sp. are closely associated with the kelp. Above the kelp holdfast zone, the littornid Laevilitorina (Corneolitorina) heardensis and the bivalve mollusc Kidderia bicolor are found in well-sheltered situations, and another bivalve Gaimardia trapesina trapesina has been recorded from immediately above the holdfast zone. Oligochaetes are also abundant in areas supporting porous and spongy layers of algal mat.

History

Neither island-cluster had recorded visitors until the mid-1850s.

An American sailor, John Heard, on the ship Oriental, sighted Heard Island on 25 November 1853, en route from Boston to Melbourne. He reported the discovery one month later and had the island named after him. William McDonald aboard the Samarang discovered the nearby McDonald Islands six weeks later, on 4 January 1854.[29]

No landing took place on the islands until March 1855, when sealers from the Corinthian, led by Erasmus Darwin Rogers, went ashore at a place called Oil Barrel Point. In the sailing period from 1855 to 1880 a number of American sealers spent a year or more on the island, living in appalling conditions in dark smelly huts, also at Oil Barrel Point. At its peak the community consisted of 200 people. By 1880, sealers had wiped out most of the seal population and then left the island. In all the islands furnished more than 100,000 barrels of elephant-seal oil during this period.

A number of wrecks have occurred in the vicinity of the islands. There is also a discarded building left from John Heard's sealing station which is situated near Atlas Cove.

The first recorded landing on McDonald Island was made by Australian scientists Grahame Budd and Hugh Thelander on 12 February 1971, using a helicopter.[30][31]

The islands have been a territory of Australia since 1947, when they were transferred from the UK.[1] The archipelago became a World Heritage Site in 1997.

There were at least five private expeditions to Heard Island between 1965 and 2000. Several amateur radio operators have visited Heard, often associated with scientific expeditions. The first activity there was in 1947 by Alan Campbell-Drury. Two amateur radio DXpeditions to the island took place in 1983 using the callsigns VK0HI (the Anaconda expedition)[32] and VK0JS and VK0NL (the Cheynes II expedition), with a further operation in January 1997 (VK0IR). The recent DXpedition in March 2016 (VK0EK) was organised by Cordell Expeditions,[33] and made over 75,000 radio contacts.

Mawson Peak atop Big Ben was first climbed on 25 January 1965 by five members of the Southern Indian Ocean Expedition to Heard Island (sometimes referred to as the Patanela expedition).[34] The second ascent was made by five members of the Heard Island Expedition 1983 (sometimes referred to as the Anaconda expedition).[32] A helicopter landing was made at the summit by an ANARE team on 21 Dec 1986. An Australian Army team were successful in making the third ascent in 2000.

In 1991, the islands were the location for the Heard Island feasibility test, an experiment in very long-distance transmission of low frequency sound through the ocean.[35] The US Navy vessels MV Cory Chouest and Amy Chouest were used to transmit signals which could be detected as far away as both ocean coasts of the US and Canada.[36] The Cory Chouest was chosen because of its central moon pool and because it was already equipped with an array of low frequency transmitters. A phase-modulated 57 Hz signal was used. The experiment was successful and demonstrated that such sound waves could travel as far as the antipodes. Planned transmissions had been for ten days, although owing to the bad weather conditions and the high failure rate of the transmitter elements, used at a frequency below their design frequency, the transmissions were terminated on the sixth day, when only two of the original ten transducers were still working.

Retreat of Heard Island glaciers

Heard Island is a heavily glacierized, subantarctic volcanic island located in the Southern Ocean, roughly 4000 kilometers southwest of Australia. 80% of the island is covered in ice, with glaciers descending from 2400 meters to sea level.[37] Due to the steep topography of Heard Island, most of its glaciers are relatively thin (averaging only about 55 meters in depth).[38] The presence of glaciers on Heard Island provides an excellent opportunity to measure the rate of glacial retreat as an indicator of climate change.[39]

Available records show no apparent change in glacier mass balance between 1874 and 1929. Between 1949 and 1954, marked changes were observed to have occurred in the ice formations above 5000 feet on the southwestern slopes of Big Ben, possibly as a result of volcanic activity. By 1963, major recession was obvious below 2000 feet on almost all glaciers, and minor recession was evident as high as 5000 feet.[40]

The coastal ice cliffs of Brown and Stephenson Glaciers, which in 1954 were over 50 feet high, had disappeared by 1963 when the glaciers terminated as much as 100 yards inland.[40] Baudissin Glacier on the north coast, and Vahsel Glacier on the west coast have lost at least 100 and 200 vertical feet of ice, respectively.[40] Winston Glacier, which retreated approximately one mile between 1947 and 1963, appears to be a very sensitive indicator of glacier change on the island. The young moraines flanking Winston Lagoon show that Winston Glacier has lost at least 300 vertical feet of ice within a recent time period.[40] Jacka Glacier on the east coast of Laurens Peninsula has also demonstrated marked recession since 1955.[40]

Retreat of glacier fronts across Heard Island is evident when comparing aerial photographs taken in December 1947 with those taken on a return visit in early 1980.[37][41] Retreat of Heard Island glaciers is most dramatic on the eastern section of the island, where the termini of former tidewater glaciers are now located inland.[37] Glaciers on the northern and western coasts have narrowed significantly, while the area of glaciers and ice caps on Laurens Peninsula have shrunk by 30% - 65%.[37][38]

During the time period between 1947 and 1988, the total area of Heard Island's glaciers decreased by 11%, from 288 km2 (roughly 79% of the total area of Heard Island) to only 257 km2.[38] A visit to the island in the spring of 2000 found that the Stephenson, Brown and Baudissin glaciers, among others, had retreated even further.[38][41] The terminus of Brown Glacier has retreated approximately 1.1 kilometres since 1950.[39] The total ice-covered area of Brown Glacier is estimated to have decreased by roughly 29% between 1947 and 2004.[41] This degree of loss of glacier mass is consistent with the measured increase in temperature of +0.9 °C over that time span.[41]

Possible causes of glacier recession on Heard Island include:

- Volcanic activity

- Southward movement of the Antarctic Convergence: such a movement conceivably might cause glacier retreat through a rise in sea and air temperatures

- Climatic change

The Australian Antarctic Division conducted an expedition to Heard Island during the austral summer of 2003–04. A small team of scientists spent two months on the island, conducting studies on avian and terrestrial biology and glaciology. Glaciologists conducted further research on the Brown Glacier, in an effort to determine whether glacial retreat is rapid or punctuated. Using a portable echo sounder, the team took measurements of the volume of the glacier. Monitoring of climatic conditions continued, with an emphasis on the impact of Foehn winds on glacier mass balance.[42] Based on the findings of that expedition, the rate of loss of glacier ice on Heard Island appears to be accelerating. Between 2000 and 2003, repeat GPS surface surveys revealed that the rate of loss of ice in both the ablation zone and the accumulation zone of Brown Glacier was more than double average rate measured from 1947 to 2003. The increase in the rate of ice loss suggests that the glaciers of Heard Island are reacting to ongoing climate change, rather than approaching dynamic equilibrium.[41] The retreat of Heard Island's glaciers is expected to continue for the foreseeable future.[37]

Administration and economy

_(6173425701).jpg)

The United Kingdom formally established its claim to Heard Island in 1910, marked by the raising of the Union Flag and the erection of a beacon by Captain Evensen, master of the Mangoro. Effective government, administration and control of Heard Island and the McDonald Islands was transferred to the Australian government on 26 December 1947 at the commencement of the first Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition (ANARE) to Heard Island, with a formal declaration that took place at Atlas Cove. The transfer was confirmed by an exchange of letters between the two governments on 19 December 1950.

The islands are a territory (Territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands) of Australia administered from Hobart by the Australian Antarctic Division of the Australian Department of the Environment and Energy. The administration of the territory is established in the Heard Island and McDonald Islands Act 1953, which places it under the laws of the Australian Capital Territory and the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory.[43] The islands are contained within a 65,000-square-kilometre (25,000 sq mi) marine reserve and are primarily visited for research, meaning that there is no permanent human habitation.[1]

From 1947 until 1955 there were camps of visiting scientists on Heard Island (at Atlas Cove in the northwest, which was in 1969 again occupied by American scientists and expanded in 1971 by French scientists) and in 1971 on McDonald Island (at Williams Bay). Later expeditions used a temporary base at Spit Bay in the east, such as in 1988, 1992–93 and 2004–05.

The islands' only natural resource is fish; the Australian government allows limited fishing in the surrounding waters.[1] Despite the lack of population, the islands have been assigned the country code HM in ISO 3166-1 (ISO 3166-2:HM) and therefore the Internet top-level domain .hm. The time zone of the islands is UTC+5.[44]

See also

- Australian Antarctic Territory

- Birds of Heard and McDonald Islands

- List of glaciers in the Antarctic

- List of islands of Australia

- List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

- Retreat of glaciers since 1850

References

- "Heard Island and McDonald Islands". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- UNESCO. "Heard and McDonald Islands". Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- Commonwealth of Australia. "About Heard Island – Human Activities". Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- "Cocky Flies, Geoscience Australia". Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- "Distance Between Cities Places On Map Distance Calculator". distancefromto.net. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Ken Green and Eric Woehler (2006). Heard Island: Southern Ocean Sentinel. Surrey Beatty & Sons. pp. 28–51.

- Heard Island Geology Archived 12 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Highest Mountains". Geoscience Australia. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Rare glimpse of erupting Australian sub-Antarctic volcano. BBC News, 2 February 2016

- Volcanic activity at McDonald Island -- Heard Island. Australian Department of the Environment, Australian Antarctic Division, updated 1 March 2005

- HIMI official website.

- "Moyennes 1961-1990 Australie (Ile Heard)" (in French). Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- "Météo Climat stats for Ile Heard". Météo Climat. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- Plants. Australian Department of the Environment, Australian Antarctic Division. Updated 28 February 2005.

- Environment. "Heard Island and McDonald Islands Marine Reserve Management Plan 2005". www.legislation.gov.au. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Turner, P. A. M.; Scott, J. J.; Rozefelds, A. C. (February 2006). "Probable long distance dispersal of Leptinella plumosa Hook.f. to Heard Island: habitat, status and discussion of its arrival". Polar Biology. 29 (3): 160–168. doi:10.1007/s00300-005-0035-z. ISSN 0722-4060.

- Part 3: A Description of the Heard Island and McDonald Islands Marine Reserve. Heard Island and McDonald Islands Marine Reserve Management Plan. retrieved 5 February 2016.

- "Southern Indian Ocean Islands tundra". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- R.K.Headland (Ed.) Historical Antarctic Sealing Industry, Scott Polar Research Institute (University of Cambridge), 2018, p.167. ISBN 978-0-901021-26-7

- Headland, p.167

- "Seals". Heard Island and McDonald Islands: Seals. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Australia. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- BirdLife International. (2011). Important Bird Areas factsheet: Heard and McDonald Islands. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 2011-12-23.

- Woehler, E.J. & Croxall, J.P. 1991. ‘Status and conservation of the seabirds of Heard Island and the McDonald Islands’, in Seabird – status and conservation: a supplement, ICBP Technical Publication 11. International Council for Bird Preservation, Cambridge. pp 263–277.

- Woehler, E.J. (2006). ‘Status and trends of the seabirds of Heard Island, 2000’, in Heard Island: Southern Ocean Sentinel. ed. Green, K. & Woehler, E. Surrey Beattie.

- Woehler, E.J. (2006) ‘Status and trends of the seabirds of Heard Island, 2000’, in Heard Island: Southern Ocean Sentinel. ed. Green, K. & Woehler, E.(Surrey Beattie.

- Woehler, E. J.; Auman, H. J.; Riddle, M. J. (2002). "Long-term population increase of black-browed albatrosses Thalassarche melanophrys at Heard Island, 1947/1948–2000/2001". Polar Biology. 25 (12): 921–927. doi:10.1007/s00300-002-0436-1.

- SC–CAMLR 2002. Report of the Working Group on Fish Stock Assessment. Report of the Twenty-First Meeting of the Scientific Committee for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, Hobart, Australia.

- Goode, George Brown (1887) Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1887).

- Mills, William James (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia. ISBN 9781576074220.

- Cerchi, Dan (1 August 2009). "SIOE 2002: Heard I. & The McDonald Is". www.cerchi.net. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012.

- "Gazetteer - AADC Name Details - Australian Antarctic Data Centre". Australian Antarctic Data Centre. Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- Thornton, Meg (1983). Heard Island Expedition. Spirit of Adventure Pty Ltd. pp. 28–29. ISBN 0959256806.

- "Heard Island VK0EK DXpedition Team Has Arrived, Operation Hours Away". American Radio Relay League. 22 March 2016.

- Temple, Phillip (1966). The Sea and the Snow. Cassell Australia.

- "The Heard Island Feasibility Test". University of Washington. 2007.

- "Heard Island Feasibility Test - reception map". University of Washington. 2007.

- Ian F. Allison & Peter L. Keage (1986). "Recent changes in the glaciers of Heard Island". Polar Record. 23 (144): 255–272. doi:10.1017/S0032247400007099.

- Andrew Ruddell (25 May 2010). "Our subantarctic glaciers: why are they retreating?". Glaciology Program, Antarctic CRC and AAD. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- "'Big brother' monitors glacial retreat in the sub-Antarctic". Kingston, Tasmania, Australia: Australian Antarctic Division. 8 October 2008. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- G.M. Budd; P.J. Stephenson (1970). "Recent glacier retreat on Heard Island" (PDF). International Association for Scientific Hydrology. 86: 449–458. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- Douglas E. Thost; Martin Truffer (February 2008). "Glacier Recession on Heard Island, Southern Indian Ocean". Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research. 40 (1): 199–214. doi:10.1657/1523-0430(06-084)[THOST]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI). "Australian Research Expeditions". Kingston, Tasmania, Australia: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Antarctic Division, Territories, Environment and Treaties Section. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- "Heard Island and McDonald Islands Act 1953". Federal Register of Legislation. Australian Government. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- "Heard Island and McDonald Islands :: Time Zones". timegenie.com. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

Further reading

- Commonwealth of Australia (2014). Heard Island and McDonald Islands Marine Reserve Management Plan 2014–2024, Department of the Environment, Canberra. ISBN 978-1876934-255. Available at http://heardisland.antarctica.gov.au/

- Australian Government. (2005) Heard Island and McDonald Islands Marine Reserve Management Plan. Australian Antarctic Division: Kingston (Tas). ISBN 1-876934-08-5.

- Green, Ken and Woehler Eric (eds). (2006) Heard Island: Southern Ocean Sentinel. Chipping Norton: Surrey Beatty and Sons. ISBN 9780949324986.

- Scholes, Arthur. (1949) Fourteen men; story of the Australian Antarctic Expedition to Heard Island. Melbourne: F.W. Cheshire.

- Smith, Jeremy. (1986) Specks in the Southern Ocean. Armidale: University of New England Press. ISBN 0-85834-615-X.

- LeMasurier, W. E. and Thomson, J. W. (eds.). (1990) Volcanoes of the Antarctic Plate and Southern Oceans. American Geophysical Union. ISBN 0-87590-172-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heard Island and McDonald Islands. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Heard Island and McDonald Islands. |

- Heard Island and McDonald Islands official website

- Map of Heard Island and McDonald Islands, including all major topographical features

- World heritage listing for Heard Island and McDonald Islands

- "Heard Island and McDonald Islands". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Heard Island and McDonald Islands at Curlie

- Image gallery of Heard Island and McDonald Island with high quality limited copyright images.

- MODIS satellite image, taken 30 September 2004 and showing a von Kármán vortex street in the clouds, caused by Mawson Peak's effect on the wind

- UNESCO World Heritage site entry

- Fan's page at the Wayback Machine (archived 17 March 2006) with further historical and geographic information and a map

- Heard Island: The Cordell Expedition 2016