Antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice, or discrimination against Jews.[1][2][3] A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is generally considered to be a form of racism.[4][5]

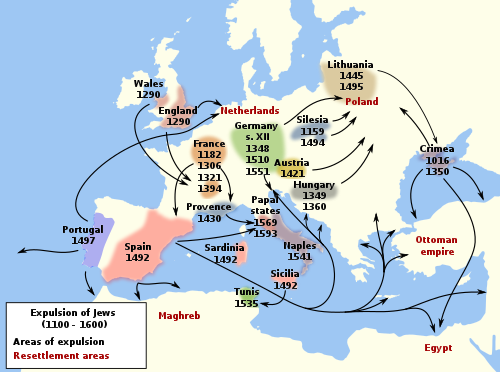

Antisemitism may be manifested in many ways, ranging from expressions of hatred of or discrimination against individual Jews to organized pogroms by mobs, state police, or even military attacks on entire Jewish communities. Although the term did not come into common usage until the 19th century, it is also applied to previous and later anti-Jewish incidents. Notable instances of persecution include the Rhineland massacres preceding the First Crusade in 1096, the Edict of Expulsion from England in 1290, the 1348–1351 persecution of Jews during the Black Death, the massacres of Spanish Jews in 1391, the persecutions of the Spanish Inquisition, the expulsion from Spain in 1492, the Cossack massacres in Ukraine from 1648 to 1657, various anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire between 1821 and 1906, the 1894–1906 Dreyfus affair in France, the Holocaust in German-occupied Europe during World War II, Soviet anti-Jewish policies, and Arab and Muslim involvement in the Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries.

The root word Semite gives the false impression that antisemitism is directed against all Semitic people, e.g., including Arabs, Assyrians and Arameans. The compound word Antisemitismus ("antisemitism") was first used in print in Germany in 1879[6] as a scientific-sounding term for Judenhass ("Jew-hatred"),[7][8][9][10][11][12] and this has been its common use since then.[13][7][14]

Origin and usage

Etymology

The origin of "antisemitic" terminologies is found in the responses of Moritz Steinschneider to the views of Ernest Renan. As Alex Bein writes: "The compound anti-Semitism appears to have been used first by Steinschneider, who challenged Renan on account of his 'anti-Semitic prejudices' [i.e., his derogation of the "Semites" as a race]."[15] Avner Falk similarly writes: "The German word antisemitisch was first used in 1860 by the Austrian Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider (1816–1907) in the phrase antisemitische Vorurteile (antisemitic prejudices). Steinschneider used this phrase to characterise the French philosopher Ernest Renan's false ideas about how 'Semitic races' were inferior to 'Aryan races'".[16]

Pseudoscientific theories concerning race, civilization, and "progress" had become quite widespread in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, especially as Prussian nationalistic historian Heinrich von Treitschke did much to promote this form of racism. He coined the phrase "the Jews are our misfortune" which would later be widely used by Nazis.[17] According to Avner Falk, Treitschke uses the term "Semitic" almost synonymously with "Jewish", in contrast to Renan's use of it to refer to a whole range of peoples,[18] based generally on linguistic criteria.[19]

According to Jonathan M. Hess, the term was originally used by its authors to "stress the radical difference between their own 'antisemitism' and earlier forms of antagonism toward Jews and Judaism."[20]

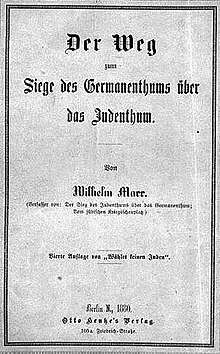

In 1879 German journalist Wilhelm Marr published a pamphlet, Der Sieg des Judenthums über das Germanenthum. Vom nicht confessionellen Standpunkt aus betrachtet (The Victory of the Jewish Spirit over the Germanic Spirit. Observed from a non-religious perspective) in which he used the word Semitismus interchangeably with the word Judentum to denote both "Jewry" (the Jews as a collective) and "jewishness" (the quality of being Jewish, or the Jewish spirit).[21][22][23]

This use of Semitismus was followed by a coining of "Antisemitismus" which was used to indicate opposition to the Jews as a people and opposition to the Jewish spirit, which Marr interpreted as infiltrating German culture. His next pamphlet, Der Weg zum Siege des Germanenthums über das Judenthum (The Way to Victory of the Germanic Spirit over the Jewish Spirit, 1880), presents a development of Marr's ideas further and may present the first published use of the German word Antisemitismus, "antisemitism".

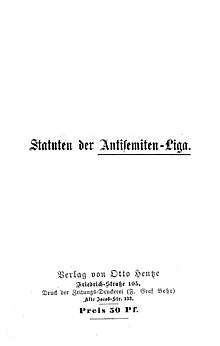

The pamphlet became very popular, and in the same year he founded the Antisemiten-Liga (League of Antisemites),[24] apparently named to follow the "Anti-Kanzler-Liga" (Anti-Chancellor League).[25] The league was the first German organization committed specifically to combating the alleged threat to Germany and German culture posed by the Jews and their influence, and advocating their forced removal from the country.

So far as can be ascertained, the word was first widely printed in 1881, when Marr published Zwanglose Antisemitische Hefte, and Wilhelm Scherer used the term Antisemiten in the January issue of Neue Freie Presse.

The Jewish Encyclopedia reports, "In February 1881, a correspondent of the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums speaks of 'Anti-Semitism' as a designation which recently came into use ("Allg. Zeit. d. Jud." 1881, p. 138). On 19 July 1882, the editor says, 'This quite recent Anti-Semitism is hardly three years old.'"[26]

The word "antisemitism" was borrowed into English from German in 1881. Oxford English Dictionary editor James Murray wrote that it was not included in the first edition because "Anti-Semite and its family were then probably very new in English use, and not thought likely to be more than passing nonce-words... Would that anti-Semitism had had no more than a fleeting interest!"[27] The related term "philosemitism" was used by 1881.[28]

Usage

From the outset the term "anti-Semitism" bore special racial connotations and meant specifically prejudice against Jews.[2][7][14] The term is confusing, for in modern usage 'Semitic' designates a language group, not a race. In this sense, the term is a misnomer, since there are many speakers of Semitic languages (e.g. Arabs, Ethiopians, and Arameans) who are not the objects of antisemitic prejudices, while there are many Jews who do not speak Hebrew, a Semitic language. Though 'antisemitism' could be construed as prejudice against people who speak other Semitic languages, this is not how the term is commonly used.[29][30][31][32]

The term may be spelled with or without a hyphen (antisemitism or anti-Semitism). Many scholars and institutions favor the unhyphenated form.[33][34][35][36] Shmuel Almog argued, "If you use the hyphenated form, you consider the words 'Semitism', 'Semite', 'Semitic' as meaningful ... [I]n antisemitic parlance, 'Semites' really stands for Jews, just that."[37] Emil Fackenheim supported the unhyphenated spelling, in order to "[dispel] the notion that there is an entity 'Semitism' which 'anti-Semitism' opposes."[38] Others endorsing an unhyphenated term for the same reason include the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance,[33] historian Deborah Lipstadt,[7] Padraic O'Hare, professor of Religious and Theological Studies and Director of the Center for the Study of Jewish-Christian-Muslim Relations at Merrimack College; and historians Yehuda Bauer and James Carroll. According to Carroll, who first cites O'Hare and Bauer on "the existence of something called 'Semitism'", "the hyphenated word thus reflects the bipolarity that is at the heart of the problem of antisemitism".[39]

Objections to the usage of the term, such as the obsolete nature of the term Semitic as a racial term, have been raised since at least the 1930s.[25][40]

In 2020 ADL (the Anti-Defamation League) began to use the spelling "antisemitism."[41]

Definition

Though the general definition of antisemitism is hostility or prejudice against Jews, and, according to Olaf Blaschke, has become an "umbrella term for negative stereotypes about Jews",[42]:18 a number of authorities have developed more formal definitions.

Holocaust scholar and City University of New York professor Helen Fein defines it as "a persisting latent structure of hostile beliefs towards Jews as a collective manifested in individuals as attitudes, and in culture as myth, ideology, folklore and imagery, and in actions—social or legal discrimination, political mobilization against the Jews, and collective or state violence—which results in and/or is designed to distance, displace, or destroy Jews as Jews."

Elaborating on Fein's definition, Dietz Bering of the University of Cologne writes that, to antisemites, "Jews are not only partially but totally bad by nature, that is, their bad traits are incorrigible. Because of this bad nature: (1) Jews have to be seen not as individuals but as a collective. (2) Jews remain essentially alien in the surrounding societies. (3) Jews bring disaster on their 'host societies' or on the whole world, they are doing it secretly, therefore the anti-Semites feel obliged to unmask the conspiratorial, bad Jewish character."[43]

For Sonja Weinberg, as distinct from economic and religious anti-Judaism, antisemitism in its modern form shows conceptual innovation, a resort to 'science' to defend itself, new functional forms and organisational differences. It was anti-liberal, racialist and nationalist. It promoted the myth that Jews conspired to 'judaise' the world; it served to consolidate social identity; it channeled dissatisfactions among victims of the capitalist system; and it was used as a conservative cultural code to fight emancipation and liberalism.[42]:18–19

Bernard Lewis defines antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil." Thus, "it is perfectly possible to hate and even to persecute Jews without necessarily being anti-Semitic" unless this hatred or persecution displays one of the two features specific to antisemitism.[44]

There have been a number of efforts by international and governmental bodies to define antisemitism formally. The United States Department of State states that "while there is no universally accepted definition, there is a generally clear understanding of what the term encompasses." For the purposes of its 2005 Report on Global Anti-Semitism, the term was considered to mean "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity."[45]

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (now Fundamental Rights Agency), then an agency of the European Union, developed a more detailed working definition, which states: "Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities." It also adds that "such manifestations could also target the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity," but that "criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic." It provides contemporary examples of ways in which antisemitism may manifest itself, including: promoting the harming of Jews in the name of an ideology or religion; promoting negative stereotypes of Jews; holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of an individual Jewish person or group; denying the Holocaust or accusing Jews or Israel of exaggerating it; and accusing Jews of dual loyalty or a greater allegiance to Israel than their own country. It also lists ways in which attacking Israel could be antisemitic, and states that denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor, can be a manifestation of antisemitism—as can applying double standards by requiring of Israel a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation, or holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of the State of Israel.[46] Late in 2013, the definition was removed from the website of the Fundamental Rights Agency. A spokesperson said that it had never been regarded as official and that the agency did not intend to develop its own definition.[47] However, despite its disappearance from the website of the Fundamental Rights Agency, the definition has gained widespread international use. The definition has been adopted by the European Parliament Working Group on Antisemitism,[48] in 2010 it was adopted by the United States Department of State,[49] in 2014 it was adopted in the Operational Hate Crime Guidance of the UK College of Policing[50] and was also adopted by the Campaign Against Antisemitism,.[51]

In 2016, the definition was adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. The definition is accompanied by illustrative examples; for instance, "Accusing Jewish citizens of being more loyal to Israel, or to the alleged priorities of Jews worldwide, than to the interests of their own nations."[52][53]

Evolution of usage

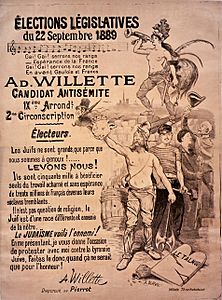

In 1879, Wilhelm Marr founded the Antisemiten-Liga (Anti-Semitic League).[54] Identification with antisemitism and as an antisemite was politically advantageous in Europe during the late 19th century. For example, Karl Lueger, the popular mayor of fin de siècle Vienna, skillfully exploited antisemitism as a way of channeling public discontent to his political advantage.[55] In its 1910 obituary of Lueger, The New York Times notes that Lueger was "Chairman of the Christian Social Union of the Parliament and of the Anti-Semitic Union of the Diet of Lower Austria.[56] In 1895 A. C. Cuza organized the Alliance Anti-semitique Universelle in Bucharest. In the period before World War II, when animosity towards Jews was far more commonplace, it was not uncommon for a person, an organization, or a political party to self-identify as an antisemite or antisemitic.

The early Zionist pioneer Leon Pinsker, a professional physician, preferred the clinical-sounding term Judeophobia to antisemitism, which he regarded as a misnomer. The word Judeophobia first appeared in his pamphlet "Auto-Emancipation", published anonymously in German in September 1882, where it was described as an irrational fear or hatred of Jews. According to Pinsker, this irrational fear was an inherited predisposition.[57]

Judeophobia is a form of demonopathy, with the distinction that the Jewish ghost has become known to the whole race of mankind, not merely to certain races.... Judeophobia is a psychic disorder. As a psychic disorder it is hereditary, and as a disease transmitted for two thousand years it is incurable.... Thus have Judaism and Jew-hatred passed through history for centuries as inseparable companions.... Having analyzed Judeophobia as an hereditary form of demonopathy, peculiar to the human race, and represented Jew-hatred as based upon an inherited aberration of the human mind, we must draw the important conclusion, that we must give up contending against these hostile impulses, just as we give up contending against every other inherited predisposition.[58]

In the aftermath of the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938, German propaganda minister Goebbels announced: "The German people is anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its rights restricted or to be provoked in the future by parasites of the Jewish race."[59]

After the 1945 victory of the Allies over Nazi Germany, and particularly after the full extent of the Nazi genocide against the Jews became known, the term "anti-Semitism" acquired pejorative connotations. This marked a full circle shift in usage, from an era just decades earlier when "Jew" was used as a pejorative term.[60][61] Yehuda Bauer wrote in 1984: "There are no anti-Semites in the world ... Nobody says, 'I am anti-Semitic.' You cannot, after Hitler. The word has gone out of fashion."[62]

Manifestations

Antisemitism manifests itself in a variety of ways. René König mentions social antisemitism, economic antisemitism, religious antisemitism, and political antisemitism as examples. König points out that these different forms demonstrate that the "origins of anti-Semitic prejudices are rooted in different historical periods." König asserts that differences in the chronology of different antisemitic prejudices and the irregular distribution of such prejudices over different segments of the population create "serious difficulties in the definition of the different kinds of anti-Semitism."[63] These difficulties may contribute to the existence of different taxonomies that have been developed to categorize the forms of antisemitism. The forms identified are substantially the same; it is primarily the number of forms and their definitions that differ. Bernard Lazare identifies three forms of antisemitism: Christian antisemitism, economic antisemitism, and ethnologic antisemitism.[64] William Brustein names four categories: religious, racial, economic and political.[65] The Roman Catholic historian Edward Flannery distinguished four varieties of antisemitism:[66]

- political and economic antisemitism, giving as examples Cicero[67] and Charles Lindbergh;[68]

- theological or religious antisemitism, sometimes known as anti-Judaism;[69]

- nationalistic antisemitism, citing Voltaire and other Enlightenment thinkers, who attacked Jews for supposedly having certain characteristics, such as greed and arrogance, and for observing customs such as kashrut and Shabbat;[70]

- and racial antisemitism, with its extreme form resulting in the Holocaust by the Nazis.[71]

Louis Harap separates "economic antisemitism" and merges "political" and "nationalistic" antisemitism into "ideological antisemitism". Harap also adds a category of "social antisemitism".[72]

- religious (Jew as Christ-killer),

- economic (Jew as banker, usurer, money-obsessed),

- social (Jew as social inferior, "pushy," vulgar, therefore excluded from personal contact),

- racist (Jews as an inferior "race"),

- ideological (Jews regarded as subversive or revolutionary),

- cultural (Jews regarded as undermining the moral and structural fiber of civilization).

Gustavo Perednik has argued that what he terms "Judeophobia" has a number of unique traits which set it apart from other forms of racism, including permanence, depth, obsessiveness, irrationality, endurance, ubiquity, and danger.[73] He also wrote in his book The Judeophobia that "The Jews were accused by the nationalists of being the creators of Communism; by the Communists of ruling Capitalism. If they live in non-Jewish countries, they are accused of double-loyalties; if they live in the Jewish country, of being racists. When they spend their money, they are reproached for being ostentatious; when they don't spend their money, of being avaricious. They are called rootless cosmopolitans or hardened chauvinists. If they assimilate, they are accused of being fifth-columnists, if they don't, of shutting themselves away."[74][75]

Harvard professor Ruth Wisse has argued that antisemitism is a political ideology that authoritarians use to consolidate power by unifying disparate groups which are opposed to liberalism.[76] One example she gives is the alleged antisemitism within the United Nations, which, in this view, functioned during the Cold War as a coalition-building technique between Soviet and Arab states, but now serves the same purpose among states opposed to the type of human-rights ideology for which the UN was created. She also cites as an example the formation of the Arab League.[76]

Seeking to update its resources for understanding how antisemitism manifests itself, in 2020 ADL (the Anti-Defamation League) published Antisemitism Uncovered: A Guide to Old Myths in a New Era.[77] The Guide is intended to be "a comprehensive resource with historical context, fact-based descriptions of prevalent antisemitic myths, contemporary examples and calls-to-action for addressing this hate."[78] It is organized around seven "myths" or antisemitic tropes, and composed of modules. This Guide also marked ADL's shift from using the spelling "anti-Semitism" to "antisemitism."[41][79]

Cultural antisemitism

Louis Harap defines cultural antisemitism as "that species of anti-Semitism that charges the Jews with corrupting a given culture and attempting to supplant or succeeding in supplanting the preferred culture with a uniform, crude, "Jewish" culture.[80] Similarly, Eric Kandel characterizes cultural antisemitism as being based on the idea of "Jewishness" as a "religious or cultural tradition that is acquired through learning, through distinctive traditions and education." According to Kandel, this form of antisemitism views Jews as possessing "unattractive psychological and social characteristics that are acquired through acculturation."[81] Niewyk and Nicosia characterize cultural antisemitism as focusing on and condemning "the Jews' aloofness from the societies in which they live."[82] An important feature of cultural antisemitism is that it considers the negative attributes of Judaism to be redeemable by education or by religious conversion.[83]

Religious antisemitism

Religious antisemitism, also known as anti-Judaism, is antipathy towards Jews because of their perceived religious beliefs. In theory, antisemitism and attacks against individual Jews would stop if Jews stopped practicing Judaism or changed their public faith, especially by conversion to the official or right religion. However, in some cases discrimination continues after conversion, as in the case of Christianized Marranos or Iberian Jews in the late 15th century and 16th century who were suspected of secretly practising Judaism or Jewish customs.[66]

Although the origins of antisemitism are rooted in the Judeo-Christian conflict, other forms of antisemitism have developed in modern times. Frederick Schweitzer asserts that, "most scholars ignore the Christian foundation on which the modern antisemitic edifice rests and invoke political antisemitism, cultural antisemitism, racism or racial antisemitism, economic antisemitism and the like."[84] William Nichols draws a distinction between religious antisemitism and modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds: "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion [...] a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." From the perspective of racial antisemitism, however, "the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism.[...] From the Enlightenment onward, it is no longer possible to draw clear lines of distinction between religious and racial forms of hostility towards Jews[...] Once Jews have been emancipated and secular thinking makes its appearance, without leaving behind the old Christian hostility towards Jews, the new term antisemitism becomes almost unavoidable, even before explicitly racist doctrines appear."

Some Christians such as the Catholic priest Ernest Jouin, who published the first French translation of the Protocols, combined religious and racial antisemitism, as in his statement that "From the triple viewpoint of race, of nationality, and of religion, the Jew has become the enemy of humanity."[85] The virulent antisemitism of Édouard Drumont, one of the most widely read Catholic writers in France during the Dreyfus Affair, likewise combined religious and racial antisemitism.[86][87][88]

Economic antisemitism

The underlying premise of economic antisemitism is that Jews perform harmful economic activities or that economic activities become harmful when they are performed by Jews.[89]

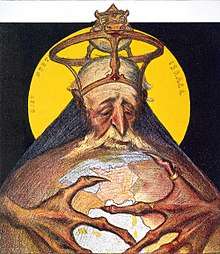

Linking Jews and money underpins the most damaging and lasting Antisemitic canards.[90] Antisemites claim that Jews control the world finances, a theory promoted in the fraudulent Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and later repeated by Henry Ford and his Dearborn Independent. In the modern era, such myths continue to be spread in books such as The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews published by the Nation of Islam, and on the internet. Derek Penslar writes that there are two components to the financial canards:[91]

- a) Jews are savages that "are temperamentally incapable of performing honest labor"

- b) Jews are "leaders of a financial cabal seeking world domination"

Abraham Foxman describes six facets of the financial canards:

- All Jews are wealthy[92]

- Jews are stingy and greedy[93]

- Powerful Jews control the business world[94]

- Jewish religion emphasizes profit and materialism[95]

- It is okay for Jews to cheat non-Jews[96]

- Jews use their power to benefit "their own kind"[97]

Gerald Krefetz summarizes the myth as "[Jews] control the banks, the money supply, the economy, and businesses—of the community, of the country, of the world".[98] Krefetz gives, as illustrations, many slurs and proverbs (in several different languages) which suggest that Jews are stingy, or greedy, or miserly, or aggressive bargainers.[99] During the nineteenth century, Jews were described as "scurrilous, stupid, and tight-fisted", but after the Jewish Emancipation and the rise of Jews to the middle- or upper-class in Europe were portrayed as "clever, devious, and manipulative financiers out to dominate [world finances]".[100]

Léon Poliakov asserts that economic antisemitism is not a distinct form of antisemitism, but merely a manifestation of theologic antisemitism (because, without the theological causes of the economic antisemitism, there would be no economic antisemitism). In opposition to this view, Derek Penslar contends that in the modern era, the economic antisemitism is "distinct and nearly constant" but theological antisemitism is "often subdued".[101]

An academic study by Francesco D'Acunto, Marcel Prokopczuk, and Michael Weber showed that people who live in areas of Germany that contain the most brutal history of antisemitic persecution are more likely to be distrustful of finance in general. Therefore, they tended to invest less money in the stock market and make poor financial decisions. The study concluded "that the persecution of minorities reduces not only the long-term wealth of the persecuted, but of the persecutors as well."[102]

Racial antisemitism

.jpg)

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews as a racial/ethnic group, rather than Judaism as a religion.[104]

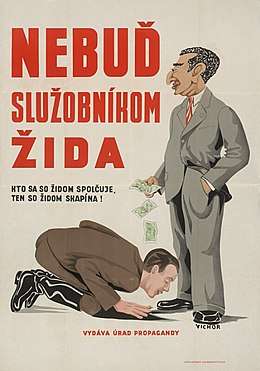

Racial antisemitism is the idea that the Jews are a distinct and inferior race compared to their host nations. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, it gained mainstream acceptance as part of the eugenics movement, which categorized non-Europeans as inferior. It more specifically claimed that Northern Europeans, or "Aryans", were superior. Racial antisemites saw the Jews as part of a Semitic race and emphasized their non-European origins and culture. They saw Jews as beyond redemption even if they converted to the majority religion.

Racial antisemitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the Jewish Emancipation, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering religious antisemitism, a combination of growing nationalism, the rise of eugenics, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the newer, and more virulent, racist antisemitism.

According to William Nichols, religious antisemitism may be distinguished from modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds. "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion... a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." However, with racial antisemitism, "Now the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism.... From the Enlightenment onward, it is no longer possible to draw clear lines of distinction between religious and racial forms of hostility towards Jews... Once Jews have been emancipated and secular thinking makes its appearance, without leaving behind the old Christian hostility towards Jews, the new term antisemitism becomes almost unavoidable, even before explicitly racist doctrines appear."[105]

In the early 19th century, a number of laws enabling emancipation of the Jews were enacted in Western European countries.[106][107] The old laws restricting them to ghettos, as well as the many laws that limited their property rights, rights of worship and occupation, were rescinded. Despite this, traditional discrimination and hostility to Jews on religious grounds persisted and was supplemented by racial antisemitism, encouraged by the work of racial theorists such as Joseph Arthur de Gobineau and particularly his Essay on the Inequality of the Human Race of 1853–5. Nationalist agendas based on ethnicity, known as ethnonationalism, usually excluded the Jews from the national community as an alien race.[108] Allied to this were theories of Social Darwinism, which stressed a putative conflict between higher and lower races of human beings. Such theories, usually posited by northern Europeans, advocated the superiority of white Aryans to Semitic Jews.[109]

Political antisemitism

| "The whole problem of the Jews exists only in nation states, for here their energy and higher intelligence, their accumulated capital of spirit and will, gathered from generation to generation through a long schooling in suffering, must become so preponderant as to arouse mass envy and hatred. In almost all contemporary nations, therefore – in direct proportion to the degree to which they act up nationalistially – the literary obscenity of leading the Jews to slaughter as scapegoats of every conceivable public and internal misfortune is spreading." |

| — Friedrich Nietzsche, 1886, [MA 1 475][110] |

William Brustein defines political antisemitism as hostility toward Jews based on the belief that Jews seek national and/or world power." Yisrael Gutman characterizes political antisemitism as tending to "lay responsibility on the Jews for defeats and political economic crises" while seeking to "exploit opposition and resistance to Jewish influence as elements in political party platforms."[111]

According to Viktor Karády, political antisemitism became widespread after the legal emancipation of the Jews and sought to reverse some of the consequences of that emancipation. [112]

Conspiracy theories

Holocaust denial and Jewish conspiracy theories are also considered forms of antisemitism.[113][114][115][116][117][117][118][119] Zoological conspiracy theories have been propagated by Arab media and Arabic language websites, alleging a "Zionist plot" behind the use of animals to attack civilians or to conduct espionage.[120]

New antisemitism

Starting in the 1990s, some scholars have advanced the concept of new antisemitism, coming simultaneously from the left, the right, and radical Islam, which tends to focus on opposition to the creation of a Jewish homeland in the State of Israel,[121] and they argue that the language of anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel are used to attack Jews more broadly. In this view, the proponents of the new concept believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism are often disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and they attribute this to antisemitism. Jewish scholar Gustavo Perednik posited in 2004 that anti-Zionism in itself represents a form of discrimination against Jews, in that it singles out Jewish national aspirations as an illegitimate and racist endeavor, and "proposes actions that would result in the death of millions of Jews".[122] It is asserted that the new antisemitism deploys traditional antisemitic motifs, including older motifs such as the blood libel.[121]

Critics of the concept view it as trivializing the meaning of antisemitism, and as exploiting antisemitism in order to silence debate and to deflect attention from legitimate criticism of the State of Israel, and, by associating anti-Zionism with antisemitism, misusing it to taint anyone opposed to Israeli actions and policies.[123]

Indology

German indologists arbitrarily identified "layers" in the Mahabharata and Bhagavad Gita with the objective of fueling European antisemitism via the Indo-Aryan migration theory.[124] This identification required equating Brahmins with Jews, resulting in anti-Brahmanism.[124]

History

Many authors see the roots of modern antisemitism in both pagan antiquity and early Christianity. Jerome Chanes identifies six stages in the historical development of antisemitism:[125]

- Pre-Christian anti-Judaism in ancient Greece and Rome which was primarily ethnic in nature

- Christian antisemitism in antiquity and the Middle Ages which was religious in nature and has extended into modern times

- Traditional Muslim antisemitism which was—at least, in its classical form—nuanced in that Jews were a protected class

- Political, social and economic antisemitism of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Europe which laid the groundwork for racial antisemitism

- Racial antisemitism that arose in the 19th century and culminated in Nazism in the 20th century

- Contemporary antisemitism which has been labeled by some as the New Antisemitism

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."[126]

Ancient world

The first clear examples of anti-Jewish sentiment can be traced to the 3rd century BCE to Alexandria,[66] the home to the largest Jewish diaspora community in the world at the time and where the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, was produced. Manetho, an Egyptian priest and historian of that era, wrote scathingly of the Jews. His themes are repeated in the works of Chaeremon, Lysimachus, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon, and in Apion and Tacitus.[127] Agatharchides of Cnidus ridiculed the practices of the Jews and the "absurdity of their Law", making a mocking reference to how Ptolemy Lagus was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BCE because its inhabitants were observing the Shabbat.[127] One of the earliest anti-Jewish edicts, promulgated by Antiochus IV Epiphanes in about 170–167 BCE, sparked a revolt of the Maccabees in Judea.[128]:238

In view of Manetho's anti-Jewish writings, antisemitism may have originated in Egypt and been spread by "the Greek retelling of Ancient Egyptian prejudices".[129] The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria describes an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in which thousands of Jews died.[130][131] The violence in Alexandria may have been caused by the Jews being portrayed as misanthropes.[132] Tcherikover argues that the reason for hatred of Jews in the Hellenistic period was their separateness in the Greek cities, the poleis.[133] Bohak has argued, however, that early animosity against the Jews cannot be regarded as being anti-Judaic or antisemitic unless it arose from attitudes that were held against the Jews alone, and that many Greeks showed animosity toward any group they regarded as barbarians.[134] Statements exhibiting prejudice against Jews and their religion can be found in the works of many pagan Greek and Roman writers.[135] Edward Flannery writes that it was the Jews' refusal to accept Greek religious and social standards that marked them out. Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the early third century BCE, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho, an Egyptian historian, wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers who had been taught by Moses "not to adore the gods." Edward Flannery describes antisemitism in ancient times as essentially "cultural, taking the shape of a national xenophobia played out in political settings."[66]

There are examples of Hellenistic rulers desecrating the Temple and banning Jewish religious practices, such as circumcision, Shabbat observance, study of Jewish religious books, etc. Examples may also be found in anti-Jewish riots in Alexandria in the 3rd century BCE.

The Jewish diaspora on the Nile island Elephantine, which was founded by mercenaries, experienced the destruction of its temple in 410 BCE.[136]

Relationships between the Jewish people and the occupying Roman Empire were at times antagonistic and resulted in several rebellions. According to Suetonius, the emperor Tiberius expelled from Rome Jews who had gone to live there. The 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon identified a more tolerant period in Roman-Jewish relations beginning in about 160 CE.[66] However, when Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire, the state's attitude towards the Jews gradually worsened.

James Carroll asserted: "Jews accounted for 10% of the total population of the Roman Empire. By that ratio, if other factors such as pogroms and conversions had not intervened, there would be 200 million Jews in the world today, instead of something like 13 million."[137]

Persecutions during the Middle Ages

In the late 6th century CE, the newly Catholicised Visigothic kingdom in Hispania issued a series of anti-Jewish edicts which forbad Jews from marrying Christians, practicing circumcision, and observing Jewish holy days.[138] Continuing throughout the 7th century, both Visigothic kings and the Church were active in creating social aggression and towards Jews with "civic and ecclesiastic punishments",[139] ranging between forced conversion, slavery, exile and death.[140]

From the 9th century, the medieval Islamic world classified Jews and Christians as dhimmis, and allowed Jews to practice their religion more freely than they could do in medieval Christian Europe. Under Islamic rule, there was a Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain that lasted until at least the 11th century.[141] It ended when several Muslim pogroms against Jews took place on the Iberian Peninsula, including those that occurred in Córdoba in 1011 and in Granada in 1066.[142][143][144] Several decrees ordering the destruction of synagogues were also enacted in Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Yemen from the 11th century. In addition, Jews were forced to convert to Islam or face death in some parts of Yemen, Morocco and Baghdad several times between the 12th and 18th centuries.[145] The Almohads, who had taken control of the Almoravids' Maghribi and Andalusian territories by 1147,[146] were far more fundamentalist in outlook compared to their predecessors, and they treated the dhimmis harshly. Faced with the choice of either death or conversion, many Jews and Christians emigrated.[147][148][149] Some, such as the family of Maimonides, fled east to more tolerant Muslim lands,[147] while some others went northward to settle in the growing Christian kingdoms.[150]

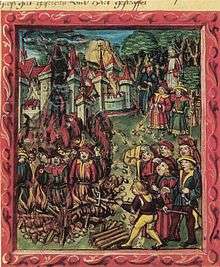

During the Middle Ages in Europe there was persecution against Jews in many places, with blood libels, expulsions, forced conversions and massacres. A main justification of prejudice against Jews in Europe was religious.

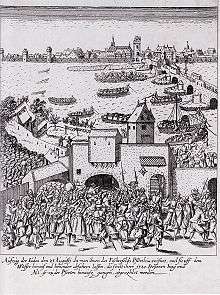

The persecution hit its first peak during the Crusades. In the First Crusade (1096) hundreds or even thousands of Jews were killed as the crusaders arrived.[151] This was the first major outbreak of anti-Jewish violence in Christian Europe outside Spain and was cited by Zionists in the 19th century as indicating the need for a state of Israel.[152]

In the Second Crusade (1147) the Jews in Germany were subject to several massacres. The Jews were also subjected to attacks by the Shepherds' Crusades of 1251 and 1320, as well as Rintfleisch knights in 1298. The Crusades were followed by expulsions, including, in 1290, the banishing of all English Jews; in 1394, the expulsion of 100,000 Jews in France;[153] and in 1421, the expulsion of thousands from Austria. Many of the expelled Jews fled to Poland.[154] In medieval and Renaissance Europe, a major contributor to the deepening of antisemitic sentiment and legal action among the Christian populations was the popular preaching of the zealous reform religious orders, the Franciscans (especially Bernardino of Feltre) and Dominicans (especially Vincent Ferrer), who combed Europe and promoted antisemitism through their often fiery, emotional appeals.[155]

As the Black Death epidemics devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, causing the death of a large part of the population, Jews were used as scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed in numerous persecutions. Although Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by issuing two papal bulls in 1348, the first on 6 July and an additional one several months later, 900 Jews were burned alive in Strasbourg, where the plague had not yet affected the city.[156]

17th century

During the mid-to-late 17th century the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was devastated by several conflicts, in which the Commonwealth lost over a third of its population (over 3 million people), and Jewish losses were counted in the hundreds of thousands. The first of these conflicts was the Khmelnytsky Uprising, when Bohdan Khmelnytsky's supporters massacred tens of thousands of Jews in the eastern and southern areas he controlled (today's Ukraine). The precise number of dead may never be known, but the decrease of the Jewish population during that period is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000, which also includes emigration, deaths from diseases and captivity in the Ottoman Empire, called jasyr.[157][158]

European immigrants to the United States brought antisemitism to the country as early as the 17th century. Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch governor of New Amsterdam, implemented plans to prevent Jews from settling in the city. During the Colonial Era, the American government limited the political and economic rights of Jews. It was not until the American Revolutionary War that Jews gained legal rights, including the right to vote. However, even at their peak, the restrictions on Jews in the United States were never as stringent as they had been in Europe.[159]

In the Zaydi imamate of Yemen, Jews were also singled out for discrimination in the 17th century, which culminated in the general expulsion of all Jews from places in Yemen to the arid coastal plain of Tihamah and which became known as the Mawza Exile.[160]

Enlightenment

In 1744, Frederick II of Prussia limited the number of Jews allowed to live in Breslau to only ten so-called "protected" Jewish families and encouraged a similar practice in other Prussian cities. In 1750 he issued the Revidiertes General Privilegium und Reglement vor die Judenschaft: the "protected" Jews had an alternative to "either abstain from marriage or leave Berlin" (quoting Simon Dubnow). In the same year, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa ordered Jews out of Bohemia but soon reversed her position, on the condition that Jews pay for their readmission every ten years. This extortion was known as malke-geld (queen's money). In 1752 she introduced the law limiting each Jewish family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II abolished most of these persecution practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish and Hebrew were eliminated from public records and that judicial autonomy was annulled. Moses Mendelssohn wrote that "Such a tolerance... is even more dangerous play in tolerance than open persecution."

Voltaire

According to Arnold Ages, Voltaire's "Lettres philosophiques, Dictionnaire philosophique, and Candide, to name but a few of his better known works, are saturated with comments on Jews and Judaism and the vast majority are negative".[161] Paul H. Meyer adds: "There is no question but that Voltaire, particularly in his latter years, nursed a violent hatred of the Jews and it is equally certain that his animosity...did have a considerable impact on public opinion in France."[162] Thirty of the 118 articles in Voltaire's Dictionnaire Philosophique concerned Jews and described them in consistently negative ways.[163]

Louis de Bonald and the Catholic Counter-Revolution

The counter-revolutionary Catholic royalist Louis de Bonald stands out among the earliest figures to explicitly call for the reversal of Jewish emancipation in the wake of the French Revolution.[164][165] Bonald's attacks on the Jews are likely to have influenced Napoleon's decision to limit the civil rights of Alsatian Jews.[166][167][168][169] Bonald's article Sur les juifs (1806) was one of the most venomous screeds of its era and furnished a paradigm which combined anti-liberalism, a defense of a rural society, traditional Christian antisemitism, and the identification of Jews with bankers and finance capital, which would in turn influence many subsequent right-wing reactionaries such as Roger Gougenot des Mousseaux, Charles Maurras, and Édouard Drumont, nationalists such as Maurice Barrès and Paolo Orano, and antisemitic socialists such as Alphonse Toussenel.[164][170][171] Bonald furthermore declared that the Jews were an "alien" people, a "state within a state", and should be forced to wear a distinctive mark to more easily identify and discriminate against them.[164][172]

Under the French Second Empire, the popular counter-revolutionary Catholic journalist Louis Veuillot propagated Bonald's arguments against the Jewish "financial aristocracy" along with vicious attacks against the Talmud and the Jews as a "deicidal people" driven by hatred to "enslave" Christians.[173][172] Between 1882 and 1886 alone, French priests published twenty antisemitic books blaming France's ills on the Jews and urging the government to consign them back to the ghettos, expel them, or hang them from the gallows.[172] Gougenot des Mousseaux's Le Juif, le judaïsme et la judaïsation des peuples chrétiens (1869) has been called a "Bible of modern antisemitism" and was translated into German by Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg.[172]

Imperial Russia

Thousands of Jews were slaughtered by Cossack Haidamaks in the 1768 massacre of Uman in the Kingdom of Poland. In 1772, the empress of Russia Catherine II forced the Jews into the Pale of Settlement – which was located primarily in present-day Poland, Ukraine and Belarus – and to stay in their shtetls and forbade them from returning to the towns that they occupied before the partition of Poland.[174] From 1804, Jews were banned from their villages, and began to stream into the towns.[175] A decree by emperor Nicholas I of Russia in 1827 conscripted Jews under 18 years of age into the cantonist schools for a 25-year military service in order to promote baptism.[176] Policy towards Jews was liberalised somewhat under Czar Alexander II (r. 1855–1881).[177] However, his assassination in 1881 served as a pretext for further repression such as the May Laws of 1882. Konstantin Pobedonostsev, nicknamed the "black czar" and tutor to the czarevitch, later crowned Czar Nicholas II, declared that "One third of the Jews must die, one third must emigrate, and one third be converted to Christianity".[178]

Islamic antisemitism in the 19th century

Historian Martin Gilbert writes that it was in the 19th century that the position of Jews worsened in Muslim countries. Benny Morris writes that one symbol of Jewish degradation was the phenomenon of stone-throwing at Jews by Muslim children. Morris quotes a 19th-century traveler: "I have seen a little fellow of six years old, with a troop of fat toddlers of only three and four, teaching [them] to throw stones at a Jew, and one little urchin would, with the greatest coolness, waddle up to the man and literally spit upon his Jewish gaberdine. To all this the Jew is obliged to submit; it would be more than his life was worth to offer to strike a Mahommedan."[179]

In the middle of the 19th century, J. J. Benjamin wrote about the life of Persian Jews, describing conditions and beliefs that went back to the 16th century: "…they are obliged to live in a separate part of town… Under the pretext of their being unclean, they are treated with the greatest severity and should they enter a street, inhabited by Mussulmans, they are pelted by the boys and mobs with stones and dirt…."[180]

In Jerusalem at least, conditions for some Jews improved. Moses Montefiore, on his seventh visit in 1875, noted that fine new buildings had sprung up and; 'surely we're approaching the time to witness God's hallowed promise unto Zion.' Muslim and Christian Arabs participated in Purim and Passover; Arabs called the Sephardis 'Jews, sons of Arabs'; the Ulema and the Rabbis offered joint prayers for rain in time of drought.[181]

At the time of the Dreyfus trial in France, 'Muslim comments usually favoured the persecuted Jew against his Christian persecutors'.[182]

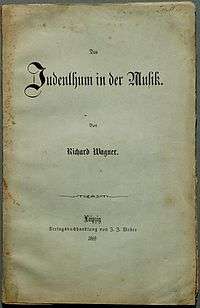

Secular or racial antisemitism

In 1850 the German composer Richard Wagner – who has been called "the inventor of modern antisemitism"[183] – published Das Judenthum in der Musik (roughly "Jewishness in Music"[183]) under a pseudonym in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. The essay began as an attack on Jewish composers, particularly Wagner's contemporaries, and rivals, Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer, but expanded to accuse Jews of being a harmful and alien element in German culture, who corrupted morals and were, in fact, parasites incapable of creating truly "German" art. The crux was the manipulation and control by the Jews of the money economy:[183]

According to the present constitution of this world, the Jew in truth is already more than emancipated: he rules, and will rule, so long as Money remains the power before which all our doings and our dealings lose their force.[183]

Although originally published anonymously, when the essay was republished 19 years later, in 1869, the concept of the corrupting Jew had become so widely held that Wagner's name was affixed to it.[183]

Antisemitism can also be found in many of the Grimms' Fairy Tales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, published from 1812 to 1857. It is mainly characterized by Jews being the villain of a story, such as in "The Good Bargain" ("Der gute Handel") and "The Jew Among Thorns" ("Der Jude im Dorn").

The middle 19th century saw continued official harassment of the Jews, especially in Eastern Europe under Czarist influence. For example, in 1846, 80 Jews approached the governor in Warsaw to retain the right to wear their traditional dress, but were immediately rebuffed by having their hair and beards forcefully cut, at their own expense.[184]

In America, even such influential figures as Walt Whitman tolerated bigotry toward the Jews. During his time as editor of the Brooklyn Eagle (1846–1848), the newspaper published historical sketches casting Jews in a bad light.[185]

The Dreyfus Affair was an infamous antisemitic event of the late 19th century and early 20th century. Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery captain in the French Army, was accused in 1894 of passing secrets to the Germans. As a result of these charges, Dreyfus was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island. The actual spy, Marie Charles Esterhazy, was acquitted. The event caused great uproar among the French, with the public choosing sides on the issue of whether Dreyfus was actually guilty or not. Émile Zola accused the army of corrupting the French justice system. However, general consensus held that Dreyfus was guilty: 80% of the press in France condemned him. This attitude among the majority of the French population reveals the underlying antisemitism of the time period.[186]

Adolf Stoecker (1835–1909), the Lutheran court chaplain to Kaiser Wilhelm I, founded in 1878 an antisemitic, anti-liberal political party called the Christian Social Party.[187][188] This party always remained small, and its support dwindled after Stoecker's death, with most of its members eventually joining larger conservative groups such as the German National People's Party.

Some scholars view Karl Marx's essay On The Jewish Question as antisemitic, and argue that he often used antisemitic epithets in his published and private writings.[189][190][191] These scholars argue that Marx equated Judaism with capitalism in his essay, helping to spread that idea. Some further argue that the essay influenced National Socialist, as well as Soviet and Arab antisemites.[192][193][194] Marx himself had Jewish ancestry, and Albert Lindemann and Hyam Maccoby have suggested that he was embarrassed by it.[195][196] Others argue that Marx consistently supported Prussian Jewish communities' struggles to achieve equal political rights. These scholars argue that "On the Jewish Question" is a critique of Bruno Bauer's arguments that Jews must convert to Christianity before being emancipated, and is more generally a critique of liberal rights discourses and capitalism.[197][198][199][200] Iain Hamphsher-Monk wrote that "This work [On The Jewish Question] has been cited as evidence for Marx's supposed anti-semitism, but only the most superficial reading of it could sustain such an interpretation."[201] David McLellan and Francis Wheen argue that readers should interpret On the Jewish Question in the deeper context of Marx's debates with Bruno Bauer, author of The Jewish Question, about Jewish emancipation in Germany. Wheen says that "Those critics, who see this as a foretaste of 'Mein Kampf', overlook one, essential point: in spite of the clumsy phraseology and crude stereotyping, the essay was actually written as a defense of the Jews. It was a retort to Bruno Bauer, who had argued that Jews should not be granted full civic rights and freedoms unless they were baptised as Christians".[202] According to McLellan, Marx used the word Judentum colloquially, as meaning commerce, arguing that Germans must be emancipated from the capitalist mode of production not Judaism or Jews in particular. McLellan concludes that readers should interpret the essay's second half as "an extended pun at Bauer's expense".[203]

20th century

Between 1900 and 1924, approximately 1.75 million Jews migrated to America, the bulk from Eastern Europe escaping the pogroms. Before 1900 American Jews had always amounted to less than 1% of America's total population, but by 1930 Jews formed about 3.5%. This increase, combined with the upward social mobility of some Jews, contributed to a resurgence of antisemitism. In the first half of the 20th century, in the US, Jews were discriminated against in employment, access to residential and resort areas, membership in clubs and organizations, and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrolment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. The lynching of Leo Frank by a mob of prominent citizens in Marietta, Georgia in 1915 turned the spotlight on antisemitism in the United States.[204] The case was also used to build support for the renewal of the Ku Klux Klan which had been inactive since 1870.[205]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Beilis Trial in Russia represented modern incidents of blood-libels in Europe. During the Russian Civil War, close to 50,000 Jews were killed in pogroms.[206]

Antisemitism in America reached its peak during the interwar period. The pioneer automobile manufacturer Henry Ford propagated antisemitic ideas in his newspaper The Dearborn Independent (published by Ford from 1919 to 1927). The radio speeches of Father Coughlin in the late 1930s attacked Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and promoted the notion of a Jewish financial conspiracy. Some prominent politicians shared such views: Louis T. McFadden, Chairman of the United States House Committee on Banking and Currency, blamed Jews for Roosevelt's decision to abandon the gold standard, and claimed that "in the United States today, the Gentiles have the slips of paper while the Jews have the lawful money".[207]

In the early 1940s the aviator Charles Lindbergh and many prominent Americans led The America First Committee in opposing any involvement in the war against Fascism. During his July 1936 visit to Nazi Germany, a few weeks before the 1936 Summer Olympics, Lindbergh wrote letters saying that there was "more intelligent leadership in Germany than is generally recognized". The German American Bund held parades in New York City during the late 1930s, where members wore Nazi uniforms and raised flags featuring swastikas alongside American flags.

Sometimes race riots, as in Detroit in 1943, targeted Jewish businesses for looting and burning.[208]

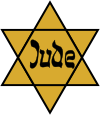

In Germany, Nazism led Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, who came to power on 30 January 1933 shortly afterwards instituted repressive legislation which denied the Jews basic civil rights.[209][210] In September 1935, the Nuremberg Laws prohibited sexual relations and marriages between "Aryans" and Jews as Rassenschande ("race disgrace") and stripped all German Jews, even quarter- and half-Jews, of their citizenship, (their official title became "subjects of the state").[211] It instituted a pogrom on the night of 9–10 November 1938, dubbed Kristallnacht, in which Jews were killed, their property destroyed and their synagogues torched.[212] Antisemitic laws, agitation and propaganda were extended to German-occupied Europe in the wake of conquest, often building on local antisemitic traditions.

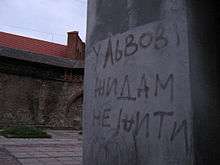

In the east the Third Reich forced Jews into ghettos in Warsaw, in Kraków, in Lvov, in Lublin and in Radom.[213] After the beginning of the war between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1941 a campaign of mass murder, conducted by the Einsatzgruppen, culminated from 1942 to 1945 in systematic genocide: the Holocaust.[214] Eleven million Jews were targeted for extermination by the Nazis, and some six million were eventually killed.[214][215][216]

Antisemitism was commonly used as an instrument for settling personal conflicts in the Soviet Union, starting with the conflict between Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky and continuing through numerous conspiracy-theories spread by official propaganda. Antisemitism in the USSR reached new heights after 1948 during the campaign against the "rootless cosmopolitan" (euphemism for "Jew") in which numerous Yiddish-language poets, writers, painters and sculptors were killed or arrested.[217][218] This culminated in the so-called Doctors' Plot (1952–1953). Similar antisemitic propaganda in Poland resulted in the flight of Polish Jewish survivors from the country.[218]

After the war, the Kielce pogrom and the "March 1968 events" in communist Poland represented further incidents of antisemitism in Europe. The anti-Jewish violence in postwar Poland has a common theme of blood libel rumours.[219][220]

21st-century European antisemitism

Physical assaults against Jews in those countries included beatings, stabbings and other violence, which increased markedly, sometimes resulting in serious injury and death.[221][222] A 2015 report by the US State Department on religious freedom declared that "European anti-Israel sentiment crossed the line into anti-Semitism."[223]

This rise in antisemitic attacks is associated with both the Muslim anti-Semitism and the rise of far-right political parties as a result of the economic crisis of 2008.[224] This rise in the support for far right ideas in western and eastern Europe has resulted in the increase of antisemitic acts, mostly attacks on Jewish memorials, synagogues and cemeteries but also a number of physical attacks against Jews.[225]

In Eastern Europe the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the instability of the new states has brought the rise of nationalist movements and the accusation against Jews for the economic crisis, taking over the local economy and bribing the government, along with traditional and religious motives for antisemitism such as blood libels. Most of the antisemitic incidents are against Jewish cemeteries and building (community centers and synagogues). Nevertheless, there were several violent attacks against Jews in Moscow in 2006 when a neo-Nazi stabbed 9 people at the Bolshaya Bronnaya Synagogue,[226] the failed bomb attack on the same synagogue in 1999,[227] the threats against Jewish pilgrims in Uman, Ukraine[228] and the attack against a menorah by extremist Christian organization in Moldova in 2009.[229]

According to Paul Johnson, antisemitic policies are a sign of a state which is poorly governed.[230] While no European state currently has such policies, the Economist Intelligence Unit notes the rise in political uncertainty, notably populism and nationalism, as something that is particularly alarming for Jews.[231]

21st-century Arab antisemitism

Robert Bernstein, founder of Human Rights Watch, says that antisemitism is "deeply ingrained and institutionalized" in "Arab nations in modern times."[232]

In a 2011 survey by the Pew Research Center, all of the Muslim-majority Middle Eastern countries polled held few positive opinions of Jews. In the questionnaire, only 2% of Egyptians, 3% of Lebanese Muslims, and 2% of Jordanians reported having a positive view of Jews. Muslim-majority countries outside the Middle East similarly had few who held positive views of Jews, with 4% of Turks and 9% of Indonesians viewing Jews favorably.[233]

According to a 2011 exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, United States, some of the dialogue from Middle East media and commentators about Jews bear a striking resemblance to Nazi propaganda.[234] According to Josef Joffe of Newsweek, "anti-Semitism—the real stuff, not just bad-mouthing particular Israeli policies—is as much part of Arab life today as the hijab or the hookah. Whereas this darkest of creeds is no longer tolerated in polite society in the West, in the Arab world, Jew hatred remains culturally endemic."[235]

Muslim clerics in the Middle East have frequently referred to Jews as descendants of apes and pigs, which are conventional epithets for Jews and Christians.[236][237][238]

According to professor Robert Wistrich, director of the Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism (SICSA), the calls for the destruction of Israel by Iran or by Hamas, Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad, or the Muslim Brotherhood, represent a contemporary mode of genocidal antisemitism.[239]

Causes

Antisemitism has been explained in terms of racism, xenophobia, projected guilt, displaced aggression, and the search for a scapegoat.[240] Some explanations assign partial blame to the perception of Jewish people as unsociable. Such a perception may have arisen by many Jews having strictly kept to their own communities, with their own practices and laws.[241]

It has also been suggested that parts of antisemitism arose from a perception of Jewish people as greedy (as often used in stereotypes of Jews), and this perception has probably evolved in Europe during Medieval times where a large portion of money lending was operated by Jews.[242] Factors contributing to this situation included that Jews were restricted from other professions,[242] while the Christian Church declared for their followers that money lending constituted immoral "usury".[243]

Prevention through education

Education plays an important role in addressing and overcoming prejudice and countering social discrimination.[244] However, education is not only about challenging the conditions of intolerance and ignorance in which anti-Semitism manifests itself; it is also about building a sense of global citizenship and solidarity, respect for, and enjoyment of diversity and the ability to live peacefully together as active, democratic citizens. Education equips learners with the knowledge to identify anti-Semitism and biased or prejudiced messages, and raises awareness about the forms, manifestations and impact of anti-Semitism faced by Jews and Jewish communities.[244]

Current situation

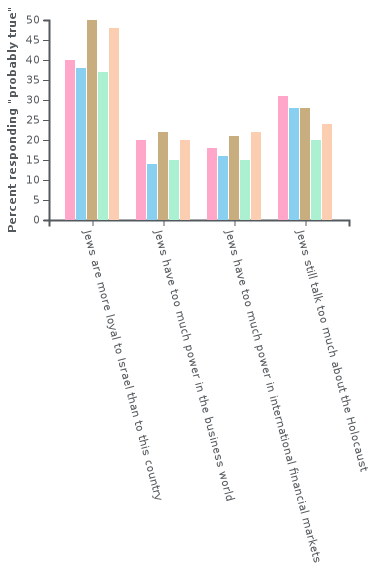

A March 2008 report by the U.S. State Department found that there was an increase in antisemitism across the world, and that both old and new expressions of antisemitism persist.[245] A 2012 report by the U.S. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor also noted a continued global increase in antisemitism, and found that Holocaust denial and opposition to Israeli policy at times was used to promote or justify blatant antisemitism.[246] In 2014, the ADL conducted a study titled "Global 100: An Index of Anti-Semitism", which also reported high antisemitism figures around the world and, among other findings, that as many as "27% of people who have never met a Jew nevertheless harbor strong prejudices against him".[247] Their study also showed that 75% of Muslims in the Middle East and North Africa held antisemitic views.[247]

Africa

Middle Africa

Cameroon

In 2019, deputy justice minister Jean de Dieu Momo advanced an antisemitic canard during prime time on Cameroon Radio Television, and suggested that Jewish people had brought the holocaust upon themselves.[248][249]

Northern Africa

Algeria

Almost all Jews in Algeria left upon independence in 1962. Algeria's 140,000 Jews had French citizenship since 1870 (briefly revoked by Vichy France in 1940), and they mainly went to France, with some going to Israel.

Egypt

In Egypt, Dar al-Fadhilah published a translation of Henry Ford's antisemitic treatise, The International Jew, complete with distinctly antisemitic imagery on the cover.[250]

On 5 May 2001, after Shimon Peres visited Egypt, the Egyptian al-Akhbar internet paper said that "lies and deceit are not foreign to Jews[...]. For this reason, Allah changed their shape and made them into monkeys and pigs."[251]

In July 2012, Egypt's Al Nahar channel fooled actors into thinking they were on an Israeli television show and filmed their reactions to being told it was an Israeli television show. In response, some of the actors launched into antisemitic rants or dialogue, and many became violent. Actress Mayer El Beblawi said that "Allah did not curse the worm and moth as much as he cursed the Jews" while actor Mahmoud Abdel Ghaffar launched into a violent rage and said, "You brought me someone who looks like a Jew... I hate the Jews to death" after finding out it was a prank.[252][253]

Libya

Libya had once one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, dating back to 300 BCE. Despite the repression of Jews in the late 1930s, as a result of the pro-Nazi Fascist Italian regime, Jews were a third of the population of Libya till 1941. In 1942 the Nazi German troops occupied the Jewish quarter of Benghazi, plundering shops and deporting more than 2,000 Jews across the desert. Sent to work in labor camps, more than one-fifth of this group of Jews perished. A series of pogroms started in November 1945, while more than 140 Jews were killed in Tripoli and most synagogues in the city looted.[254] Upon Libya's independence in 1951, most of the Jewish community emigrated from Libya. After the Suez Crisis in 1956, another series of pogroms forced all but about 100 Jews to flee. When Muammar al-Gaddafi came to power in 1969, all remaining Jewish property was confiscated and all debts to Jews canceled.

Morocco

Jewish communities, in Islamic times often living in ghettos known as mellah, have existed in Morocco for at least 2,000 years. Intermittent large scale massacres (such as that of 6,000 Jews in Fez in 1033, over 100,000 Jews in Fez and Marrakesh in 1146 and again in Marrakesh in 1232)[179][255] were accompanied by systematic discrimination through the years. In 1875, 20 Jews were killed by a mob in Demnat, Morocco; elsewhere in Morocco, Jews were attacked and killed in the streets in broad daylight.[256] While the pro-Nazi Vichy regime during World War II passed discriminatory laws against Jews, King Muhammad prevented deportation of Jews to death camps (although Jews with French, as opposed to Moroccan, citizenship, being directly subject to Vichy law, were still deported.) In 1948, approximately 265,000 Jews lived in Morocco. Between 5,000 and 8,000 live there now. In June 1948, soon after Israel was established and in the midst of the first Arab-Israeli war, riots against Jews broke out in Oujda and Djerada, killing 44 Jews. In 1948–9, 18,000 Jews left the country for Israel. After this, Jewish emigration continued (to Israel and elsewhere), but slowed to a few thousand per year. Through the early fifties, Zionist organizations encouraged emigration, particularly in the poorer south of the country, seeing Moroccan Jews as valuable contributors to the Jewish State: In 1955, Morocco attained independence and emigration to Israel has increased further until 1956 then it was prohibited until 1963, then resumed.[257] By 1967, only 60,000 Jews remained in Morocco. The Six-Day War in 1967 led to increased Arab-Jewish tensions worldwide, including Morocco. By 1971, the Jewish population was down to 35,000; however, most of this wave of emigration went to Europe and North America rather than Israel.

Tunisia

Jews have lived in Tunisia for at least 2,300 years. In the 13th century, Jews were expelled from their homes in Kairouan and were ultimately restricted to ghettos, known as hara. Forced to wear distinctive clothing, several Jews earned high positions in the Tunisian government. Several prominent international traders were Tunisian Jews. From 1855 to 1864, Muhammad Bey relaxed dhimmi laws, but reinstated them in the face of anti-Jewish riots that continued at least until 1869. Tunisia, as the only Middle Eastern country under direct Nazi control during World War II, was also the site of racist antisemitic measures activities such as the yellow star, prison camps, deportations, and other persecution. In 1948, approximately 105,000 Jews lived in Tunisia. Only about 1,500 remain there today. Following Tunisia's independence from France in 1956, a number of anti-Jewish policies led to emigration, of which half went to Israel and the other half to France. After attacks in 1967, Jewish emigration both to Israel and France accelerated. There were also attacks in 1982, 1985, and most recently in 2002 when a suicide bombing[258] in Djerba took 21 lives (most of them German tourists) near the local synagogue, in a terrorist attack claimed by Al-Qaeda.

In modern-day Tunisia, there have been many instances of antisemitic acts and statements. Since the government is not quick to condemn them, antisemitism spreads throughout Tunisian society.[259] Following the Ben Ali regime, there have been an increasing number of public offenses against Jews in Tunisia. For example, in February 2012, when Egyptian cleric Wagdi Ghanaim entered Tunisia, he was welcomed by Islamists who chanted "Death to the Jews" as a sign of their support. The following month, during protests in Tunis, a Salafi sheik told young Tunisians to gather and learn to kill Jews.[259]

In the past, The Tunisian government has made efforts to block Jews from entering high positions, and some moderate members have tried to cover up the more extremist antisemitic efforts by appointing Jews to governmental positions, however, it is known that Muslim clerics believe that if the Muslim Brotherhood leads the regime, that will enhance their hatred towards Jews.[259] In response to the prevalent antisemitism, the Tunisian government has publicly protected the dwindling population and its marks of Jewish culture, for example, synagogues, and advised them to settle in Djerba, a French tourist attraction.[260]

Southern Africa

South Africa

Antisemitism has been present in the history of South Africa since Europeans first set foot ashore on the Cape Peninsula. In the years 1652–1795 Jews were not allowed to settle at the Cape. An 1868 Act would sanction religious discrimination.[261] Antisemitism reached its apotheosis in the years leading up to World War II. Inspired by the rise of national socialism in Germany the Ossewabrandwag (OB) – whose membership accounted for almost 25% of the 1940 Afrikaner population – and the National Party faction New Order would champion a more programmatic solution to the 'Jewish problem'.[262]

Asia

Eastern Asia

Japan

The Japanese first learned about antisemitism in 1918, during the cooperation of the Imperial Japanese Army with the White movement in Siberia. White Army soldiers had been issued copies of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and "The Protocols continue to be used as evidence of Jewish conspiracies even though they are widely acknowledged to be a forgery.[263] During World War II, Nazi Germany encouraged Japan to adopt antisemitic policies. In the post-war period, extremist groups and ideologues have promoted conspiracy theories.

Southern Asia

Pakistan

The U.S. State Department's first Report on Global Anti-Semitism mentioned a strong feeling of antisemitism in Pakistan.[264] In Pakistan, a country without Jewish communities, antisemitic sentiment fanned by antisemitic articles in the press is widespread.[265]

In Pakistan, Jews are often regarded as miserly.[266] After Israel's independence in 1948, violent incidents occurred against Pakistan's small Jewish community of about 2,000 Bene Israel Jews. The Magain Shalome Synagogue in Karachi was attacked, as were individual Jews. The persecution of Jews resulted in their exodus via India to Israel (see Pakistanis in Israel), the UK, Canada and other countries. The Peshawar Jewish community ceased to exist[267] although a small community reportedly still exists in Karachi.

A substantial number of people in Pakistan believe that the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York were a secret Jewish conspiracy organized by Israel's MOSSAD, as were the 7 July 2005 London bombings, allegedly perpetrated by Jews in order to discredit Muslims. Pakistani political commentator Zaid Hamid claimed that Indian Jews perpetrated the 2008 Mumbai attacks.[268] Such allegations echo traditional antisemitic theories.[269][270] The Jewish religious movement of Chabad Lubavich had a mission house in Mumbai, India that was attacked in the 2008 Mumbai attacks, perpetrated by militants connected to Pakistan led by Ajmal Kasab, a Pakistani national.[271][272] Antisemitic intents were evident from the testimonies of Kasab following his arrest and trial.[273]

Southeastern Asia

Malaysia

Although Malaysia presently has no substantial Jewish population, the country has reportedly become an example of a phenomenon called "antisemitism without Jews."[274][275]

In his treatise on Malay identity, "The Malay Dilemma," which was published in 1970, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad wrote: "The Jews are not only hooked-nosed... but understand money instinctively.... Jewish stinginess and financial wizardry gained them the economic control of Europe and provoked antisemitism which waxed and waned throughout Europe through the ages."[276]

The Malay-language Utusan Malaysia daily stated in an editorial that Malaysians "cannot allow anyone, especially the Jews, to interfere secretly in this country's business... When the drums are pounded hard in the name of human rights, the pro-Jewish people will have their best opportunity to interfere in any Islamic country," the newspaper said. "We might not realize that the enthusiasm to support actions such as demonstrations will cause us to help foreign groups succeed in their mission of controlling this country." Prime Minister Najib Razak's office subsequently issued a statement late Monday saying Utusan's claim did "not reflect the views of the government."[277][278][279]

Indonesia

Indonesian Jews face anti-Jewish discrimination.[280]

Western Asia

Iran

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, former president of Iran, has frequently been accused of denying the Holocaust.

Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of Iran, has repeatedly doubted the validity of the reported casualties of the Holocaust. In one meeting he claimed that the Zionists have had "close relations" with the Nazi leaders and that "providing exaggerated statistics [of the Holocaust] has been a method to justify the Zionists' cruel treatment of the Palestinians".[281]

In July 2012, the winner of Iran's first annual International Wall Street Downfall Cartoon Festival, jointly sponsored by the semi-state-run Iranian media outlet Fars News, was an antisemitic cartoon depicting Jews praying before the New York Stock Exchange, which is made to look like the Western Wall. Other cartoons in the contest were antisemitic as well. The national director of the Anti-Defamation League, Abraham Foxman, condemned the cartoon, stating that "Here's the anti-Semitic notion of Jews and their love for money, the canard that Jews 'control' Wall Street, and a cynical perversion of the Western Wall, the holiest site in Judaism," and "Once again Iran takes the prize for promoting antisemitism."[282][283][284]

ADL/Global 100 reported in 2014 that 56% of Iranians hold antisemitic beliefs, and 18% of them agreed that Jews probably talk too much about the Holocaust.[285] However, the reported results (56%) were reported to be the lowest in the Middle East.[286]

Iranian Jews along with Christians and Zoroastrians are protected under the Constitution and have seats reserved for them in the Iranian Parliament, However, de facto harassment still occurs.[287][288]

Lebanon

In 2004, Al-Manar, a media network affiliated with Hezbollah, aired a drama series, The Diaspora, which observers allege is based on historical antisemitic allegations. BBC correspondents who have watched the program says it quotes extensively from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.[289]

Palestine

In March 2011, the Israeli government issued a paper claiming that "Anti-Israel and anti-Semitic messages are heard regularly in the government and private media and in the mosques and are taught in school books," to the extent that they are "an integral part of the fabric of life inside the PA."[292] In August 2012, Israeli Strategic Affairs Ministry director-general Yossi Kuperwasser stated that Palestinian incitement to antisemitism is "going on all the time" and that it is "worrying and disturbing." At an institutional level, he said the PA has been promoting three key messages to the Palestinian people that constitute incitement: "that the Palestinians would eventually be the sole sovereign on all the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea; that Jews, especially those who live in Israel, were not really human beings but rather 'the scum of mankind'; and that all tools were legitimate in the struggle against Israel and the Jews."[293] In August 2014, the Hamas' spokesman in Doha said on live television that Jews use blood to make matzos.[294]

Saudi Arabia