Jew (word)

The English term Jew originates in the Biblical Hebrew word Yehudi, meaning "from the Kingdom of Judah", or, in a more religieus meaning: 'worshipper of one God' [jehudi is made up of the first three letters of the tetragrammaton and the extension 'i' means 'I']. See Jastrow Dictionary and the source he used: Megilla 13a:2 (Talmud). It passed into Greek as Ioudaios and Latin as Iudaeus, which evolved into the Old French giu after the letter "d" was dropped. A variety of related forms are found in early English from about the year 1000, including Iudea, Gyu, Giu, Iuu, Iuw, and Iew, which eventually developed into the modern word.

| Look up Jew in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Etymology

Obv: Double cornucopia.

Rev: Five lines of ancient Hebrew script; reading "Yehochanan Kohen Gadol, Chever Hayehudim" (Yehochanan the High Priest, Council of the Jews.

Yehudi in the Hebrew Bible

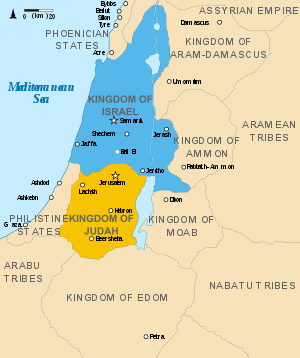

According to the Book of Genesis, Judah (יְהוּדָה, Yehudah) was the name of the fourth son of the patriarch Jacob. During the Exodus, the name was given to the Tribe of Judah, descended from the patriarch Judah. After the conquest and settlement of the land of Canaan, Judah also referred to the territory allocated to the tribe. After the splitting of the united Kingdom of Israel, the name was used for the southern kingdom of Judah. The kingdom now encompassed the tribes of Judah, Benjamin and Simeon, along with some of the cities of the Levites. With the destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel (Samaria), the kingdom of Judah became the sole Jewish state and the term y'hudi (יהודי) was applied to all Israelites.

The term Yehudi (יְהוּדִי) occurs 74 times in the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible. The plural, Yehudim (הַיְּהוּדִים) first appears in 2 Kings 16:6 where it refers to a defeat for the Yehudi army or nation, and in 2 Chronicles 32:18, where it refers to the language of the Yehudim (יְהוּדִית). Jeremiah 34:9 has the earliest singular usage of the word Yehudi. In Esther 2:5-6, the name "Yehudi" (יְהוּדִי) has a generic aspect, in this case referring to a man from the tribe of Benjamin:

- "There was a man a Yehudi (Jewish man) in Shushan the capital, whose name was Mordecai the son of Jair the son of Shimei the son of Kish, a Benjamite; who had been exiled from Jerusalem with the exile that was exiled with Jeconiah, king of Judah, which Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, had exiled."

The name appears in the Bible as a verb in Esther 8:17 which states:

- "Many of the people of the land became Yehudim (in the generic sense) (מִתְיַהֲדִים, mityahadim) because the fear of the Yehudim fell on them."

In some places in the Talmud the word Israel(ite) refers to somebody who is Jewish but does not necessarily practice Judaism as a religion: "An Israel(ite) even though he has sinned is still an Israel(ite)" (Tractate Sanhedrin 44a). More commonly the Talmud uses the term Bnei Yisrael, i.e. "Children of Israel", ("Israel" being the name of the third patriarch Jacob, father of the sons that would form the twelve tribes of Israel, which he was given and took after wrestling with an angel, see Genesis 32:28-29[1]) to refer to Jews. According to the Talmud then, there is no distinction between "religious Jews" and "secular Jews."

In modern Hebrew, the same word is still used to mean both Jews and Judeans ("of Judea"). In Arabic the terms are yahūdī (sg.), al-yahūd (pl.), and بَنُو اِسرَائِيل banū isrāʼīl. The Aramaic term is Y'hūdāi.

Development in European languages

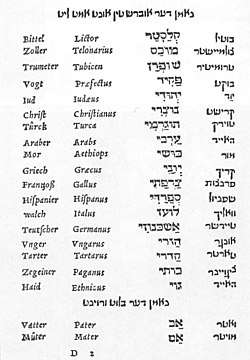

The Septuagint (reputedly a product of Hellenistic Jewish scholarship) and other Greek documents translated יְהוּדִי, Yehudi and the Aramaic Y'hūdāi using the Koine Greek term Ioudaios (Greek: Ἰουδαῖος; pl. Ἰουδαῖοι Ioudaioi), which had lost the 'h' sound. The Latin term, following the Greek version, is Iudaeus, and from these sources the term passed to other European languages. The Old French giu, earlier juieu, had elided (dropped) the letter "d" from the Latin Iudaeus. The Middle English word Jew derives from Old English where the word is attested as early as 1000 in various forms, such as Iudeas, Gyu, Giu, Iuu, Iuw, Iew. The Old English name is derived from Old French. The modern French term is "juif".

Most European languages have retained the letter "d" in the word for Jew. Etymological equivalents are in use in other languages, e.g., "Jude" in German, "judeu" in Portuguese, "jøde" in Danish and Norwegian, "judío" in Spanish, "jood" in Dutch, etc. In some languages, derivations of the word "Hebrew" are also in use to describe a Jew, e.g., Ebreo in Italian and Spanish, Ebri/Ebrani (Persian: عبری/عبرانی) in Persian and Еврей, Yevrey in Russian.[2] (See Jewish ethnonyms for a full overview.)

The German word "Jude" is pronounced [ˈjuːdə], the corresponding adjective "jüdisch" [ˈjyːdɪʃ] (Jewish), and is cognate with the Yiddish word for "Jew", "Yid".[3]

Modern use

In modern English, the term "Israelite" was used to refer to contemporary Jews as well as to Jews of antiquity until the mid-20th-century. Since the foundation of the State of Israel, it has become less common to use "Israelite" of Jews in general. Instead, citizens of the state of Israel, whether Jewish or not, are called "Israeli", while "Jew" is used as an ethno-religious designation.

Perception of offensiveness

The word Jew has been used often enough in a disparaging manner by antisemites that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was frequently avoided altogether, and the term Hebrew was substituted instead (e.g. Young Men's Hebrew Association). The word has become more often used in a neutral fashion, as it underwent a process known as reappropriation.[4][5] Even today some people are wary of its use, and prefer to use "Jewish". Indeed, when used as an adjective (e.g. "Jew lawyer") or verb (e.g. "to jew someone"),[6] the term Jew is purely pejorative. According to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition (2000):

It is widely recognized that the attributive use of the noun Jew, in phrases such as Jew lawyer or Jew ethics, is both vulgar and highly offensive. In such contexts Jewish is the only acceptable possibility. Some people, however, have become so wary of this construction that they have extended the stigma to any use of Jew as a noun, a practice that carries risks of its own. In a sentence such as There are now several Jews on the council, which is unobjectionable, the substitution of a circumlocution like Jewish people or persons of Jewish background may in itself cause offense for seeming to imply that Jew has a negative connotation when used as a noun.[7]

See also "Person of Jewish ethnicity" about a similar issue in the Soviet Union and modern Russia.

The word Jew has been subject to a 2017 monograph by scholar Cynthia Baker.[8]

See also

- Jewish ethnonym in various languages

- Ioudaioi, Greek

References

- http://bible.ort.org/books/pentd2.asp?ACTION=displaypage&BOOK=1&CHAPTER=32

- Falk, Avner (1996). A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews. Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-8386-3660-8.

- "Yiddish". Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (11th ed.). Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster. 2004. p. 1453. ISBN 0-87779-809-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stephen Paul Miller; Daniel Morris (2010). Radical Poetics and Secular Jewish Culture. University of Alabama Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8173-5563-0.

- M. Lynn Weiss (1998). Gertrude Stein and Richard Wright: The Poetics and Politics of Modernism. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-60473-188-0.

- "Notes". The Nation. New York: E. L. Godkin & Co. 14 (348): 137. February 29, 1872. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- Kleinedler, Steven; Spitz, Susan; et al., eds. (2005). The American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style. Houghton Mifflin Company. Jew. ISBN 978-0-618-60499-9.

- Boyarin, Jonathan (November 2018). "Cynthia Baker. Jew. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017. 190 pp". AJS Review. 42 (2): 441–443. doi:10.1017/S036400941800051X. ISSN 0364-0094.