Judeo-Berber language

Judeo-Berber (Berber languages: ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵜ ⵏ ⵡⵓⴷⴰⵢⵏ tamazight n wudayn, Hebrew: ברברית יהודית berberit yehudit) is any of several hybrid Berber varieties traditionally spoken as a second language in Berber Jewish communities of central and southern Morocco, and perhaps earlier in Algeria. Judeo-Berber is (or was) a contact language; the first language of speakers was Judeo-Arabic.[1] (There were also Jews who spoke Berber as their first language, but not a distinct Jewish variety.)[1] Speakers emigrated to Israel in the 1950s and 1960s. While mutually comprehensible with the Tamazight spoken by most inhabitants of the area (Galand-Pernet et al. 1970:14), these varieties are distinguished by the use of Hebrew loanwords and the pronunciation of š as s (as in many Jewish Moroccan Arabic dialects).

| Judeo-Berber | |

|---|---|

| Region | Israel |

Native speakers | (none[1] L2 speakers: 2,000 cited 1992)[2] |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

| Hebrew alphabet (generally not written) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | jbe |

| Glottolog | (insufficiently attested or not a distinct language)jude1262[3] |

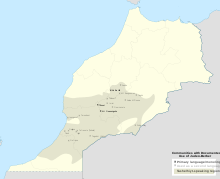

Map of Judeo Berber speaking communities in the first half of the 20th century | |

Speaker population

According to a 1936 survey, approximately 145,700 of Morocco's 161,000 Jews spoke a variety of Berber, 25,000 of whom were reportedly monolingual in the language.[4]

Geographic distribution

Communities where Jews in Morocco spoke Judeo-Berber included : Tinerhir, Ouijjane, Asaka, Imini, Draa valley, Demnate and Ait Bou Oulli in the Tamazight-speaking Middle Atlas and High Atlas and Oufrane, Tiznit and Illigh in the Tasheliyt-speaking Souss valley (Galand-Pernet et al. 1970:2). Jews were living among tribal Berbers, often in the same villages and practiced old tribal Berber protection relationships.

Almost all speakers of Judeo-Berber left Morocco in the years following its independence, and their children have mainly grown up speaking other languages. In 1992, about 2,000 speakers remained, mainly in Israel; all are at least bilingual in Judeo-Arabic.

Phonology

Judeo-Berber is characterized by the following phonetic phenomena: [1]

- Centralized pronunciation of /i u/ as [ɨ ʉ]

- Neutralization of the distinction between /s ʃ/, especially among monolingual speakers

- Delabialization of labialized velars (/kʷ gʷ xʷ ɣʷ/), e.g. nəkkʷni/nukkni > nəkkni 'us, we'

- Insertion of epenthetic [ə] to break up consonant clusters

- Frequent diphthong insertion, as in Judeo-Arabic

- Some varieties have q > kʲ and dˤ > tˤ, as in the local Arabic dialects

- In the eastern Sous Valley region, /l/ > [n] in both Judeo-Berber and Arabic

Usage

Apart from its daily use, Judeo-Berber was used for orally explaining religious texts, and only occasionally written, using Hebrew characters; a manuscript Pesah Haggadah written in Judeo-Berber has been reprinted (Galand-Pernet et al. 1970.) A few prayers, like the Benedictions over the Torah, were recited in Berber.[5]

Example

Taken from Galand-Pernet et al. 1970:121 (itself from a manuscript from Tinghir):

- יִכְדַמְן אַיְיִנַגָא יפּרעו גְמַצָר. יִשוֹפִגַג רבי נּג דְיְנָג שוֹפוֹש נִדְרע שוֹפוֹש יִכיווֹאַנ

- ixəddamn ay n-ga i pərʿu g° maṣər. i-ss-ufġ aġ əṛbbi ənnəġ dinnaġ s ufus ən ddrʿ, s ufus ikuwan.

- Rough word-for-word translation: servants what we-were for Pharaoh in Egypt. he-cause-leave us God our there with arm of might, with arm strong.

- Servants of Pharaoh is what we were in Egypt. Our God brought us out thence with a mighty arm, with a strong arm.

See also

- Judeo-Arabic languages

- Judeo-Moroccan

- Berber Jews

References

- Chetrit (2016) "Jewish Berber", in Kahn & Rubin (eds.) Handbook of Jewish Languages, Brill

- Judeo-Berber at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Judeo-Berber". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Abramson, Glenda (2018-10-24). Sites of Jewish Memory: Jews in and From Islamic Lands. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-75160-1.

- "Jews and Berbers" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-19. (72.8 KB)

Bibliography

- P. Galand-Pernet & Haim Zafrani. Une version berbère de la Haggadah de Pesaḥ: Texte de Tinrhir du Todrha (Maroc). Compres rendus du G.L.E.C.S. Supplement I. 1970. (in French)

- Joseph Chetrit. "Jewish Berber," Handbook of Jewish Languages, ed. Lily Kahn & Aaron D. Rubin. Leiden: Brill. 2016. Pages 118-129.

External links

- Judeo-Berber, by Haim Zafrani (in French)

- Except from Haggadah