Marietta, Georgia

Marietta is located in central Cobb County, Georgia, United States,[5] and is the county's seat and largest city.

Marietta, Georgia City of Marietta | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Marietta Square | |

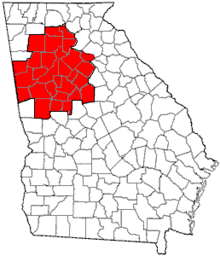

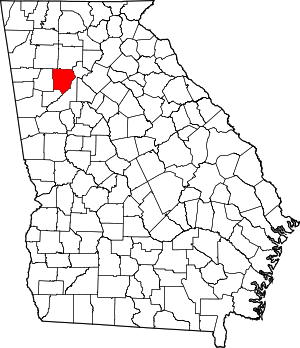

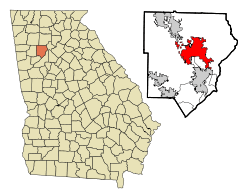

Location in Cobb County and the state of Georgia | |

Marietta Location of Marietta in Metro Atlanta | |

| Coordinates: 33°57′12″N 84°32′26″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Cobb |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | R. Steve Tumlin Jr. (R) |

| • City Manager | William F. Bruton Jr. |

| Area | |

| • Total | 23.48 sq mi (60.81 km2) |

| • Land | 23.41 sq mi (60.62 km2) |

| • Water | 0.07 sq mi (0.19 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,129 ft (344 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 56,579 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 60,867 |

| • Density | 2,600.49/sq mi (1,004.05/km2) |

| 2018 estimate | |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 30006-08, 30060-69, 30090 |

| Area code(s) | 770/678/470 |

| FIPS code | 13-49756[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0317694[4] |

| Website | www |

As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 56,579. The 2019 estimate is 60,867, making it one of Atlanta's largest suburbs. Marietta is the fourth largest of the principal cities (by population) of the Atlanta metropolitan area.[6][7]

History

Etymology

The origin of the name is uncertain. It is believed that the city was named for Mary Cobb, the wife of U.S. Senator and Superior Court judge Thomas Willis Cobb. Judge Cobb is the namesake of the county.[8]

Early settlers

Homes were built by early settlers near the Cherokee town of Big Shanty (now Kennesaw) prior to 1824.[9] The first plot was laid out in 1833. Like most towns, Marietta had a square (see Marietta Square) in the center with a courthouse. The Georgia General Assembly legally recognized the community on December 19, 1834.[9]

Built-in 1838, Oakton House[10] is the oldest continuously occupied residence in Marietta. The original barn, milk house, smokehouse, and well house remain on the property. The spectacular gardens contain the boxwood parterre from the 1870s. Oakton served as Major General Loring's headquarters during the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain in 1864.[11]

Marietta was initially selected as the hub for the new Western and Atlantic Railroad, and business boomed.[9] By 1838, roadbed and trestles had been built north of the city. However, in 1840, political wrangling stopped construction for a time. In 1842, the railroad's new management decided to move the hub from Marietta to an area that would become Atlanta. Nonetheless, in 1850, when the railroad began operation, Marietta shared in the resulting prosperity.[9]

Businessman and politician John Glover arrived in 1848. A popular figure, Glover was elected mayor when the city incorporated in 1852.[9] Another early resident was Carey Cox, a physician, who promoted a "water cure", that attracted tourists to the area. The Cobb County Medical Society recognizes him as the county's first physician.[9]

The Georgia Military Institute was built in 1851, and the first bank opened in 1855.[9] During the 1850s, fire destroyed much of the city on three separate occasions.[9]

Civil War

By the time the Civil War began in 1861, Marietta had recovered from the fires.[9]

In April 1862, James Andrews, a civilian working with the Union Army, came to Marietta, along with a small party of Union soldiers dressed in civilian clothing. The group spent the night in the Fletcher House hotel (later known as the Kennesaw House and now the home of the Marietta Museum of History) located immediately in front of the Western and Atlantic Railroad. Andrews and his men, who later became known as the Andrews Raiders, planned to seize a train and proceed north toward the city of Chattanooga, destroying the railroad on their way. They hoped, in so doing, to isolate Chattanooga from Atlanta and bring about the downfall of the Confederate stronghold. The Raiders boarded a waiting train on the morning of April 12, 1862, along with other passengers. Shortly after that, the train made a scheduled stop in the town of Big Shanty, now known as Kennesaw. When the other passengers got off the train for breakfast, Andrews and the Raiders stole the engine and the car behind it, which carried the fuel. The engine, called The General, and Andrews' Raiders had begun the episode now known as the Great Locomotive Chase.[9] Andrews and the Raiders failed in their mission. Andrews and all of his men were caught within two weeks, including two men who had arrived late and missed the hijacking. All were tried as spies, convicted, and hanged.[12]

General William Tecumseh Sherman invaded the town during the Atlanta Campaign in the summer of 1864. In November 1864, General Hugh Kilpatrick set the town ablaze, the first strike in Sherman's March to the Sea.[9] Sherman's troops crossed the Chattahoochee River at a shallow section known as the Palisades, after burning the Marietta Paper Mills near the mouth of Sope Creek.

The Marietta Confederate Cemetery, with the graves of over 3,000 Confederate soldiers killed during the Battle of Atlanta, is located in the city.[13]

In 1892, the city established a public school system. It included a high school for white students and a separate high school for black students.[14]

20th century

Leo Frank was lynched at 1200 Roswell Road just east of Marietta on August 17, 1915. Frank, a Jewish-American superintendent of the National Pencil Company in Atlanta, had been convicted on August 25, 1913, for the murder of one of his factory workers, 13-year-old Mary Phagan. The murder and trial, sensationalized in the local press, portrayed Frank as sexually depraved and captured the public's attention. An eleventh-hour commutation by Governor John Slaton of Frank's death sentence to life imprisonment (because of problems with the case against him) created great local outrage. A mob threatened the governor to the extent that the Georgia National Guard had to be called to defend him, and he left the state immediately with his political career over. Another mob, systematically organized for the purpose, abducted Frank from prison, drove him to Marietta, and hanged him. The leaders of the abduction included past, current, and future elected local, county, and state officials. There were two state legislators, the mayor, a former governor, a clergyman, two former Superior Court justices, and an ex-sheriff. In reaction Jewish activists created the Anti-Defamation League, to work to educate Americans about Jewish life and culture, and to prevent anti-Semitism.[15]

Marietta, Georgia is home of the Big Chicken, which was developed in 1963.

Geography

Located near the center of Cobb County, between Kennesaw to the northwest and Smyrna to the southeast. U.S. Route 41 and State Route 3 run through the city northeast of downtown as Cobb Parkway, and Interstate 75 runs parallel to it through the eastern part of Marietta, with access from exits 261, 263, 265, and 267. Downtown Atlanta is 20 miles (32 km) to the southeast, and Cartersville is 24 miles (39 km) to the northwest.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Marietta has a total area of 23.2 square miles (60.0 km2), of which 23.1 square miles (59.8 km2) is land and 0.077 square miles (0.2 km2), or 0.38%, is water.[6]

Climate

Marietta has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa).

Marietta falls under the USDA 7b Plant Hardiness zone.[16]

| Climate data for Marietta, Georgia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

80 (27) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

99 (37) |

92 (33) |

86 (30) |

80 (27) |

104 (40) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 52 (11) |

56 (13) |

64 (18) |

73 (23) |

80 (27) |

87 (31) |

89 (32) |

88 (31) |

83 (28) |

73 (23) |

64 (18) |

54 (12) |

72 (22) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 30 (−1) |

33 (1) |

39 (4) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

64 (18) |

68 (20) |

67 (19) |

60 (16) |

48 (9) |

39 (4) |

32 (0) |

48 (9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −12 (−24) |

−2 (−19) |

7 (−14) |

21 (−6) |

32 (0) |

40 (4) |

50 (10) |

48 (9) |

30 (−1) |

22 (−6) |

9 (−13) |

−4 (−20) |

−12 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.86 (123) |

5.36 (136) |

5.07 (129) |

3.93 (100) |

4.12 (105) |

4.07 (103) |

5.10 (130) |

4.35 (110) |

4.10 (104) |

3.42 (87) |

4.30 (109) |

4.49 (114) |

54.63 (1,388) |

| Source: [17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 1,888 | — | |

| 1880 | 2,227 | 18.0% | |

| 1890 | 3,384 | 52.0% | |

| 1900 | 4,446 | 31.4% | |

| 1910 | 5,949 | 33.8% | |

| 1920 | 6,190 | 4.1% | |

| 1930 | 7,638 | 23.4% | |

| 1940 | 8,667 | 13.5% | |

| 1950 | 20,687 | 138.7% | |

| 1960 | 25,565 | 23.6% | |

| 1970 | 27,216 | 6.5% | |

| 1980 | 30,805 | 13.2% | |

| 1990 | 44,129 | 43.3% | |

| 2000 | 58,748 | 33.1% | |

| 2010 | 56,579 | −3.7% | |

| Est. 2019 | 60,867 | [2] | 7.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 56,641 people, and 22,261 households.[3] The population density was 2,684.1 people per square mile (1,036.2/km2). There were 25,227 housing units at an average density of 1,152.6 per square mile (445.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 52.7% White, 31.5% African American, 0.1% Native American, 3.0% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 9.1% from other races, and 3.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 20.6% of the population.

There were 23,895 households out of which 27.8% had children under 18 living with them, 35.4% were married couples living together, 13.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.5% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39, and the average family size was 3.05.

In the city, the population was distributed by age with 22.4% under the age of 18, 14.1% from 18 to 24, 39.4% from 25 to 44, 15.7% from 45 to 64, and 8.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.3 males. For every 101 females age 18 and over, there were 100.3 males.

Government

Incorporated as a village in 1834 and as a city in 1852,[19] the city of Marietta is organized under a form of government consisting of a Mayor, City Council, and City Manager. The City Council is made up of representatives elected from each of seven single-member districts within the city, and a Mayor elected at-large.

The City Council is the governing body of the city with authority to adopt and enforce municipal laws and regulations. The Mayor and City Council appoint members of the community to sit on the city's various boards and commissions, ensuring that a broad cross-section of the town is represented in the city government.

The City Council appoints the City Manager, the city's chief executive officer. The Council-Manager relationship is comparable to that of a Board of Directors and CEO in a private company or corporation. The City Manager appoints city department heads and is responsible to the City Council for all city operations. The City Council also appoints the city attorney who serves as the city's chief legal officer and the City Clerk who maintains all the city's records.

Terms of office are for four years and the number of terms a member may serve are unlimited. There are seven councilmen, each representing a separate ward.[20]

Mayors

| Name | Term of Office |

|---|---|

| John Hayward Glover | 1852 |

| Joshua Welch | 1853 |

| W. T. Winn | 1854 |

| I. N. Heggie | 1855 |

| N. B. Knight | 1856 |

| J. W. Robertson | 1857 |

| R. W. Joyner | 1858 |

| I. N. Heggie | 1859 |

| Samuel Lawrence | 1860–1861 |

| J. A. Tolleson | 1862 |

| W. T. Winn | 1863 |

| H. M. Hammett | 1864[lower-alpha 1] |

| C.C. Winn | 1865[lower-alpha 2] |

| A. N. Simpson | 1866–1868 |

| G. W. Cleland | 1869 |

| William H. Tucker | 1870–1873 |

| Humphrey Reid | 1874 |

| William H. Tucker | 1875 |

| Edward Denmead | 1876–1877 |

| Humphrey Reid | 1878 |

| Joel T. Haley | 1879 |

| Edward Denmead | 1880–1883 |

| Enoch Faw | 1884 |

| W. M. Sessions | 1885 |

| Edward Denmead | 1886–1887 |

| Thomas W. Glover | 1888–1893 |

| R. N. Holland | 1894–1895 |

| D. W. Blair | 1896–1897[lower-alpha 3] |

| W. M. Sessions | 1898–1899 |

| T. M. Brumby Sr. | 1900–1901 |

| Joe P. Legg | 1902–1903 |

| John E. Mozley | 1904–1905 |

| E. P. Dobbs | 1906–1909 |

| Eugene Herbert Clay | 1910–1911 |

| J. J. Black | 1912–1913 |

| E. P. Dobbs | 1914–1915 |

| James R. Brumby Jr. | 1916–1922[lower-alpha 4] |

| Gordon B. Gann | 1922–1925[lower-alpha 5] |

| E. R. Hunt | 1926–1927 |

| Gordon B. Gann | 1928–1929 |

| T. M. Brumby Jr. | 1930–1938[lower-alpha 6] |

| L. M. Blair | 1938–1947[lower-alpha 7] |

| Sam J. Welsch | 1948–1955 |

| C. W. Bramlett | 1956–1959 |

| Sam J. Welsch | 1960–1963 |

| L. H. Atherton Jr. | 1964–1969 |

| James R. Hunter | 1970–1973 |

| J. Dana Eastham | 1974–1981 |

| Robert E. Flournoy Jr. | 1982–1985 |

| Vicki Chastain | 1986–1989 |

| Joe Mack Wilson | 1990–1993[lower-alpha 8] |

| Ansley L. Meaders | 1993–2001[lower-alpha 9] |

| William B. Dunaway | 2002–2009 |

| Steve Tumlin | 2010–present |

- Hammett acted as Mayor until about July 1, 1864, at which time the city was invaded by the Federal Army and was occupied by them until November 15, when it was evacuated. In the meantime, a large portion of the city had been reduced to ashes.

- On reestablishing order, Winn was elected Mayor for 1865. He served until October 1, when he resigned. A. N. Simpson was elected to fill the vacancy.

- T. M. Brumby Sr. was elected for the 1898–1899 term, but he resigned before taking the oath of office. A special election was held on January 8, 1898.

- Resigned February 9, 1922.

- Took office March 9, 1922.

- Died, August 20, 1938.

- Term began September 7, 1938.

- Died May 17, 1993.

- Term began July 1, 1993.

Economy

Personal income

The median income for a household in the city was $40,645, and the median income for a family was $47,340. Males had a median income of $31,186 versus $30,027 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,409. About 11.5% of families and 15.7% of the population were below the poverty line. 21.3% of those under age 18 and 10.2% of those aged 65 or over.

Industry

Dobbins Air Reserve Base on the south side of town and a Lockheed Martin manufacturing plant are among the major industries in the city. The Lockheed Georgia Employees Credit Union is based in Marietta.[21]

Top employers

According to Marietta's 2010 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[22] the top employers within the city were:

| # | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cobb County School District | 13,371 |

| 2 | Lockheed Martin | 6,000 |

| 3 | WellStar Kennestone Hospital | 4,700 |

| 4 | YKK | 2,500 |

| 5 | Alere | 1,766 |

| 6 | Columbian Chemicals | 1,410 |

| 7 | C. W. Matthews Contracting Co. | 1,400 |

| 8 | Tip Top Poultry | 1,300 |

| 9 | U.S. Security Associates | 950 |

| 10 | Cobb County Government | 911 |

Infrastructure

Utilities

The city operates Marietta Power under the auspices of the Board of Lights & Water.

Roads

Interstate 75 and U.S. 41 run through the eastern part of the city. State routes 3, 5, and 120 also run through Marietta.

Transit systems

CobbLinc, Marietta/Cobb County's Transit System and Xpress GA Buses serve the City.

Rail

The CSX freight trains between Atlanta and Chattanooga (Western & Atlantic Subdivision) still run a block west of the town square, past the 1898-built former railroad depot (now the Visitor Center).[23]

Into the 1950s the Louisville and Nashville Railroad operated the Midwest-Florida trains, the Cincinnati-Florida Flamingo and the Chicago-Florida Southland, which made daily stops in Marietta Depot. Into the 1960s the L&N's Chicago & St. Louis-Florida trains, Dixie Flyer and Dixie Limited also made stops there. The final train was the L&N's St. Louis, MO - Evansville, IN - Atlanta Georgian which ended service on April 30, 1971. (Until 1968 the train also had a northern leg from Evansville to Chicago.)[24]

Media

The Marietta Daily Journal is published in the city.

Education

All of the public schools in Marietta proper are operated by the Marietta City Schools (MCS), while the remainder of the schools in Cobb County, but outside the city limits, is operated by the Cobb County School District, including all of the county's other cities. MCS has one high school, Marietta High School, grades 9-12; a middle school, Marietta Middle School, grades 7 and 8; Marietta Sixth Grade Academy; and several elementary schools: A.L. Burruss, Dunleith, Hickory Hills, Lockheed, Marietta Center for Advanced Academics, Park Street, Sawyer Road, and West Side.[25] Many residents of Marietta attend Cobb County public schools, such as Joseph Wheeler High School and Sprayberry High School. These schools are known to compete fiercely in athletics, especially basketball, as both Wheeler and Marietta High School frequently produce D-1 players. The town of Marietta is also home to the Walker School, a private pre-kindergarten through 12th-grade school. Walker competes in the Georgia High School Association Class A (Region 6) athletic division while Marietta and Wheeler compete in Class AAAAAA (Regions 4 and 5, respectively).

The school system employs 1,200 people. MCS is an International Baccalaureate (IB) World School district. In 2008, MCS became only the second IB World School district in Georgia authorized to offer the IB Middle Years Program (MYP) for grades 6-10. MCS is one of only a few school systems nationwide able to provide the full IB (K-12) continuum.[26]

Kennesaw State University (Marietta Campus) formally Southern Polytechnic State University (SPSU), and Life University are located in Marietta, serving more than 20,000 students in more than 90 programs of study.

Culture

The city has six historic districts, some on the National Register of Historic Places (these include Northwest Marietta, Whitlock Avenue, Washington Avenue, and Church-Cherokee Streets).[27] The city's welcome center is located in the historic train depot.

Downtown is the town square and former location of the county courthouse. The square is the site of several cultural productions and public events, including a weekly farmers' market.

The Marietta Players perform semi-professional theater year-round. The historic Strand Theatre has been renovated back to its original design and features live theatre, concerts, classic films, and other events.[14] The Marietta/Cobb Museum of Art is in the old Post Office building.

The Marietta Museum of History exhibits the history of the city and county. The museum is home to thousands of artifacts including items from Marietta residents and businesses. The Marietta Gone with the Wind Museum, also called "Scarlett on the Square", houses a collection of memorabilia related to Gone with the Wind, both the book and the film.[14] The William Root House Museum and Garden is the oldest wood-frame house still standing in Marietta, built circa 1845. Once owned by William Root, one of Marietta's founding citizens and merchants whose drugstore was located in the Square.[28]

The Big Chicken is a landmark on U.S. 41.

Miramax Films and Disney filmed scenes of the 1995 movie Gordy here. The 2014 film Dumb and Dumber To filmed a scene in the Marietta Square.[29]

The city includes the Kennesaw House, one of only four buildings in Marietta not burned to the ground in Sherman's March to the Sea. The Kennesaw House is home to the Marietta Museum of History[30] which tells the history of Marietta and Cobb County.

Notable people

- Murray Attaway, singer/songwriter, founding member of Guadalcanal Diary

- Big Boss Man, professional wrestler, inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2016

- Alton Brown, Good Eats

- Marcus Alexander Bagwell, professional wrestler, formerly with the World Wrestling Federation, World Championship Wrestling, & Total Nonstop Action Wrestling

- Alan Ball, Academy Award-winning screenwriter

- Chris Beard, Texas Tech men's basketball coach

- Alice Birney (1858–1907), co-founder of National Parent-Teacher Association, born in Marietta[31]

- Billy Burns, current Major League Baseball player

- Jaylen Brown, NBA player for Boston Celtics

- Marlon Byrd, former Major League Baseball player

- K Camp, Rapper[32]

- Lucius D. Clay, General, US Army, Military Governor of Germany post-WWII

- Jonathan Dwyer, former NFL player

- Frank Freyer, 14th Naval Governor of Guam and Chief of Staff of Peruvian Navy[33]

- George H. Gay Jr., sole survivor of Torpedo Squadron 8 at Battle of Midway[34]

- Cedric Henderson, NBA player for Atlanta Hawks and Milwaukee Bucks[35]

- Richard Howell (born 1990), basketball player for Hapoel Tel Aviv of Israeli Basketball Premier League[36]

- Marvin Hudson, Major League Baseball umpire

- Lucy McBath, activist and US Representative

- Adam Morgan, MLB player for Philadelphia Phillies

- Jim Nash, former MLB player[37]

- Melanie Oudin, professional tennis player, US Open 2009 quarterfinalist[38]

- Jennifer Paige, singer[39]

- Lennon Parham, actress and comedian

- Robert Patrick, actor

- Ron Pope, singer/songwriter

- Mathew Pitsch, Republican member of the Arkansas House of Representatives from Fort Smith since 2015; former resident of Marietta[40]

- Marco Restrepo, musician[41]

- Billy Joe Royal, singer

- Chris Robinson, former Black Crowes singer

- Rich Robinson, former Black Crowes guitar player

- Cody Rhodes (Cody Runnels), professional wrestler[42]

- Lawson Vaughn, MLS professional soccer player

- Daniela Silivaș-Harper, Romanian gymnast and coach

- Ron Simmons, professional wrestler, member of WWE Hall of Fame and College Football Hall of Fame

- Dansby Swanson, Major League Baseball player for Atlanta Braves, first overall pick in 2015 MLB Draft

- Emily Sonnett, professional soccer player for the U.S. women's national soccer team and Portland Thorns FC

- Luke Thomas, MMA journalist, lived for two years in Marietta and graduated from Marietta High School[43]

- Travis Tritt, country music singer and composer

- Lynn Turner, Convicted murderer

- Jeff Walls, guitarist, songwriter, founding member of Guadalcanal Diary

- Isadora Williams, American-Brazilian figure skater who represented Brazil at 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi[44]

- Michael Len Williams II (Mike Will Made It), record producer[45]

- Xavier Woods, (Austin Watson), professional wrestler, YouTube personality

- Joanne Woodward, Actress and married to Paul Newman.

- Jabari Zuniga, NFL player for the New York Jets.

Sister cities

Marietta has two sister cities.[46]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Marietta city, Georgia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- "City Data: Marietta (GA)". City Data.

- "Marietta | Georgia.gov". Marietta.georgia.gov. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Oakton House". Oaktonhouseandgardens.com. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- History of Oakton retrieved May 1, 2008

- "On this date in Civil War history: The Great Locomotive Chase – April 12, 1862". Thiswekinthecivilwar.com. April 13, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- "About Marietta Confederate Cemetery". Marietta Confederate Cemetery Foundation and Friends of Brown Park, Inc. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- Kirby, Joe; Guarnieri, Damien A. (2009). Marietta Revisited. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 49–53. ISBN 978-0-7385-6634-4.

- Oney, Steve (2003). And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank. New York: Random House. pp. 513-521. Dinnerstein, Leonard. The Leo Frank Case. University of Georgia Press, 1987. pp. 139-140. content_id=6631399 "POLITICS, PREJUDICE, AND PERJURY" p. 9 (March 1, 2000).

- PRISM Climate Group Oregon State University, Agricultural Research Center. "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". USDA. USDA. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- "Monthly Averages for Marietta, GA". weather.com. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Marietta: History". City-Data.com. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- "City Council". Mariettaga.gov. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- "Who We Are". LGE Community Credit Union. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- "City of Marietta CAFR" (PDF). Mariettaga.gov. p. 157. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- Marietta Depot https://railga.com/Depots/marietta.html

- American Rails, The Georgian https://www.american-rails.com/georgian.html

- "Marietta City Schools: School Listing". Marietta-city.org. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- "Marietta City Schools: About Us: Fact Sheet". Marietta-city.org. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- "Historic Districts". City of Marietta Georgia. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- http://www.roothousemuseum.com

- Kory, Melissa (October 10, 2013). ""Dumb and Dumber To" to Film in Marietta Square". Marietta Patch. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- "Marietta Museum of History » Your Hometown History Hotspot!". Mariettahistory.org. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- Elvena B. Tillman, "Alice Josephine McLellan Birney," in Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, eds., Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary (Harvard University Press 1971): 147-148. ISBN 0674627342

- Jones, Danitha (April 8, 2016). "K Camp Shares Stories About His Upbringing, Atlanta's Music Scene, And More". The Stashed. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- "Initiates for the College Year 1895–96". Caduceus of Kappa Sigma. Charlottesville, Virginia: Kappa Sigma. 11: 388. 1896. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- "George H. Gay, 77; Was Sole Survivor In a Midway Attack". Nytimes.com. October 24, 1994. Retrieved August 27, 2017 – via NYTimes.com.

- "Cedric Henderson Past Stats, Playoff Stats, Statistics, History, and Awards". Basketballreference.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- Archived August 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Smith, Red "Nash Could Fit Into Met Mold". Philadelphia Inquirer. April 2, 1967. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- "WTA | Players | Info | Melanie Oudin". Sonyericssonwtatour.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2009. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- Whitburn, Joel (2004). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits (8th ed.). New York: Billboard Books. p. 478. ISBN 0-8230-7499-4.

Born on 9/3/75 in Marietta, Georgia. Pop singer.

- "Mathew W. Pitsch". intelius.com. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Rhodes, Cyrus. "Marco Restrepo". RockNRollView.com. Blackwell. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- "Cody Rhodes". Accelerator3359.com. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fT5XT7fD1U8#t=57m3s

- "Isadora Williams puts Brazil on Olympic skating map". February 26, 2014. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- Noz, Andrew (April 30, 2012). "Beat Construction: Mike WiLL Made It". The Fader.

- "Online Directory: Georgia, USA". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on April 18, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

Further reading

At least two books have been produced chronicling the history of the city in pictures:

- Marietta Then and Now series. ISBN 978-0-7385-5314-6

- Marietta Revisited Then and Now series. (ISBN 978-0-7385-6634-4)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Marietta (Georgia). |