Targum

The targumim (singular targum, Hebrew: תרגום; interpretation, translation, version) were originally spoken translations of the Jewish scriptures (also called the Tanakh) that a meturgeman (professional interpreter) would give in the common language of the listeners when that was not Hebrew. This had become necessary near the end of the 1st century BCE, as the common language was Aramaic and Hebrew was used for little more than schooling and worship.[1] The meturgeman frequently expanded his translation with paraphrases, explanations and examples so that it became a kind of sermon.

Writing down the targum was initially prohibited; nevertheless, some targumatic writings appeared as early as the middle of the first century CE.[1] They were not then recognized as authoritative by the religious leaders.[1] Some subsequent Jewish traditions (beginning with the Babylonian Jews) accepted the written targumim as authoritative translation of the Hebrew scriptures into Aramaic. Today, the common meaning of "targum" is a written Aramaic translation of the Bible. Only Yemenite Jews continue to use the targumim liturgically.

As translations, the targumim largely reflect midrashic interpretation of the Tanakh from the time they were written and are notable for favoring allegorical readings over anthropomorphisms.[2] (Maimonides, for one, notes this often in The Guide for the Perplexed.) That is true both for those targumim that are fairly literal as well as for those that contain many midrashic expansions. In 1541, Elia Levita wrote and published Sefer Meturgeman, explaining all the Aramaic words found in the Targum.[3][4]

Targumim are used today as sources in text-critical editions of the Bible (BHS refers to them with the abbreviation 𝔗).

Etymology

The noun "Targum" is derived from the early semitic quadriliteral root trgm, and the Akkadian term targummanu refers to "translator, interpreter".[5] It occurs in the Hebrew Bible in Ezra 4:7 "... and the writing of the letter was written in Aramaic (aramit) and interpreted (tirgam) into Aramaic." Besides denoting the translations of the Bible, the term Targum also denote the oral rendering of Bible lections in synagogue,[5] while the translator of the Bible was simply called hammeturgem (he who translates). Other than the meaning "translate" the verb Tirgem also means "to explain".[5] The word Targum refers to "translation" and argumentation or "explanation".[5]

Two major targumim

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Perspectives |

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

The two most important targumim for liturgical purposes are:[6]

- Targum Onkelos on the Torah (Written Law)

- Targum Jonathan on the Nevi'im (Prophets)

These two targumim are mentioned in the Babylonian Talmud as targum dilan ("our Targum"), giving them official status. In the synagogues of talmudic times, Targum Onkelos was read alternately with the Torah, verse by verse, and Targum Jonathan was read alternately with the selection from Nevi'im (i.e., the Haftarah). This custom continues today in Yemenite Jewish synagogues. The Yemenite Jews are the only Jewish community to continue the use of Targum as liturgical text, as well as to preserve a living tradition of pronunciation for the Aramaic of the targumim (according to a Babylonian dialect).

Besides its public function in the synagogue, the Babylonian Talmud also mentions targum in the context of a personal study requirement: "A person should always review his portions of scripture along with the community, reading the scripture twice and the targum once" (Berakhot 8a–b). This too refers to Targum Onkelos on the public Torah reading and to Targum Jonathan on the haftarot from Nevi'im.

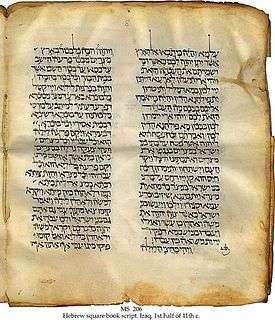

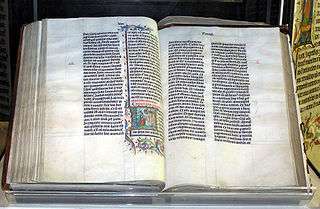

Medieval biblical manuscripts of the Tiberian mesorah sometimes contain the Hebrew text interpolated, verse-by-verse, with the targumim. This scribal practice has its roots both in the public reading of the Targum and in the private study requirement.

The two "official" targumim are considered eastern (Babylonian). Nevertheless, scholars believe they too originated in the Land of Israel because of a strong linguistic substratum of Western Aramaic. Though these targumim were later "orientalised", the substratum belying their origins still remains.

When most Jewish communities had ceased speaking Aramaic, in the 10th century CE, the public reading of Targum along with the Torah and Haftarah was abandoned in most communities, Yemen being a well-known exception.

The private study requirement to review the Targum was never entirely relaxed, even when Jewish communities had largely ceased speaking Aramaic, and the Targum never ceased to be a major source for Jewish exegesis. For instance, it serves as a major source in the Torah commentary of Shlomo Yitzhaki, "Rashi", and has always been the standard fare for Ashkenazi (French, central European, and German) Jews onward.

For these reasons, Jewish editions of the Tanakh which include commentaries still almost always print the Targum alongside the text, in all Jewish communities. Nevertheless, later halakhic authorities argued that the requirement to privately review the targum might also be met by reading a translation in the current vernacular in place of the official Targum, or else by studying an important commentary containing midrashic interpretation (especially that of Rashi).

Targum Ketuvim

The Talmud explicitly states that no official targumim were composed besides these two on Torah and Nevi'im alone, and that there is no official targum to Ketuvim ("The Writings"). The Talmud (Megilah 3a) states The Targum of the Pentateuch was composed by Onkelos the proselyte from the mouths of R. Eleazar and R. Joshua. The Targum of the Prophets was composed by Jonathan ben Uzziel under the guidance of Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi (Jonathan b. Uzziel was a disciple of Hillel, so he had traditions handed down from them-Maharsha), and the land of Israel [thereupon] quaked over an area of four hundred parasangs by four hundred parasangs, and a Bath Kol (heavenly voice) came forth and exclaimed, Who is this that has revealed My secrets to mankind? Jonathan b. Uzziel thereupon arose and said, It is I who have revealed Thy secrets to mankind. It is fully known to Thee that I have not done this for my own honour or for the honour of my father's house, but for Thy honour l have done it, that dissension may not increase in Israel. He further sought to reveal [by] a targum [the inner meaning] of the Hagiographa, but a Bath Kol went forth and said, Enough! What was the reason? Because the date of the Messiah is foretold in it". [A possible reference to the end of the book of Daniel.] But did Onkelos the proselyte compose the targum to the Pentateuch? Has not R. Ika said, in the name of R. Hananel who had it from Rab: What is meant by the text, Neh. VIII,8 "And they read in the book, in the law of God, with an interpretation. and they gave the sense, and caused them to understand the reading? And they read in the book, in the law of God: this indicates the [Hebrew] text; with an interpretation: this indicates the targum,..." (which shows that the targum dates back to the time of Ezra).

Nevertheless, most books of Ketuvim (with the exceptions of Daniel and Ezra-Nehemiah, which both contain Aramaic portions) have targumim, whose origin is mostly western (Land of Israel) rather than eastern (Babylonia). But for lack of a fixed place in the liturgy, they were poorly preserved and less well known. From Palestine, the tradition of targum to Ketuvim made its way to Italy, and from there to medieval Ashkenaz and Sepharad. The targumim of Psalms, Proverbs, and Job are generally treated as a unit, as are the targumim of the five scrolls (Esther has a longer "Second Targum" as well.) The targum of Chronicles is quite late, possibly medieval, and is attributed to a Rabbi Joseph.

Other Targumim on the Torah

There are also a variety of western targumim on the Torah, each of which was traditionally called Targum Yerushalmi ("Jerusalem Targum"), and written in Western Aramaic. An important one of these was mistakenly labeled "Targum Jonathan" in later printed versions (though all medieval authorities refer to it by its correct name). The error crept in because of an abbreviation: the printer interpreted the abbreviation T Y (ת"י) to stand for Targum Yonathan (תרגום יונתן) instead of the correct Targum Yerushalmi (תרגום ירושלמי). Scholars refer to this targum as Targum Pseudo-Jonathan. To attribute this targum to Jonathan ben Uzziel flatly contradicts the talmudic tradition (Megillah 3a), which quite clearly attributes the targum to Nevi'im alone to him, while stating that there is no official targum to Ketuvim. In the same printed versions, a similar fragment targum is correctly labeled as Targum Yerushalmi.

The Western Targumim on the Torah, or Palestinian Targumim as they are also called, consist of three manuscript groups: Targum Neofiti I, Fragment Targums, and Cairo Geniza Fragment Targums.

Of these Targum Neofiti I is by far the largest. It consist of 450 folios covering all books of the Pentateuch, with only a few damaged verses. The history of the manuscript begins 1587 when the censor Andrea de Monte (d. 1587) bequeathed it to Ugo Boncompagni—which presents an oddity, since Boncompagni, better known as Pope Gregory XIII, died in 1585. The route of transmission may instead be by a certain "Giovan Paolo Eustachio romano neophito."[7] Before this de Monte had censored it by deleting most references to idolatry. In 1602 Boncompagni's estate gave it to the Collegium Ecclesiasticum Adolescentium Neophytorum (or Pia Domus Neophytorum, a college for converts from Judaism and Islam) until 1886, when the Vatican bought it along with other manuscripts when the Collegium closed (which is the reason for the manuscripts name and its designation). Unfortunately, it was then mistitled as a manuscript of Targum Onkelos until 1949, when Alejandro Díez Macho noticed that it differed significantly from Targum Onkelos. It was translated and published during 1968–79, and has since been considered the most important of the Palestinian Targumim, as it is by far the most complete and, apparently, the earliest as well.[8][9]

The Fragment Targums (formerly known as Targum Yerushalmi II) consist of many fragments that have been divided into ten manuscripts. Of these P, V and L were first published in 1899 by M Ginsburger, A, B, C, D, F and G in 1930 by P Kahle and E in 1955 by A Díez Macho. Unfortunately, these manuscripts are all too fragmented to confirm what their purpose were, but they seem to be either the remains of a single complete targum or short variant readings of another targum. As a group, they often share theological views and with Targum Neofiti, which has led to the belief that they could be variant readings of that targum.[8][9]

The Cairo Genizah Fragment Targums originate from the Ben-Ezra Synagogues genizah in Cairo. They share similarities with The Fragment Targums in that they consist of many fragmented manuscripts that have been collected in one targum-group. The manuscripts A and E are the oldest among the Palestinian Targum and have been dated to around the seventh century. Manuscripts C, E, H and Z contain only passages from Genesis, A from Exodus while MS B contain verses from both as well as from Deuteronomium.[8][9]

The Samaritan community has their own Targum to their text of the Torah. Other Targumim were also discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls.[10]

Peshitta

The Peshitta is the traditional Bible of Syriac-speaking Christians (who speak several different dialects of Aramaic). The translation of the Peshitta is usually thought to be between 1 and 300 CE.[11]

See also

References

- Schühlein, Franz (1912). Targum. New York: Robert Appleton.

- Oesterley, WOE; Box, GH (1920). A Short Survey of the Literature of Rabbinical and Mediæval Judaism. New York: Burt Franklin.

- "Levita, Elijah", in the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia.

- Levita, Elijah (17 March 2018). "Sefer meturgeman". Retrieved 17 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- Philip S. Alexander, (1992) "Targum, Targumim," in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday), 6:320–31

- Ellis R. Brotzman; Eric J. Tully (19 July 2016). Old Testament Textual Criticism: A Practical Introduction. Baker Publishing Group. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4934-0475-9.

- Studi di biblioteconomia e storia del libro in onore di Francesco Barberi, ed. Giorgio De Gregori, Maria Valenti – 1976 "(42) Trascrivo una supplica dell'Eustachio al Sirleto : « Giovan Paolo Eustachio romano neophito devotissimo servidor di... (44) « Die 22 mensis augusti 1602. Inventarium factum in domo illustrissimi domini Ugonis Boncompagni posita".

- McNamara, M. (1972) Targum and Testament. Shannon, Irish University Press.

- Sysling, H. (1996) Tehiyyat Ha-Metim. Tübingen, JCB Mohr.

- "The Dead Sea Scrolls - Browse Manuscripts". www.deadseascrolls.org.il. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- For the date of translation, see Peter J. Williams (2001). Studies in the Syntax of the Peshitta of 1 Kings. BRILL. p. 2. ISBN 90-04-11978-7.

Tadmor, H., 1991. "On the role of Aramaic in the Assyrian empire", in M. Mori, H. Ogawa and M. Yoshikawa (eds.), Near Eastern Studies Dedicated to H.I.H. Prince Takahito Mikasa on the Occasion of his Seventy-Fifth Birthday, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 419–426

External links

English translations of Targum

- Ecclesiastes in The Song of Songs and Coheleth, Christian David Ginsburg (1857) pages 503-519.

- Etheridge, John Wesley. "Targum Pseudo-Jonathan and Targum Onkelos". Newsletter for Targumic and Cognate Studies.

- Cook, Edward M. "The Aramaic Targum to Psalms". Targum.info. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017.

- Treat, Jay C. "The Aramaic Targum to the Song of Songs (Shir HaShirim)". University of Pennsylvania.

- Levey, Samson H. "The Aramaic Targum to Ruth". Targum.info.

- Brady, Christian 'Chris' MM. "Targum Ruth in English". Targuman.

- ————————. "The Aramaic Targum to Lamentations". Targum.info.

- Aramaic Targums—The Aramaic text of Targum Onkelos and Samaritan Targum with a new English translation for each version and critical apparatus.

Other sources on Targum

- "Targum". The Jewish Encyclopedia.

- "The Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon". HUC.—contains critical editions of all the targumim along with lexical tools and grammatical analysis.

- "Targum". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent.

- Faur, Jose. "The Targumim and Halakha" (article). Derushah., analyzing the status of the Targumim in Jewish law

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.