History of the Jews in Canada

The history of the Jews in Canada is the history of Canadian citizens who follow Judaism as their religion and/or are ethnically Jewish. Jewish Canadians are a part of the greater Jewish diaspora and form the fourth largest Jewish community in the world, exceeded only by those in Israel, the United States, and France.[5][6] As of 2011, Statistics Canada listed 329,500 adherents to the Jewish religion in Canada[7] and 309,650 who claimed Jewish as an ethnicity.[8] One does not necessarily include the other and studies which have attempted to combine the two streams have arrived at figures in excess of 375,000 Jews in Canada.[2][3][4] This total would account for approximately 1.1% of the Canadian population.

Canadian and American Jews as % of population by region | |

| Total population | |

1.1% of the Canadian population[2][3][4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 227,000 | |

| 94,000 | |

| 35,000 | |

| 14,000 | |

| 16,000 | |

| Languages | |

| English (among Ashkenazim) · French (among Sephardim and Québécois) · Hebrew (as liturgical language, some as mother tongue) · Yiddish (by some as mother tongue and as part of a language revival) · and other languages like Russian, Ukrainian, Lithuanian, Polish, German and Marathi | |

| Religion | |

| Mostly Judaism and Jewish secularism | |

The Jewish community in Canada is composed predominantly of Ashkenazi Jews and their descendants. Other Jewish ethnic divisions are also represented and include Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, and Bene Israel. A number of converts to Judaism make up the Jewish-Canadian community, which manifests a wide range of Jewish cultural traditions and encompasses the full spectrum of Jewish religious observance. Though they are a small minority, they have had an open presence in the country since the first Jewish immigrants arrived with Governor Edward Cornwallis to establish Halifax, Nova Scotia (1749).[9]

Early history (1759–1850)

Prior to the British Conquest of New France, there were Jews in Nova Scotia. There were no official Jews in Quebec because when King Louis XIV made Canada officially a province of the Kingdom of France in 1663, he decreed that only Roman Catholics could enter the colony. One exception was Esther Brandeau, a Jewish girl who arrived in 1738 disguised as a boy and remained for a year before being sent back to France after refusing to convert.[10] The earliest subsequent documentation of Jews in Canada are British Army records from the French and Indian War, the North American part of the Seven Years' War. In 1760, General Jeffrey Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst attacked and seized Montreal, winning Canada for the British. Several Jews were members of his regiments, and among his officer corps were five Jews: Samuel Jacobs, Emmanuel de Cordova, Aaron Hart, Hananiel Garcia, and Isaac Miramer.[11]

The most prominent of these five were the business associates Samuel Jacobs and Aaron Hart. In 1759, in his capacity as Commissariat to the British Army on the staff of General Sir Frederick Haldimand, Jacobs was recorded as the first Jewish resident of Quebec, and thus the first Canadian Jew.[12] From 1749, Jacobs had been supplying British army officers at Halifax, Nova Scotia. In 1758, he was at Fort Cumberland and the following year he was with Wolfe's army at Quebec.[13] Remaining in Canada, he afterwards became the dominant merchant of the Richelieu valley and Seigneur of Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu.[14] However, as Jacobs married a French Canadian girl and brought his children up as Catholics, he is often overlooked as the first permanent Jewish settler in Canada in favour of Aaron Hart, who married a Jew and brought up his children, or at least his sons, in the Jewish tradition.[13]

Lieutenant Hart first arrived in Canada from New York City as Commissariat to Jeffery Amherst's forces at Montreal in 1760. After his service in the army had ended, he settled at Trois-Rivières. Eventually, he became a very wealthy landowner and a respected community member. He had four sons, Moses, Benjamin, Ezekiel and Alexander, all of whom would become prominent in Montreal and help build the Jewish Community. One of his sons, Ezekiel, was elected to the legislature of Lower Canada in the by-election of April 11, 1807, becoming the first Jew in an official opposition in the British Empire. Ezekiel was expelled from the legislature with his religion a major factor.[15] Sir James Henry Craig, Governor-General of Lower Canada, tried to protect Hart, but the legislature dismissed him in both 1808 and 1809. French Canadians later saw this as an attempt of the British to undermine their role in Canada. Ezekiel was re-elected to the legislature, but Jews were not allowed to hold elected office in Canada until a generation later.

Most of the early Jewish Canadians were either fur traders or served in the British Army troops. A few were merchants or landowners. Although Montreal's Jewish community was small, numbering only around 200, they built the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue of Montreal, Shearith Israel, the oldest synagogue in Canada in 1768. It remained the only synagogue in Montreal until 1846.[16] Some sources date the actual establishment of synagogue to 1777 on Notre Dame Street.[17]

Revolts and protests soon began calling for responsible government in Canada. The law requiring the oath "on my faith as a Christian" was amended in 1829 to provide for Jews to not take the oath. In 1831, prominent French-Canadian politician Louis-Joseph Papineau sponsored a law which granted full equivalent political rights to Jews, twenty-seven years before anywhere else in the British Empire. In 1832, partly because of the work of Ezekiel Hart, a law was passed that guaranteed Jews the same political rights and freedoms as Christians. In the early 1830s, German Jew Samuel Liebshitz founded Jewsburg (now incorporated as German Mills into Kitchener, Ontario), a village in Upper Canada.[18] By 1850, there were still only 450 Jews living in Canada, mostly concentrated in Montreal.[19]

Abraham Jacob Franks settled at Quebec City in 1767.[20] His son, David Salesby (or Salisbury) Franks, who afterward became head of the Montreal Jewish community, also lived in Quebec prior to 1774. Abraham Joseph, who was long a prominent figure in public affairs in Quebec City, took up his residence there shortly after his father's death in 1832. Quebec City's Jewish population for many years remained very small, and early efforts at organization were fitful and short-lived. A cemetery was acquired in 1853, and a place of worship was opened in a hall in the same year, in which services were held intermittently; but it was not until 1892 that the Jewish population of Quebec City had sufficiently augmented to permit of the permanent establishment of the present synagogue, Beth Israel. The congregation was granted the right of keeping a register in 1897. Other communal institutions were the Quebec Hebrew Sick Benefit Association, the Quebec Hebrew Relief Association for Immigrants, and the Quebec Zionist Society. By 1905, the Jewish population was about 350, in a total population of 68,834.[21] According to census of 1871, there were 1, 115 Jews living in Canada with 409 in Montreal, 157 in Toronto, and 131 in Hamilton with the rest living in Brantford, Quebec City, St. John, Kingdon and London.[19]

Growth of the Canadian Jewish community (1850–1939)

With the beginning of the pogroms of Russia in the 1880s, and continuing through the growing anti-Semitism of the early 20th century, millions of Jews began to flee the Pale of Settlement and other areas of Eastern Europe for the West. Although the United States received the overwhelming majority of these immigrants, Canada was also a destination of choice due to Government of Canada and Canadian Pacific Railway efforts to develop Canada after Confederation. Between 1880 and 1930, the Jewish population of Canada grew to over 155,000. At the time, according to the 1901 census of Montreal, only 6861 Jews were residents.[22]

Jewish immigrants brought a tradition of establishing a communal body, called a kehilla to look after the social and welfare needs of their less fortunate. Virtually all of these Jewish refugees were very poor. Wealthy Jewish philanthropists, who had come to Canada much earlier, felt it was their social responsibility to help their fellow Jews get established in this new country. One such man was Abraham de Sola, who founded the Hebrew Philanthropic Society. In Montreal and Toronto, there developed a wide range of communal organizations and groups. Recently arrived immigrant Jews also founded landsmenschaften, guilds of people who came originally from the same village.

Most of these immigrants established communities in the larger cities. Canada's first ever census, recorded that in 1871 there were 1,115 Jews in Canada; 409 in Montreal, 157 in Toronto, 131 in Hamilton and the rest were dispersed in small communities along the St. Lawrence River.[19] When elected mayor of Alexandria in 1914, George Simon had the double honour of being both the first Jewish mayor in Canada, as well as the youngest mayor in the country at the time. He died suddenly in 1969 while serving his tenth term in office.[23]

A community of about 100 settled in Victoria, British Columbia to open shops to supply prospectors during the Cariboo Gold Rush (and later the Klondike Gold Rush in the Yukon). This led to the opening of a synagogue in Victoria, British Columbia in 1862. In 1875, B'nai B'rith Canada was formed as a Jewish fraternal organization. When British Columbia sent their delegation to Ottawa to agree on the colony's entry into Confederation, a Jew, Henry Nathan, Jr., was among them. Nathan eventually became the first Canadian Jewish Member of Parliament. In 1899, the Federation of Canadian Zionist Societies was founded to champion Zionism, and became the first nation-wide Jewish group.[19] The overwhelming majority of Canadian Jews were Ashkenazim who came from either the Austrian empire or the Russian empire.[19] Jewish women tended to be particularly active in Canadian Zionism, perhaps because many of the Zionist groups were secular.[19]

By 1911, there were Jewish communities in all of Canada's major cities. By 1914, there were about 100, 000 Jews in Canada with three quarters living in either Montreal or Toronto.[19] The overwhelming majority of Canadian Jews were Ashkenazim who came from either the Austrian empire or the Russian empire.[19] There were two competing strands of Jewish nationalism in Eastern Europe in the early 20th century, namely Zionism and another tendency that favored forming separate Jewish cultural institutions with a focus on promoting Yiddish.[19] Institutions such as the Montreal Jewish Library with its collection of Yiddish books were examples of the latter tendency.[19]

Benjamin Hart, businessman, militia officer, and justice of the peace, 1855

Benjamin Hart, businessman, militia officer, and justice of the peace, 1855 The Ward, Toronto, a predominantly Jewish neighbourhood, 1910

The Ward, Toronto, a predominantly Jewish neighbourhood, 1910 Jewish rag picker, Bloor Street West, Toronto, 1911

Jewish rag picker, Bloor Street West, Toronto, 1911 Dedication of the new Synagogue, Kirkland Lake, Ontario. Rabbi Joseph Rabin carrying the Torah, 1929

Dedication of the new Synagogue, Kirkland Lake, Ontario. Rabbi Joseph Rabin carrying the Torah, 1929.jpg) The Canadian Jewish Farm School in Georgetown, Ontario was established in 1927 and served as a training school for Polish war orphans brought to Canada after the First World War[24]

The Canadian Jewish Farm School in Georgetown, Ontario was established in 1927 and served as a training school for Polish war orphans brought to Canada after the First World War[24]

The Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) was founded in 1919 and would be the major representative body of the Canadian Jewish community for 90 years. Much of its work was focused on lobbying government around issues of immigration, human rights and anti-Semitism. One of the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles were the so-called "minorities treaties" that committed Eastern European states with substantial Jewish populations such as Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia to protect the rights of minorities with the League of Nations to monitor their compliance. The CJC was founded in part to lobby the government of Canada to use its influence at the League of Nations to ensure that the Eastern European states were abiding by the terms of the "minorities treaties".[19] Jewish total population in Canada was 1.8%.

On August 6, 1933 one of the most famous anti-Semitic incidents in Canada took place, known as "the Christie Pits Riot". On that day after a baseball game in Toronto a group of young men using Nazi symbols started a massive melee, arguably the largest in Toronto's history, on the ground of racial hatred, involving hundreds of men.[25]

Jewish settlement in the West

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, through such utopian movements as the Jewish Colonization Association, fifteen Jewish farm colonies were established on the Canadian prairies;[26] However, few of the colonies did very well. This was partly because, the Jews of East European origin were not allowed to own farms in the old country, and thus had little experience in farming. One settlement that did do well was Yid'n Bridge, Saskatchewan, started by South African farmers. Eventually the community grew larger as the South African Jews, who had gone to South Africa from Lithuania invited Jewish families directly from Europe to join them, and the settlement eventually became a town, whose name was later changed to the Anglicized name of Edenbridge.,[26][27][28] The Jewish farming settlement did not last to a second generation, however.[26] Beth Israel Synagogue at Edenbridge is now a designated heritage site. In Alberta, the Little Synagogue on the Prairie is now in the collection of a museum.

At this time, most of the Jewish Canadians in the west were either storekeepers or tradesmen. Many set up shops on the new rail lines, selling goods and supplies to the construction workers, many of whom were also Jewish. Later, because of the railway, some of these homesteads grew into prosperous towns. At this time, Canadian Jews also had important roles in developing the west coast fishing industry, while others worked on building telegraph lines. Some, descended from the earliest Canadian Jews, stayed true to their ancestors as fur trappers. The first major Jewish organization to appear was B'nai B'rith. Till today B'nai B'rith Canada is the community's independent advocacy and social service organization. Also at this time, the Montreal branch of the Workmen's Circle was founded in 1907. This group was an offshoot of the Jewish Labour Bund, an outlawed party in Russia's Pale of Settlement. It was an organization for The Main's radical, non-Communist, non-religious, working class.[29]

Growth and community organization

By the outbreak of World War I, there were approximately 100,000 Canadian Jews, of whom three-quarters lived in either Montreal or Toronto. Many of the children of the European refugees started out as peddlers, eventually working their way up to established businesses, such as retailers and wholesalers. Jewish Canadians played an essential role in the development of the Canadian clothing and textile industry.[30] Most worked as labourers in sweatshops; while some owned the manufacturing facilities. Jewish merchants and labourers spread out from the cities to small towns, building synagogues, community centres and schools as they went.

As the population grew, Canadian Jews began to organize themselves as a community despite the presence of dozens of competing sects. The Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) was founded in 1919 as the result of the merger of several smaller organizations. The purpose of the CJC was to speak on behalf of the common interests of Jewish Canadians and assist immigrant Jews. The largest Jewish community was in Montreal, at the time the most largest, wealthiest and most cosmopolitan city in Canada.[31] The vast majority of Montreal's Jews who arrived in the early 20th century were Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim but their children chose speak English rather than French.[31] Until 1964, Quebec had no public education system, instead having two parallel educational systems run by the Protestant churches and the Catholic church. As the Jewish community did not have the financial resources to set up their own educational system, most Jewish parents chose to enroll their children in the English-speaking Protestant school system, which was willing to accept Jews unlike the Catholic school system.[31] The CJC had its headquarters in Montreal while the Jewish Public Library of Montreal and the Montreal Yiddish Theatre were two of the largest Jewish cultural institutions in Canada.[31] The Jews of Montreal tended to be concentrated in several neighborhoods, which gave a strong sense of community identity.[31]

In 1930 under the impact of the Great Depression, Canada sharply limited immigration from Eastern Europe, which adversely impacted on the ability of the Ashkenazim to come to Canada.[19] In a climate of anti-semitism where the Jewish immigrants were seen as economic competition for Gentiles, the leadership of the CJC was assumed by the whisky tycoon Samuel Bronfman who it was hoped might be able to persuade the government to allow more Jews to come.[19] In view of worsening situation for Jews in Europe, allowing more Jewish immigration became the central concern of the CJC.[19] Through many Canadian Jews voted for the Liberal Party, traditionally seen as the friend of minorities, the Liberal Prime Minister from 1935 onward, William Lyon Mackenzie King, proved to be extremely unsympathetic. Mackenzie King adamantly refused to change the immigration law, and Canada accepted proportionally the fewest Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany.[19]

World War II (1939–1945)

Almost 20,000 Jewish Canadians volunteered to fight for Canada during World War II. Major Ben Dunkelman of the Queen's Own Rifles regiment was a noted soldier in the campaigns of 1944-45 in north-west Europe, being highly decorated for his courage and ability under fire. In 1943, Saidye Rosner Bronfman of Montreal, the wife of the whiskey tycoon Samuel Bronfman was awarded a MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) for her work on the home front.[32] Saidye Bronfram had organized 7, 000 women in Montreal to make packages for Canadian soldiers serving overseas, for which she was recognized by King George VI.[32]

In 1939, Canada turned away the MS St. Louis with 908 Jewish refugees aboard. It went back to Europe where 254 of them died in concentration camps. And overall, Canada only accepted 5,000 Jewish refugees during the 1930s and 1940s in a climate of widespread anti-Semitism.[33] A most striking display of antisemitism occurred with the 1944 Quebec election. The leader of the Union Nationale, Maurice Duplessis appealed to anti-Semitic prejudices in Quebec in a violently anti-Semitic speech by claiming that the Dominion government of William Lyon Mackenzie King together with Liberal Premier Adélard Godbout of Quebec had secretly made an agreement with the "International Zionist Brotherhood" to settle 100,000 Jewish refugees left homeless by the Holocaust in Quebec after the war in exchange for the "International Zionist Brotherhood" promising to fund both the federal and provincial Liberal parties.[34] By contrast, Duplessis claimed that he would never take any money from the Jews, and if he were elected Premier, he would stop this alleged plan to bring Jewish refugees to Quebec. Though Duplessis' claims about the alleged plan to settle 100,000 Jewish refugees in Quebec was entirely false, his story was widely believed in Quebec, and ensured he won the election.[34]

In 1945, several organizations merged to form the left-wing United Jewish Peoples' Order which was one of the largest Jewish fraternal organizations in Canada for a number of years.[35][36]

As in the United States, the community's response to news of the Holocaust was muted for decades. Bialystok (2000) argues that in the 1950s the community was "virtually devoid" of discussion. Although one in seven Canadian Jews were survivors and their children, most Canadian Jews "did not want to know what happened, and few survivors had the courage to tell them.' He argues that the main obstacle to discussion was "an inability to comprehend the event. Awareness emerged in the 1960s, however, as the community realized that antisemitism had not disappeared.[37]

Post war (1945–1999)

From the 1940s to the 1960s, the man generally recognized as the chief spokesman for the Canadian Jewish community was Rabbi Abraham Feinberg of the Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto.[38] In 1950, Dorothy Sangster wrote in Macleans' about him: "Today American-born Rabbi Feinberg is one of the most controversial figures to occupy a Canadian pulpit. Gentiles recognize him as the official voice of Canadian Jewry. This fact was aptly demonstrated a few years ago when Montreal's Mayor Houde introduced him to friends as Le Cardinal des Juifs—the Cardinal of the Jews".[39] Feinberg was very active in various social justice efforts, campaigning for laws against discrimination against minorities and to end the "restrictive covenants".[38]

In March 1945, Rabbi Feinberg wrote an article in Maclean's charging that there was rampant antisemitism in Canada, stating:

"Jews are kept out of most ski clubs. Sundry summer colonies (even on municipally owned land), fraternities, and at least one Rotary Club operate under written or unwritten “Gentiles Only” signs. Many bank positions are not open to Jews. Only three Jewish male physicians have been admitted to non-Jewish Hospital staffs in Toronto. McGill University has instituted a rule requiring in effect at least a 10% higher academic average for Jewish applicants; in certain schools of the University of Toronto anti-Jewish bias is being felt. City Councils debate whether Jewish petitioners should be permitted to build a synagogue; property deeds in some areas bar resale to them. I have seen crude handbills circulated thanking Hitler for his massacre of 80,000 Jews in Kiev."[40]

In 1945, in the Re Drummond Wren case, a Jewish group, the Workers' Education Association (WEA) challenged the "restrictive covenants" that forbade the renting or selling of properties to Jews.[41] Through the case was something of a set-up as the WEA had quite consciously purchased a property in Toronto known to have a "restrictive covenant" in order to challenge the legality of "restrictive covenants" in the courts, Justice John Keiller MacKay struck down "restrictive covenants" in his ruling on 31 October 1945.[42] In 1948, MacKay's ruling in the Drummond Wren case was struck down in the Noble v Alley case by the Ontario Supreme Court, which ruled that "restrictive covenants" were "legal and enforceable".[43] A woman named Anna Noble decided to sell her cottage at the Beach O' Pines resort to Bernard Wolf, a Jewish businessman from London, Ontario. The sale was blocked by the Beach O'Pines Resort Association which had a "restrictive covenant" forbidding the sale of cottages to any person of "Jewish, Hebrew, Semitic, Negro or colored race or blood".[44] With the support of the Joint Public Relations Committee of the Canadian Jewish Congress and B'nai B'rith headed by Rabbi Feinberg, the Noble ruling was appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, which in November 1950 ruled against "restrictive covenants", albeit only on the technicality that the phrase "Jewish, Hebrew, Semitic, Negro or colored race or blood" was too vague.[45]

After the war, Canada liberalized its immigration policy. Roughly 40,000 Holocaust survivors came during the late 1940s, hoping to rebuild their shattered lives. In 1947, the Workmen's Circle and Jewish Labour Committee started a project, spearheaded by Kalmen Kaplansky and Moshe Lewis, to bring Jewish refugees to Montreal in the needle trades, called the Tailors Project.[46] They were able to do this through the federal government's "bulk-labour" program that allowed labour-intensive industries to bring European displaced persons to Canada, in order to fill those jobs.[47] For Lewis' work on this and other projects during this period, the Montreal branch was renamed the Moshe Lewis Branch, after his death in 1950. The Canadian arm of the Jewish Labor Committee also honored him when they established the Moshe Lewis Foundation in 1975.[48]

In the post-war era, universities proved more willing to accept Jewish applicants and in decades after 1945, many Canadian Jews tended to move up from being a lower-class group working as menial laborers to a middle class group working as bourgeois professionals.[19] With the ability to obtain a better education, many Jews become doctors, teachers, lawyers, dentists, accountants, professors and other bourgeois occupations.[19] Geographically, there was a tendency for many Jews living in the inner cities of Toronto and Montreal to move out to the suburbs.[19] The rural Jewish communities almost vanished as Jews living in rural areas decamped to the cites.[19] Reflecting a more tolerant attitude, Canadian Jews became active on the cultural scene.[19] In the post-war decades Peter C. Newman, Wayne and Shuster, Mordecai Richler, Leonard Cohen, Barbara Frum, Joseph Rosenblatt, Irving Layton, Eli Mandel, A.M. Klein, Henry Kreisel, Adele Wiseman, Miriam Waddington, Naim Kattan, and Rabbi Stuart Rosenberg were individuals of note in the fields of arts, journalism and literature.[19]

Since the 1960s a new immigration wave of Jews started to take place. A number of French-speaking Jews from North Africa ended up settling in Montreal.[19] Some South African Jews decided to emigrate to Canada after South Africa became a republic in 1961, and was followed by another wave in the late 1970s, which was precipitated by anti-apartheid rioting and civil unrest.[49] The majority of them settled in Ontario, with the largest community in Toronto, followed by those in Hamilton, London and Kingston. Smaller waves of Zimbabwean Jews were also present during this period.

In 1961 Louis Rasminsky became the first Jewish governor of the Bank of Canada. Every previous governor of the Bank of Canada had been a member of the prestigious Rideau Club of Ottawa, but Rasminsky's application to join the Rideau Club was turned down on the account of his religion, a rejection that deeply hurt him.[50] Through the Rideau Club changed its policies in response to public criticism, Rasminsky only joined the club after he retired as bank governor in 1973.[50] In 1968, the Liberal MP Herb Gray of Windsor became the Jewish federal cabinet minister. In 1970, Bora Laskin became the first Jewish justice of the Supreme Court of Canada and in 1973, the first Jewish Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. In 1971, David Lewis became the leader of the New Democratic Party, becoming the first Jew to head a major Canadian political party.

In 1976, the Quebec provincial election was won by the separatist Parti Québécois (PQ), which sparked a major flight of Montreal's English-speaking Jews to Toronto with about 20, 000 leaving.[31] The Jewish community of Montreal has been a bastion of federalism, and Quebec separatists with their ideal of a creating a nation-state for French-Canadians have tended to be hostile towards Jews.[31] In both the 1980 and 1995 referendums, Montreal's Jews voted overwhelmingly for Quebec to remain in Canada.[31]

It was official Canadian policy after 1945 to accept immigrants from Eastern Europe as long they were anti-communist even if they had fought for Nazi Germany. For an example the veterans of the 14th Waffen SS Division Galizien, which was mostly recruited from Ukrainians in Galicia, settled in Canada.[51] The fact that the men of the 14th Waffen-SS division had committed war crimes was ignored because they were felt to be useful for the Cold War.[52] In Oakville, Ontario, a public monument honors the men of the 14th SS Division as heroes.[53] Starting in the 1980s, Jewish groups began to lobby the Canadian government to deport the Axis collaborators from Eastern Europe whom the government of Canada had welcomed with open arms in the 1940s-1950s.[19] In 1997, a report by Sol Littman, the head of Simon Wiesenthal Center operations in Canada charged that Canada in 1950 had accepted 2,000 veterans of 14th Waffen-SS Division with no screening; the American news program 60 Minutes showed that Canada had allowed about 1,000 SS veterans from the Baltic states to become Canadian citizens; and the Jerusalem Post called Canada a "near-blissful refuge" for Nazi war criminals.[54] The Canadian Jewish historian Irving Abella stated that for Eastern Europeans the best way of getting into postwar Canada "was by showing the SS tattoo. This proved that you were an anti-Communist".[54] Despite pressure from Jewish groups, the Canadian government dragged its feet on deporting Nazi war criminals out of the fear of offending voters of Eastern European background, who make up a significant number of Canadian voters.[54]

Canadian Jews today

Today the Jewish culture in Canada is maintained by both practising Jews and those who choose not to practise the religion (Secular Jews). Nearly all Jews in Canada speak one of the two official languages, although most speak English over French. However, there seems to be a sharp division between the Ashkenazi and the Sephardi community in Quebec.[55] The Ashkenazi overwhelmingly speak English while the Sephardi mostly speak French. There is also an increasing large number who speak Hebrew, other than for religious ceremonies, while a few keep the Yiddish language alive.

Recent surveys of the national Jewish population are unavailable. According to population studies of Toronto and Montreal, 14% and 22% are Orthodox, 37% and 30% are Conservative and 19% and 5% are Reform. The Reform movement is weaker in Canada, especially in Quebec, compared to the United States. This may explain the higher proportion of Canadian Jews who identify as unaffiliated – 30% in Montreal and 28% in Vancouver – than is the case in the United States. As in the United States, regular synagogue attendance is rather low – with less than one-quarter attending synagogue once a month or more.[56] However, Canadian Jews also seem to have lower intermarriage rates than the American Jewish community. Canadian census data should be reviewed with care, because it contains separate categories for religion and for ethnicity. Some Canadians identify themselves as ethnically but not religiously Jewish.

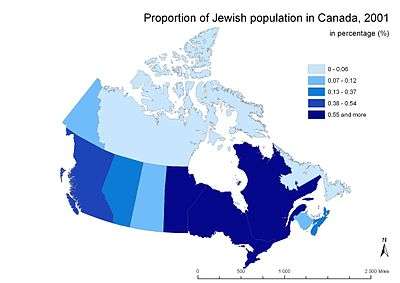

Most of Canada's Jews live in Ontario and Quebec, followed by British Columbia, Manitoba and Alberta. While Toronto is the largest Jewish population centre, Montreal played this role until many English-speaking Jewish Canadians left for Toronto, fearing that Quebec might leave the federation following the rise during the 1970s of nationalist political parties in Quebec, as well as a result of Quebec's Language Law. According to the 2001 census, 164,510 Jews lived in Toronto, 88,765 in Montreal, 17,270 in Vancouver, 12,760 in Winnipeg, 11,325 in Ottawa, 6,530 in Calgary, 3,980 in Edmonton, and 3,855 in Hamilton.[57]

.jpg) Ben's Deli was a Montreal icon during the 20th century

Ben's Deli was a Montreal icon during the 20th century

Association of Jewish Seniors/Canadian Jewish Political Affairs Committee hosting a Toronto Mayoral candidates' debate, 2010

Association of Jewish Seniors/Canadian Jewish Political Affairs Committee hosting a Toronto Mayoral candidates' debate, 2010 Schwartz's Hebrew Delicatessen, a popular deli in Montreal

Schwartz's Hebrew Delicatessen, a popular deli in Montreal Jewish members of Toronto Pride 2009 Parade for LGBT pride

Jewish members of Toronto Pride 2009 Parade for LGBT pride

The Jewish population is growing rather slowly due to aging and low birth rates. The population of Canadian Jews increased by just 3.5% between 1991 and 2001, despite much immigration from the Former Soviet Union, Israel and other countries.[58] Recently, anti-Semitism has become a growing concern, with reports of anti-semitic incidents increasing sharply in recent years. This includes the well publicized anti-Semitic comments by David Ahenakew and Ernst Zündel. In 2009, the Canadian Parliamentary Coalition to Combat Antisemitism was established by all four major federal political parties to investigate and combat antisemitism, namely new antisemitism.[59] However, anti-semitism is less of a concern in Canada than it is in most countries with significant Jewish populations. The League for Human Rights of B'nai B'rith monitors the incidents and prepares an annual audit of these events.

Politically, the major Jewish Canadian organizations are the Centre for Israel and Jewish Advocacy (CIJA) and the more conservative B'nai Brith Canada which both claim to be the voice of the Jewish community. The United Jewish People's Order, once the largest Jewish fraternal organization in Canada, is a left-leaning secular group established in 1927 with current chapters in Toronto, Hamilton, Winnipeg and Vancouver. Politically, UJPO opposes the Israeli Occupation and advocate for a two-state solution but focus primarily on Jewish cultural, educational and social justice issues. A smaller organization, Independent Jewish Voices (Canada), characterized as anti-Zionist, argues that the CIJA and B'nai B'rith do not speak for most Canadian Jews. Also, many Canadian Jews simply have no connections to any of these organizations.

Mainstream Jewish community views are expressed in Canadian Jewish News, a moderate weekly. Western Canadian Jewish views are reflected in the Winnipeg-based weekly The Jewish Post & News, as well as the Winnipeg Jewish Review.

The birth rate for Jews in Canada is much higher than that in the United States, with a TFR of 1.91 according to the 2001 Census. This is due to the presence of large numbers of orthodox Jews in Canada.[60] According to the census, the Jewish birth rate and TFR is higher than that of the Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox (1.35), Buddhist (1.34), Non-Religious (1.41), and Sikhs (1.9). populations, but slightly lower than that of Hindus (2.05), and Muslims (2.01).

In the 21st century there was an increase of the scope of anti-Semitic incidents in Canada with number of cases of anti-Semitic vandalism and spraying Nazi symbols in August 2013 in Winnipeg and in the greater Toronto area.[61][62]

On February 26, 2014, and for the first time in Canadian history, B'nai Brith Canada led an official delegation of Sephardi community leaders, activists, philanthropists and spiritual leaders from across the country visiting Parliament Hill and meeting with the prime minister, ambassadors and other dignitaries.[63]

Since the beginning of the 21st century Jewish immigration to Canada has continued, increasing in numbers with the passing of the years. With the rise of antisemitic acts in France and weak economic conditions, most of the Jewish newcomers are French Jews who are mainly looking for new economic opportunities (either in Israel or elsewhere, with Canada being one of the top destinations chosen by French Jews to live in, particularly in Quebec).[64] For the same reasons, and due to cultural and linguistic proximity, several members of the Belgian-Jewish community choose Canada as their new home. There are efforts by the Jewish community of Montreal to attract these immigrants and make them feel at home, not only from Belgium and France but from other parts of Europe and the world.[65] There is also some immigration of Argentine Jews and from other parts of Latin America with Argentina being home to the largest Jewish community in Latin America and the third one in the Americas after the United States and Canada itself.[66] However, the weight of French Jewish emigration must be balanced, as it represents between 2,000 and 3,000 people in total per year (Vs a community of ~500,000 people in France) and only a percentage of this couple of thousands go to Canada.

Also, there is a vibrant population of Israeli Jews who emigrate to Canada to study and work. The Israeli Canadian community is growing and it is one of the largest Israeli diaspora groups with an estimate of 30,000 people.[66] A small proportion of Israeli Jews who come to Canada are Ethiopian Jews.

Demographics

Jewish Canadians by province or territory

Jewish Canadian population by province and territory in Canada in 2011 according to Statistics Canada and United Jewish Federations of Canada[67]

| Province or territory | Jews | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 391,665 | 1.2% | |

| 226,610 | 1.8% | |

| 93,625 | 1.2% | |

| 35,005 | 0.8% | |

| 15,795 | 0.4% | |

| 14,345 | 1.2% | |

| 2,910 | 0.3% | |

| 1,905 | 0.2% | |

| 860 | 0.1% | |

| 220 | 0.0% | |

| 185 | 0.1% | |

| 145 | 0.4% | |

| 40 | 0.1% | |

| 15 | 0.1% |

Jewish Canadians by city

| 2001[68] | 2011[69] | Trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Population | Jews | Percentage | Population | Jews | Percentage | |

| Greater Toronto Area | 5,081,826 | 179,100 | 3.5% | 6,054,191 | 188,710 | 3.1% | |

| Greater Montreal | 3,380,645 | 92,975 | 2.8% | 3,824,221 | 90,780 | 2.4% | |

| Greater Vancouver | 1,967,480 | 22,590 | 1.1% | 2,313,328 | 26,255 | 1.1% | |

| Calgary | 943,315 | 7,950 | 0.8% | 1,096,833 | 8,335 | 0.8% | |

| Ottawa | 795,250 | 13,130 | 1.7% | 883,390 | 14,010 | 1.6% | |

| Edmonton | 666,105 | 4,920 | 0.7% | 812,201 | 5,550 | 0.7% | |

| Winnipeg | 619,540 | 14,760 | 2.4% | 663,617 | 13,690 | 2.0% | |

| Hamilton | 490,270 | 4,675 | 1.0% | 519,949 | 5,110 | 1.0% | |

| Kitchener-Waterloo | 495,845 | 1,950 | 0.4% | 507,096 | 2,015 | 0.4% | |

| Halifax | 355,945 | 1,985 | 0.6% | 390,096 | 2,120 | 0.5% | |

| London | 336,539 | 2,290 | 0.7% | 366,151 | 2,675 | 0.7% | |

| Victoria | 74,125 | 2,595 | 3.5% | 80,017 | 2,740 | 3.4% | |

| Windsor | 208,402 | 1,525 | 0.7% | 210,891 | 1,515 | 0.7% | |

Jewish culture in Canada

Languages

Hebrew

Hebrew (עברית) is the liturgical and historical language of the Jews and Judaism and also the language of Jewish Israeli expatriates living in Canada.

Yiddish

Yiddish (יידיש) is the historical and cultural language of Ashkenazi Jews, who make up the majority of the Canadian Jewry and was widely spoken within the Canadian Jewish community up to the middle of the twentieth century.

Montreal had and to some extent still has one of the most thriving Yiddish communities in North America. Yiddish was Montreal's third language (after French and English) for the entire first half of the 20th century. Der Kanader Adler ("The Canadian Eagle", founded by Hirsch Wolofsky), Montreal's daily Yiddish newspaper, appeared from 1907 to 1988.[70] The Monument National was the centre of Yiddish theatre from 1896 until the construction of the Saidye Bronfman Centre for the Arts, inaugurated on September 24, 1967, where the established resident theatre, the Dora Wasserman Yiddish Theatre, remains the only permanent Yiddish theatre in North America. The theatre group also tours Canada, US, Israel, and Europe. Bernard Spolsky, author of The Languages of the Jews: A Sociolinguistic History, stated that Yiddish "Yiddish was the dominant language of the Jewish community of Montreal".[71] In 1931 99% of Montreal Jews stated that Yiddish was their mother language. In the 1930s there was a Yiddish language education system and a Yiddish newspaper in Montreal.[71] In 1938, most Jewish households in Montreal primarily used English and often used French and Yiddish. 9% of the Jewish households only used French and 6% only used Yiddish.[72]

Museums and monuments

Canada has several Jewish museums and monuments, which focus upon Jewish culture and Jewish history. They often seek to explore and share the Jewish experience in a given geographical area.

Socioeconomics

Education

There are about a dozen day schools in Toronto and Montreal, as well as a number of Yeshivot. In Toronto, around 40% of Jewish children attend Jewish elementary schools and 12% go to Jewish high schools. The figures for Montreal are higher: 60% and 30%, respectively. There are also a few Jewish day schools in the smaller communities. The national average for attendance at Jewish elementary schools (at least) is 55%.[74]

The Jewish community in Canada is amongst the country's most educated groups. As a group, Canadian Jews tend to be better educated and earn more than most Canadians as a whole. Jews have attained high levels of education, increasingly work in higher class managerial and professional occupations and derive higher incomes than the general Canadian population.[75][76]

Three in ten Jews held managerial and professional positions in 1991, compared to one in five Canadians. In Toronto, four out of ten doctors and dentists were Jewish in 1991 and, nationally, four times as many Jews completed graduate degrees as Canadians generally. The levels of educational attainment among Canadian Jews is dramatically higher than for the overall Canadian population. One out of every two Jews in Canada age fifteen and over was either enrolled in university or had completed a BA in 1991. This is in contrast to Canadians as a whole, among whom one in five was attending university or had completed an undergraduate degree. At the graduate level, these differential rates of education are even higher. About one in six Jews (16 per cent) had obtained an MA, M.D., or PhD in 1991. Among Canadians in general, only one in twenty-five (4 per cent) had attained comparable educational levels.[76][77]

Higher rates of educational achievement are particularly pronounced with Canadian Jews in the thirty-five to forty-four age cohort. Nearly one in four Canadians was enrolled in university or had completed a bachelor's degree in 1991 but among Canadian Jews in this age range, two out of three had comparable levels of education.[75][76]

According to Multicultural Canada, 43 percent of Jewish Canadians have a bachelor's degree or higher; the comparable figure for persons of British origin is 19 percent and compared with just 16 percent of the general Canadian population as a whole.[75][76]

Despite comprising a mere one percent of the Canadian population, Jewish Canadians make up a significant percentage of graduates of some of the most prestigious universities in Canada.[73]

| Rank | University | Enrolment for Jewish Students (2006 est.)[78] | % of Student body | Undergraduate Enrolment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | University of Toronto | 3,000 | 5% | 60,500 |

| 2 | McGill University | 3,500 | 10% | 35,000 |

| 3 | Queen's University | 700 | 7% | 10,350 |

| 4 | University of British Columbia | 800 | 3% | 27,276 |

| 5 | University of Victoria Ryerson University University of Ottawa Carleton University | 700 1,500 650 850 | 4% 7% 2% 4% | 17,000 22,200 32,630 21,732 |

| 6 | University of Waterloo McMaster University Concordia University | 400 500 900 | 2% 3% 3% | 26,854 22,000 33,571 |

| 8 | Simon Fraser University | 400 | 2% | 16,800 |

| 9 | University of Western Ontario | 3,000 | 10% | 30,000 |

| 10 | York University | 4,600 | 10% | 47,000 |

Employment

Before the mass Jewish immigration of the 1880s, the Canadian Jewish community was relatively affluent compared to other ethnic groups in Canada, a distinguishable feature that still continues on to this day. Arguably, Canadian Jews have made a disproportionate contribution to the economic development of Canada throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. During the 18th and the 19th centuries, upper class Jews tended to be fur traders, merchants, and entrepreneurs. In addition, upper middle class white collar occupations also included bankers, lawyers, and doctors as there was an overwhelmingly definable British economic or corporate elite in Canada, Jews remained well represented.[79]

Building a distinctive occupational profile and an affinity for entrepreneurship and business, Jews were heavily involved in the Canadian garment industry as it was the only business for which they had any training. Furthermore, cultural factors that made the industry somewhat lucrative as Jews could be certain that they would not have to work on the Sabbath or on major holidays if they had Jewish employers as opposed to non Jewish employers and were certain that they were also unlikely to encounter anti-Semitism from co-workers. Jews generally did not exhibit any loyalty and sympathy toward the working class through successive generations. Even within the working class, Canadian Jews tended to be concentrated in the ranks of highly skilled, as opposed to unskilled labor. By the end of World War II, Jews in Canada began to disperse in to the working class in large numbers and attained a disproportionate amount success in a variety of white collar jobs and are cited as opening many new business to help stimulate the Canadian economy.

Sol Encel and Leslie Stein, authors of Continuity, Commitment, and Survival: Jewish communities in the diaspora cite that Jews over the age of the 15 who are in University or completed a bachelor's degree is roughly 40% in Montreal, 50% in Toronto and 57% in Vancouver. Stein also cites that Canadian Jews are statistically over-represented in many fields such as medicine, law, finance careers such as banking and accounting, and human service occupations such as social work and academia.[80]

The Winter 1986 - Winter 1987 Issue of Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship cited that despite Jews comprise roughly 1 percent of the Canadian population, they comprised 35% of all entrepreneurs in Quebec and 10% of all technical entrepreneurs in Canada.[81] According to the 1986 census data, about 56 percent of Jewish males, compared to 43 percent among those of British origin, are in select white-collar occupations, such as managerial and administrative positions, the natural sciences, engineering, mathematics, the social sciences, education, medicine and health, the arts, and recreational occupations.[79]

Economics

By any criterion, Canadian Jews have achieved an amount of socioeconomic success that is generally higher compared to the rest of the Canadian population.

Immigrant Jewish males earn $7,000 a year above the Canadian average, higher than any other ethnic and religious group in Canada. Among females, 47 percent are in select white-collar occupations. Immigrant Jewish women earn $3,200 above the national average for women, also the highest for any ethnic group.[79] In modern times, Jews can be numbered among the wealthiest Canadians as they comprise 4% of the Canadian upper class elite despite constituting 1% of the population.[82] Canadian Jews have begun slowly to penetrate those economic sectors that have hitherto been closed to them, concurrently as they are building up wealth in family-owned firms and creating their own family foundations. Prominent Canadian Jewish families such as the Bronfmans, the Belzbergs, and the Reichmanns represent the summit of the extremely affluent segment of high class Jewish society in Canada.[79] Sol Encel and Leslie Stein, authors of Continuity, Commitment, and Survival: Jewish communities in the diaspora write that 22% of Canadian Jews lived in households with an income over $100,000 CAD or more, which was equivalent to the percentage of households in the general population according to StatsCan but was 7.3% higher than Canadian national average according to a University of Alberta study.[83][84] Professional occupations translate into higher incomes for Jews and 38% of Jewish families live in households with an annual income of $75,000 CAD or more.[85][86]

Mark Avrum Ehrlich of The Encyclopedia of the Jewish diaspora: origins, experiences, and culture writes that as Jews find themselves in Canada's contemporary wealthy elite, as 20 percent of the wealthiest Canadians were listed as Jewish.[87] In 2004, Nadav ʻAner, author of The Jewish People Policy Planning Institute cited that Canadian Jews are better educated and more financially off than the general population and have high political influences in the Canadian parliament. Jews are twice as likely as non-Jews to get a bachelor's degree and are three times as likely in the aged 25–34 cohort. This translates into a higher standard of living and they are financially better off than overall Canadian population. Canadian Jews are also three times as likely to earn over $75,000 compared to their non-Jewish counterparts.[88]

The 2011 Forbes' list of billionaires in the world listed 24 Canadian billionaires. Among the billionaires listed, 6 out of the 24 or 25% of the Canadian billionaires listed are Jewish (25 times the percentage of Jews in the Canadian population).[88][89] Sol Encel and Leslie Stein, authors of Continuity, Commitment, and Survival: Jewish communities in the diaspora cite 14% of the top 50 richest Canadians are Jewish (14 times the percentage) as have been 31% of Canada's thirty wealthiest families (31 times the percentage), and while constituting only 1.0 percent of the Canadian population, they comprise 8% of the top executives of Canada's most largest and profitable companies.[80]

Antisemitism

Antisemitism in Canada is the manifestation of hostility, prejudice or discrimination against the Canadian Jewish people or Judaism as a religious, ethnic or racial group. This form of racism has affected Jews since Canada's Jewish community was established in the 18th century.[90][91]

See also

References

- DellaPergola, Sergio (2013). Dashefsky, Arnold; Sheskin, Ira (eds.). "World Jewish Population, 2013" (pdf). Current Jewish Population Reports. Storrs, Connecticut: North American Jewish Data Bank.

- Shahar, Charles (2011). "The Jewish Population of Canada – 2011 National Household Survey". Berman Jewish Databank. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- "Basic Demographics of the Canadian Jewish Community". The Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs. 2011. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- "Jewish Population of the World". Jewish Virtual Library. 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- "JEWISH POPULATION IN THE WORLD AND IN ISRAEL" (PDF). CBS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2011-11-22. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Canadian Jewish Experience". Jcpa.org. 1975-10-16. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables: Religion". Statistics Canada. 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables: Ethnic Origin". Statistics Canada. 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- Sheldon Godfrey and Judy Godfrey. Search Out the Land" The Jews and the Growth of Equality in British Colonial America, 1740–1867. McGill Queen's University Press. 1997. pp. 76–77;Bell, Winthrop Pickard. The "Foreign Protestants" and the Settlement of Nova Scotia:The History of a piece of arrested British Colonial Policy in the Eighteenth Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1961

- Brandeau, Esther Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- Canada's Jews: A Social and Economic Study of Jews in Canada in the 1930s. Louis Rosenberg, Morton Weinfeld. 1993.

- Reporter, Janice Arnold, Staff (28 May 2008). "Exhibition celebrates history of Quebec City Jews – The Canadian Jewish News". Cjnews.com. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- Canada's Entrepreneurs: From The Fur Trade to the 1929 Stock Market Crash: Portraits from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. By Andrew Ross and Andrew Smith, 2012

- Search Out the Land: The Jews and the Growth of Equality in British Colonial America, 1740–1867. Sheldon Godfrey, 1995

- Denis Vaugeois, "Hart, Ezekiel", in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003, accessed June 9, 2013, online

- "The Jewish Community of Montreal". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Hinshelwood, N.M. (1903). Montreal and Vicinity: being a history of the old town, a pictorial record of the modern city, its sports and pastimes, and an illustrated description of many charming summer resorts around. Canada: Desbarats & co. by commission of the City of Montreal and the Department of Agriculture. p. 55. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-08-27. Retrieved 2006-09-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Kitchener Public Library

- Schoenfeld, Stuart. "Jewish Canadians". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Isidore Singer; Cyrus Adler (1907). The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Funk & Wagnalls. p. 286.

- Singer and Adler (1907). The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Funk & Wagnalls. p. 286.

- Hinshelwood, N.M. (1903). Montreal and Vicinity: being a history of the old town, a pictorial record of the modern city, its sports and pastimes, and an illustrated description of many charming summer resorts around. Canada: Desbarats & co. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-226-49407-4. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- "Canada's first Jewish mayor dies suddenly". The Ottawa Citizen. 121st Year (403): 15. 1 February 1964.

- "Ida Siegel with Edmund Scheuer at the Canadian Jewish Farm School, Georgetown". Ontario Jewish Archives. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- BITONTI, DANIEL (9 August 2013). "Remembering Toronto's Christie Pits Riot". Theglobeandmail.com. Retrieved 18 August 2017 – via The Globe and Mail.

- "1: Yiddish culture in Western Canada" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- Goldsborough, Gordon. "MHS Transactions: The Contribution of the Jews to the Opening and Development of the West". Mhs.mb.ca. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- "Story of Saskatchewan's Jewish farmers goes to national museum". CBC News. 12 July 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- Smith, p.123

- Schoenfeld, Stuart (2012-12-03). "Jewish Canadians". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- Waller, Harold. "Montreal, Canada". Jewish Virtual Library. Encyclopedia Judacia. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Curtis, Christopher. "The Bronfman Family". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Beswick, Aaron (2013-12-15). "Canada turned away Jewish refugees". Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- Knowles, Valerie Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540–2006, Toronto: Dundun Press, 2007 page 149.

- Ester Reiter and Roz Usiskin, "Jewish Dissent in Canada: The United Jewish People's Order", paper presented on May 30, 2004 at a forum on "Jewish Dissent in Canada", at a conference of the Association of Canadian Jewish Studies (ACJS) in Winnipeg.

- Benazon, Michael (2004-05-30). "Forum on Jewish Dissent". Vcn.bc.ca. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- Franklin Bialystok, Delayed Impact: The Holocaust and the Canadian Jewish Community (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2000) pp 7–8

- Menkis, Richard. "Abraham L. Feinberg". Jewish Virtual Encyclopedia. Encyclopaedia Judaica. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Sangster, Dorothy (1 October 1950). "The Impulsive Crusader of Holy Blossom". MacLean's. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Feinberg, Abraham (1 March 1945). ""Those Jews" We fight Hitler's creed overseas ... but we have a seedling of it right here at home, says this Rabbi". MacLean's. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Girard, Philip Bora Laskin: Bringing Law to Life, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015 page 251

- Girard, Philip Bora Laskin: Bringing Law to Life, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015 page 251

- Levine, Allan Seeking the Fabled City: The Canadian Jewish Experience, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2018 p.219

- Levine, Allan Seeking the Fabled City: The Canadian Jewish Experience, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2018 p.219

- Levine, Allan Seeking the Fabled City: The Canadian Jewish Experience, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2018 p.219

- Smith, p. 215

- Smith, p. 216

- Smith, p. 218

- Canadian Jewish News (2 September 2014). "Archive collects stories of Southern African Jews". Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Louis Rasminsky". Jewish Virtual Encyclopedia. Encyclopaedia Judaica. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Littman, Sol Pure Soldiers Or Sinister Legion: The Ukrainian 14th Waffen-SS Division, Montreal: Black Rose, 2003 p.180

- Littman, Sol Pure Soldiers Or Sinister Legion: The Ukrainian 14th Waffen-SS Division, Montreal: Black Rose, 2003 p.180

- Pugliese, David (17 May 2018). "Canadian government comes to the defence of Nazi SS and Nazi collaborators but why?". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Tugend, Tom (7 February 1997). "Canada admits letting in 2,000 Ukrainian SS troopers". Jewish News of Northern California. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Meland, Matthew (2016-06-10). "Why do Montreal Jews speak English?". National Observatory on Language Rights. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- "Jewish Life in Greater Montreal Study". Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- "Statistics canada: 2001 Community Profiles". 2.statcan.ca. 2002-03-12. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- "Microsoft Word - Canada_Part1General Demographics_Report.doc" (PDF). Jfgv.org. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- "CanadianParliamentaryCoalitiontoCombatAntisemitism". Cpcca.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- "Report on the Demographic Situation in Canada (Catalogue no. 91-209-XIE)" (PDF). Statistics Canada. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- McQueen, Cynthia (12 August 2013). "Anti-Semitic vandalism in motion across GTA". Theglobeandmail.coom. Retrieved 18 August 2017 – via The Globe and Mail.

- "Antisemitism In Canada: Swastikas In Winnipeg". Jewsnews.co.il. 14 August 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- Reporter, Sheri Shefa, Staff (2 March 2015). "Sephardi delegation heads to Ottawa, meets PM – The Canadian Jewish News". Cjnews.com. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- "The destination of French Jews, Canada". I24news.fr. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- The Canadian Jewish News. "Will Jews flee Belgium and France for Quebec?". Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- The Jewish Agency for Israel. "The Jewish Community of Canada: A History of the Canadian Jewish Community". Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- http://www.jewishdatabank.org/Studies/downloadFile.cfm?FileID=3131

- https://www.jewishdatabank.org/content/upload/bjdb/409/I-CanadaNational-2001-Jewish_Populations_in_Geographic_Areas.pdf

- www.jewishdatabank.org https://www.jewishdatabank.org/databank/search-results/study/743. Retrieved 2019-06-29. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - CHRISTOPHER DEWOLF, "A peek inside Yiddish Montreal", Spacing Montreal, February 23, 2008.

- Spolsky, Bernard. The Languages of the Jews: A Sociolinguistic History. Cambridge University Press, March 27, 2014. ISBN 1139917145, 9781139917148. p. 227.

- Spolsky, Bernard. The Languages of the Jews: A Sociolinguistic History. Cambridge University Press, March 27, 2014. ISBN 1139917145, 9781139917148. p. 226.

- "Carleton University – Hillel: The Foundation for Jewish Campus Life". Hillel. 2008-01-08. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- "Jews of Canada". Jafi.org.il. 2008-12-02. Archived from the original on 2012-05-08. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- "From Immigration To Integration – Chapter Sixteen". Bnaibrith.ca. Archived from the original on 2012-03-30. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- "The Institute for International Affairs Page". Bnaibrith.ca. Archived from the original on 2012-03-30. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- "Religious Discrimination in Canada" (PowerPoint). Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Hillel's Top 10 Jewish Schools Archived December 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Economic Life | Multicultural Canada". Multiculturalcanada.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-08-13. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- Weinfeld, Morton (2003). Continuity, commitment, and survival ... – Sol Encel, Leslie Stein. ISBN 9780275973377. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- Journal of Small Business and ... Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- Wallace Clement. "Elites". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- "2006 Income by Age of Head of Household". Tetrad. Sociology. 2006. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Veenstra, Gerry (2010). Culture and Class in Canada. University of Alberta: Canadian Journal of Sociology.

- Weinfeld, Morton (2003). Continuity, commitment, and survival ... – Sol Encel, Leslie Stein. ISBN 9780275973377. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- Kolber, Leo; Ian Macdonald, L. (2003-10-27). Leo: a life – Leo Kolber, L. Ian MacDonald. ISBN 9780773526341. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- Avrum Ehrlich, M. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Jewish diaspora ... – Mark Avrum Ehrlich. ISBN 9781851098736. Retrieved 2011-12-02.

- income Canadian Jews&f=false. 2005. ISBN 9789652293466. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- "6 Canadian Jews on Forbes' Rich List". Shalom Life. Archived from the original on 2011-09-16. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- Manuel Prutschi, "Anti-Semitism in Canada", Fall 2004. Accessed March 29, 2008.

- Dr. Karen Mock, "Hate Propaganda and Anti-Semitism: Canadian Realities" Archived 2008-08-27 at the Wayback Machine, April 9, 1996. Accessed March 29, 2008.

Notes

- ^ Data based on a study by Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI).

- ^ Data based on a study by Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI).

Bibliography

- Brown, Michael. Jew or Juif? Jews, French Canadians, and Anglo-Canadians, 1759–1914 Jewish Publication Society, 1987

- Brym, Robert J., William Shaffir, and Morton Weinfeld. The Jews in Canada (1993)

- Davies, Alan T. Antisemitism in Canada : history and interpretation, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, (1992)

- Goldberg, David Howard. Foreign Policy and Ethnic Interest Groups: American and Canadian Jews Lobby for Israel (1990)

- Greenstein, Michael ed. Contemporary Jewish Writing in Canada: An Anthology (2004). 233 pp. Primary sources

- Greenstein, Michael. "How They Write Us: Accepting and Excepting 'the Jew' in Canadian Fiction," Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, Volume 20, Number 2, Winter 2002, pp. 5–27 looks at non-Jewish authors.

- Jedwab, Jack. Canadian Jews in the 21st Century: Identity and Demography (2010)

- Lipinsky, Jack. Imposing Their Will: An Organizational History of Jewish Toronto, 1933–1948 (McGill-Queen's University Press; 2011) 352 pages

- Martz, Fraidi. Open Your Hearts: The Story of the Jewish War Orphans in Canada (Montreal: Véhicule Press, 1996. 189 pp.)

- Rosenberg, Louis, and Morton Weinfeld. Canada's Jews: A Social and Economic Study of Jews in Canada in the 1930s (1939; reprinted 1993)

- Singer, Isidore; Cyrus Adler (1907). The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Funk & Wagnalls.

- Srebrnik, Henry. Creating the Chupah: The Zionist Movement and the Drive for Jewish Communal Unity in Canada, 1898–1921 (2011)

- Srebrnik, Henry. Jerusalem on the Amur: Birobidzhan and the Canadian Jewish Communist Movement, 1924–1951 (2008)

- Troper, Harold. The Defining Decade: Identity, Politics, and the Canadian Jewish Community in the 1960s (2010)

- Tulchinsky, Gerald J. J. Canada's Jews: A People's Journey (2008), the standard scholarly history

- Weinfeld, Morton. "Jews" in Paul Robert Magocsi, ed. Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples (1991), pp 860–81, the basic starting point.

- Weinfeld, Morton. W. Shaffir, and I. Cotler, eds. The Canadian Jewish Mosaic (1981), sociological studies

Primary sources

- Jacques J. Lyons and Abraham de Sola, Jewish Calendar with Introductory Essay, Montreal, 1854

- Le Bas Canada, Quebec, 1857

- People of Lower Canada, 1860

- The Star (Montreal), December 30, 1893.

Further reading

- Abella, Irving. A Coat of Many Colours. Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1990.

- Godfrey, Sheldon and Godfrey, Judith. Search Out the Land. Montreal: McGill University Press, 1995.

- Jedwab, Jack. Canadian Jews in the 21st Century: Identity and Demography (2010)

- Leonoff, Cyril. Pioneers, Pedlars and Prayer Shawls: the Jewish Communities in BC and the Yukon. 1978.

- Smith, Cameron (1989). Unfinished Journey: the Lewis Family. Toronto: Summerhill Press. ISBN 0-929091-04-3.

- Schreiber. Canada. The Shengold Jewish Encyclopedia Rockland, Md.: 2001. ISBN 1-887563-66-0.

- Tulchinsky, Gerald. Taking Root. Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1992.

- Jewish Agency Report on Canada

![]()