History of the Jews in India

The history of the Jews in India reaches back to ancient times.[1][2][3][4] Judaism was one of the first foreign religions to arrive in India in recorded history.[5] Indian Jews are a religious minority of India, but, unlike many parts of the world, have historically lived in India without any instances of anti-Semitism from the local majority populace.[6] The better-established ancient communities have assimilated many local traditions through cultural diffusion.[7] While some Jews state their ancestors arrived in India during the time of the Kingdom of Judah, others identify themselves as descendants of Israel's Ten Lost Tribes.[8] It is estimated that India's Jewish population peaked at around 20,000 in the mid-1940s, and began to rapidly decline due to their emigration to Israel after its creation in 1948.[9]

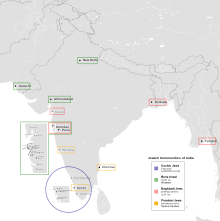

Jewish groups in India

In addition to Jewish expatriates[10] and recent immigrants, there are seven Jewish groups in India:

- The Malabar component of the Cochin Jews, according to Shalva Weil, claim to have arrived in India together with the Hebrew King Solomon's merchants. The Cochin Jews settled in Kerala as traders.[2] The fair-complexioned component is of European-Jewish descent, both Ashkenazi and Sephardi.[11][12]

- Chennai Jews: The so-called Spanish and Portuguese Jews, Paradesi Jews and British Jews arrived at Madras during the 16th century. They were diamond businesspeople[13] and of Sephardi and Ashkenazi heritage. Following expulsion from Iberia in 1492 by the Alhambra Decree, a few families of Sephardic Jews eventually made their way to Madras in the 16th century. They maintained trade connections to Europe, and their language skills were useful. Although the Sephardim mostly spoke Ladino (i.e. Spanish or Judeo-Spanish), in India they learned Tamil and Judeo-Malayalam from the Malabar Jews.[14]

- Nagercoil Jews: The so-called Syrian Jews, Musta'arabi Jews were Arab Jews who arrived at Nagercoil and Kanyakumari District in 52 AD along with the arrival of St. Thomas. Most of them were merchants and had also settled around the town of Thiruvithamcode.[15] By the turn of the 20th century, most of the families made their way to Cochin and eventually migrated to Israel. In their early days, they maintained trade connections to Europe through the nearby ports of Colachal and Thengaipattinam, and their language skills were useful to the Travancore Kings.[16] As historians Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George cited the reason the Jews selecting Nagercoil as their settlement was for the towns salubrious climate and its significant Christian population.[17]

- The Jews of Goa: These were Portuguese Jews who fled to Portuguese Goa after the commencement of the Inquisition in Portugal. The community consisted mainly of "New Christians" who were Jews by blood and had converted under the duress of the Inquisition. This group was the target of heavy persecution with the start of the Goan Inquisition, which put on trial famed physician Garcia de Orta, among others.

- Another branch of the Bene Israel community resided in Karachi until the Partition of India in 1947, when they fled to India (in particular, to Mumbai).[18] Many of them also moved to Israel. The Jews from the Sindh, Punjab and Pathan areas are often incorrectly called Bani Israel Jews. The Jewish community who used to reside in other parts of what became Pakistan (such as Lahore or Peshawar) also fled to India in 1947, in a similar manner to the larger Karachi Jewish community.

- The Baghdadi Jews arrived in the city of Surat from Iraq (and other Arab states), Iran and Afghanistan about 250 years ago.[3]

- The Bnei Menashe meaning "Sons of Manassah" in Hebrew, are Mizo and Kuki tribesmen in Manipur and Mizoram who are recent converts to the modern form of Judaism, but claim ancestry reaching back to one of the lost ten tribes of Israel; specifically, one of the sons of Joseph.[19]

- Similarly, the small Telugu speaking group, the Bene Ephraim (meaning "Sons of Ephraim" in Hebrew) also claim ancestry from Ephraim, one of the sons of Joseph and a lost tribe of ancient Israel. Also called "Telugu Jews", their observance of modern Judaism dates to 1981.

Cochin Jews

The oldest of the Indian Jewish communities was in the erstwhile Cochin Kingdom.[2][20] The traditional account is that traders of Judea arrived at Cranganore, an ancient port near Cochin in 562 BC, and that more Jews came as exiles from Israel in the year 70 AD, after the destruction of the Second Temple.[21] Many of these Jews' ancestors passed on the account that they settled in India when the Hebrew King Solomon was in power. This was a time that teak wood, ivory, spices, monkeys, and peacocks were popular in trade in Cochin. There is no specific date or reason mentioned as to why they arrived in India, but Hebrew scholars date it to up to around the early Middle Ages. Cochin is a group of small tropical islands filled with markets and many different cultures such as Dutch, Hindu, Jewish, Portuguese, and British.[22] The distinct Jewish community was called Anjuvannam. The still-functioning synagogue in Mattancherry belongs to the Paradesi Jews, the descendants of Sephardim that were expelled from Spain in 1492,[21] although the Jewish community in Mattancherry adjacent to Fort Cochin had only six remaining members as of 2015.[23]

Central to the history of the Cochin Jews is their close relationship with Indian rulers, and this was eventually codified on a set of copper plates granting the community special privileges. The date of these plates, known as "Sâsanam",[24] is contentious. The plates themselves provide a date of 379 CE, but in 1925, tradition was setting it as 1069 CE,[25] Joseph Rabban by Bhaskara Ravi Varma, the fourth ruler of Maliban granted the copper plates to the Jews. The plates were inscribed with a message stating that the village of Anjuvannam belonged to the Jews and that they were the rightful lords of Anjuvannam and it should remain theirs and be passed on to their Jewish descendants "so long as the world and moon exist". This is the earliest document that shows that the Jews were living in India permanently. It is stored in Cochins main synagogue.[26] The Jews settled in Kodungallur (Cranganore) on the Malabar Coast, where they traded peacefully, until 1524. The Jewish leader Rabban was granted the rank of prince over the Jews of Cochin, given the rulership and tax revenue of a pocket principality in Anjuvannam, near Cranganore, and rights to seventy-two "free houses".[27] The Hindu king gave permission in perpetuity (or, in the more poetic expression of those days, "as long as the world and moon exist") for Jews to live freely, build synagogues, and own property "without conditions attached".[28][29] A link back to Rabban, "the king of Shingly" (another name for Cranganore), was a sign of both purity and prestige. Rabban's descendants maintained this distinct community until a chieftainship dispute broke out between two brothers, one of them named Joseph Azar, in the 16th century. The Jews lived peacefully for over a thousand years in Anjuvannam. After the reign of the Rabban's, the Jewish people no longer had the protection of the copper plates. Neighboring princes of Anjuvannam intervened and revoked all privileges that the Jewish people were given. In 1524, the Jews were attacked by the Moors brothers (Muslim Community) on a suspicion that they were messing with the pepper trade and the homes and synagogues belonging to them were destroyed. The damage was so extensive that when the Portuguese arrived a few years later, only a small amount of impoverished Jews remained. They remained there for 40 more years only to return to their land of Cochin.[26]

In Mala, Thrissur District, the Malabar Jews have a Synagogue and a cemetery, as well as in Chennamangalam, Parur and Ernakulam.[30] There are at least seven existing synagogues in Kerala, although not serving their original purpose anymore.

Madras Jews

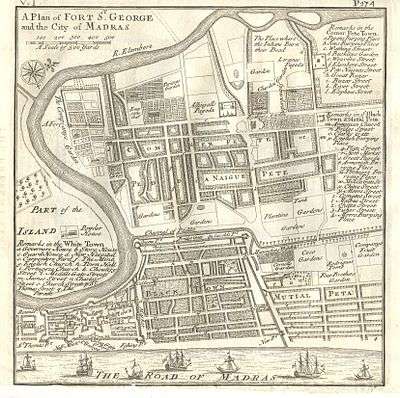

Jews also settled in Madras (now Chennai) soon after its founding in 1640.[31] Most of them were coral merchants from Leghorn, the Caribbean, London, and Amsterdam who were of Portuguese origin and belonged to the Henriques De Castro, Franco, Paiva or Porto families.[31]

Jacques (Jaime) de Paiva (Pavia), originally from Amsterdam belonging to Amsterdam Sephardic community, was an early Jewish arrival and the leader of Madras Jewish community.He built the Second Madras Synagogue and Jewish Cemetery Chennai in Peddanaickenpet, which later became the South end of Mint Street.[32]

Jacques (Jaime) de Paiva (Pavia) established good relations with those in power and bought several Golconda diamonds mines to source Golconda diamonds. Through his efforts, Jews were permitted to live within Fort St. George.[33]

De Paiva died in 1687 after a visit to his mines and was buried in the Jewish cemetery he had established in Peddanaickenpet, which later became the north Mint Street.[33][lower-alpha 1] In 1670, the Portuguese population in Madras numbered around 3000.[35] Before his death he established "The Colony of Jewish Traders of Madraspatam" with Antonio do Porto, Pedro Pereira and Fernando Mendes Henriques.[33] This enabled more Portuguese Jews, from Leghorn, the Caribbean, London and Amsterdam, to settle in Madras. Coral Merchant Street was named after the Jews' business.[36]

Three Portuguese Jews were nominated to be aldermen of Madras Corporation.[37] Three - Bartolomeo Rodrigues, Domingo do Porto and Alvaro da Fonseca - also founded the largest trading house in Madras. The large tomb of Rodrigues, who died in Madras in 1692, became a landmark in Peddanaickenpet, but was later destroyed.[38]

Samuel de Castro came to Madras from Curaçao and Salomon Franco came from Leghorn.[33][39]

In 1688, there were three Jewish representatives in the Madras Corporation.[31] Most Jewish settlers resided in the Coral Merchants Street in Muthialpet.[31] They also had a cemetery, called Jewish Cemetery Chennai in the neighbouring Peddanaickenpet.[31]

Bene Israel

Foreign notices of the Bene Israel go back at least to 1768, when Yechezkel Rahabi wrote to a Dutch trading partner that they were widespread in Maharatta Province, and observed two Jewish observances, recital of the Shema and observation of Shabbat rest.[40] They claim that they descend from 14 Jewish men and women, equally divided by gender, who survived the shipwreck of refugees from persecution or political turmoil, and came ashore at Navagaon near Alibag, 20 miles south of Mumbai, some 17 to 19 centuries ago.[40] They were instructed in the rudiments of normative Judaism by Cochin Jews.[40] Their Jewishness is controversial, and initially was not accepted by the Rabbinate in Israel.[40] Since 1964 however they intermarried throughout Israel and are now considered Israeli and Jewish in all respects.[41]

They are divided into sub-castes which do not intermarry: the dark-skinned "Kara" and fair-skinned "Gora." The latter are believed to be lineal descendants of the shipwreck survivors, while the former are considered to descend from concubinage of a male with local women.[40] They were nicknamed the shanivār telī ("Saturday oil-pressers") by the local population as they abstained from work on Saturdays. Bene Israel communities and synagogues are situated in Pen, Mumbai, Alibag, Pune and Ahmedabad with smaller communities scattered around India. The largest synagogue in Asia outside Israel is in Pune (Ohel David Synagogue).

Mumbai had a thriving Bene Israel community until the 1950s to 1960s when many families from the community emigrated to the fledgling state of Israel, where they are known as Hodi'im (Indians).[40] The Bene Israel community has risen to many positions of prominence in Israel.[42] In India itself the Bene Israel community has shrunk considerably with many of the old Synagogues falling into disuse.

Unlike many parts of the world, Jews have historically lived in India without any instances of anti-Semitism from the local majority populace, the Hindus.[43] However, Jews were persecuted by the Portuguese during their control of Goa.[44]

Bombay/Mumbai

South Asian Jews & Baghdadi Jews

The first known Baghdadi Jewish immigrant to India, Joseph Semah, arrived in the port city of Surat in 1730. He and other early immigrants established a synagogue and cemetery in Surat, though most of the city's Jewish community eventually moved to Bombay (Mumbai), where they established a new synagogue and cemetery. They were traders and quickly became one of the most prosperous communities in the city. As philanthropists, some donated their wealth for public building projects. The Sassoon Docks and David Sassoon Library are some of the famous landmarks still standing today.

The synagogue in Surat was eventually razed; the cemetery, though in poor condition, can still be seen on the Katargam-Amroli road. One of the graves within is that of Moseh Tobi, buried in 1769, who was described as 'ha-Nasi ha-Zaken' (The Elder Prince) by David Solomon Sassoon in his book A History of the Jews in Baghdad (Simon Wallenburg Press, 2006, ISBN 184356002X).

Baghdadi Jewish populations spread beyond Bombay to other parts of India, with an important community forming in Calcutta (Kolkata). Scions of this community did well in trade (particularly jute and tea), and in later years contributed officers to the army. One, Lt-Gen J. F. R. Jacob PVSM, became state governor of Goa (1998–1999), then Punjab, and later served as administrator of Chandigarh. Pramila (Esther Victoria Abraham) became the first ever Miss India, in 1947.

Bnei Menashe

The Bnei Menashe are a group of more than 9,000 people from the northeastern Indian states of Mizoram and Manipur[19] who practice a form of biblical Judaism and claim descent from one of the Lost Tribes of Israel.[45] They were originally headhunters and animists, and converted to Christianity at the beginning of the 20th century, but began converting to Judaism in the 1970s.[46]

Bene Ephraim

The Bene Ephraim are a small group of Telugu-speaking Jews in eastern Andhra Pradesh whose recorded observance of Judaism, like that of the Bnei Menashe, is quite recent, dating only to 1991.[47]

There are a few families in Andhra Pradesh who follow Judaism. Many among them follow the customs of Orthodox Jews, like wearing long beards by men and using head coverings (men) and hair coverings (women) all the time.[48]

Delhi Jewry

Judaism in Delhi is primarily focused on the expatriate community who work in Delhi, as well as Israeli diplomats and a small local community. In Paharganj, Chabad has set up a synagogue and religious center in a backpacker area regularly visited by Israeli tourists.

Today

The majority of Indian Jews have "made Aliyah" (migrated) to Israel since the creation of the modern state in 1948. Over 70,000 Indian Jews now live in Israel (over 1% of Israel's total population). Of the remaining 5,000, the largest community is concentrated in Mumbai, where 3,500 have stayed over from the over 30,000 Jews registered there in the 1940s, divided into Bene Israel and Baghdadi Jews,[49] though the Baghdadi Jews refused to recognize the B'nei Israel as Jews, and withheld dispensing charity to them for that reason.[40] There are reminders of Jewish localities in Kerala still left such as Synagogues. The majority of Jews from the old British-Indian capital of Calcutta (Kolkata) have also migrated to Israel over the last six decades.

Notable Jews of Indian descent

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

- Eli Ben-Menachem, Israeli politician

- Jacqueline Bhabha, lecturer at Harvard Law School and Harvard Kennedy School of Government

- Ranjit Chaudhry (1955 – 2020), Bollywood actor

- Anil Melwin Machado, Yoga & Kalaripayyattu Master.

- David Abraham Cheulkar, Bollywood actor

- Isaac David Kehimkar, lepidopterist, butterfly expert based in Navi Mumbai.

- Reuben David (1912 - 1989) zoologist[50]

- Esther David (March 17, 1945— ), Jewish-Indian author, an artist and a sculptor[51]

- Nadira, Bollywood actress

- Karen David, British-Canadian actress

- Dr Abraham Erulkar, personal physician to Mahatma Gandhi, father of Lila Erulkar

- Lila Erulkar, First Lady of Cyprus (1993–2003) and wife of Glafcos Clerides, president of the Republic of Cyprus

- Nissim Ezekiel, poet, playwright, editor and art-critic

- Lieutenant General J F R Jacob, former Chief of Staff of the Indian Army's Eastern Command, and former Governor of Punjab and Goa

- Vice Admiral Benjamin Abraham Samson, Indian Navy Admiral, former Flag Officer Commanding Indian Fleet

- (Hakham) Ezra Reuben David Barook, a High Priest in Jerusalem in 1856. He travelled to India and settled in Calcutta.[52]

- Gerry Judah, artist and designer

- Ellis Kadoorie and Elly Kadoorie, philanthropists

- Horace Kadoorie, philanthropist

- Anish Kapoor, sculptor

- Aditya Roy Kapur, actor

- Kunaal Roy Kapur, actor

- Siddharth Roy Kapur, film producer

- Samson Kehimkar, musician

- Ezekiel Isaac Malekar, Bene Israel rabbi

- Ruby Myers, Bollywood actress of the 1920s known as Sulochana

- Pearl Padamsee, theatre personality

- Joseph Rabban, was given copper plates of special grants from the Chera ruler Bhaskara Ravivarman II from Kerala

- David and Simon Reuben, businessmen

- Abraham Barak Salem, Cochin Jewish Indian nationalist leader

- Lalchanhima Sailo, rabbi and founder of Chhinlung Israel People's Convention

- David Sassoon, businessman

- Albert Abdullah David Sassoon, British Indian merchant

- Sassoon David Sassoon, philanthropist and benefactor of greater Indian Jewish community

- Solomon Sopher, Jewish community leader in Mumbai

- Bensiyon Songavkar, professional cricketer

- Esther Victoria Abraham, also known as Pramila, first Miss India

- Fleur Ezekiel - Bene Israel model, chosen as Miss World in 1959

- Sheila Singh Paul, paediatrician, founder and director of Kalawati Saran Children's Hospital, New Delhi; pioneer in polio vaccination

- Ruby Daniel, Israeli author of Cochin Jewish origin

- Leela Samson, dancer, choreographer, and actress

- Jael Silliman, Baghdadi Indian Jewish author based in Kolkata

See also

Notes

- A synagogue once also existed at Mint Street.[34]

References

- Sohoni, Pushkar; Robbins, Kenneth X. (2017). Jewish Heritage of the Deccan: Mumbai, the Northern Konkan and Pune. Mumbai: Deccan Heritage Foundation; Jaico. ISBN 9789386348661.

- The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities by Orpa Slapak. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. 2003. p. 27. ISBN 965-278-179-7.

- Weil, Shalva. India's Jewish Heritage: Ritual, Art, and Life-Cycle. Mumbai: Marg Publications [first published in 2002; 3rd edn.]. 2009.

- "Solomon To Cheraman". outlookindia.com.

- Weil, Shalva. "Indian Judaic Tradition" in Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby (eds) Religions in South Asia, London: Palgrave Publishers, 2006. pp. 169-183.

- Weiss, Gary (August 13, 2007). "India's Jews". Forbes. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- Weil, Shalva. "Bene Israel Rites and Routines" in Shalva Weil (ed.) India's Jewish Heritage: Ritual, Art and Life-Cycle, Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2009. [first published in 2002]; 3Arts, 54(2): 26-37.

- Weil, Shalva. (1991) "Beyond the Sambatyon: the Myth of the Ten Lost Tribes." Tel-Aviv: Beth Hatefutsoth, the Nahum Goldman Museum of the Jewish Diaspora.

- Hutchison, Peter (14 January 2018). "Netanyahu trip highlights India's tiny Jewish community". Times of Israel. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Weil, Shalva. "From Persecution to Freedom: Central European Jewish Refugees and their Jewish Host Communities in India" in Anil Bhatti and Johannes H. Voigt (eds) Jewish Exile in India 1933-1945, New Delhi: Manohar and Max Mueller Bhavan,1999. pp. 64-84.

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews", in Judith Baskin (ed.) Cambridge Dictionary of Judaism and Jewish Culture, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011. pp. 107.

- "Foreword - The Last Jews of Cochin: Jewish Identity in Hindu India". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- S. Muthiah (September 30, 2002). "The Hindu : Will Chennai's Jews be there?". www.thehindu.com. Retrieved 2017-01-12.

- Katz 2000; Koder 1973; Thomas Puthiakunnel 1973.

- CafeKK, Team. "Arapalli - The Temple that St. Thomas Built". www.cafekk.com.

- Wolff, Joseph (July 28, 1835). Researches and missionary labours among the Jews, Mohammedans, and other sects. J. Nisbet. p. 469 – via Internet Archive.

nagercoil jews.

- Tyerman, Daniel (July 28, 1841). Voyages and Travels Round the World: By the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennett, Esq. : Deputed from the London Missionary Society to Visit Their Various Stations in the South Sea Islands, China, India, Madagascar, and South Africa Between the Years 1821 and 1829. John Snow. p. 260 – via Internet Archive.

nagercoil jews.

- Weil, Dr. Shalva. "Bene Israel of Mumbai, India". Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Weil, Shalva. "Lost Israelites from North-East India: Re-Traditionalisation and Conversion among the Shinlung from the Indo-Burmese Borderlands." The Anthropologist, 2004. 6(3): 219-233.

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews", in Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember and Ian Skoggard (eds) Encyclopedia of World Cultures Supplement, New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2002. pp. 78-80.

- Schreiber, Mordecai (2003). The Shengold Jewish Encyclopedia. Rockville, MD: Schreiber Publishing. p. 125. ISBN 1887563776.

- Meyer, Raphael. "Jews of India- The Cochin Jews". The-south-asian.

- Pinsker, Alyssa (October 22, 2015). "The last six Paradesi Jews of Cochin". BBC. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- Burnell, Indian Antiquary, iii. 333–334

- Katz, Nathan (2000). Who are the Jews of India?. University of California Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780520213234.

- Meyer, Raphael. "Jews of India-Cochin Jews". The-south-asian.

- taken from WP article on Rabban, which appears to rely on Ken Blady's book Jewish Communities in Exotic Places. Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson Inc., 2000. pp. 115–130. Weil, Shalva. "Symmetry between Christians and Jews in India: the Cnanite Christians and the Cochin Jews of Kerala." Contributions to Indian Sociology, 1982. 16(2): 175-196.

- Three years in America, 1859–1862 (p. 59, p. 60) by Israel Joseph Benjamin

- Roots of Dalit history, Christianity, theology, and spirituality (p. 28) by James Massey, I.S.P.C.K.

- Weil, Shalva. "Where are Cochin Jews today? The Synagogues of Kerala, India." Cochinsyn.com, Friends of Kerala Synagogues. 2011.

- Muthiah, S. (2004). Madras Rediscovered. East West Books (Madras) Pvt Ltd. p. 125. ISBN 81-88661-24-4.

- "The last family of Pardesi Jews in Madras « Madras Musings | We Care for Madras that is Chennai". www.madrasmusings.com. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- Muthiah, S. (3 September 2007). "The Portuguese Jews of Madras". The Hindu. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Sundaram, Krithika (31 October 2012). "18th century Jewish cemetery lies in shambles, craves for attention". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- Parthasarathy, N.S. "The last family of Pardesi Jews in Madras". Madras Musings. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Muthiah, S. (30 September 2002). "Will Chennai's Jews be there?". The Hindu. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- Muthiah, S. (2014). Madras Rediscovered. Westland. ISBN 978-9-38572-477-0.

- Parthasarathy, Anusha (3 September 2013). "Lustre dims, legacy stays". The Hindu. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- "Chennai - India". International Jewish Cemetery Project. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- Nathan Katz, Who Are the Jews of India?, California University Press, 2000 pp.91ff.

- Joseph Hodes,From India to Israel: Identity, Immigration, and the Struggle for Religious Equality, McGill-Queen's Press 2014 pp.98ff.108.

- Weil, Shalva. "Religious Leadership vs. Secular Authority: the Case of the Bene Israel." Eastern Anthropologist, 1996. 49(3- 4): 301-316.

- Weiss, Gary (August 13, 2007). "India's Jews". Forbes. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- Who are the Jews of India? - The S. Mark Taper Foundation imprint in Jewish studies. University of California Press. 2000. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-520-21323-4.; "When the Portuguese arrived in 1498, they brought a spirit of intolerance utterly alien to India. They soon established an Office of Inquisition at Goa, and at their hands, Indian Jews experienced the only instance of anti-Semitism ever to occur in Indian soil."

- Stephen Epstein. "Bnei Menashe History". Bneimenashe.com. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- "More than 7,200 Indian Jews to immigrate to Israel". The Times Of India. September 27, 2011.

- Egorova, Yulia; Perwez, Shahid (30 August 2012). "View of Telugu Jews: Are the Dalits of coastal Andhra going caste-awry?". South Asianist. 1 (1): 7–16.

- Yulia Egorova and Shahid Perwez (2011). "Kulanu: The Bene Ephraim of Andhra Pradesh, India". Kulanu.org. Archived from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- Rachel Delia Benaim, 'For India's Largest Jewish Community, One Muslim Makes All the Tombstones,' Tablet 23 February 2015.

- "Reuben David". estherdavid.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009.

- Weil, Shalva. "Esther David: The Bene Israel Novelist who Grew Up with a Tiger" in David Shulman and Shalva Weil (eds) Karmic Passages: Israeli Scholarship on India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008. pp. 232-253.

- Rabbi Ezekiel Nissim Musleah. Author of "On the banks of the Ganga: The sojourn of Jews in Calcutta"

Further reading

- Aafreedi, Navras Jaat, ed., Café Dissensus, Issue 12: Indian Jewry, January 2015

- Aafreedi, Navras Jaat, "Community and Belonging in Indian Jewish Literature", Himal Southasian (ISSN 1012-9804), May 2014

- Aafreedi, Navras Jaat, "Absence of Jewish Studies in India: Creating A New Awareness", Asian Jewish Life (ISSN 2224-3011), Autumn 2010, pp. 31–34.

- Aafreedi, Navras Jaat, "Jewish-Muslim Relations in South Asia: Where Antipathy lives without Jews", Asian Jewish Life (ISSN 2224-3011), Issue 15, October 2014, pp. 13–16.

- Aafreedi, Navras Jaat, "The Attitudes of Lucknow's Muslims towards Jews, Israel and Zionism", Café Dissensus (ISSN 2373-177X), Issue 7, April 15, 2014

- Aafreedi, Navras Jaat, "History of India's Jewish Beauty Queens", Yedioth Ahronoth, August 3, 2013

- Aafreedi, Navras Jaat, "Hindi Novel Portrays Life of Indian Jews", Yedioth Ahronoth, May 23, 2013

- India's Bene Israel: A Comprehensive Inquiry and Sourcebook Isenberg, Shirley Berry; Berkeley: Judah L. Magnes Museum, 1988

- Indian Jewish Heritage: Ritual, Art and Life-Cycle Dr. Shalva Weil (ed). Mumbai: Marg Publications, 3rd ed. 2009

- Indo-Judaic Studies in the Twenty-First Century: A Perspective from the Margin, Katz N., Chakravarti, R., Sinha, B. M. and Weil, S., New York and Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan. 2007

- Karmic Passages: Israeli Scholarship on India, Shulman, D. and Weil, S. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.2008

- The Last Jews of Kerala, Edna Fernandes, Portobello Books, (ISBN 978-1-84627-099-4), 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Judaism in India. |

- INDIA Encyclopaedia Judaica article in Encyclopedia.com

- Jews Of India Encyclopedia of India article in Encyclopedia.com

- TheJewsOfIndia.com Comprehensive website of Jews in India

- Bneimenashe.com, Bnei Menashe Jews of North East India

- Haruth.com Jewish India

- Jewsofindia.org Jews of India

- Indjews.com, Indian synagogues in Israel

- Indian Jews - Jewish Encyclopedia

- Bene Israel - Jewish Encyclopedia

- Cochin Jews - Jewish Encyclopedia

- Calcutta Jews - Jewish Encyclopedia

- India Virtual Jewish History Tour - Jewish Virtual Library

- Information on synagogues in Kerala, India