Population transfer

Population transfer or resettlement is the movement of a large group of people from one region to another, often a form of forced migration imposed by state policy or international authority and most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion but also due to economic development. Banishment or exile is a similar process, but is forcibly applied to individuals and groups.

Often the affected population is transferred by force to a distant region, perhaps not suited to their way of life, causing them substantial harm. In addition, the loss of all immovable property and, when rushed, the loss of substantial amounts of movable property, is implied. This transfer may be motivated by the more powerful party's desire to make other uses of the land in question or, less often, by disastrous environmental or economic conditions that require relocation.

The first known population transfers date back to Ancient Assyria in the 13th century BCE. The last major population transfer in Europe was the deportation of 800,000 ethnic Albanians, during the Kosovo war in 1999.[1] The single largest population transfer in history was the flight and expulsion of Germans after World War II, which involved more than 12 million people. Moreover, some of the largest population transfers in Europe have been attributed to the ethnic policies of the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. The best-known recent example caused by economic development is that resulting from the construction of the Three Gorges Dam in China.

Specific types of population transfer

Population exchange

Population exchange is the transfer of two populations in opposite directions at about the same time. In theory at least, the exchange is non-forcible, but the reality of the effects of these exchanges has always been unequal, and at least one half of the so-called "exchange" has usually been forced by the stronger or richer participant. Such exchanges have taken place several times in the 20th century:

- The traumatic partition of India and Pakistan

- The mass expulsion of Anatolian Greeks and Greek Muslims from Turkey and Greece, respectively, during their so-called Greek-Turkish population exchange. It involved approximately 1.3 million Anatolian Greeks and 354,000 Greek Muslims, most of whom were forcibly made refugees and de jure denaturalized from their homelands.

Ethnic dilution

This refers to the practice of enacting immigration policies to relocate parts of a ethnically and/or culturally dominant population into a region populated by an ethnic minority or otherwise culturally different or non-mainstream group, in order to dilute, and eventually transform the native ethnic population into the mainstream culture over time. An example is the Sinicization of Tibet.

Issues

According to the political scientist Norman Finkelstein, population transfer was considered as an acceptable solution to the problems of ethnic conflict until around World War II and even for a time afterward. Transfer was considered a drastic but "often necessary" means to end an ethnic conflict or ethnic civil war.[2] The feasibility of population transfer was hugely increased by the creation of railroad networks from the mid-19th century.

Population transfer differs more than simply technically from individually motivated migration, but at times of war, the act of fleeing from danger or famine often blurs the differences. If a state can preserve the fiction that migrations are the result of innumerable "personal" decisions, the state may be able to claim that it is not to blame for the expulsions. Jews who had signed over properties in Germany and Austria during Nazism, although coerced to do so, found it nearly impossible to be reimbursed after World War II, partly because of the ability of governments to make the "personal decision to leave" argument. George Orwell, in his 1946 essay "Politics and the English Language" (written during the World War II evacuation and expulsions in Europe), observed:

- "In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. Things... can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.... Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers."

Changes in international law

The view of international law on population transfer underwent considerable evolution during the 20th century. Prior to World War II, many major population transfers were the result of bilateral treaties and had the support of international bodies such as the League of Nations. The expulsion of Germans after World War II from Central and Eastern Europe after World War II was sanctioned by the Allies in Article 13 of the Potsdam communiqué, but research has shown that both the British and the American delegations at Potsdam strongly objected to the size of the population transfer that had already taken place and was accelerating in the summer of 1945. The principal drafter of the provision, Geoffrey Harrison, explained that the article was intended not to approve the expulsions but to find a way to transfer the competence to the Control Council in Berlin to regulate the flow.[3]

The tide started to turn when the Charter of the Nuremberg Trials of German Nazi leaders declared forced deportation of civilian populations to be both a war crime and a crime against humanity.[4] That opinion was progressively adopted and extended through the remainder of the century. Underlying the change was the trend to assign rights to individuals, thereby limiting the rights of states to make agreements that adversely affect them.

There is now little debate about the general legal status of involuntary population transfers: "Where population transfers used to be accepted as a means to settle ethnic conflict, today, forced population transfers are considered violations of international law."[5] No legal distinction is made between one-way and two-way transfers since the rights of each individual are regarded as independent of the experience of others.

Article 49 of Fourth Geneva Convention (adopted in 1949 and now part of customary international law) prohibits mass movement of people out of or into occupied territory under belligerent military occupation:[6]

Individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory to the territory of the Occupying Power or to that of any other country, occupied or not, are prohibited, regardless of their motive.... The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.

An interim report of the United Nations Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities (1993) says:[7]

Historical cases reflect a now-foregone belief that population transfer may serve as an option for resolving various types of conflict, within a country or between countries. The agreement of recognized States may provide one criterion for the authorization of the final terms of conflict resolution. However, the cardinal principle of "voluntariness" is seldom satisfied, regardless of the objective of the transfer. For the transfer to comply with human rights standards as developed, prospective transferees must have an option to remain in their homes if they prefer.

The same report warned of the difficulty of ensuring true voluntariness:

"some historical transfers did not call for forced or compulsory transfers, but included options for the affected populations. Nonetheless, the conditions attending the relevant treaties created strong moral, psychological and economic pressures to move."

The final report of the Sub-Commission (1997)[8] invoked numerous legal conventions and treaties to support the position that population transfers contravene international law unless they have the consent of both the moved population and the host population. Moreover, that consent must be given free of direct or indirect negative pressure.

"Deportation or forcible transfer of population" is defined as a crime against humanity by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Article 7).[9] The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia has indicted and sometimes convicted a number of politicians and military commanders indicted for forced deportations in that region.

Ethnic cleansing encompasses "deportation or forcible transfer of population" and the force involved may involve other crimes, including crimes against humanity. Nationalist agitation can harden public support, one way or the other, for or against population transfer as a solution to current or possible future ethnic conflict, and attitudes can be cultivated by supporters of either plan of action with its supportive propaganda used as a typical political tool by which their goals can be achieved.

Timothy V. Waters argues, in "On the Legal Construction of Ethnic Cleansing," that the expulsions of the ethnic German population east of the Oder-Neisse line the Sudetenland and elsewhere in Eastern Europe without legal redress has set a legal precedent that can permit future ethnic cleansing of other populations under international law.[10] His paper has, however, been rebutted by Jakob Cornides's study "The Sudeten German Question after EU Enlargement."[11]

In Europe

France

Two famous transfers connected with the history of France are the banning of the religion of the Jews in 1308 and that of the Huguenots, French Protestants by the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685. Religious warfare over the Protestants led to many seeking refuge in the Low Countries and in England. In the early 18th century, some Huguenots emigrated to colonial America. In both cases, the population was not forced out but rather their religion was declared illegal and so many left the country.

According to Ivan Sertima, Louis XV ordered all blacks to be deported from France but was unsuccessful. At the time, they were mostly free people of color from the Caribbean and Louisiana colonies, usually descendants of French colonial men and African women. Some fathers sent their mixed-race sons to France to be educated or gave them property to be settled there. Others entered the military, as did Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, the father of Alexandre Dumas.[12]

Ireland

_p_438_Map_of_Connaught%2C_as_laid_out_to_receive_the_Inhabitants_from_the_several_Counties_ofthe_other_Provinces%2C_A.D._1654.jpg)

After the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and Act of Settlement in 1652, the lands of most Irish Catholic land holders were confiscated and they were banned from living in planted towns. An unknown number, possibly as high as 100,000 Irish were removed to the colonies in the West Indies and North America as indentured servants.[13]

In addition, the Crown supported a series of population transfers into Ireland, to enlarge the loyal, Protestant population of Ireland. These are known as the plantations, and migrants came chiefly from Scotland and the northern border counties of England. In the late eighteenth century, the Scots-Irish constituted the largest group of immigrants from the British Isles to enter the Thirteen Colonies before the American Revolutionary War.[14]

Scotland

The enclosures that depopulated rural England in the British Agricultural Revolution started during the Middle Ages. Similar developments in Scotland have lately been called the Lowland Clearances.

The Highland Clearances were forced displacements of the populations of the Scottish Highlands and Scottish Islands in the 18th century. They led to mass emigration to the coast, the Scottish Lowlands and abroad, including to the Thirteen Colonies, Canada and the Caribbean.

Central Europe

Historically, expulsions of Jews and of Romani people reflect the power of state control that has been applied as a tool, in the form of expulsion edicts, laws, mandates, etc., against them for centuries. The most famous such event was the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. Some of the Jews went to North Africa; others east into Poland, France and Italy, and other Mediterranean countries.

Another event, in 1609, was the Expulsion of the Moriscos, the final transfer of 300,000 Muslims out of Spain, after more than a century of Catholic trials, segregation, and religious restrictions. Most of the Spanish Muslims went to North Africa and to areas of Ottoman Empire control.[15]

After the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact divided Poland during World War II, Germans deported Poles and Jews from Polish territories annexed by Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union deported Poles from areas of Eastern Poland, Kresy to Siberia and Kazakhstan. From 1940, Hitler tried to get Germans to resettle from the areas in which they were the minority (the Baltics, South-Eastern and Eastern Europe) to the Warthegau, the region around Poznań, German Posen. He expelled the Poles and Jews who formed there the majority of the population. Before the war, the Germans were 16% of the population in the area.[16]

The Nazis initially tried to press Jews to emigrate. In Austria, they succeeded in driving out most of the Jewish population. However, increasing foreign resistance brought this plan to a virtual halt. Later on, Jews were transferred to ghettoes and eventually to death camps. Use of forced labor in Nazi Germany during World War II occurred on a large scale. The Germans abducted about 12 million people from almost twenty European countries; about two-thirds of whom came from Eastern Europe.[17]

After World War II, when the Curzon line proposed in 1919 by the Western Allies as Poland's eastern border war implemented, members of all ethnic groups were transferred to their respective new territories (Poles to Poland, Ukrainians to Soviet Ukraine). The same applied to the former German territories east of the Oder-Neisse line, where German citizens were transferred to Germany. Germans were expelled from areas annexed by the Soviet Union and Poland as well as territories of Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania and Yugoslavia.[18] From 1944 until 1948, between 13.5 and 16.5 million Germans were expelled, evacuated or fled from Central and Eastern Europe. The Statistisches Bundesamt estimates the loss of life at 2.1 million [19]

Poland and Soviet Ukraine conducted population exchanges—Poles that resided east of the established Poland-Soviet border were deported to Poland (approx. 2,100,000 persons) and Ukrainians that resided west of the established Poland-Soviet Union border were deported to Soviet Ukraine. Population transfer to Soviet Ukraine occurred from September 1944 to May 1946 (approx. 450,000 persons). Some Ukrainians (approx. 200,000 persons) left southeast Poland more or less voluntarily (between 1944 and 1945).[20] The second event occurred in 1947 under Operation Vistula.[21]

Nearly 20 million people in Europe fled their homes, were expelled, transferred or exchanged during the process of sorting out ethnic groups between 1944 and 1951.[22]

Southeastern Europe

In September 1940 with the return of Southern Dobruja (the Cadrilater) by Romania to Bulgaria under the Treaty of Craiova, 80,000 Romanians were compelled to move north of the border, while 65,000 Bulgarians living in Northern Dobruja were forced to move into Bulgaria.

Around 360,000 Bulgarian Turks fled Bulgaria during the Revival Process.[23]

During the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s, the breakup of Yugoslavia caused large population transfers, mostly involuntary. As it was a conflict fueled by ethnic nationalism, people of minority ethnicities generally fled towards regions that their ethnicity was the majority.

The phenomenon of "ethnic cleansing" was first seen in Croatia but soon spread to Bosnia. Since the Bosnian Muslims had no immediate refuge, they were arguably the hardest hit by the ethnic violence. United Nations tried to create safe areas for Muslim populations of eastern Bosnia but in the Srebrenica massacre and elsewhere, the peacekeeping troops failed to protect the safe areas, resulting in the massacre of thousands of Muslims.

The Dayton Accords ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, fixing the borders between the two warring parties roughly to those established by the autumn of 1995. One immediate result of the population transfer after the peace deal was a sharp decline in ethnic violence in the region.

See Washington Post Balkan Report for a summary of the conflict, and FAS analysis of former Yugoslavia for population ethnic distribution maps.

A massive and systematic deportation of Serbia's Albanians took place during the Kosovo War of 1999, with around 800,000 Albanians (out of a population of about 1.5 million) forced to flee Kosovo.[24] Albanians became the majority in Kosovo at the wars end, around 200,000 Serbs and Roma fled Kosovo. When Kosovo proclaimed independence in 2008, the bulk of its population was Albanian.[25]

A number of commanders and politicians, notably Serbia and Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević, were put on trial by the UN's International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia for a variety of war crimes, including deportations and genocide.

Turkey and Greece

The League of Nations defined those to be mutually expelled as the "Muslim inhabitants of Greece" to Turkey and moving "the Christian Orthodox inhabitants of Turkey" to Greece. The plan met with fierce opposition in both countries and was condemned vigorously by a large number of countries. Undeterred, Fridtjof Nansen worked with both Greece and Turkey to gain their acceptance of the proposed population exchange. About 1.5 million Christians and half a million Muslims were moved from one side of the international border to the other.

When the exchange was to take effect (1 May 1923), most of the prewar Orthodox Greek population of Aegean Turkey had already fled and so only the Orthodox Christians of central Anatolia (both Greek and Turkish-speaking), and the Greeks of Pontus were involved, a total of roughly 189,916.[26] The total number of Muslims involved was 354,647.[27]

The population transfer prevented further attacks on minorities in the respective states, and Nansen was awarded a Nobel Prize for Peace. As a result of the transfers, the Muslim minority in Greece and the Greek minority in Turkey were much reduced. Cyprus and the Dodecanese were not included in the Greco-Turkish population transfer of 1923 because they were under direct British and Italian control respectively. For the fate of Cyprus, see below. The Dodecanese became part of Greece in 1947.

Italy

Between 1924 and 1945, Benito Mussolini's Fascist government forced minorities living in Italy to accept the Italian language and culture, and he worked to erase any traces of the existence of other nations on the territory of Italy.

Italianization aimed to suppress the native non-Italian populations living in Italy. The affected populations were Slovenes and Croats in the Julian March, Lastovo and Zadar; between 1941 and 1943 the Gorski Kotar and coastal Dalmatia; German-speakers in South Tyrol, parts of Friuli and the Julian March, Francoprovençal-speaking peoples in the Aosta Valley, as well as Greeks, Turks and Jews on the Dodecanese islands.

In 1939, Hitler and Mussolini agreed to give the German-speaking population of South Tyrol a choice (the South Tyrol Option Agreement): they could emigrate to neighbouring Germany (including the recently-annexed Austria) or stay in Italy and accept to be assimilated. Because of the outbreak of World War II, the agreement was only partially consummated.

Meanwhile, in the Aosta Valley, Italianization was forced, with population transfers of Valdostans into Piedmont and Italian-speaking workers into Aosta, fostering movements towards separatism.

Cyprus

After the Turkish invasion of Cyprus and subsequent division of the island, there was an agreement between the Greek representative on one side and the Turkish Cypriot representative on the other side, under the auspices of the United Nations on August 2, 1975 under which the Government of the Republic of Cyprus would lift any restrictions in the voluntary movement of Turkish Cypriots to the Turkish-occupied areas of the island and in exchange, the Turkish Cypriot side would allow all Greek Cypriots who remained in the occupied areas to stay there and to be given every help to live a normal life.[28]

Soviet Union

Shortly before, during and immediately after World War II, Stalin conducted a series of deportations on a huge scale, which profoundly affected the ethnic map of the Soviet Union. Over 1.5 million people were deported to Siberia and the Central Asian republics. Separatism, resistance to Soviet rule and collaboration with the invading Germans were cited as the main official reasons for the deportations. After World War II, the population of East Prussia was replaced by the Soviet one, mainly by Russians. Many Tartari Muslims were transferred to Northern Crimea, now Ukraine, while Southern Crimea and Yalta were populated with Russians.

One of the conclusions of the Yalta Conference was that the Allies would return all Soviet citizens that found themselves in the Allied zone to the Soviet Union (Operation Keelhaul). That immediately affected the Soviet prisoners of war liberated by the Allies, but was also extended to all Eastern European refugees. Outlining the plan to force refugees to return to the Soviet Union, the codicil was kept secret from the American and British people for over 50 years.[29]

In the Americas

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire dispersed conquered ethnic groups throughout the empire to break down traditional community ties and force the heterogeneous population to adopt the Quechua language and culture. Never fully successful in the pre-Columbian era, the totalitarian policies had their greatest success when they were adopted, from the 16th century, to create a pan-Andean identity defined against Spanish rule. Much of the current knowledge of Inca population transfers comes from their description by the Spanish chroniclers Pedro Cieza de León and Bernabé Cobo.

Canada

During the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years' War between Great Britain and France), the British forcibly relocated approximately 8,000 Acadians from the Canadian Maritime Provinces, first to the Thirteen Colonies and then to France. Thousands died of drowning, starvation, or illness as a result of the deportation. Some of the Acadians who had been relocated to France then emigrated to Louisiana, where their descendants became known as Cajuns.

The High Arctic relocation took place during the Cold War in the 1950s, when 87 Inuit were moved by the Government of Canada to the High Arctic. The relocation has been a source of controversy: described as either a humanitarian gesture to save the lives of starving native people or a forced migration instigated by the federal government to assert its sovereignty in the Far North against the Soviet Union. Both sides acknowledge that the relocated Inuit were not given sufficient support.

Numerous other indigenous peoples of Canada have been forced to relocate their communities to different reserve lands, including the 'Nak'waxda'xw in 1964.

Japanese Canadian internment

Japanese Canadian Internment refers to the detainment of Japanese Canadians following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Canadian declaration of war on Japan during World War II. The forced relocation subjected Japanese Canadians to government-enforced curfews and interrogations and job and property losses. The internment of Japanese Canadians was ordered by Prime Minister Mackenzie King, largely because of existing racism. However, evidence supplied by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Department of National Defence show that the decision was unwarranted.

Until 1949, four years after World War II had ended, all persons of Japanese heritage were systematically removed from their homes and businesses and sent to internment camps. The Canadian government shut down all Japanese-language newspapers, took possession of businesses and fishing boats, and effectively sold them. To fund the internment itself, vehicles, houses, and personal belongings were also sold.

United States

Independence

During and after the American Revolutionary War, many Loyalists were deprived of life, liberty or property or suffered lesser physical harm, sometimes under acts of attainder and sometimes by main force. Parker Wickham and other Loyalists developed a well-founded fear. As a result, many chose or were forced to leave their former homes in what became the United States, often going to Canada, where the Crown promised them land in an effort at compensation and resettlement. Most were given land on the frontier in what became Upper Canada and had to create new towns. The communities were largely settled by people of the same ethnic ancestry and religious faith. In some cases, towns were started by men of particular military units and their families.

Native American relocations

In the 19th century, the United States government removed a number of Native Americans to federally-owned and -designated Indian reservations. Native Americans were removed from the Northern to the Western States. The most well-known removals were those of the 1830s from the Southeast, starting with the Choctaw people. Under the 1830 Indian Removal Act, the Five Civilized Tribes were relocated from their place, east of the Mississippi River, to the Indian Territory in the west. The process resulted in great social dislocation for all, numerous deaths, and the "Trail of Tears" for the Cherokee Nation. Resistance to Indian removal led to several violent conflicts, including the Second Seminole War in Florida.

The Long Walk of the Navajo refers to the 1864 relocation of the Navajo people by the US government in a forced walk from their land in what is now Arizona to eastern New Mexico. The Yavapai people were forcibly marched from Camp Verde Reservation to San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, Arizona, on February 27, 1875, following the Yavapai War. The federal government restricted Plains Indians to reservations following several Indian Wars in which Indians and European Americans fought over lands and resources. Indian prisoners of war were held at Fort Marion and Fort Pickens in Florida.

General Order No. 11 (1863)

General Order No. 11 is the title of a Union Army decree issued during the American Civil War on 25 August 1863, forcing the evacuation of rural areas in four counties in western Missouri. That followed extensive insurgency and guerrilla warfare. The Army cleared the area to deprive the guerrillas of local support. Union General Thomas Ewing issued the order, which affected all rural residents regardless of their loyalty. Those who could prove their loyalty to the Union were permitted to stay in the region but had to leave their farms and move to communities near military outposts. Those who could not do so had to vacate the area altogether.

In the process, Union forces caused considerable property destruction and deaths because of conflicts.

Japanese American internment

In the wake of Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and with decades-long suspicions and antagonism to ethnic Japanese mounting, the US government ordered military forcible relocation and internment of approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese residing in the United States to newly created "War Relocation Camps," or internment camps, in 1942 for of the war. European Americans often bought their property at losses.

Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans residing on the West Coast of the United States were all interned. In Hawaii, where more than 150,000 Japanese Americans composed nearly a third of that territory's population, officials interned only 1,200 to 1,800 Japanese Americans. In the late 20th century, the US government paid some compensation to survivors of the internment camps.

In Asia

Ottoman Empire

The early Ottoman Empire used forced population transfers to change the ethnic and economic landscape of its territories. The term used in Ottoman documents is sürgün, from sürmek (to displace).

Ottoman population transfers until the reign of Mehmet I (d. 1421) shuttled tribal Turkmen and Tatar groups from the state's Asiatic territories to the Balkans (Rumeli). Many of the groups were supported as paramilitary forces along the frontier with Christian Europe. Simultaneously, Christian communities were transported from newly conquered lands in the Balkans into Thrace and Anatolia. While the general flows back and forth across the Dardanelles continued, Murad II (d. 1451) and Mehmet II (d. 1481) concentrated on the demographic reorganization of their empire's urban centres. Murad II's conquest of Salonika was followed by its state-enforced settlement of Muslims to Yenice Vardar from Anatolia. Mehmet II's transfers focused on the repopulation of Constantinople, following its conquest in 1453, transporting Christians, Muslims, and Jews into the new capital from across the empire. The huge Belgrade Forest north of Istanbul and named after re-settled people from Belgrade is a reminder of those times. Also, the Belgrade Gate is on the east side of the city, on the way to Serbia.

From Bayezid II (d. 1512), the empire had difficulty with the heterodox Qizilbash (kizilbas) movement in eastern Anatolia. Forced relocation of the Qizilbash continued until at least the end of the 16th century. Selim I (d. 1520) ordered merchants, artisans, and scholars transported to Constantinople from Tabriz and Cairo. The state mandated Muslim immigration to Rhodes and Cyprus after their conquests in 1522 and 1571 respectively and resettled Greek Cypriots onto Anatolia's coast.

Knowledge among western historians about the use of sürgün from the 17th through the 19th century is somewhat unreliable. It appears that the state did not use forced population transfers as much as during its expansionist period.[30]

After the exchanges in the Balkans, the Great Powers and then the League of Nations used forced population transfer as a mechanism for homogeneity in post-Ottoman Balkan states to decrease conflict. A Norwegian diplomat, working with the League of Nations as a High Commissioner for Refugees in 1919, proposed the idea of a forced population transfer. That was modelled on the earlier Greek-Bulgarian mandatory population transfer of Greeks in Bulgaria to Greece and of Bulgarians in Greece to Bulgaria.

In his 2007 book, Israeli scholar Mordechai Zaken discussed the history of the Assyrian Christians of Turkey and Iraq (in Iraqi Kurdistan) since 1842.[31] Zaken identified three major eruptions that took place between 1843 and 1933 during which the Assyrian Christians lost their land and hegemony in the Hakkārī (or Julamerk) region in southeastern Turkey and became refugees in other lands, notably Iran and Iraq. They also formed exiled communities in European and western countries (including the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden and France, to mention some of the countries). The Assyrian Christians migrated in stages following each political crisis. Millions of Assyrian Christians live today in exiled and prosperous communities in the West.[32]

Palestine

Both Jews and Arabs evacuated certain communities in former British Mandate of Palestine after Israel has been attacked by Arab countries in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The part of British Mandate occupied by Jordan and Egypt was ethnically cleansed with no Jewish population left. Jewish inhabitants of communities like Gush Etzion, Hebron and Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem were absorbed by the new State of Israel.[33][34][35]

The Palestinian exodus (also known as the Nakba) of approximately 711,000 to 725,000 from the British mandate of Palestine occurred in the months leading up to and during the 1948 Palestine War[36]. The bulk of the Arab refugees from the former British Mandate of Palestine ended up in the Gaza Strip (under Egyptian rule between 1949 and 1967) and the West Bank (under Jordanian rule between 1949 and 1967), Jordan, Syria and Lebanon.[37]

During the 1948 Palestine war, the Haganah devised Plan Dalet, which some scholars interpret to have been primarily aimed at ensuring the expulsion of Palestinians,[38][39] but that interpretation is disputed. Efraim Karsh states that most of the Arabs who fled left of their own accord or were pressured to leave by their fellow Arabs despite Israeli attempts to convince them to stay.[40][41][42][43][44]

The idea of the transfer of Arabs from Palestine had been considered about half a century beforehand.[45][46]

For example, Theodor Herzl wrote in his diary in 1895 that the Zionist movement "shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our country," but that comment did not specifically relate to Palestine.[47][48] Forty years later, one of the recommendations in the Report of the British Peel Commission in 1937 was for a transfer of Arabs from the area of the proposed Jewish state, and it even included a compulsory transfer from the plains of Palestine. That recommendation was not initially objected to by the British Government.[49]

The British plan was never endorsed by the Zionists, and transfer was never official Zionist policy,[44][50][51] but many senior Zionists supported the concept in private.[52]

Scholars have debated David Ben-Gurion's views on transfer, particularly in the context of the 1937 Ben-Gurion letter, but according to Benny Morris, Ben-Gurion "elsewhere, in unassailable statements... repeatedly endorsed the idea of “transferring” (or expelling) Arabs, or the Arabs, out of the area of the Jewish state-to-be, either "voluntarily" or by compulsion."[53]

Persia

Removal of populations from along their borders with the Ottomans in Kurdistan and the Caucasus was of strategic importance to the Safavids. Hundreds of thousands of Kurds, along with large groups of Armenians, Assyrians, Azeris, and Turkmens, were forcibly removed from the border regions and resettled in the interior of Persia. That was a means of cutting off contact with other members of the groups across the borders as well as limiting passage of peoples. The Khurasani Kurds are a community of nearly 1.7 million people deported from western Kurdistan to North Khorasan, (northeastern Iran) by Persia during the 16th to the 18th centuries.[54] For a map of these areas see.[55] Some Kurdish tribes were deported farther east, into Gharjistan in the Hindu Kush mountains of Afghanistan, about 1500 miles away from their former homes in western Kurdistan (see Displacement of the Kurds).

Ancient Assyria

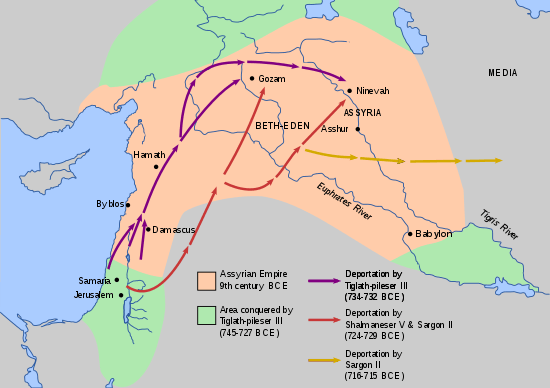

In the Ancient World, population transfer was the more humane alternative to putting all the males of a conquered territory to death and enslaving the women and children. From the 13th century BCE, Ancient Assyria used mass deportation as a punishment for rebellions. By the 9th century BCE, the Assyrians regularly deported thousands of restless subjects to other lands. The Israelite tribes that were forcibly resettled by Assyria later became known as the Ten Lost Tribes. The Hittites often transferred populations of defeated peoples back to Hatti. (Trevor Bryce, The Kingdom of the Hittites) The deportation of the elite of the Jews of Jerusalem on three occasions during the Babylonian captivity in the 6th century BCE was a population transfer.

Indian Subcontinent

When British India became independent after the Second World War, some of its Muslim inhabitants demanded their own state consisting of two non-contiguous territories: East Pakistan and West Pakistan. To facilitate the creation of new states along religious lines (as opposed to racial or linguistic lines as people shared common histories and languages), Population exchanges between India and Pakistan were implemented. More than 5 million Hindus and Sikhs were forced to move from present-day Pakistan to present-day India, and the same number of Muslims moved the other way. A large number of people, more than a million by some estimates, died in the accompanying violence. Despite the movement of large number of Muslims to Pakistan, an equal number of Muslims chose to stay in India. However, most of the Hindu and Sikh population in Pakistan moved to India in the following years.

In 1992, the ethnic Hindu Kashmiri Pandit population was forcibly moved out of Kashmir by a minority Urdu-speaking Muslims. The imposition of Urdu led to a decline of usage of local languages such as Kashmiri and Dogri. The resultant violence led to the death of many Hindus and the exodus of nearly all Hindus.

On the Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia between 1967 and 1973, the British government forcibly removed 2000 Chagossian islanders to make way for a military base. Despite court judgments in their favour, they have not been allowed to return from their exile in Mauritius, but there are signs that financial compensation and an official apology are being considered by the British government.

Afghanistan

In the 1880s, Abdur Rahman Khan moved the rebellious Ghilzai Pashtuns from the southern part of the country to the northern part.[56][57] In addition, Abdur Rahman and his successors encouraged Pashtuns, with various incentives, to settle into northern Afghanistan in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

Cambodia

One of the Khmer Rouge's first acts was to move most of the urban population into the countryside. Phnom Penh, its population of 2.5 million people including as many as 1.5 million wartime refugees living with relatives or in urban area, was soon nearly empty. Similar evacuations occurred at Battambang, Kampong Cham, Siem Reap, Kampong Thom and throughout the country's other towns and cities. The Khmer Rouge attempted to turn Cambodia into a classless society by depopulating cities and forcing the urban population ("New People") into agricultural communes. The entire population was forced to become farmers in labor camps.

Caucasia

In the Caucasian region of the former Soviet Union, ethnic population transfers have affected many thousands of individuals in Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan proper; in Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Georgia proper and in Chechnya and adjacent areas within Russia.

Middle East

- During the Kurdish rebellions in Turkey from 1920 and until 1937, hundreds of thousands of Kurdish refugees were forced to relocate.

- After the creation of the State of Israel and the Israel Independence War, a strong wave of anti-Semitism in the Arab countries forced many Jews to flee to Europe, the Americas and Israel. The number estimated is between 850,000 and 1,000,000 people. Those who arrived to Israel were put in a refugee camps until the state had helped them to recover.[58][59]

- Up to 3,000,000 people, mainly Kurds, have been displaced in the Kurdish–Turkish conflict,[60] an estimated 1,000,000 of which were still internally displaced as of 2009.[61]

- For decades, Saddam Hussein forcibly Arabized northern Iraq.[62] Sunni Arabs drove out at least 70,000 Kurds from western Mosul to replace them with Sunni Arabs.[63] Now, only eastern Mosul is Kurdish.[64]

- During the First Gulf War, a survey reported that 732,000 Yemeni immigrants were forced to leave Gulf Countries to return to Yemen. Most of them had been in Saudi Arabia.[65]

- After the First Gulf War, Kuwaiti authorities expelled nearly 200,000 Palestinians from Kuwait.[66] That was partly a response to the alignment of PLO leader Yasser Arafat with Saddam Hussein.

- About 2 million Iraqi refugees fled the country during the Iraq War of 2003 to 2011, mostly because of sectarian violence, the largest group being Assyrian Christians.

- In August 2005, Israel forcibly transferred all 10,000 Israeli settlers from the Gaza Strip and the north of the West Bank.[67][68][69][70]

- About 6.5 million Syrian refugees moved within the country, and 4.3 million left for neighboring countries because of the Syrian Civil War. Many were displaced by the fighting, with forced expulsions taking place against both Sunni Arabs and Alawites.[71]

See also

- Deportation

- Ethnic cleansing

- Forced migration

- Fred Korematsu

- Development-induced displacement

- Highland Clearances (Scotland)

- Madagascar Plan

- Partition of India

- Pashtun colonization of northern Afghanistan

- Political migration

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Refugee

- Slave trade

- Villagization

- Third country resettlement

- Voluntary return

References

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2013-12-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Finkelstein, Norman Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict, 2nd ed. (Verso, 2003) p.xiv – also An Introduction to the Israel-Palestine Conflict Archived 2008-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Alfred de Zayas, Nemesis at Potsdam, Routledge 1979, Appendix pp. 232–234, and A Terrible Revenge, Macmillan 2006, pp.86–87

- Alfred de Zayas, Forced Population Transfer, in: Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, online 2009, with reference to Articles 6b and 6c of the Nuremberg indictment and the relevant parts of the judgment concerning the forced transfer of Poles and Frenchmen by the Nazis

- Denver Journal of International Law and Policy, Spring 2001, p 116.

- Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949.Commentary on Part III : Status and treatment of protected persons #Section III : Occupied territories Art. 49 Archived 2006-05-05 at the Wayback Machine by the ICRC

- "unhchr.ch". www.unhchr.ch. Archived from the original on 2005-12-04.

- "unhchr.ch". www.unhchr.ch. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29.

- Fussell, Jim. "Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Articles 1 to 33)- Prevent Genocide International". www.preventgenocide.org. Archived from the original on 2015-05-13.

- Timothy V. Waters, On the Legal Construction of Ethnic Cleansing Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Paper 951, 2006, University of Mississippi School of Law. Retrieved on 2006, 12–13

- Gilbert Gornig (ed.) Eigentumsrecht und Enteignungsunrecht, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2009, pp. 213–242.

- Sertima, Ivan Van (1986-01-01). African Presence in Early Europe. Transaction Books. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-88738-664-0. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

Louis XV, in an effort to stop the mass influx of blacks into Paris, ordered all blacks deported from France. This did not, in fact, take place.

- The Curse of Cromwell Archived 2012-03-02 at the Wayback Machine, A Short History of Northern Ireland, BBC

- David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America

- José Manuel Fajardo, Opinion: "Moriscos: el mayor exilio español" Archived 2012-07-18 at the Wayback Machine, El Païs, 2 Ene (January) 2009, in Spanish, accessed 8 December 2012

- Kulischer, Eugene M. (28 October 2017). The Displacement Of Population In Europe. The International labour Office – via Internet Archive.

- "Final Compensation Pending for Former Nazi Forced Laborers - DW - 27.10.2005". DW.COM. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- "refugee". Archived from the original on 2008-10-07.

- Statistisches Bundesamt, Die Deutschen Vertreibungsverluste, Wiesbaden 1958, see also Gerhard Reichling "Die deutschen Vertriebenen in Zahlen", vol. 1–2, Bonn 1986/89.

- "Forced migration in the 20th century". Archived from the original on 2015-10-21.

- The Euromosaic study: Ukrainian in Poland Archived 2008-02-22 at the Wayback Machine. European Commission, October 2006.

- Schechtman, Joseph B. (28 October 2017). "Postwar Population Transfers in Europe: A Survey". The Review of Politics. 15 (2): 151–178. JSTOR 1405220.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2018. Ethnic Cleansing During the Cold War: The Forgoten 1989 Expulsion of Turks from Communist Bulgaria (Ser: Routledge Studies in Modern European History). London: Routledge, 328pp. ISBN 9781138480520

- "Europe :: Kosovo — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- "Serbia | History, Geography, & People". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- Matthew J. Gibney, Randall Hansen. (2005). Immigration and asylum: from 1900 to the present, Volume 3. ABC-CLIO. p. 377. ISBN 978-1-57607-796-2.

- Renée Hirschon. (2003). Crossing the Aegean: an appraisal of the 1923 compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Berghahn Books. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-57181-562-0.

- United Nations, Text of the Press Communique on the Cyprus Talks Issued in Vienna on 2 August 1975 Archived 2 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine United Nations, Text of the Press Communique on the Cyprus Talks Issued in Vienna on 2 August 1975.

- Jacob Hornberger Repatriation — The Dark Side of World War II. The Future of Freedom Foundation, 1995. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-01-17. Retrieved 2014-01-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- P. Hooper, Thesis Archived 2008-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, University of New Mexico

- Mordechai Zaken, Jewish Subjects and Their Tribal Chieftains in Kurdistan: A Study in Survival, Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2007. Based on his 2004 doctoratw thesis, Tribal Chieftains and Their Jewish Subjects: A Comparative Study in Survival'', The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2004.

- An early source on the Jews of Kurdistan was Erich Brauer, The Jews of Kurdistan, 1940, revised edition 1993, edited by Raphael Patai, Wayne State University Press, Detroit

- "Ethnic cleansing of Jews by Arabs in pre-state Israel". www.science.co.il. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Milstein, U. "History of the War of Independence: The first month Archived 2018-01-15 at the Wayback Machine"

- A Just Zionism: On the Morality of the Jewish State, Gans C, Oxford University Press "" Archived 2018-01-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Rosemarie M. Esber Under the Cover of War: The Zionist Expulsion of the Palestinians. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/arab-league-declarationon-the-invasion-of-palestine-may-1948

- Ilan Pappe (2006), The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oxford: Oneworld

- Pappé, 2006, pp. 86–126, xii, "this… blueprint spelled it out clearly and unambiguously: the Palestinians had to... each brigade commander received a list of the villages or neighborhoods that had to be occupied, destroyed, and their inhabitants expelled"

- Khalidi, W. "Plan Dalet: master plan for the conquest of Palestine Archived 2017-08-19 at the Wayback Machine", J. Palestine Studies 18 (1), 1988, p. 4-33 (published earlier in Middle East Forum, November 1961)

- Karsh, Efraim. "Were the Palestinians Expelled?" (PDF). Commentary. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2014. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- Karsh, Efraim (June 1996). "Rewriting Israel's History". Middle East Quarterly. The Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 2014-07-22. Retrieved 2014-08-10.

- Karsh, Efraim (2008-05-01). "1948, Israel, and the Palestinians-The True Story". Commentary. Archived from the original on 2014-08-07. Retrieved 2014-08-10.

- cf. Teveth, Shabtai (April 1990). "The Palestine Arab Refugee Problem and Its Origins". Middle Eastern Studies. 26 (2): 214–249. doi:10.1080/00263209008700816. JSTOR 4283366.

- Rodman, David (Summer 2010). "Review of Palestine Betrayed". Middle East Quarterly. The Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2014-08-10.

By mining Jewish, Arab, and British documents, Karsh demonstrates conclusively that in many places, especially in the mixed cities during the civil phase of the war (November 1947—May 1948), the local Jewish authorities repeatedly and sincerely urged the Palestinian Arab leadership and public to remain in their residences and live in peace with their Jewish neighbors. Those Arab city dwellers and villagers who took this advice—and there were apparently quite a few villages that entered into "non-aggression" pacts with their Jewish neighbors—were almost always left alone by Jewish forces. Karsh concedes that some Palestinian Arabs were driven out of their homes by Jewish forces with the only large-scale incidents taking place in the towns of Lod and Ramle. However, these expulsions were carried out on grounds of military necessity, were not part of any premeditated "transfer" policy, and involved a relatively small percentage of the total refugee population. These removals, one might add, were directed principally against Palestinian Arabs who had taken an active part in the war and who constituted an immediate threat to nearby Jewish populations or lines of communication.

- A Historical Survey of Proposals to Transfer Arabs from Palestine, 1895–1947, Dr. Chaim Simons, 2003

- Benny Morris, Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881–1999 (New York, 1999), p. 139, "For many Zionists, beginning with Herzl, the only realistic solution lay in transfer. From 1880 to 1920, some entertained the prospect of Jews and Arabs coexisting in peace. But increasingly after 1920, and more emphatically after 1929, for the vast majority a denouement of conflict appeared inescapable. Following the outbreak of 1936, no mainstream leader was able to conceive of future coexistence and peace without a clear physical separation between the two peoples—achievable only by way of transfer and expulsion.”

- The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, vol. 1 (New York: Herzl Press and Thomas Yoseloff, 1960), pp. 88, 90

- That interpretation of Herzl has been disputed. See Alexander, Edward; Bogdanor, Paul (2006). The Jewish Divide Over Israel. Transaction. pp. 251–2.

[The diary entry] had already been a feature of Palestinian propaganda for decades.... Any discussion of relocation was clearly limited to the specific lands assigned to the Jews, rather than the entire territory. Had Herzl envisaged the mass expulsion of population... there would have been no need to discuss its position in the Jewish entity.

- Morris (2003), The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, chapter: The Idea of Transfer in Zionist Thinking

- Alexander, Edward; Bogdanor, Paul (2006). The Jewish Divide Over Israel. Transaction. pp. 254, 258.

There was never any Zionist attempt to inculcate the "transfer" idea in the hearts and minds of Jews. [Morris] could find no evidence of any press campaign, radio broadcasts, public rallies, or political gatherings, for none existed.

- Laquer, Walter (1972). A History of Zionism. Random House. pp. 231–232.

[Ruppin] suggested... a limited population transfer. The Zionists would buy land near Aleppo and Homs in northern Syria for the resettlement of Arab peasants who had been dispossessed in Palestine. But this was vetoed because it was bound to increase Arab suspicions over Zionist intentions.... The concept of an "Arab trek" to their own Arabian state played a central part in [Zangwill's] scheme. Of course, the Arabs would not be compelled to do so, it would all be agreed upon in a friendly and amicable spirit.... But the idea of transfer was never official Zionist policy. Ben-Gurion emphatically rejected it.

- Chaim Simons (1988). International Proposals to Transfer Arabs from Palestine 1895–1947: A Historical Survey. Ktav Pub Inc. ISBN 978-0881253009.

Very few people have had the courage to support publicly the transfer of Arabs from Palestine. Most leaders of the Zionist movement publicly opposed such transfers. However, a study of their confidential correspondence, private diaries, and minutes of closed meetings, made available to the public under the "thirty year rule," reveals the true feelings of the Zionist leaders on the transfer question. We see from this classified material that Herzl, Ben-Gurion, Weizmann, Sharett, and Ben-Zvi, to mention just a few, were really in favor of transferring the Arabs from Palestine.

Also quoted in Mark A. Tessler (1 January 1994). A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Indiana University Press. pp. 784 note 113. ISBN 978-0-253-20873-6. - Michael Rubin and Benny Morris (2011), Quoting Ben Gurion: An Exchange Archived 2014-10-20 at the Wayback Machine, Commentary (magazine), quote: "...the focus by my critics on this quotation was, in any event, nothing more than (an essentially mendacious) red herring – as elsewhere, in unassailable statements, Ben-Gurion at this time repeatedly endorsed the idea of “transferring” (or expelling) Arabs, or the Arabs, out of the area of the Jewish state-to-be, either “voluntarily” or by compulsion."

- Izady, Mehrdad R., The Kurds: A Concise Handbook, Taylor & Francis, Washington, D.C., 1992

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2015-10-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Peter Tomsen, The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic Terrorism, Tribal Conflicts, and the Failures of Great Powers, (Public Affairs: 2011), p. 42.

- Edward Girardet, Killing the Cranes, London: Chelsea Green

- "Jews (JIMENA)|JIMENA's Mission and History Archived 2014-10-25 at the Wayback Machine". JIMENA. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa Archived 2013-03-07 at the Wayback Machine (JIMENA)

- "Conflict Studies Journal at the University of New Brunswick". Lib.unb.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-10-13. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) – Norwegian Refugee Council. "Need for continued improvement in response to protracted displacement". Internal-displacement.org. Archived from the original on 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2011-04-15.

- "Claims in Conflict: Reversing Ethnic Cleansing in Northern Iraq: III. Background". www.hrw.org. Archived from the original on 2015-11-18.

- "Breaking News, World News & Multimedia". Archived from the original on 2014-01-08.

- The other Iraqi civil war, Asia Times

- United Nation Publication, 2003. Levels and Trends of International Migration to Selected Countries. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs p. 37. Available at:"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Steven J. Rosen (2012). "Kuwait Expels Thousands of Palestinians". Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 2013-05-11.

From March to September 1991, about 200,000 Palestinians were expelled from the emirate in a systematic campaign of terror, violence, and economic pressure while another 200,000 who fled during the Iraqi occupation were denied return.

- Resolution 446, Resolution 465, Resolution 484, among others

- "Applicability of the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, of 12 August 1949, to the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem, and the other occupied Arab territories". United Nations. December 17, 2003. Archived from the original on 3 June 2007. Retrieved 2006-09-27.

- "Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory". International Court of Justice. July 9, 2004. Archived from the original on August 28, 2007. Retrieved 2006-09-27.

- "Conference of High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention: statement by the International Committee of the Red Cross". International Committee of the Red Cross. December 5, 2001. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-27.

- "2015 UNHCR country operations profile – Syrian Arab Republic". 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-02-10.

- Sonn, Tamara (2004). A Brief History of Islam. Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4051-0900-0.

Further reading

- Frank, Matthew. Making Minorities History: Population Transfer in Twentieth-Century Europe (Oxford UP, 2017). 464 pp. online review

- A. de Zayas, "International Law and Mass Population Transfers," Harvard International Law Journal 207 (1975).

- A. de Zayas, "The Right to the Homeland, Ethnic Cleansing and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia," Criminal Law Forum, Vol. 6, 1995, pp. 257–314.

- A. de Zayas, Nemesis at Potsdam, London 1977.

- A. de Zayas, A Terrible Revenge, Palgrave/Macmillan, New York, 1994. ISBN 1-4039-7308-3.

- A. de Zayas, Die deutschen Vertriebenen, Graz 2006. ISBN 3-902475-15-3.

- A. de Zayas, Heimatrecht ist Menschenrecht, München 2001. ISBN 3-8004-1416-3.

- N. Naimark, " Fires of Hatred," Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2001.

- U. Özsu, Formalizing Displacement: International Law and Population Transfers, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015.

- St. Prauser and A. Rees, The Expulsion of the "German" Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War, Florence, Italy, European University Institute, 2004.

External links

- Haslam, Emily. "Population, Expulsion and Transfer", Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

- UN Report, historical population transfers and exchanges (continues at bottom of page)

- Freedom of Movement – Human rights and population transfer, UN report on legal status of population transfers

- Paul Lovell Hooper, Forced Population Transfers in Early Ottoman Imperial Strategy, A Comparative Approach, 2003, senior thesis for BA degree, Princeton University

- "Medieval Jewish expulsions from French territories", Jewish Gates

- conceptwizard.com "History in a Nutshell", population transfer statistics in the Middle East

- Lausanne Treaty Emigrants Association