Bukharan Jews

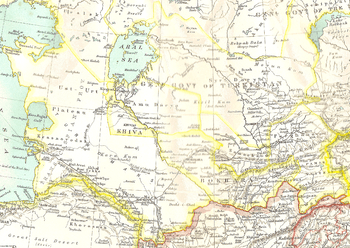

Bukharan Jews, also Bukharian Jews or Bukhari Jews (Russian: Бухарские евреи Bukharskie evrei; Hebrew: בוכרים Bukharim; Tajik and Bukhori Cyrillic: яҳудиёни бухороӣ Yahudiyoii bukhoroī (Bukharan Jews) or яҳудиёни Бухоро Yahudiyoni Bukhoro (Jews of Bukhara), Bukhori Hebrew Script: יהודיי בוכאראי and יהודי בוכארי, Uzbek بوُخارا يههوديلهری[2] bukhara yähudiläri), are a Jewish ethno-religious group of Central Asia which historically spoke Bukhori, a Tajik dialect of the Persian language. Their name comes from the former Central Asian Emirate of Bukhara, which once had a sizable Jewish community. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the great majority have immigrated to Israel or to the United States (especially Forest Hills, New York), while others have immigrated to Europe or Australia.[4]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 180,000–250,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 100,000–120,000 | |

| 70,000 50,000[1] | |

| 5,000–10,000 | |

| 1,500 150[1][2] | |

| 1,500 | |

| 1,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Traditionally Bukhori (Tajik Persian), Tajik, Russian, Hebrew (Israel), English (USA, Canada, UK and Australia) and German (Austria and Germany) spoken in addition and to a lesser extent, Uzbek[3] for those who remain in Uzbekistan | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism, Islam (see Chala), Christianity (among those who migrated to Russia or the United States) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Jewish groups (Mizrahi, Sephardi, Ashkenazi, Bene-Israeli, etc.) and Tadjiks | |

Name and language

The term Bukharan was coined by European travelers who visited Central Asia around the 16th century. Since most of the Jewish community at the time lived under the Emirate of Bukhara, they came to be known as Bukharan Jews. The name by which the community called itself is "Isro'il" (Israelites).

The appellative Bukharian was adopted by Bukharan Jews who moved to English-speaking countries, in an anglicisation of the Hebrew Bukhari. However, Bukharan was the term used historically by English writers, as it was for other aspects of Bukhara.

Bukharan Jews used the Persian language to communicate among themselves and later developed Bukhori, a Tajik dialect of the Persian language with small linguistic traces of Hebrew. This language provided easier communication with their neighboring communities and was used for all cultural and educational life among the Jews. It was used widely until the area was "Russified" by the Russians and the dissemination of "religious" information was halted. The elderly Bukharan generation use Bukhori as their primary language but speak Russian with a slight Bukharan accent. The younger generation use Russian as their primary language, but do understand or speak Bukhori.

The Bukharan Jews are Mizrahi Jews[4] and have been introduced to and practice Sephardic Judaism.

The first primary written account of Jews in Central Asia dates to the beginning of the 4th century CE. It is recalled in the Talmud by Rabbi Shmuel bar Bisna, a member of the Talmudic academy in Pumbeditha, who traveled to Margiana (present-day Merv in Turkmenistan) and feared that the wine and alcohol produced by local Jews was not kosher.[5] The presence of Jewish communities in Merv is also proven by Jewish writings on ossuaries from the 5th and 6th centuries, uncovered between 1954 and 1956.[6]

History

According to some ancient texts, there were Israelites that began traveling to Central Asia to work as traders during the reign of King David of Jerusalem as far back as the 10th century B.C.E.[7] When Persian King Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon in 539 BC, he encouraged the Jews he liberated to settle in his empire, which included areas of Central Asia. In the Middle Ages, the largest Jewish settlement in Central Asia was in the Emirate of Bukhara.

Among Bukharan Jews, there are two ancient theories of how Jewish people settled in Central Asia. One theory is that Bukharan Jews may be descended from the Tribe of Naphtali and the Tribe of Issachar of the Ten Lost Tribes[8] who may have been exiled during the Assyrian captivity of Israel in the 7th century BCE.[9] Isakharov (in different spellings) is a common surname.[10]

Modern sources have described the Bukhara Jews as, for example, "an ethnic and linguistic group in Central Asia, claiming descent from 5th-century exiles from Persia".[11]

The Bukharan Jews are considered one of the oldest ethno-religious groups of Central Asia and over the years they have developed their own distinct culture. Throughout the years, Jews from other Eastern countries such as Iraq, Iran, Yemen, Syria, and Morocco migrated into Central Asia (usually by taking the Silk Road).

16th to 18th centuries

Around 1620, the first synagogue was constructed at Bukhara city. This was done in contravention of the law prescribed to Caliph Omar who forbade the construction of new non-Muslim places of worship including synagogues as well as forbade the destruction of those that existed in the pre-Islamic period. There was a case when Caliph Umar had ordered the destruction of a mosque, which was built illegally on Jewish land.[12][13][14] Before the construction of the first synagogue, Jews had shared a place in a mosque with Muslims. This mosque was called the Magoki Attoron (the "Mosque in pit"). Some say that Jews and Muslims worshipped alongside each other in the same place at the same time. Other sources insist that Jews worshipped after Muslims.[15] The construction of the first Bukhara synagogue was credited to two people: Nodir Divan-Begi, an important grandee, and an anonymous widow, who reportedly outwitted an official.

During the 18th century, Bukharan Jews faced considerable discrimination and persecution. Jewish centers were closed down, the Muslims of the region usually forced conversion on the Jews, and the Bukharan Jewish population dramatically decreased to the point where they were almost extinct.[16] Due to pressures to convert to Islam, persecution, and isolation from the rest of the Jewish world, the Jews of Bukhara began to lack knowledge and practice of their Jewish religion. By the middle of the 18th century, practically all Bukharan Jews lived in the Bukharan Emirate.

Rabbi Yosef Maimon

In 1793, Rabbi Yosef Maimon, a Sephardic Jew from Tetuan, Morocco and prominent kabbalist in Safed, traveled to Bukhara and found the local Jews in a very bad state. He decided to settle there. Maimon was disappointed to see so many Jews lacking knowledge and observance of their religious customs and Jewish law. He became a spiritual leader, aiming to educate and revive the Jewish community's observance and faith in Judaism. He changed their Persian religious tradition to Sephardic Jewish tradition. Maimon is an ancestor of Shlomo Moussaieff, author Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, and the former First Lady of Iceland Dorrit Moussaieff.

19th century

In 1843 the Bukharan Jews were visited by the so-called "Eccentric Missionary", Joseph Wolff, a Jewish convert to Christianity who had set himself the broad task of finding the Lost Tribes of Israel and the narrow one of seeking two British officers who had been captured by the Emir, Nasrullah Khan. Wolff wrote prolifically of his travels, and the journals of his expeditions provide valuable information about the life and customs of the peoples he travelled amongst, including the Bukharan Jews. In 1843, for example, they collected 10,000 silver tan'ga and purchased land in Samarkand, known as Makhallai Yakhudion, close to Registon.

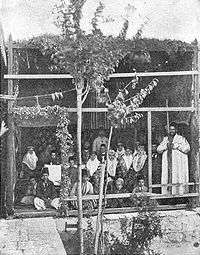

In the middle of the 19th century, Bukharan Jews began to move to Palestine. The land on which they settled in Jerusalem was named the Bukharim quarter (Sh'hunat HaBucharim) and still exists today.

In 1865, Russian troops took over Tashkent, and there was a large influx of Jews to the newly created Turkestan Region. From 1876 to 1916, Jews were free to practice Judaism. Dozens of Bukharan Jews held prestigious jobs in medicine, law, and government, and many Jews prospered. Many Bukharan Jews became successful and well-respected actors, artists, dancers, musicians, singers, film producers, and sportsmen. Several Bukharan entertainers became artists of merit and gained the title "People's Artist of Uzbekistan", "People's Artist of Tajikistan", and even (in the Soviet era) "People's Artist of the Soviet Union". Jews succeeded in the world of sport also, with several Bukharan Jews in Uzbekistan becoming renowned boxers and winning many medals for the country.[17] Still, Bukharan Jews were forbidden to ride in the streets and had to wear distinctive costumes. They were relegated to a ghetto, and often fell victim to persecution from the Muslim majority.[18]

Soviet era

_-_FOUR_GENERATIONS_OF_THE_KALANTAROV_FAMILY_LIGHT_THE_HANNUKAH_CANDLES.jpg)

By the time of the Russian revolution, the Bukharan Jews were one of the most isolated Jewish communities in the world.[19]

In Central Asia, the community attempted to preserve their traditions while displaying loyalty to the government. World War II and the Holocaust brought a lot of Ashkenazi Jewish refugees from the European regions of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe through Uzbekistan.

Starting in 1972, one of the largest Bukharan Jewish emigrations in history occurred as the Jews of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan immigrated to Israel and the United States, due to looser restrictions on immigration. In the late 1980s to the early 1990s, almost all of the remaining Bukharan Jews left Central Asia for the United States, Israel, Europe, or Australia in the last mass emigration of Bukharan Jews from their resident lands.

_(2).jpg)

After 1991

With the disintegration of the Soviet Union and foundation of the independent Republic of Uzbekistan in 1991, some feared growth of nationalistic policies in the country. The resurgence of Islamic fundamentalism in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan prompted an increase in the level of emigration of Jews (both Bukharan and Ashkenazi). Before the collapse of the USSR, there were 45,000 Bukharan Jews in Central Asia.[20]

Today, there are about 150,000 Bukharan Jews in Israel (mainly in the Tel Aviv metropolitan area including the neighborhoods of Tel Kabir, Shapira, Kiryat Shalom, HaTikvah and cities like Or Yehuda, Ramla, and Holon) and 60,000 in the United States (especially Queens—a borough of New York that is widely known as the "melting pot" of the United States due to its ethnic diversity)—with smaller communities in the USA like Phoenix, South Florida, Atlanta, San Diego, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Denver. Only a few thousand still remain in Uzbekistan. About 500 live in Canada (mainly Toronto, Ontario and Montreal, Quebec). Almost no Bukharan Jews remain in Tajikistan (compared to the 1989 Jewish population of 15,000 in Tajikistan).

Immigrant populations

Tajikistan

In early 2006, the still-active Dushanbe Synagogue in Tajikistan as well as the city's mikveh (ritual bath), kosher butcher, and Jewish schools were demolished by the government (without compensation to the community) to make room for the new Palace of Nations. After an international outcry, the government of Tajikistan announced a reversal of its decision and publicly claimed that it would permit the synagogue to be rebuilt on its current site. However, in mid-2008, the government of Tajikistan destroyed the whole synagogue and started construction of the Palace of Nations. The Dushanbe synagogue was Tajkistan's only synagogue and the community were therefore left without a centre or a place to pray. As a result, the majority of Bukharan Jews from Tajikistan living in Israel and the United States have very negative views towards the Tajik government and many have cut off all ties they had with the country. In 2009, the Tajik government reestablished the synagogue in a different location for the small Jewish community.[21]

United States

_01_-_Congregation_Beth-El.jpg)

Currently, Bukharan Jews are mostly concentrated in the U.S. in New York City.[4] New York City's 108th Street in the borough of Queens, often referred to as "Bukharan Broadway"[22] or "Bukharian Broadway"[19] in Forest Hills, Queens, is filled with Bukharan restaurants and gift shops. Furthermore, Forest Hills is nicknamed "Bukharlem" due to the majority of the population being Bukharian.[23] They have formed a tight-knit enclave in this area that was once primarily inhabited by Ashkenazi Jews (many of the Ashkenazi Jews have assimilated to wider American and American Jewish culture with each successive generation). Congregation Tifereth Israel in Corona, Queens, a synagogue founded in the early 1900s by Ashkenazi Jews, became Bukharan in the 1990s. Kew Gardens, Queens, also has a very large population of Bukharan Jews. Author Janet Malcolm has taken an interest in Bukharan Jews in the U.S., writing at length about Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson and, in Iphigenia in Forest Hills: Anatomy of a Murder Trial, about the 2007 contract murder of Daniel Malakov organized by his ex-wife Mazoltuv Borukhova. Although Bukharian Jews in Queens remain insular in some ways (living in close proximity to each other, owning and patronizing clusters of stores, and attending their own synagogue rather than other synagogues in the area), they have connections with non-Bukharians in the area. Their children, for example, usually attend local public schools do things other American children do.

In December 1999, the First Congress of the Bukharian Jews of the United States and Canada convened in Queens.[24] In 2007, Bukharan-American Jews initiated lobbying efforts on behalf of their community.[25] Zoya Maksumova, president of the Bukharan women's organization "Esther Hamalka" said "This event represents a huge leap forward for our community. Now, for the first time, Americans will know who we are." Senator Joseph Lieberman intoned, "God said to Abraham, 'You'll be an eternal people'… and now we see that the State of Israel lives, and this historic [Bukharan] community, which was cut off from the Jewish world for centuries in Central Asia and suffered oppression during the Soviet Union, is alive and well in America. God has kept his promise to the Jewish people."[25]

Culture

Dress codes

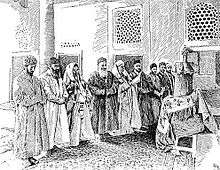

Bukharan Jews had their own dress code, similar to but also different from other cultures (mainly Turco-Mongol) living in Central Asia. On weddings today, one can still observe the bride and the close relatives donning the traditional kaftan (Jomah-ҷома-ג'אמה in Bukhori and Tajik).[26]

Music

The Bukharan Jews have a distinct musical tradition called Shashmaqam, which is an ensemble of stringed instruments, infused with Central Asian rhythms, and a considerable klezmer influence as well as Muslim melodies, and even Spanish chords. The main Instrument is called Dayereh. Shashmaqam music "reflect the mix of Hassidic vocals, Indian and Islamic instrumentals and Sufi-inspired texts and lyrical melodies."[27] Ensemble Shashmaqam was one of the first New York based Ensembles created to showcase the music and dance of Bukharan Jews. The Ensemble was created in 1983 by Shumiel Kuyenov, a Dayereh player from Queens.

Cuisine

Bukharan cuisine consists of many unique dishes, distinctly influenced by ethnic dishes historically and currently found along the Silk Road and many parts of Central and even Southeast Asia. Shish kabob, or shashlik, as it is often referred to in Russian, are popular, made of chicken, beef or lamb. Pulled noodles, often thrown into a hearty stew of meat and vegetables known as lagman, are similar in style to Chinese lamian, also traditionally served in a meat broth. Samsa, pastries filled with spiced meat or vegetables, are baked in a unique, hollowed out tandoor oven, and greatly resemble the preparation and shape of Indian samosas.

The Bukharians' Jewish identity was always preserved in the kitchen. "Even though we were in exile from Jerusalem, we observed kashruth," said Isak Masturov, another owner of Cheburechnaya. "We could not go to restaurants, so we had to learn to cook for our own community.[28]

Plov is a very popular slow-cooked rice dish spiced with cumin and containing carrots, and in some varieties, chick peas or raisins, and often topped with beef or lamb. Another popular dish is baksh which consists of rice, beef and liver cut into small cubes, with cilantro, which adds a shade of green to the rice once it's been cooked. Most Bukharan Jewish communities still produce their traditional breads including non (lepyoshka in Russian), a circular bread with a flat center that has multiple pattern of designs, topped with black and regular sesame seeds, and the other, called non toki, bears the dry and crusty features of traditional Jewish matzah, but with a distinctly wheatier taste.

After Sabbath synagogue service, Bukharin Jews often eat steamed eggs and sweet potatoes followed by a dish of fish such as carp. Next comes the main meal called oshesvo.

U.K.

Yvonne Green (née Mammon) Award Winning Poet & Semyon Izrailevich Lipkin’s translator, published by Smith/Doorstop.

Israel

- Yisrael Aharoni – Israeli chef and restaurateur

- Yoni Ben-Menachem – Israeli journalist; General Director of Israel Broadcasting Authority

- Amnon Cohen – Israeli politician and member of the Knesset for Shas

- Guy Haimov – professional football player

- Shimon Hakham – Bukharan-Israeli rabbi, writer, one of the founders of the Bukharan Quarter

- Robert Ilatov – Israeli politician and member of the Knesset for Yisrael Beiteinu

- Avi Issacharoff – Israeli journalist and creator of the series Fauda

- Lev Leviev – billionaire businessman, investor, philanthropist, president of the World Congress of Bukharian Jews

- Nitzan Kaikov – Israeli songwriter and music producer

- Yosef Maimon – religious leader

- Rinat Matatov – Israeli actress

- Moshe Mishaelof – professional football player

- Shlomo Moussaieff – co-founder of the Bukharan Quarter in Jerusalem

- Shlomo Moussaieff – Israeli millionaire businessman

- Dorrit Moussaieff – former First Lady of Iceland

- Rafael Pinhasi – Israeli politician and member of the Knesset for Shas

- Esther Roth-Shahamorov – Israeli former track and field athlete

- Gideon Sa'ar – Israeli politician who served as a member of Knesset for Likud

- Yulia Shamalov-Berkovich – Israeli politician who currently serves as a member of the Knesset for Kadima

- Idan Yaniv – Israeli singer, "2007 Israeli Artist of the Year"

- Benjamin Yusupov – Israeli classical composer, conductor and pianist

United States

- Jacob Arabov – proprietor of Jacob & Co.

- Boris Kandov – President of the Bukharian Jewish Congress of the US and Canada

- Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson – author

- Jacob Nasirov – Bukharan-American rabbi from Afghanistan (member of the Bukharian Rabbinical Counsel)

- Rus Yusupov – Bukharan-American Internet entrepreneur; co-founder of Vine

- Iosef Yusupov – designer

- Michael Aronov - American actor and playwright, Tony Award winner

Other

- Ari Babakhanov – musician from Uzbekistan

- Rena Galibova – Soviet actress, "People's Artist of Tajikistan" (an awarded title, alluding to national prominence)

- Meirkhaim Gavrielov – journalist murdered in Tajikistan in 1998

- Barno Itzhakova – vocalist, famous for her rendition of traditional Shashmaqom songs in Tajik and Uzbek

- Malika Kalontarova – dancer, "People's Artist of Soviet Union" (Queen of Eastern Dance)

- Fatima Kuinova – Soviet singer, "Merited Artist of the Soviet Union"

- Ilyas Malayev – musician and poet from Uzbekistan, "Honoured Artist of Uzbekistan"

- Shoista Mullodzhanova – Shashmakon singer, "People's Artist of Tajikistan" (Queen of Shashmakom music)

- Gavriel Mullokandov – popular Shashmakom artist, "People's Artist of Uzbekistan"

- Anthony Yadgaroff – British businessman, Jewish community leader

- Suleiman Yudakov – Soviet composer and musician, "People's Artist of the Uzbek SSR"

See also

- Bukharan Jews in Israel

- Africa Israel Investments

- Bais Yaakov Machon Academy

- Dushanbe Synagogue

- Emirate of Bukhara

- History of the Jews in Russia and the Soviet Union

- History of the Jews under Muslim Rule

- Ohr Avner Foundation

- Bukhori dialect

References

Notes

- "In Bukhara, 10,000 Jewish Graves but Just 150 Jews". New York Times. 7 April 2018.

- Ido, Shinji (June 15, 2017). "The Vowel System of Jewish Bukharan Tajik: With Special Reference to the Tajik Vowel Chain Shift". Journal of Jewish Languages. 5 (1): 81–103. doi:10.1163/22134638-12340078. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Ido, Shinji (2016). "A late 19th-century Uzbek text in Hebrew script" (PDF). Turkic Languages. 20 (2): 216–233. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Goodman, Peter. "Bukharian Jews find homes on Long Island", Newsday, September 2004.

- Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Aboda Zara, 31b, and Rashi

- Ochildiev, D; R. Pinkhasov, I. Kalontarov. A History and Culture of the Bukharian Jews, Roshnoyi-Light, New York, 2007.

- Abazov, Rafis (2007). Culture and Customs of the Central Asian Republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 75. ISBN 9780313336560. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- Ehrlich, M. Avrum. Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture ABL-CIO, October 2008, ISBN 978-1-85109-873-6, p. 84.

- "The history of Bukharan Jews", Bukharacity.com. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- "Isakharov Surname Meaning, Origins & Distribution". forebears.co.uk. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "Wandering Jew: Bukhara, the ancient silk way city", by Tanya Powell-Jones, Jerusalem Post, 1/13/2013

- "Lyab-i Khauz ensemble, Magoki Attoron Mosque and the story of Synagogue in Bukhara". Pagetour.narod.ru. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- Thomas, David; Roggema, Barbara (30 November 2009). Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History (600–900). BRILL. p. 360. ISBN 978-90-04-16975-3. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- Abu-Munshar, Maher Y. (2007-09-15). Islamic Jerusalem and its Christians: a history of tolerance and tensions. Tauris Academic Studies. p. 63. ISBN 9781845113537.

- Mosque and the story of Synagogue in Bukhara. "Bukharan Jews", Magoki Attoron.

- "Bukharan Jews – History and Cultural Relations", everyculture.com website. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- Pinkhasov, Peter. "The History of Bukharian Jews", Bukharian Jewish Global Portal website, p. 2. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- "Afghanistan — Viewer — World Digital Library". www.wdl.org. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Moskin, Julia. "The Silk Road Leads to Queens" The New York Times, January 18, 2006.

- Cooper, Alanna E. (2003). "Looking Out for One's Own Identity: Central Asian Jews in the Wake of Communism". In Kosmin, Barry Alexander; Kovács, András (eds.). New Jewish Identities: Contemporary Europe and Beyond. Central European University Press. pp. 189–210. ISBN 963-9241-62-8.

- "New Synagogue Opens In Dushanbe". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "Bukharan Broadway":

- Foner, Nancy. New immigrants in New York", Columbia University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-231-12415-7, p. 133. "Since the 1970s, more than 35,000 "Bukharan" émigrés have created a bustling community in Forest Hills, with restaurants, barbershops, food stores and synagogue that together have given 108th street the nickname 'Bukharan Broadway'".

- Morel, Linda. "Bukharan Jews now in Queens recreate their Sukkot memories", j. (Jewish Telegraphic Agency), September 20, 2002. "... 108th Street, recently dubbed 'Bukharan Broadway,'..."

- Victor Wishna, "A Lost Tribe...Found in Queens" Archived August 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, San Diego Jewish Journal, October 2003. "Leaving the bakery, we walk along what has been dubbed 'Bukharan Broadway,' where an abundance of restaurants and gift shops sit side by side."

- Popik, Barry. "Buharlem or Bukharlem (Bukhara + Harlem)". www.barrypopik.com. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- "Heritage". bucharianlife.blogspot.com. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Ruby, Walter."The Bukharian Lobby" Archived February 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, The Jewish Week, October 31, 2007.

- For examples see men and women coats as well as children's clothing from Bukhara, ["Dress Codes: Revealing the Jewish Wardrobe" "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-03. Retrieved 2014-07-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)] exhibition, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, March 11, 2014 – October 18, 2014

- "Shashmaqam". The Wandering Muse. Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- NYT,1-18-2006 The Silk Road Leads to Queens

Bibliography

- Ricardo Garcia-Carcel: La Inquisición, Biblioteca El Sol. Biblioteca Básica de Historia. Grupo Anaya, Madrid, Spain 1990. ISBN 84-7969-011-9.

External links

- Joseph Mammon. My Story

- Official World Wide Bukharian Community Website

- BJews.com, Bukharian Jewish Global Portal

- Cooper, Alanna E. Bukharan Jews and the Dynamics of Global Judaism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

- "Alanna's Cooper's publications on Bukharan Jews", kikayon.com

- Elena Neva, "Heavenly Frogs in the Art of Bukharian Jewelers", Kunstpedia, March 19, 2009.

- "Bukharian Jews protect their culture in a N.Y. enclave", Haaretz (Reuters), October 21, 2009.

- LAZGI Firuza Jumaniyazova shimon polatov israel 2011 on YouTube

- AVRAM TOLMAS, RUSTAM, YASHA BARAEV on YouTube

- Malika Kalantarova - Lazgi.avi on YouTube

- Lazgi Malika Kalontarova Dushanbe Малика Калонтарова Лазги Душанбе on YouTube

- Bukharian Torah Lectures by Bukharian Rabbis