Internment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges[1] or intent to file charges.[2] The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects".[3] Thus, while it can simply mean imprisonment, it tends to refer to preventive confinement rather than confinement after having been convicted of some crime. Use of these terms is subject to debate and political sensitivities.[4] Internment is also occasionally used to describe a neutral country's practice of detaining belligerent armed forces and equipment on its territory during times of war, under the Hague Convention of 1907.[5]

Interned persons may be held in prisons or in facilities known as internment camps, also known as concentration camps. The term concentration camp originates from the Spanish-Cuban Ten Years' War when Spanish forces detained Cuban civilians in camps in order to more easily combat guerrilla forces. Imperialist powers over the following decades continued to use concentration camps (the British during the Second Boer War and the Americans during the Philippine–American War).

This article involves internment generally, as distinct from the subset, the extermination camps, commonly referred to as death camps. The label concentration camp is often additionally used for the latter, such as those created by German forces during the Herero and Namaqua genocide, Italian forces during the Italian colonization of Libya, Nazi concentration camps during World War II, and Soviet gulags in operation into the 1980s.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights restricts the use of internment, with Article 9 stating, "No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile."[6]

Defining internment and concentration camp

The American Heritage Dictionary defines the term concentration camp as: "A camp where persons are confined, usually without hearings and typically under harsh conditions, often as a result of their membership in a group which the government has identified as dangerous or undesirable."[7]

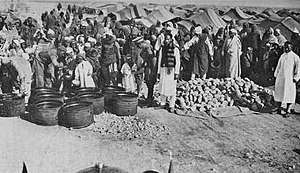

Although the first example of civilian internment may date as far back as the 1830s,[8] the English term concentration camp was first used in order to refer to the reconcentrados (reconcentration camps) which were set up by the Spanish military in Cuba during the Ten Years' War (1868–78).[9][10] The label was applied yet again to camps set up by the United States during the Philippine–American War (1899–1902).[11] And expanded usage of the concentration camp label continued, when the British set up camps during the Second Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa for interning Boers during the same time period.[9][12]

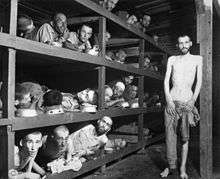

During the 20th century, the arbitrary internment of civilians by the state reached its most extreme forms in the Soviet Gulag system of concentration camps (1918–1991)[13] and the Nazi concentration camps (1933–45). The Soviet system was the first applied by a government on its own citizens.[10] The Gulag consisted in over 30,000 camps for most of its existence (1918–1991) and detained some 18 million from 1929 until 1953,[13] which is only a third of its 73-year lifespan. The Nazi concentration camp system was extensive, with as many as 15,000 camps[14] and at least 715,000 simultaneous internees.[15] The total number of casualties in these camps is difficult to determine, but the deliberate policy of extermination through labor in many of the camps was designed to ensure that the inmates would die of starvation, untreated disease and summary executions within set periods of time.[16] Moreover, Nazi Germany established six extermination camps, specifically designed to kill millions of people, primarily by gassing.[17][18]

As a result, the term "concentration camp" is sometimes conflated with the concept of an "extermination camp" and historians debate whether the term "concentration camp" or the term "internment camp" should be used to describe other examples of civilian internment.[4]

The former label continues to see expanded use for cases post-World War II, for instance in relation to British camps in Kenya during the Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960) for holding and torturing Kenyans,[19][20] and camps set up in Chile during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973–1990).[21] Today, some media reports have claimed that as many as 3 million Uyghurs and members of other Muslim minority groups are being held in China's re-education camps which are located in the Xinjiang region and which American news reports often label as concentration camps.[22][23] The camps were established under General Secretary Xi Jinping’s administration.[24][25]

Examples

- US Civil War (1861–1865)

- Boer War in South Africa (1900–1902)

- Concentration of Armenians during the Armenian Genocide (1915–1916)

- German concentration camps before and during World War II (1933–1945)

- Japanese internment of Europeans during World War II (−1945)

- Japanese-American internment camps in World War II (1942–1946)

- Japanese Canadian internment (1942–1949)

- Cyprus internment camps (1946–1949)

- Malayan New villages as part of the Briggs' Plan during the Malayan Emergency (1950–1960)

- Operation Demetrius in Northern Ireland (1971)

- Omarska camp in Bosnia, 1992

- Camp Bucca in Iraq (2003–2009)[26][27][28]

- Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq (1980–2014)[29][30][31]

- North Korean prison camps (1948–present)[32][33]

- Guantanamo Bay detention camp (2002–present)[34][35]

- Refugee detention centres in Libya (2011–present)[36][37][38][39][40]

- Uyghur re-education camps in China (2014–present)[41][42]

- Anti-gay detention camps in Chechnya (2017–present)[43][44][45][46]

- Trump administration migrant detentions as part of immigration detention in the United States (2018–present)[47][48][49][50]

See also

- Civilian internee

- Extermination through labor

- Extrajudicial detention

- Gulag

- House arrest

- Labor camp

- Kwalliso (North Korea's political penal labour colonies)

- Laogai (Chinese, "reform through labor")

- Military Units to Aid Production

- "Polish death camp" controversy

- Prison overcrowding

- Prisoner-of-war camp

- Prisons in North Korea

- Quasi-criminal

- Re-education camp (Vietnam)

- Re-education through labor

- Remand (detention)

References

- Lowry, David (1976). "Human Rights Vol. 5, No. 3 "INTERNMENT: DENTENTION WITHOUT TRIAL IN NORTHERN IRELAND"". Human Rights. American Bar Association: ABA Publishing. 5 (3): 261–331. JSTOR 27879033.

The essence of internment lies in incarceration without charge or trial.

- Kenney, Padraic (2017). Dance in Chains: Political Imprisonment in the Modern World. Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780199375745.

A formal arrest usually comes with a charge, but many regimes employed internment (that is, detention without intent to file charges)

- "the definition of internment". www.dictionary.com.

- "Euphemisms, Concentration Camps And The Japanese Internment". npr.org.

- "The Second Hague Convention, 1907". Yale.edu. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 9, United Nations

- "Concentration camp". American Heritage Dictionary. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- James L. Dickerson (2010). Inside America's Concentration Camps: Two Centuries of Internment and Torture. p. 29. Chicago Review Press ISBN 9781556528064

- "Concentration Camp". The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). Columbia University Press. 2008.

- "Concentration Camps Existed Long Before Auschwitz". Smithsonian. 2 November 2017.

- Storey, Moorfield; Codman, Julian (1902). Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root. Boston: George H. Ellis Company. pp. 89–95.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Documents re camps in Boer War". sul.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007.

- "Gulag: A History, by Anne Applebaum (Doubleday)". The Pulitzer Prizes. 2004. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- Concentration Camp Listing Sourced from Van Eck, Ludo Le livre des Camps. Belgium: Editions Kritak; and Gilbert, Martin Atlas of the Holocaust. New York: William Morrow 1993 ISBN 0-688-12364-3. In this online site are the names of 149 camps and 814 subcamps, organized by country.

- Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3.

- Marek Przybyszewski, IBH Opracowania – Działdowo jako centrum administracyjne ziemi sasińskiej (Działdowo as the centre of local administration). Internet Archive, 22 October 2010.

- Robert Gellately; Nathan Stoltzfus (2001). Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany. Princeton University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-691-08684-2.

- Anne Applebaum, A History of Horror, Review of "Le Siècle des camps" by Joël Kotek and Pierre Rigoulot, The New York Review of Books, 18 October 2001

- "Museum of British Colonialism releases online 3D models of British concentration camps in Kenya". Morning Star. 27 August 2019.

- "The Mau Mau Rebellion". The Washington Post. 31 December 1989.

- "Chilean coup: 40 years ago I watched Pinochet crush a democratic dream". The Guardian. 7 September 2013.

- "As the U.S. Targets China's 'Concentration Camps,' Xinjiang's Human Rights Crisis is Only Getting Worse". Newsweek. 22 May 2019.

- "Uighurs and their supporters decry Chinese 'concentration camps,' 'genocide' after Xinjiang documents leaked". Washington Post. 17 November 2019.

- Ramzy, Austin; Buckley, Chris (16 November 2019). "'Absolutely No Mercy': Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Kate O’Keeffe and Katy Stech Ferek (14 November 2019). "Stop Calling China's Xi Jinping 'President,' U.S. Panel Says". The Wall Street Journal.

- "Open Letter to Members of the Security Counsel Concerning Detentions in Iraq" (PDF).

- "Largest American Internment Camp in Iraq Shuts Down | The Takeaway". WNYC Studios. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "How U.S. Torture Led to the Rise of ISIS". The Big Picture. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Excerpts From Red Cross Report". Wall Street Journal. 7 May 2004. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Anderson, Jon Lee (26 July 2013). "Breaking Out of Abu Ghraib". ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Defense.gov News Article: Abuse Resulted From Leadership Failure, Taguba Tells Senators". archive.defense.gov. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Life inside a North Korea labour camp: 'We were forced to throw rocks at a man being hanged'". The Independent. 28 September 2017.

- "Political Prison Camps in North Korea Today" (PDF). 19 October 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Leigh, David (25 April 2011). "Guantánamo Bay files: Torture gets results, US military insists". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "Professor David Isaacs Speech" (PDF).

- EXCLUSIVE: Italian doctor laments Libya's 'concentration camps' for migrants, retrieved 18 December 2019

- "Europe's apathy toward humanitarian rescue outrages NGOs". InfoMigrants. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Wehrey, Frederic (25 November 2019). "What the 'Danish Lawrence' Learned in Libya (5th paragraph from the last one)". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "Detained migrants killed in Libya airstrike used as 'human shields'".

- Mediapart, La Rédaction De. "France cancels speedboats delivery to Libyan coastguard". Mediapart. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "China is creating concentration camps in Xinjiang. Here's how we hold it accountable". The Washington Post. 24 November 2018.

- "Saudi crown prince defends China's right to put Uighur Muslims in concentration camps". The Daily Telegraph. 22 February 2019.

- "The persecution of gay men in Chechnya has chilling similarities to the Third Reich". NewsComAu. 19 April 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Stefanello, Viola (15 January 2019). "Is there a 'gay purge' in Chechnya? Rights group fears the worst". euronews. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Report: Chechnya Opens 'Concentration Camp for Homosexuals'". Snopes.com. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Question to the EU Commission by Matt Carthy" (PDF).

- Hignett, Katherine (24 June 2019). "Academics rally behind Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez over concentration camp comments: 'She is completely historically accurate'". Newsweek. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Holmes, Jack (13 June 2019). "An Expert on Concentration Camps Says That's Exactly What the U.S. Is Running at the Border". Esquire. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Beorn, Waitman Wade (20 June 2018). "Yes, you can call the border centers 'concentration camps,' but apply the history with care". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Adams, Michael Henry. "Learning from the Germans: How We Might Atone for America's Evils". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

Cages detaining refugees at the southern border are indeed 'concentration camps'.

Further reading

- Stone, Dan (2017). Concentration Camps: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198790709.

- Smith, Iain R.; Stucki, Andreas (September 2011). "The Colonial Development of Concentration Camps (1868–1902)". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 39 (3): 417–437. doi:10.1080/03086534.2011.598746.

External links