Cochin Jews

Cochin Jews (also known as Malabar Jews or Kochinim, from Hebrew: יהודי קוצ'ין Yehudey Kochin) are the oldest group of Jews in India, with roots that are claimed to date back to the time of King Solomon.[2][3] The Cochin Jews settled in the Kingdom of Cochin in South India,[4] now part of the state of Kerala.[5][6] As early as the 12th century, mention is made of the Jews in southern India. The Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela, speaking of Kollam (Quilon) on the Malabar Coast, writes in his Itinerary:

"...throughout the island, including all the towns thereof, live several thousand Israelites. The inhabitants are all black, and the Jews also. The latter are good and benevolent. They know the law of Moses and the prophets, and to a small extent the Talmud and Halacha."[7]

יהודי קוצ'ין കൊച്ചിയിലെ ജൂതന്മാർ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 7,000–8,000 (estimated)[1] | |

| 26 | |

| Languages | |

| Hebrew, Judeo-Malayalam | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Paradesi Jews, Sephardic Jews, Bene Israel, Baghdadi Jews, Mizrahi Jews | |

These people later became known as the Malabari Jews. They built synagogues in Kerala beginning in the 12th and 13th centuries.[8][9] They are known to have developed Judeo-Malayalam, a dialect of Malayalam language.

Following their expulsion from Iberia in 1492 by the Alhambra Decree, a few families of Sephardi Jews eventually made their way to Cochin in the 16th century. They became known as Paradesi Jews (or Foreign Jews). The European Jews maintained some trade connections to Europe, and their language skills were useful. Although the Sephardim spoke Ladino (i. e., Spanish or Judeo-Spanish), in India they learned Judeo-Malayalam from the Malabar Jews.[10] The two communities retained their ethnic and cultural distinctions.[11] In the late 19th century, a few Arabic-speaking Jews, who became known as Baghdadi, also immigrated to southern India, and joined the Paradesi community.

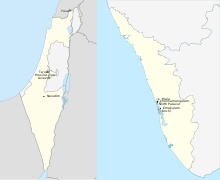

After India gained its independence in 1947 and Israel was established as a nation, most of the Malabar Jews made Aliyah and emigrated from Kerala to Israel in the mid-1950s. In contrast, most of the Paradesi Jews (Sephardi in origin) preferred to migrate to Australia and other Commonwealth countries, similar to the choices made by Anglo-Indians.[12]

Most of their synagogues are still existing in Kerala, whereas a few were sold or adapted for other uses. Among the 8 synagogues that had survived till the middle of 20th century, only the Paradesi synagogue still has a regular congregation and also attracts tourists as a historic site. Another synagogue at Ernakulam operates partly as a shop by one of few remaining Cochin Jews. A few synagogues are in ruins and one was even demolished and a two-storeyed house was built in its place. The synagogue at Chendamangalam (Chennamangalam) was reconstructed in 2006 as Kerala Jews Life Style Museum.[13] The synagogue at Paravur (Parur) has been reconstructed as Kerala Jews History Museum.[14][15]

History

First Jews in South India

.png)

P. M. Jussay wrote that it was believed that the earliest Jews in India were sailors from King Solomon's time.[16] It has been claimed that following the destruction of the First Temple in the Siege of Jerusalem of 587 BCE, some Jewish exiles came to India.[17] Only after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE are records found that attest to numerous Jewish settlers arriving at Cranganore, an ancient port near Cochin.[18] Cranganore, now transliterated as Kodungallur, but also known under other names, is a city of legendary importance to this community. Fernandes writes, it is "a substitute Jerusalem in India".[19] Katz and Goldberg note the "symbolic intertwining" of the two cities.[20]

In 1768, a certain Tobias Boas of Amsterdam had posed eleven questions to Rabbi Yehezkel Rachbi of Cochin. The first of these questions addressed to the said Rabbi concerned the origins of the Jews of Cochin and the duration of their settlement in India. In Rabbi Yehezkel's hand written response (Merzbacher's Library in Munich, MS. 4238), he wrote: "...after the destruction of the Second Temple (may it soon be rebuilt and reestablished in our days!), in the year 3828 of anno mundi, i. e., 68 CE, about ten thousand men and women had come to the land of Malabar and were pleased to settle in four places; those places being Cranganore, Dschalor, [21] Madai[22] [and] Plota.[23] Most were in Cranganore, which is also called Mago dera Patinas; it is also called Sengale."[24][25]

Saint Thomas, an Aramaic-speaking[26] Jew from the Galilee region of Israel and one of the disciples of Jesus, is believed to have come to Southern India[27] in the 1st century, in search of the Jewish community there.[28][29][30] It is possible that the Jews who became Christians at that time were absorbed by what became the Nasrani Community in Kerala.[28][30][31]

Central to the history of the Cochin Jews was their close relationship with Indian rulers. This was codified on a set of copper plates granting the community special privileges.[32] The date of these plates, known as "Sâsanam",[33] is contentious. The plates are physically inscribed with the date 379 CE,[34][35] but in 1925, tradition was setting it as 1069 CE.[36] Indian rulers granted the Jewish leader Joseph Rabban the rank of prince over the Jews of Cochin, giving him the rulership and tax revenue of a pocket principality in Anjuvannam near Cranganore, and rights to seventy-two "free houses".[37] The Hindu king gave permission in perpetuity (or, in the more poetic expression of those days, "as long as the world and moon exist") for Jews to live freely, build synagogues, and own property "without conditions attached".[38][39] A family connection to Rabban, "the king of Shingly" (another name for Cranganore), was long considered a sign of both purity and prestige within the community. Rabban's descendants led this distinct community until a chieftainship dispute broke out between two brothers, one of them named Joseph Azar, in the 16th century.[40]

The oldest known gravestone of a Cochin Jew is written in Hebrew and dates to 1269 CE. It is near the Chendamangalam (also spelled Chennamangalam) Synagogue, built in 1614,[8] which is now operated as a museum.[41]

In 1341, a disastrous flood silted up the port of Cranganore, and trade shifted to a smaller port at Cochin (Kochi). Many of the Jews moved quickly, and within four years, they had built their first synagogue at the new community.[42] The Portuguese Empire established a trading beachhead in 1500, and until 1663 remained the dominant power. They continued to discriminate against the Jews, although doing business with them. A synagogue was built at Parur in 1615, at a site that according to tradition had a synagogue built in 1165. Almost every member of this community emigrated to Israel in 1954.[8]

In 1524, the Muslims, backed by the ruler of Calicut (today called Kozhikode and not to be confused with Calcutta), attacked the wealthy Jews of Cranganore because of their primacy in the lucrative pepper trade. The Jews fled south to the Kingdom of Cochin, seeking the protection of the Cochin Royal Family (Perumpadapu Swaroopam). The Hindu Raja of Cochin gave them asylum. Moreover, he exempted Jews from taxation but bestowed on them all privileges enjoyed by the tax-payers.[43]

The Malabari Jews built additional synagogues at Mala and Ernakulam. In the latter location, Kadavumbagham Synagogue was built about 1200 and restored in the 1790s. Its members believed they were the congregation to receive the historic copper plates. In the 1930s and 1940s, the congregation was as large as 2,000 members, but all emigrated to Israel.[44]

Thekkambagham Synagogue was built in Ernakulum in 1580, and rebuilt in 1939. It is the synagogue in Ernakulam sometimes used for services if former members of the community visit from Israel. In 1998, five families who were members of this congregation still lived in Kerala or in Madras.[45]

A Jewish traveler's visit to Cochin

The following is a description of the Jews of Cochin by 16th-century Jewish traveler Zechariah Dhahiri (recollections of his travels in circa 1558).

I travelled from the land of Yemen unto the land of India and Cush, in order to search out a better livelihood. I had chosen the frontier route, where I made a passage across the Great Sea by ship for twenty days... I arrived at the city of Calicut, which upon entering I was sorely grieved at what I had seen, for the city’s inhabitants are all uncircumcised and given over to idolatry. There isn’t to be found in her a single Jew with whom I could have, otherwise, taken respite in my journeys and wanderings. I then turned away from her and went into the city of Cochin, wherein I found what my soul desired, insofar that a community of Spaniards is to be found there who are derived of Jewish lineage, along with other congregations of proselytes.[46] They had been converted many years ago, of the natives of Cochin and Germany.[47] They are adept in their knowledge of Jewish laws and customs, acknowledging the injunctions of the Divine Law (Torah), and making use of its means of punishment. I dwelt there three months, among the holy congregations.[48]

1660 to independence

The Paradesi Jews, also called "White Jews", settled in the Cochin region in the 16th century and later, following the expulsion from Iberia due to forced conversion and religious persecution in Spain and then Portugal. Some fled north to Holland but the majority fled east to the Ottoman Empire.

Some went beyond that territory, including a few families who followed the Arab spice routes to southern India. Speaking Ladino language and having Sephardic customs, they found the Malabari Jewish community as established in Cochin to be quite different. According to the historian Mandelbaum, there were resulting tensions between the two ethnic communities.[49] The European Jews had some trade links to Europe and useful languages to conduct international trade,[11] i. e., Arabic, Portuguese, and Spanish, later on maybe Dutch. These attributes helped their position both financially and politically.

When the Portuguese occupied the Kingdom of Cochin, they allegedly discriminated against its Jews. Nevertheless, to some extent they shared language and culture, so ever more Jews came to live under Portuguese rule (actually under the Spanish crown, again, between 1580 and 1640). The Protestant Dutch killed the raja of Cochin, allied of the Portuguese, plus sixteen hundred Indians in 1662, during their siege of Cochin. The Jews, having supported the Dutch military attempt, suffered the murderous retaliation of both Portuguese and Malabar population. A year later, the second Dutch siege was successful and, after slaughtering the Portuguese, they demolished most Catholic churches or turned them into Protestant churches (not sparing the one where Vasco da Gama had been buried). They were more tolerant of Jews, having granted asylum claims in the Netherlands. (See the Goa Inquisition for the situation in nearby Goa.) This attitude differs with the antisemitism of the Dutch in New York under Pieter Stuyvesand around those years.

The Malabari Jews (referred to historically during the colonial years as Black, although their skin colour was brown) built seven synagogues in Cochin, reflecting the size of their population.

The Paradesi Jews (also called White Jews) built one, the Paradesi Synagogue. The latter group was very small by comparison to the Malabaris. Both groups practiced endogamous marriage, maintaining their distinctions. Both communities claimed special privileges and the greater status over each other.[50]

It is claimed that the White Jews had brought with them from Iberia a few score meshuchrarim (former slaves, some of mixed African-European descent). Although free, they were relegated to a subordinate position in the community. These Jews formed a third sub-group within Cochin Jewry. The meshuchrarim were not allowed to marry White Jews and had to sit in the back of the synagogue; these practices were similar to the discrimination against converts from lower castes sometimes found in Christian churches in India.

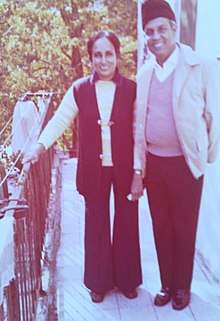

In the early 20th century, Abraham Barak Salem (1882–1967), a young lawyer who became known as a "Jewish Gandhi", worked to end the discrimination against meshuchrarim Jews. Inspired by Indian nationalism and Zionism, he also tried to reconcile the divisions among the Cochin Jews.[51] He became both an Indian nationalist and Zionist. His family were descended from meshuchrarim. The Hebrew word denoted a manumitted slave, and was at times used in a derogatory way. Salem fought against the discrimination by boycotting the Paradesi Synagogue for a time. He also used satyagraha to combat the social discrimination. According to Mandelbaum, by the mid-1930s many of the old taboos had fallen with a changing society.[52]

The Cochini Anjuvannam Jews also migrated to Malaya. Records show that they settled in Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. The last descendant of Cochin Jews in Seremban is Benjamin Meyuhasheem.

Relations between the Cochin Jews, Madras Jews, and Bene-Israel

Although India is noted for having four distinct Jewish communities, viz Cochin, Bene-Israel (of Bombay and its environs), Calcutta and New Delhi, communications between the Jews of Cochin and the Bene-Israel community were greatest in the mid-19th century.[53] According to native Bene Israel historian Haeem Samuel Kehimkar (1830-1909), several prominent members from the "White Jews" of Cochin had moved to Bombay in 1825 from Cochin, of whom are specifically named Michael and Abraham Sargon, David Baruch Rahabi, Hacham Samuel and Judah David Ashkenazi. These exerted themselves not only in changing the minds of the Bene-Israel and of their children generally, but also particularly in turning the minds of these few of the Bene-Israel, who through heathen influence had gone astray from the path of the religion of their forefathers, to the study of their own religion, and to the contemplation on Yahweh. David Rahabi was effected a religious revival at Revandanda, followed by his successor Hacham Samuel.[54] Although David Rahabi was convinced that the Bene Israel were the descendants of the Jews, he still wanted to examine them further. He therefore gave their women clean and unclean fish to be cooked together, but they singled out the clean from the unclean ones, saying that they never used fish that had neither fins nor scales. Being thus satisfied, he began to teach them the tenets of the Jewish religion. He taught Hebrew reading, without translation, to three Bene-Israel young men from the families of Jhiratker, Shapurker and Rajpurker.[55] David Rahabi is said to have been killed as a martyr in India, two or three years after coming upon the Bene-Israel, by a local chief.

Another influential man from Cochin, who is alleged to have been of Yemenite Jewish origin, was Hacham Shellomo Salem Shurrabi who served as a Hazan (Reader) in the then newly formed synagogue of the Bene-Israel in Bombay for the trifling sum of 100 rupees per annum, although he worked also as a book-binder. While engaged in his avocation, he was at all times ready to explain any scriptural difficulty that might happen to be brought to him by any Bene-Israel. He was a Reader, Preacher, Expounder of the Law, Mohel and Shochet.[56] He served the community for about 18 years, and died on 17 April 1856.

Since 1947

Along with China and Georgia, India is one of the only parts of Eurasia where anti-Semitism never took root, in spite of having a sizable Jewish population in the past. India became independent from British occupation in 1947 and Israel established itself as a nation in 1948. With the heightened emphasis on the Partition of India into a secular Republic of India and a semi-theocratic Pakistan, most of the Cochin Jews emigrated from India. Generally they went to Israel (made aliyah).

Many of the migrants joined the moshavim (agricultural settlements) of Nevatim, Shahar, Yuval, and Mesilat Zion.[12] Others settled in the neighbourhood of Katamon in Jerusalem, and in Beersheba, Ramla, Dimona, and Yeruham, where many Bene Israel had settled.[57] Since the late 20th century, former Cochin Jews have also immigrated to the United States.

In Cochin, the Paradesi Synagogue is still active as a place of worship, but the Jewish community is very small. The building also attracts visitors as a historic tourist site. As of 2008, the ticket-seller at the synagogue, Yaheh Hallegua, is the last female Paradesi Jew of child-bearing age in the community.[58]

Genetic analysis

Genetic testing into the origins of the Cochin Jewish and other Indian Jewish communities noted that until the present day the Indian Jews maintained in the range of 3%-20% Middle Eastern ancestry, confirming the traditional narrative of migration from the Middle East to India. The tests noted however that the communities had considerable Indian admixture, exhibiting the fact that the Indian Jewish people "inherited their ancestry from Middle Eastern and Indian populations".[59]

Traditions and way of life

.jpg)

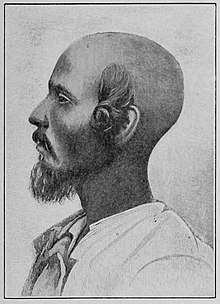

The 12th-century Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela wrote about the Malabari coast of Kerala: "They know the law of Moses and the prophets, and to a small extent the Talmud and Halacha."[60] European Jews sent texts to the community of Cochin Jews to teach them about normative Judaism.

Maimonides (1135–1204), the preeminent Jewish philosopher of his day, wrote,

"Only lately, some well-to-do men came forward and purchased three copies of my code [the Mishneh Torah], which they distributed through messengers... Thus, the horizon of these Jews was widened, and the religious life in all communities as far as India revived."[61]

In a 1535 letter sent from Safed, Israel, to Italy, David del Rossi wrote that a Jewish merchant from Tripoli had told him the India town of Shingly (Cranganore) had a large Jewish population who dabbled in yearly pepper trade with the Portuguese. As far as their religious life, he wrote that they "only recognize the Code of Maimonides, and possessed no other authority or Traditional law".[62] According to the contemporary historian Nathan Katz, Rabbi Nissim of Gerona (the Ran) visited the Cochini Jews. They preserve in their song books the poem he wrote about them.[63] In the Kadavumbagham synagogue, a Hebrew school was available for both "children's education and adult study of Torah and Mishnah".[64]

The Jewish Encyclopedia (1901-1906) said,

"Though they neither eat nor drink together, nor intermarry, the Black and the White Jews of Cochin have almost the same social and religious customs. They hold the same doctrines, use the same ritual (Sephardic), observe the same feasts and fasts, dress alike, and have adopted the same language Malayalam. ... The two classes are equally strict in religious observances",[65]

According to, Martine Chemana, the Jews of Cochin "coalesced around the religious fundamentals: devotion and strict obedience to Biblical Judaism, and to the Jewish customs and traditions ... Hebrew, taught through the Torah texts by rabbis and teachers who came especially from Yemen..."[66]

The Jews of Cochin had a long tradition of singing devotional hymns (piyyutim) and songs on festive occasions, as well as women singing Jewish prayers[67][68] and narrative songs in Judeo-Malayalam; they did not adhere to the Talmudic prohibition against public singing by women (kol isha).[66][69][70]

Cochin Jewish surnames

| List of Cochin Jewish surnames (partial) |

|---|

|

See also

- List of Synagogues in Kerala

- History of the Jews in India

- Gathering of Israel

- Judaism

- Anjuvannam

Notes

- "Jews from Cochin Bring Their Unique Indian Cuisine to Israeli Diners", Tablet Magazine, by Dana Kessler, 23 October 2013

- The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities by Orpa Slapak. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. 2003. p. 27. ISBN 965-278-179-7.

- Weil, Shalva. "Jews in India." in M. Avrum Erlich (ed.) Encyclopaedia of the Jewish Diaspora, Santa Barbara, USA: ABC CLIO. 2008, 3: 1204-1212.

- Weil, Shalva. India's Jewish Heritage: Ritual, Art, and Life-Cycle, Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2009. [first published in 2002; 3rd edn] Katz 2000; Koder 1973; Menachery 1998

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews", in Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember and Ian Skoggard (eds) Encyclopedia of World Cultures Supplement, New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2002. pp. 78-80.

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews" in Judith Baskin (ed.) Cambridge Dictionary of Judaism and Jewish Culture, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011. pp. 107.

- The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela (ed. Marcus Nathan Adler), Oxford University Press, London 1907, p. 65

- Weil, Shalva. From Cochin to Israel. Jerusalem: Kumu Berina, 1984. (Hebrew)

- Weil, Shalva. "Kerala to restore 400-year-old Indian synagogue", The Jerusalem Post. 2009.

- Katz 2000; Koder 1973; Thomas Puthiakunnel 1973.

- Weil, Shalva. "The Place of Alwaye in Modern Cochin Jewish History", Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 2010. 8(3): 319-335.

- Weil, Shalva. From Cochin to Israel, Jerusalem: Kumu Berina, 1984. (Hebrew)

- Weil, Shalva (with Jay Waronker and Marian Sofaer) The Chennamangalam Synagogue: Jewish Community in a Village in Kerala. Kerala: Chennamangalam Synagogue, 2006.

- "The Synagogues of Kerala, India: Architectural and Cultural Heritage." Cochinsyn.com, Friends of Kerala Synagogues, 2011.M

- Weil, Shalva. "In an Ancient Land: Trade and synagogues in south India", Asian Jewish Life. 2011.

- The Jews of Kerala, P. M. Jussay, cited in The Last Jews of Kerala, p. 79

- The Last Jews of Kerala, p. 98

- Katz 2000; Koder 1973; Thomas Puthiakunnel 1973; David de Beth Hillel, 1832; Lord, James Henry 1977.

- The Last Jews of Kerala, p. 102

- The Last Jews of Kerala, p. 47

- Place unidentified; possibly Keezhallur in Kerala State.

- Place unidentified; poss. Madayikonan in Kerala State.

- Place unidentified; poss. Palode in Kerala State.

- J. Winter and Aug. Wünsche, Die Jüdische Literatur seit Abschluss des Kanons, vol. iii, Hildesheim 1965, pp. 459-462 (German)

- A similar tradition has been preserved by David Solomon Sassoon, where he mentions the first places of Jewish settlement on the Malabar Coast as Cranganore, Madai, Pelota and Palur, which were then under the rule of the Perumal dynasty. See: David Solomon Sassoon, Ohel Dawid (Descriptive catalogue of the Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts in the Sassoon Library, London), vol. 1, Oxford Univ. Press: London 1932, p. 370, section 268

- "Aramaic language". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "BENEDICT XVI, GENERAL AUDIENCE, Saint Peter's Square: Thomas the twin". w2.vatican.va. 27 September 2006. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Puthiakunnel, Thomas (1973). "Jewish colonies of India paved the way for St. Thomas". In Menachery, George (ed.). The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India. Volume 2. Trichur. OCLC 1237836.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Slapak, Orpa, ed. (2003). The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. p. 27. ISBN 965-278-179-7 – via University Press of New England.

- India and St.Thomas > South Indian Mission >Overview at the Wayback Machine (archived 2011-06-07)

- Muthiah, S. (1999). Madras Rediscovered: A Historical Guide to Looking Around, Supplemented with Tales of 'Once Upon a City'. East West Books. p. 113. ISBN 818-685-222-0.

- Weil, Shalva. "Symmetry between Christians and Jews in India: the Cnanite Christians and the Cochin Jews of Kerala", Contributions to Indian Sociology, 1982. 16(2): 175-196.

- Burnell, Indian Antiquary, iii. 333–334

- Haeem Samuel Kehimkar, The History of the Bene-Israel of India (ed. Immanuel Olsvanger), Tel-Aviv : The Dayag Press, Ltd.; London : G. Salby 1937, p. 64

- David Solomon Sassoon, Ohel Dawid (Descriptive catalogue of the Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts in the Sassoon Library, London), vol. 1, Oxford Univ. Press: London 1932, p. 370, section 268. According to David Solomon Sassoon, the copper plates were inscribed during the period of the last ruler of the Perumal dynasty, Shirman Perumal.

- Katz, Nathan (2000). Who are the Jews of India?. University of California Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780520213234.

- Ken Blady, Jewish Communities in Exotic Places. Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson Inc., 2000. pp. 115–130. Weil, Shalva. "Jews of India" in Raphael Patai and Haya Bar Itzhak (eds.) Jewish Folklore and Traditions: A Multicultural Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, Inc. 2013, (1: 255-258).

- Three Years in America, 1859–1862, (p. 59, p. 60) by Israel Joseph Benjamin

- Roots of Dalit History, Christianity, Theology, and Spirituality (p. 28) by James Massey, I.S.P.C.K.

- Mendelssohn, Sidney (1920). The Jews of Asia: Especially in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. AMS Press. p. 109.

- The Last Jews of Kerala, pp. 81–82 Weil, Shalva (with Jay Waronker and Marian Sofaer) The Chennamangalam Synagogue: Jewish Community in a Village in Kerala. Kerala: Chennamangalam Synagogue, 2006.

- The Last Jews of Kerala p. 111 Weil, Shalva. "The Place of Alwaye in Modern Cochin Jewish History." Journal of Modern Jewish Studies. 2010, 8(3): 319-335.

- Who Are the Jews of India? (pp. 34-35) Nathan Katz

- Weil, Shalva. From Cochin to Israel. Jerusalem: Kumu Berina, 1984. (Hebrew)

- Weil, Shalva. "A Revival of Jewish Heritage on the Indian Tourism Trail". Jerusalem Post Magazine, 16 July 2010. pp. 34-36.

- This view is supported by Rabbi Yehezkel Rachbi of Cochin who, in a letter addressed to Tobias Boas of Amsterdam in 1768, wrote: "We are called 'White Jews', being people who have come from the Holy Land, (may it be built and established quickly, even in our days), while the Jews that are called 'Black' they became such in Malabar from proselytization and emancipation. However, their status and their rule of law, as well as their prayer, are just as ours." See: Sefunot, Book One (article: "Sources for the History on the Relations Between the White and Black Jews of Cochin"), p. רמט, but in PDF p. 271 (Hebrew)

- Excursus: The word used here in the Hebrew original is “Kena`anim,” typically translated as “Canaanites.” Etymologically, it is important to point out that during the Middle-Ages amongst Jewish scholars, the word “Kena`ani” had taken on the connotation of “German,” or resident of Germany (Arabic: Alemania), which usage would have been familiar to our author, Zechariah al-Dhahiri. Not that the Germans are really derived from Canaan, since this has been refuted by later scholars, but only for the sake of clarity of intent do we make mention of this fact. Al-Dhahiri knew, just as we know today, that German Jews had settled in Cochin, the most notable families of which being Rottenburg and Ashkenazi, among others. In Ibn Ezra’s commentary on Obadiah 1:20, he writes: “Who are [among] the Canaanites. We have heard from great men that the land of Germany (Alemania) they are the Canaanites who fled from the children of Israel when they came into the country.” Rabbi David Kimchi (1160–1235), in his commentary on Obadiah 1:20, writes similarly: “...Now they say by way of tradition that the people of the land of Germany (Alemania) were Canaanites, for when the Canaanite [nation] went away from Joshua, just as we have written in the Book of Joshua, they went off to the land of Germany (Alemania) and Escalona, which is called the land of Ashkenaz, while unto this day they are called Canaanites.” Notwithstanding, the editor Yehuda Ratzaby, in his Sefer Hamussar edition (published in 1965 by the Ben Zvi Institute in Jerusalem), thought that Zechariah al-Dhahiri’s intention here was to “emancipated Canaanite slaves,” in which case, he takes the word literally as meaning Canaanite. Still, his view presents no real problem, since in Hebrew parlance, a Canaanite slave is a generic term which can also apply to any domestic slave derived from other nations as well and which are held by the people of Israel. Conclusion: According to al-Dhahiri, he saw the German Jews in Cochin as being descendants of German proselytes.

- Al-Dhahiri, Zechariah. "Sefer Ha-Musar". (ed. Mordechai Yitzhari), Bnei Barak 2008, p. 67 (Hebrew). Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Cited on p 51 in The Last Jews of Kerala

- "Cochin Jews" Indian Express, accessed 13 December 2008

- "A Kochi dream died in Mumbai". Indian Express, 13 December 2008

- Katz, The Last Jews of Kerala, p. 164

- "The Last Jews of Cochin". Pacific Standard. 21 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- Haeem Samuel Kehimkar, The History of the Bene-Israel of India (ed. Immanuel Olsvanger), Tel-Aviv : The Dayag Press, Ltd.; London : G. Salby 1937, p. 66

- Haeem Samuel Kehimkar, A sketch of the history of Bene-Israel : and an appeal for their education, Bombay : Education Society's Press 1892, p. 20

- Haeem Samuel Kehimkar, The History of the Bene-Israel of India (ed. Immanuel Olsvanger), Tel-Aviv : The Dayag Press, Ltd.; London : G. Salby 1937, pp. 67-68

- Shulman, D. and Weil, S. (eds). Karmic Passages: Israeli Scholarship on India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Abram, David (November 2010). The Rough Guide to Kerala (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-84836-541-4.

- Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Singh, Manvendra; Rai, Niraj; Kariappa, Mini; Singh, Kamayani; Singh, Ashish; Pratap Singh, Deepankar; Tamang, Rakesh; Selvi Rani, Deepa; Reddy, Alla G.; Kumar Singh, Vijay; Singh, Lalji; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy (13 January 2016). "Genetic affinities of the Jewish populations of India". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 19166. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619166C. doi:10.1038/srep19166. PMC 4725824. PMID 26759184.

- Adler, Marcus Nathan (1907). "The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela: Critical Text, Translation and Commentary". Depts.washington.edu. New York: Phillip Feldheim, Inc. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Twersky, Isadore. A Maimonides Reader. Behrman House. Inc., 1972, pp. 481–482

- Katz, Nathan and Ellen S. Goldberg. The Last Jews of Cochin: Jewish Identity in Hindu India. University of South Carolina Press, p. 40. Also, Katz, Nathan, Who Are the Jews of India?, University of California Press, 2000, p. 33.

- Katz, Who Are the Jews of India?, op. cit., p. 32.

- "ISJM Jewish Heritage Report Volume II, nos 3-4". 25 January 1999. Archived from the original on 15 May 2001.

- "Jacobs, Joseph and Joseph Ezekiel. "Cochin", 1901–1906, pp. 135–138". Jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Chemana, Martine (15 October 2002). "Les femmes chantent, les hommes écoutent.. Chants en malayalam (pattu-kal) des Kochini, communautés juives du Kerala, en Inde et en Israël" [Women sing, men listen: Malayalam folksongs of the Cochini, the Jewish Community of Kerala, in India and in Israel]. Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem (in French) (11): 28–44.

- Weil, Shalva (2006). "Today is Purim: A Cochin Jewish Song in Hebrew". TAPASAM Journal: Quarterly Journal for Kerala Studies. 1 (3): 575–588.

- Weil, Shalva; Timberg, T.A. (2008). "Jews in India". In Erlich, M.Avrum (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Jewish Diaspora. 3. Barbara, USA: ABC CLIO. pp. 1204–1212.

- Pradeep, K. (15 May 2005). "Musical Heritage". The Hindu. Hindu.com. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Johnson, Barbara C. (1 March 2009). "Cochin: Jewish Women's Music". Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

References

- Fernandes, Edna. (2008) The Last Jews of Kerala. London: Portobello Books. ISBN 978-1-84627-098-7

- Koder, S. "History of the Jews of Kerala", The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India, ed. G. Menachery, 1973.

- Puthiakunnel, Thomas. (1973) "Jewish Colonies of India Paved the Way for St. Thomas", The Saint Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India, ed. George Menachery, Vol. II., Trichur.

- Daniel, Ruby & B. Johnson. (1995). Ruby of Cochin: An Indian Jewish Woman Remembers. Philadelphia and Jerusalem: Jewish Publication Society.

- Day, Francis (1869). The Land of the Permauls, Or, Cochin, Its Past and Its Present, Cochin Jewish life in 18th century, read Chapter VIII (pp. 336 to 354), reproduced pp. 446-451 in ICHC I, 1998, Ed. George Menachery. Francis Day was a British civil surgeon in 1863.

- Walter J. Fischel, The Cochin Jews, reproduced from the Cochin Synagogue, 4th century, Vol. 1968, Ed. Velayudhan and Koder, Kerala History Association, Ernakulam, reproduced in ICHC I, Ed. George Menachery, 1998, pp. 562–563

- de Beth Hillel, David. (1832) Travels; Madras.

- Gamliel, Ophira (April 2009). Jewish Malayalam Women's Songs (PDF) (PhD). Hebrew University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Jussay, P.M. (1986) "The Wedding Songs of the Cochin Jews and of the Knanite Christians of Kerala: A Study in Comparison". Symposium.

- Jussay, P. M. (2005). The Jews of Kerala. Calicut: Publication division, University of Calicut.

- Hough, James. (1893) The History of Christianity in India.

- Lord, James Henry. (1977) The Jews in India and the Far East. 120 pp.; Greenwood Press Reprint; ISBN 0-8371-2615-0

- Menachery, George, ed. (1998) The Indian Church History Classics, Vol. I, The Nazranies, Ollur, 1998. ISBN 81-87133-05-8

- Katz, Nathan; & Goldberg, Ellen S; (1993) The Last Jews of Cochin: Jewish Identity in Hindu India. Foreword by Daniel J. Elazar, Columbia, SC: Univ. of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-847-6

- Menachery, George, ed. (1973) The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India B.N.K. Press, vol. 2, ISBN 81-87132-06-X, Lib. Cong. Cat. Card. No. 73-905568 ; B.N.K. Press

- Weil, Shalva (25 July 2016). "Symmetry between Christians and Jews in India: the Cnanite Christians and the Cochin Jews of Kerala". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 16 (2): 175–196. doi:10.1177/006996678201600202.

- Weil, Shalva. From Cochin to Israel. Jerusalem: Kumu Berina, 1984. (Hebrew)

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews", in Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember and Ian Skoggard (eds) Encyclopedia of World Cultures Supplement, New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2002. pp. 78–80.

- Weil, Shalva. "Jews in India." in M.Avrum Erlich (ed.) Encyclopaedia of the Jewish Diaspora, Santa Barbara, USA: ABC CLIO. 2008, 3: 1204-1212.

- Weil, Shalva. India's Jewish Heritage: Ritual, Art and Life-Cycle, Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2009. [first published in 2002; 3rd edn.].

- Weil, Shalva. "The Place of Alwaye in Modern Cochin Jewish History." Journal of Modern Jewish Studies. 2010, 8(3): 319-335

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews" in Judith Baskin (ed.) Cambridge Dictionary of Judaism and Jewish Culture, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011. pp. 107.

- Weil, Shalva (2006). "Today is Purim: A Cochin Jewish Song in Hebrew". TAPASAM Journal: Quarterly Journal for Kerala Studies. 1 (3): 575–588.

Further reading

- Chiriyankandath, James (1 March 2008). "Nationalism, religion and community: A. B. Salem, the politics of identity and the disappearance of Cochin Jewry". Journal of Global History. 3 (1): 21–42. doi:10.1017/S1740022808002428.

- Katz, Nathan. (2000) Who Are the Jews of India?; Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21323-8

- Katz, Nathan; Goldberg, Ellen S; (1995) "Leaving Mother India: Reasons for the Cochin Jews' Migration to Israel", Population Review 39, 1 & 2 : 35–53.

- George Menachery, The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India, Vol. III, 2010, Plate f. p. 264 for 9 photographs, OCLC 1237836 ISBN 978-81-87132-06-6

- Paulose, Rachel. "Minnesota and the Jews of India", Asian American Press, 14 February 2012

- Weil, Shalva. "Obituary: Professor J. B. Segal." Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies. 2005, 7: 117-119.

- Weil, Shalva. "Indian Judaic Tradition." in Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby (eds) Religions in South Asia, London: Palgrave Publishers. 2006, pp. 169–183.

- Weil, Shalva. "Indo-Judaic Studies in the Twenty-First Century: A Perspective from the Margin", Katz, N., Chakravarti, R., Sinha, B. M. and Weil, S. (eds) New York and Basingstoke, England: Palgrave-Macmillan Press. 2007.

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews(South Asia)." in Paul Hockings (ed.) Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Boston, Mass: G.K. Hall & Co.2. 1992, 71-73.

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews." Encyclopaedia Judaica, Jerusalem, CDRom.1999.

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews." in Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember and Ian Skoggard (eds) Encyclopedia of World Cultures Supplement. New York: Macmillan Reference USA. 2002, pp. 78–80.

- Weil, Shalva. "Judaism-South Asia", in David Levinson and Karen Christensen (eds) Encyclopedia of Modern Asia. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 2004, 3: 284-286.

- Weil, Shalva. "Cochin Jews". in Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik (eds) Encyclopedia Judaica, 1st ed., Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, CD-Rom. 2007, (3: 335-339).

- Weil, Shalva. "Jews in India." in M.Avrum Erlich (ed.) Encyclopaedia of the Jewish Diaspora, Santa Barbara, USA: ABC CLIO. 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cochin Jews. |

- Cochin Jews

- (1687) Mosseh Pereyra de Paiva - Notisias dos Judeos de Cochim

- "Calcutta Jews", Jewish Encyclopedia, 1901-1906 edition

- "Cochin Jewish musical heritage", The Hindu, 15 May 2005

- news "Indian officials recount Cochin Jewish history", The Hindu, 11 September 2003

- The Synagogues of Kerala

- Synagogues of Chendamangalam and Pavur, Kerala